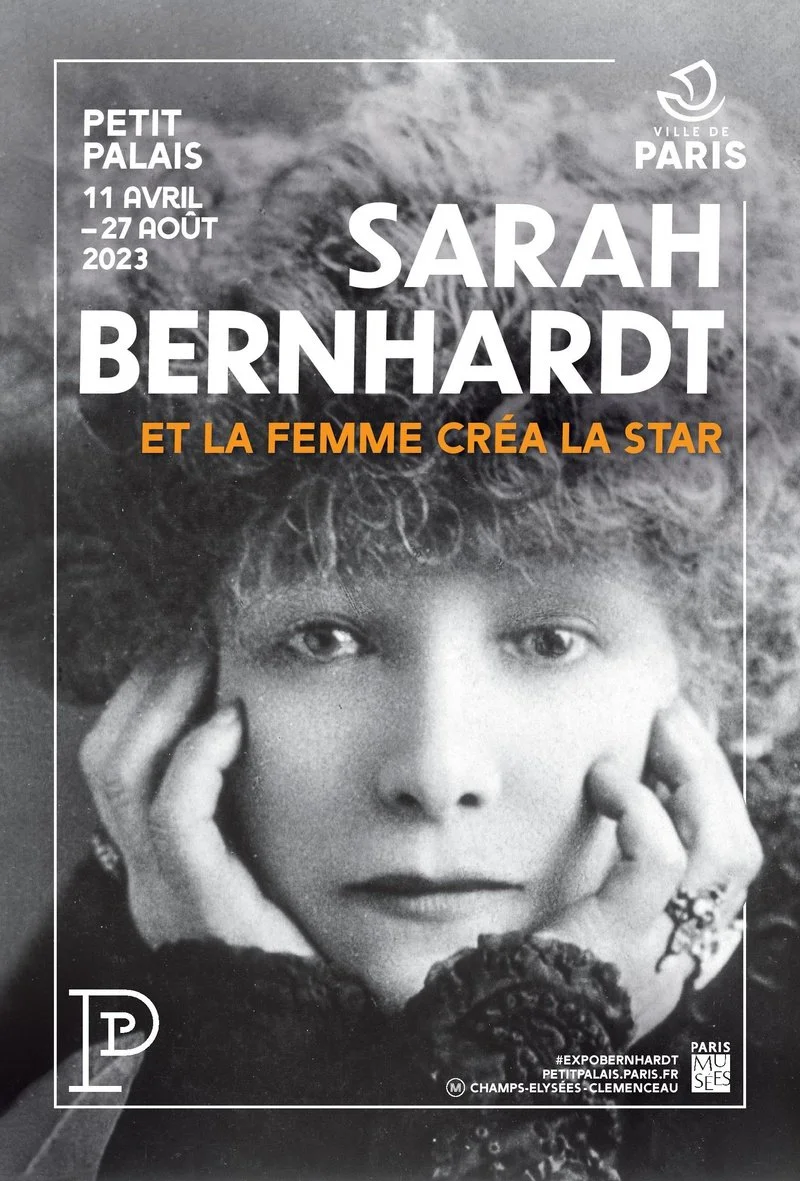

’Et la femme créa la star’

Sarah Bernhardt at the Petit Palais

The exhibition currently at the Petit Palais marks the centennial of Sarah Bernhardt’s death. Everybody has heard of Sarah Bernhardt. And everybody knows something about her. Or thinks they do. For me it used to be that she slept in a coffin. For the past year, it has been that she was the inspiration for Proust’s diva, Berma.

Sarah embellished and modified her biography when she felt like it. Here are a few facts about her early life that are probably true. She was born in 1844 in Paris. Her mother was a Dutch Jewish courtesan with an impressive list of wealthy clients and benefactors. From the beginning she didn’t like Sarah very much and sent her off to a wet-nurse in Brittany. Eventually, with the help of the Duc de Morny, Napoleon III’s half brother, then President of the French legislature and one of Sarah’s mother’s admirers, Sarah was enrolled in a prestigious Catholic convent school just outside of Versailles. Perhaps the expenses were paid with money from her unnamed father.

A few other facts: Sarah had many admirers, took many lovers. Among the latter, the actor Mounet-Sully (much celebrated in his hometown, Bergerac) and the bon vivant and aesthete, Charles Haas, (Proust’s model for the character of Charles Swann), the artist Gustave Doré and the writer, Victor Hugo. Sarah toured America nine times. She traveled to Cairo, Istanbul, Tahiti, Rio de Janeiro, and of course, throughout Europe and England. She became a Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur in 1917. Her funeral procession in 1923 filled the streets of Paris.

As I was doing research on the exhibition at the Petit Palais, I stumbled upon a newspaper article about Bernhardt’s leg, which was amputated in 1915, which had gone missing immediately, which has now been rediscovered. I learned that Robert Gottlieb (Robert Caro’s longtime editor) who died a couple weeks ago at age 92, who read all 7 volumes of Proust in 7 days, wrote a biography of Bernhardt 13 years ago.

Then I read about two other exhibitions. One held at the BNF in 2000, called "Sarah Bernhardt ou le Divin Mensonge," (the Divine Lie). It was, according to Mary Blume, writing for the now defunct International Herald Tribune, held to celebrate the centenary of the date that “Bernhardt first stepped on the stage of her Sarah Bernhardt Theater,” where she went on to produce plays for the next 20 years “in the tightly fitting white (military) uniform, designed by Paul Poiret,” (Figure 1) She played the title role in the play, l’Aiglon, written by Edmond Rostand. Aiglon, (eaglet), was the nickname of Napoleon’s son. Napoleon, of course was the Eagle. “As she expertly expired… the weeping audience rose to cheer, their enthusiasm undimmed by the fact that she was playing a 20-year-old youth at the age of 56.”

Figure 1. Sarah Bernhardt as Aiglon in the play l”Aiglon written by Edmond Rostand (1900)

Sarah experimented with age and gender throughout her career. She played the 19-year-old Joan of Arc when she was 46 and in 1899, at age 56, she played Hamlet (Figure 2) in French before an English audience at Stratford-upon-Avon. In her book L’Art du théâtre (1923), Bernhardt explained why she chose male roles - easy - they were more complex than female ones.

Figure 2. Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet in play Hamlet, Shakespeare (1899)

The exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York, held in in 2006, “Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama” was, like other exhibitions in Paris, (‘Paris for School’ at the MahJ comes to mind) thematically very similar to this Parisian one.

According to Annick Lemoine, director of the Petit Palais, “(Sarah) was the first real star in history; she paved the way for the likes of Greta Garbo, Marilyn Monroe, Madonna and Beyoncé … (S)he was not only a great actress, she was an influencer of fashion, an artist and a sculptor, a writer and an activist….”

Sarah is presented as a multi-faceted person. We learn about her accomplishments as artist and feminist; self promoter and entrepreneur. We learn about her personal life - the sensational aspects and the somber ones. We learn about her physical frailties and her psychological strengths. Portraits of her are scattered throughout the exhibition, as are caricatures, some of which are gently mocking, others of which are simply cruel.

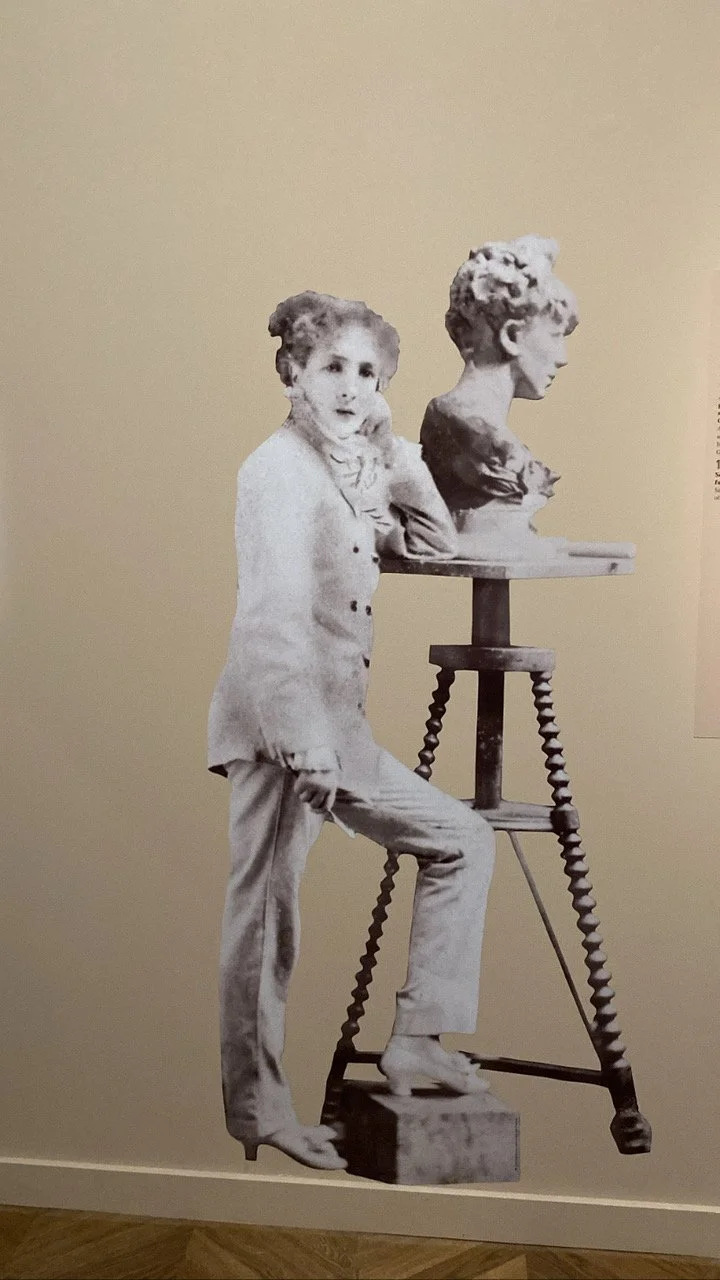

The spaces through which we walk are as varied as the subject for which they were created. You have a sense of moving through stage sets. One room, for example, is given over to her own sculptures and paintings. (Figures 3, 4) Sarah was an accomplished sculptor who exhibited at the Salon, It’s not surprising that Sarah chose an art form normally associated with men. Like choosing to play men in the theatre, sculpture was probably more interesting, more challenging to her. A photograph of her sculpting, shows her wearing a white satin pantsuit designed by the couturier, Charles Worth, known for his elegant creations. (Figure 5)

Figure 3. Sarah Bernhardt exhibition, Petit Palais, sculpture and paintings by and of Sarah Bernhardt

Figure 4. Detail of Figure 3.

Figure 5. Sarah Bernhardt sculpting in an outfit designed by Charles Worth

Her sculptures on display include bust portraits of artist friends, a creepy funerary portrait of her husband with his disembodied head lying on a bed of roses and poppies. And I suppose, not surprisingly there are a few self-portraits.

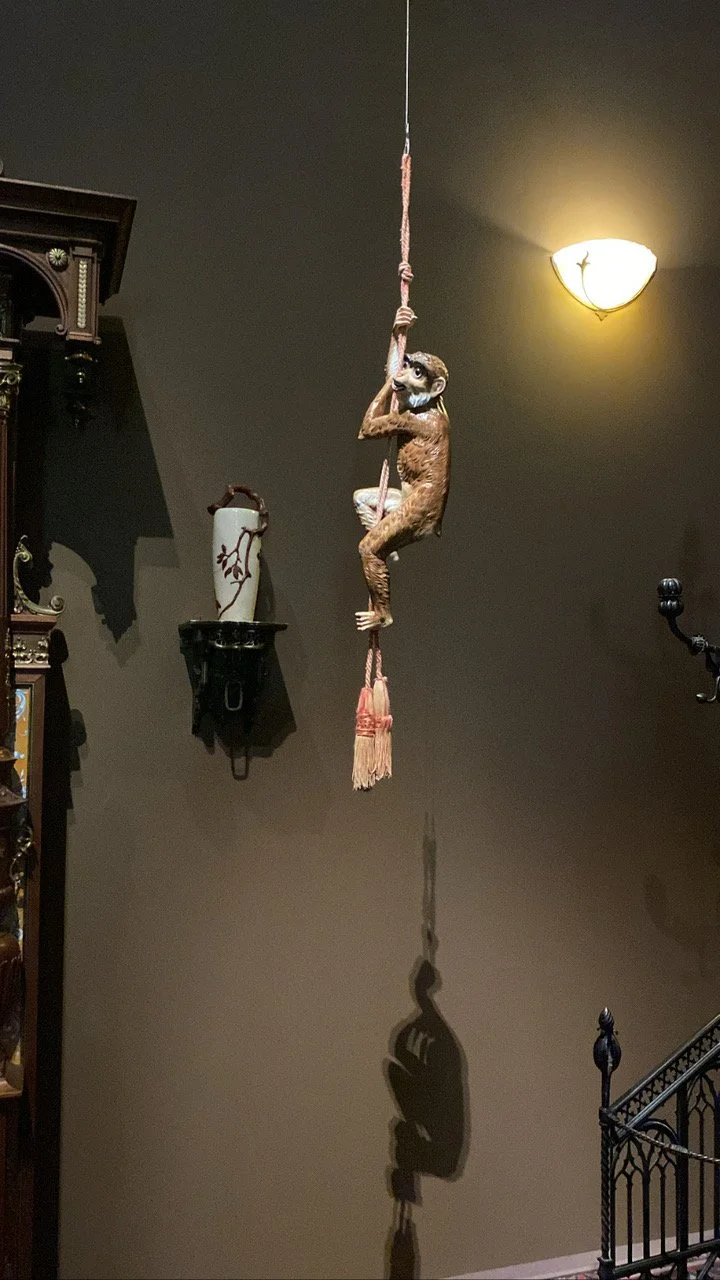

Sarah made art, surrounded herself with art and was as well, a work of art herself. Evidence of all of this here for us to see. Her home was decorated with objets and bibelots (Figures 6, 7). Following Oscar Wilde's injunction to either be a work of art or to wear one, portraits of Sarah show her in sumptuous gowns and elegant accessories, indeed as a "work of art” (Figure 8)

Figure 6. Interior de Sarah Bernhardt’s home

Figure 7. Detail of Figure 6.

Figure 8. Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt by Georges Clarion

In another room, through interactive maps, we learn about her many international trips. Her acting career is near the end of the exhibition. Which was an excellent decision. It is easier to appreciate what is new when we are fresh and to see what is familiar at the end.

In a review of the New York exhibition, Willa Z. Silverman, in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (Autumn 2006), offers perceptive reflections on the themes central to the Paris exhibition, too. About Sarah’s stardom for example, Silverman contends that she was “one of the earliest artists to take advantage of the many new technologies of the late nineteenth century, and the new media they spawned, in order to create her image, and then to control it.”

Photos of her, about, initially taken by the pioneer photographer, Nadar. (Figure 9) Sarah’s rise to stardom was simultaneous with a proliferation of paper - daily newspapers of course. As well as postcards and playbills and posters; sheet music and menus and maps. All of which had to be decorated with something. Many of which were decorated with images of Sarah. It reminded me of what the curator of the exhibition on Kimonos at the V & A said about geishas and actors. They became stars in Japan through the dissemination of inexpensive prints adorned with their faces and costumes.

Figure 9. Portrait photo of Sarah Bernhardt by Nadar, 1864

As Silverman notes, Bernhardt’s face on packages of teas and biscuits and sardines and face powder sold products. They also sold her. (Figure 10)

Figure 10. Sarah Bernhard’s face on Carter's Liver Bitters

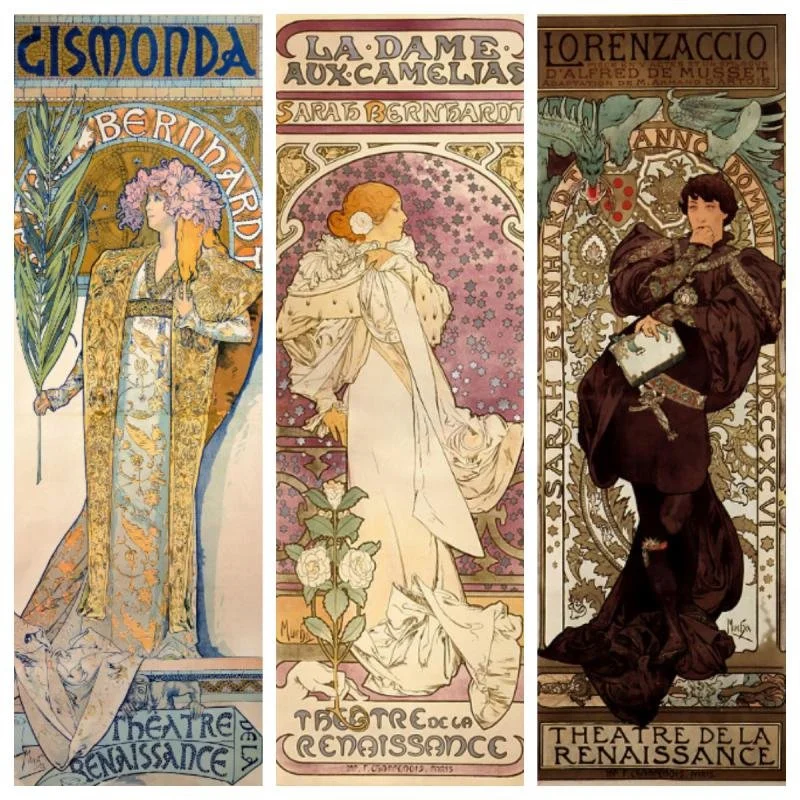

The ‘gallery of great roles’ celebrating Bernhardt’s theatrical performances includes models of theatrical sets, a sampling of the costumes and jewelry she wore when she played Joan of Arc, Cleopatra, Phaedra, the Byzantine Empress Theodora, etc. (Figures 11, 12, 13) And the posters advertising the plays, by the Czech artist, Alphonse Mucha. Mucha arrived in Paris in 1887 and found employment as a graphic designer. His life and luck changed in 1894 when Bernhardt discovered him. Mucha worked under exclusive contract with Sarah for six years. He designed stage sets and costumes as well as posters. They are Art Nouveau beautiful but looking at them altogether, the word repetition springs to mind. In each, the name of the play is at the top, the name of the theatre is at the bottom. A full length portrait of Sarah, holding an object, a book, a dagger, something linked with the character she plays, unites the two. (Figures 14, 15) I haven’t read or seen the plays written for Sarah by Victorien Sardo, but according to Silverman, they all have the same form and plot line. Sounds a lot like Law and Order, doesn’t it?

Figure 11. Sarah Bernhardt as Cleopatra

Figure 12. Sarah’s costume for Jeanne d’Arc

Figure 13. Stage set

Figure 14. Theatre Posters for Sarah Bernhardt performances, Alphonse Mucha

Figure 15. Poster for La Samaritaine, Alphonse Mucha

Sarah was a theater owner, producer, manager and director with complete creative and financial control over the plays she produced. As Silverman notes, normally it would have been impossible for a woman to succeed in the business world, a world controlled by men. But the victory seems less sweet when we realize that “the theater was one business where actress-owners could operate in relative freedom, due to the pariah-like status historically accorded to them.”

Sarah’s Jewishness and Frenchness are explored in the exhibition. Sarah went to Catholic boarding school and considered herself Catholic. But she never denied her Jewish roots. Late 19th century France might have been a time when Jews assimilated and found jobs at the highest level of commerce and academia, but it was also a time of increasing French nationalism. Those two strains were bound to clash. And clash they did with the Dreyfus affair.

Like Proust, Sarah was a Dreyfusard, that is, she believed in the innocence of Alfred Dreyfus, the army captain accused of passing military secrets to the Germans. Despite another officer’s admission of guilt, despite reams of evidence that should have exonerating him, the court refused to overturn his sentence of life imprisonment on Devil’s Island. That is, until Emile Zola published an essay in a newspaper entitled ‘J’accuse’ condemning the military and judicial systems. A letter from Sarah to Zola in support of his stance is at the Petit Palais.

Although some French Jews urged caution, neutrality wasn’t really an option. Members of the same family sometimes took opposing views. As was the case with Proust, his mother (who was born Jewish), his brother and he supported Dreyfus. His father didn’t. Sarah’s son Maurice, like Proust’s father was an anti-Dreyfusard.

Sarah’s very public support of Dreyfus led to a proliferation of anti-semitic caricatures of her. She is depicted like a snake, skinny with frizzy haired and a hook nosed. (Figures 16, 17,18, 19) Caricatures could be ignored but it was a courageous act for a performer and producer whose income depended upon not offending the theatre going public.

Figure 16. Caricature of Sarah Bernhardt

Figure 17. Painting of Sarah Bernhardt upon which figure 16 is based

Figure 18. Caricature of painting of Sarah Bernhardt

Figure 19. Ginevra with the photo upon which #18 caricature is based

` She was Jewish but no one could question Sarah’s patriotism. During the siege of Paris in 1870, she transformed the Odéon Theatre into a “military hospital, filling the dressing rooms, auditorium and stage with cots of injured and dying men and bullying her …. lovers into supplying provisions.…” Decades later, during the first World War, impatient with the pain that restricted her movement, she chose to have her leg amputated so she could tour the front and entertain the troops, albeit in a sedan chair. (Figure 20) The French government acknowledged her dedication to France and she became a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Figure 20. Sarah in a sedan chair to entertain the troops, 11 May 1916

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.