Making the Most of the Moment

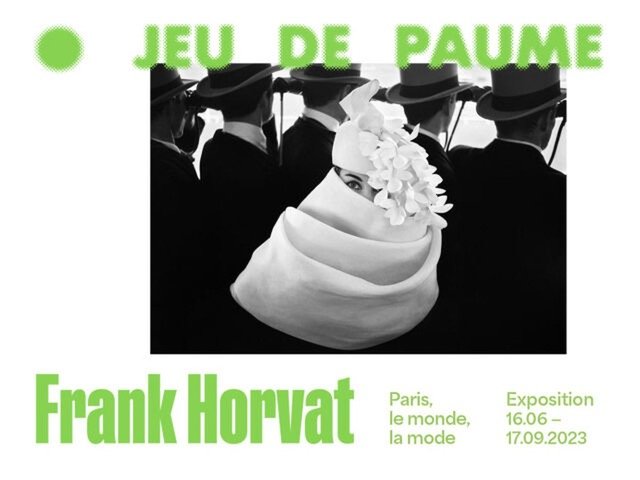

Frank Horvat: Paris, le monde, la mode, Jeu de Paume

“If photojournalism shows things as they are, fashion photography shows them as we would like them to be.” Frank Horvat.

There always seems to be a photography exhibition going on here, in Paris. One of my favorites was on the fashion photography of surrealist artist, Man Ray. Who didn’t like fashion photography. It was a job for him, something he did to pay the bills. He didn’t think it was art. But he pushed the boundaries as far as he could. (Fig. 1)

Figure. 1. Man Ray et la Mode, Musée du Luxembourg

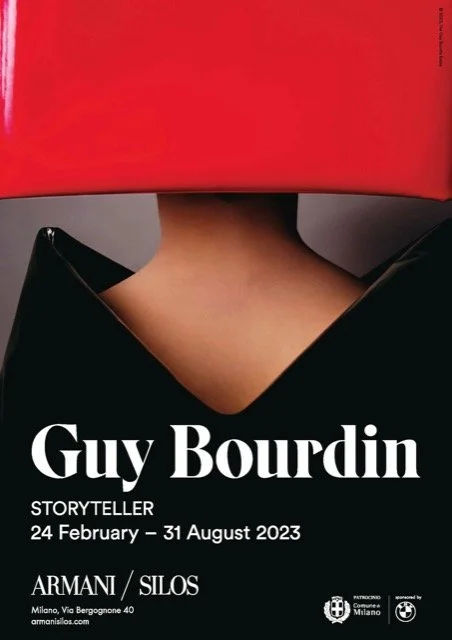

For a while there were exhibitions about fashion photographers, everywhere. Well more precisely about fashion magazines, like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and Vanity Fair which were, of course, filled with photographs taken by photographers like Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Guy Bourdin, Storyteller, Armani/Silos, Milan

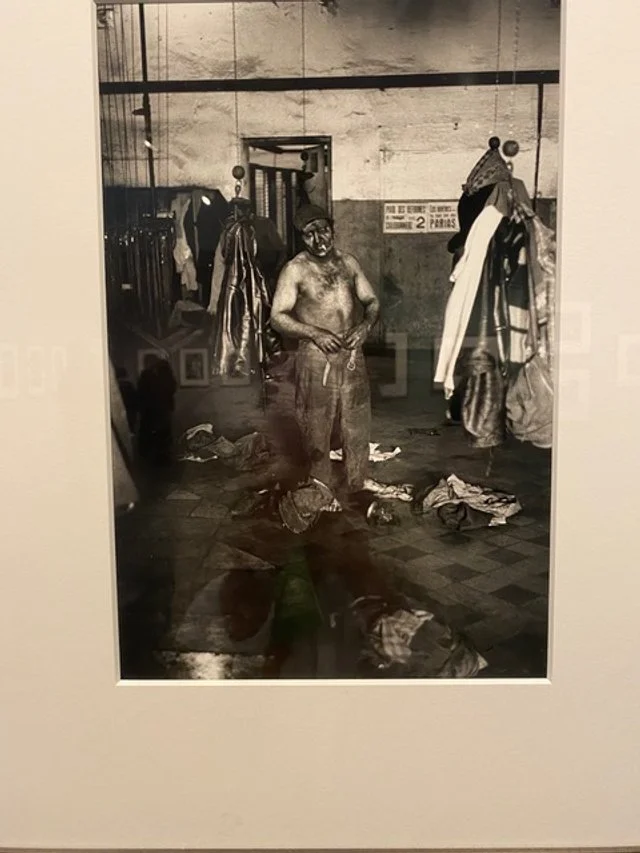

There was also an exhibition about the documentary photographer, Eugène Atget, (Fig. 3) whose photographs of a disappearing Paris at the end of the 19th century were saved from oblivion by the American photographer, Berenice Abbott.

Figure 3. Chiffonier, (Rag Picker) Eugène Atget

Then there were two exhibitions on the photo-journalist Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose ‘Decisive Moment’ (Fig. 4) was both the moment he snapped a photo and his decision in 1947, to start Magnum Photos, a cooperative of photo-journalists, committed to making sure its members retain the copyright to their own work.

Figure 4. Rue Mouffetard, Henri Cartier-Bresson. 1954

There have been quirky exhibitions, too. Like the one about Vivian Maier, who worked as a nanny her whole life, her camera always nearby. She mostly snapped photos of people on the street, people she didn’t know. (Fig. 5) Photographs which no one saw until after her death, when the man who purchased boxes of her work at an auction began opening what he had bought on a whim.

Figure 5. Vivian Maier, Musée du Luxembourg

The Elliott Erwitt exhibition at the Musée Maillol is about a photographer who captures, according to Adam Gopnik, the ‘Delighted Moment’ in both the photos he produced for his clients and those he took for himself, for his art. (Fig 6)

Figure 6. At the museum, Goya’s Majas dressed (left) / undressed (right), Elliott Erwitt

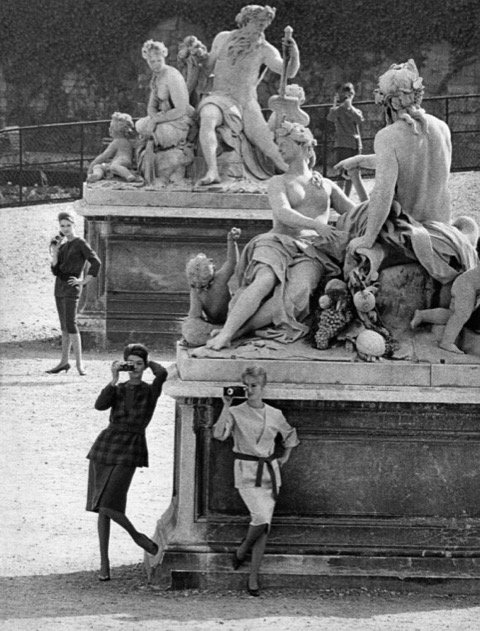

Today, the subject is another photographer, Frank Horvat. (Fig 7) A photo-journalist like Cartier-Bresson, a fashion photographer like Richard Avedon, an eager member of Magnum like Erwitt. And a photographer who died with many of his photographs languishing unseen, like Vivian Maier.

Figure 7. Givenchy hat, Paris, Jardin des Modes, Frank Horvat, 1958

So prolific was Horvat that this exhibition is only about the first 15 years of his career - from 1950 to 1965, from age 22 to 37.

According to the curators of the exhibition, Horvat’s autobiographical writings “tell of an inner journey…of an artist motivated by an ongoing search for new experiences … (from) the history of post-war illustrated press (to) the upheaval of the conventions of fashion photography…” Frank Horvat was born in 1928 in Abbazia, Italy, (now Opatija, Croatia). His father was a pediatrician, his mother was a psychiatrist. As Jews, they fled Italy for Switzerland in 1939 when Franco and the Fascists made living in Italy too dangerous for them.

Horvat bought his first camera in 1943, using money he got from selling his stamp collection. His hope was that it would be a way for a shy guy like him to flirt with girls! In 1947, the family moved back to Italy and Horvat began studying fine art at the Brera Academy of Art in Milan.

He planned to become a painter or a writer but discovered that he enjoyed and was good at telling stories with a camera. Here is what he said when he got to Paris for the first time in 1950. “When I first set foot there, Paris was for me the capital of the world. From that of fashion of course, but also from those of painting, letters, shows and above all – in my perspective – photojournalism, because it was the headquarters of Magnum…”

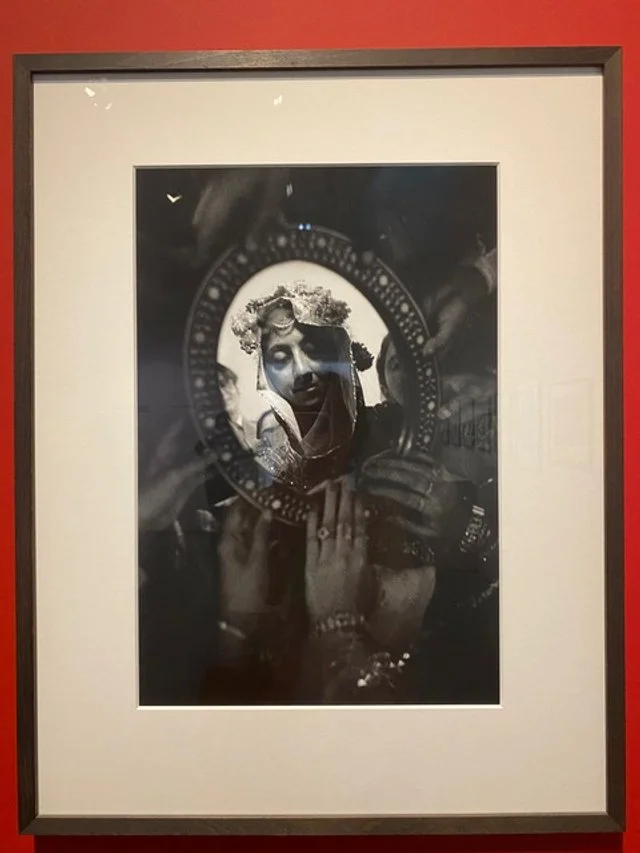

He met his hero, Henri Cartier-Bresson who told him to buy a Leica and travel. He did both. He went to Pakistan and India as a freelance photographer. In Pakistan, his subjects were almost schizophrenic, as they would be for the next 15 years. He would focus at one moment on prostitutes and opium dens (Fig. 8) and at another on centuries-old Muslim traditions.There is his photo of a young woman looking down, into the mirror on her lap. (Fig. 9) She has just removed her veil. With her back to the man she has just married, she lets his gaze fall upon her face in a mirror. It is the first time he is seeing the face of his wife. Horvat was the first Westerner to photograph private scenes like this one. When Alfred Steichen was putting together his 1955 exhibition, ‘The Family of Man,’ for MoMA, this photograph was included.

Figure 8. Red Light District, Lahore, Pakistan, Frank Horvat, 1952

Figure 9. Bride’s Face in Mirror, Pakistan, Frank Horvat, 1952

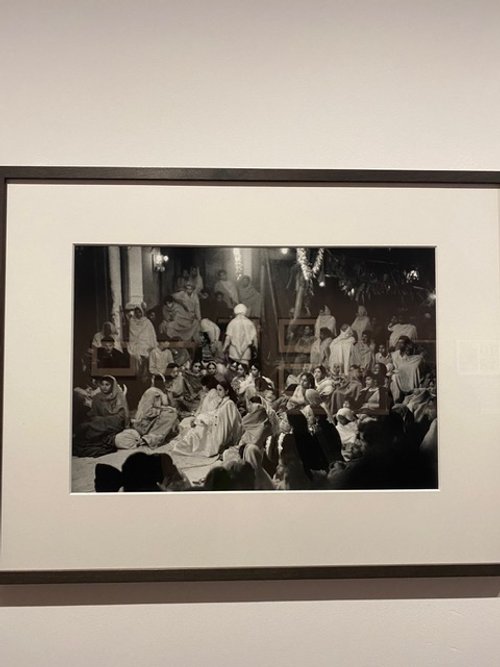

Here’s another, also from Pakistan. An annual celebration held in Lahore’s red-light district. Young women dance, with jewelry, without veils. (Fig. 10) They are exposed to the gaze of men who then bid for the women at auction. The lucky bidder doesn’t own the woman, just the chance to speak with her family - to ask for a meeting or perhaps a marriage. These images graced the cover of the German, Die Woche.

Figure 10. Young woman dancing without veils, Lahore, Pakistan, Frank Horvat, 1953

In 1954, after a couple years in South Asia, Horvat moved to London for a year. His photographs are amusing and ironic. (Fig. 11) But Paris beckoned and he began working for a monthly publication called Réalitiés, which was modeled on the American news magazine, Fortune. In 1956, Réalitiés commissioned Horvat to do a photographic story on pimps. Like a detective or private eye, in a film noir or policier, he would sit in his car, watching what went on around him - in the cafés of Pigalle, on the rue Saint-Denis, along the pathways of the Bois de Boulogne. (Figs. 12, 13) For Réalitiés, he also traveled to Algiers, Berlin, back to England, then on to the mines of Belgium (Fig. 14).

Figure 11. Chelsea Flower Show, London, Frank Horvat, 1954

Figure 12. Prostitutes, rue Saint-Denis, Paris, 1956, Frank Horvat

Figure 12a. Prostitutes in a police car, Paris, Frank Horvat, 1956

Figure 13. Prostitutes, Bois de Boulogne, Paris, Frank Horvat, 1956

Figure 14. Miners in Belgium, Frank Horvat, 1959

In 1956, Horvat was commissioned by an American magazine to take photos of ‘Paris by night.’ He went to Le Sphinx cabaret where, with the cooperation of the strippers, he reversed the traditional roles of viewer and viewed. “(H)e portrayed the young women as the masters of the show and presented the voyeuristic spectators as unknowing captives of the stage.” (Figs. 15, 16)

Figure 15. ‘Self-portrait’ with dancer, Le Sphinx, Paris, Frank Horvat, 1956

Figure 16. Le Sphinx, (viewers on view) Pigalle, Paris, Frank Horvat, 1956

In 1957, Horvat met Jacques Moulin, artistic director of Jardin des Modes who suggested that Horvat transfer his stye of urban Parisian scenes to fashion photography. He said okay, as long as he could work with a small format camera, with natural light and settings. Moulin’s timing was perfect. Fashion was relaxing, thanks to Dior. And ready-to-wear made its debut.

According to one critic, Horvat always acknowledged that American and English photographers had already taken models out of the studio and onto the streets. But when he did those things in the late 1950s, in Paris, he created his own style.

One Horvat photo shows a model in a wedding dress on the back of a bus (Fig. 17). Another depicts a model emerging from a metro wearing a cocktail dress, an impatient crowd behind her. (Fig. 18) Other models drank with locals at a bar, (Fig 19) ate with diners in a neighborhood bistro (Fig 20). Models posed with each other (Fig. 21) and with groups of children. (Fig. 22) Recalling the complicity of the strippers whose photographs he took, Horvat chose models who could be in on the joke, not the object of it. “Horvat explored fashion as close-up still life and fantasy narrative," with independent women, striking their own poses, telling their own stories. (Figs. 23, 24)

Figure 17. Wedding gown on bus, Paris, Frank Horvat, 1961, for British Vogue

Figure 18. Monique Dutto leaving the metro, Paris, for Jours de France, Frank Horvat, 1959

Figure 19. Tan Arnold at the Chien qui fume, Paris, for Jardin des Modes, Frank Horvat 1957.

Figure 20. Model with Spaghetti, Rome, for Harper’s Bazaar, Frank Horvat, 1962

Figure 21. Models at Place de la Concorde, Paris, for Jardin des Modes, Frank Horvat, 1958

Figure 22. Model in bride’s dress with children, Paris, for British Vogue, Frank Horvat, 1961

Figure 22. Givenchy hat, Paris, Jardin des Modes, Frank Horvat, 1958, see above Fig. 7

Figure 23. Judy Dent & Maggi Eckardt, London, for British Vogue, Frank Horvat. 1959-60

Figure 24. Deborah Dixon with Marcello Mastroianni, Frank Horvat, 1962

Here’s how Horvat remembered it, “What above all made certain moments seem "decisive" to me was that to transform the "model" into a "real woman", it was not enough to strip her of her layers of artifice: we still needed the little miracle of a gesture, a lock of hair, an angle of view, a ray of light, which suddenly made it credible, and therefore seductive. Some of my sponsors encouraged me, like Hélène Lazareff, founder and director of Elle, when she sent me to photograph fashion in a village in Auvergne – a first comparable, in the microcosm of the women's press, to the first steps of the man on the moon. (Figs. 25, 26)

Figure 25 Models in Auvergne, France, for Elle, Frank Horvat, 1960

Figure 26. Models on the métro, Paris, for Jardin des Modes, Frank Horvat, 1958

Horvat didn’t wait for the ‘Decisive Moment’ he created it. Among his set ups were, according to Horvat, “.. a parody of the adventures of Arsène Lupin, (a) studio reconstruction of a watchmaking boutique, a circus lion that we had delivered to Cartier, Place Vendôme. …”

Horvat wasn’t interested in the dresses the models wore. And he didn’t want his models wearing heavy make up or striking exaggerated poses. He was a story teller so he created anecdotes, which had nothing to do with clothes. Again, Horvat, “I found … ways by which my photos could acquire this character of decisive moments, which continued to seem essential to me…” Once again, Horvat refers to Cartier-Bresson’s phrase that became his mantra as well as that of so many photographers.

“During my first series for British Vogue, I was made to understand that the vagaries of British weather made outdoor shots too unpredictable. I resigned myself to photographing in the studio, but I asked for extras and props, hoping that they would produce unexpected interactions, much in the same way as the events in the street. Vogue did not lack resources, but its studios had never hosted such an assemblage of flea market objects, musical instruments, infants, white Percherons (French breed of horses) and fake retired colonels. I justified these costs by arguing that days lost due to rain would have cost even more.” ‘

Horvat took a break from fashion photography in 1962. For eight months, he traveled from Cairo to Tel Aviv; Calcutta to Sydney; Bangkok to Hong Kong. He stopped in Tokyo (Fig. 27) and Los Angeles and New York; Caracas and Rio de Janeiro and Dakar. He was on assignment for the German magazine Revue. He was prolific but the timing was off. Revue was only able to publish a few of his photos. Most of them remained in the artist’s own archive until now, with this exhibition. (Fig 28)

Figure 27. Plastic Surgery, Tokyo, Japan, Frank Horvat, 1963

Figure 28. Marine Bar, Calcutta, India, Frank Horvat, 1962

Model with a Shadow, New York, Frank Horvat, 1961

Walnut Tree with a shadow, Dordogne, Frank Horvat, 1976

This is surely not the last of the Horvat exhibitions. He kept working and kept innovating until his death at age 92 in 2020. Among his most recent adventures, a compact digital camera that he bought in 2006. About it he wrote, “I once used to say – partly as a joke, partly because it was really one of my daydreams – that I would happily have one of my eyes taken out and replaced by a tiny camera, which would be similar to an eye and allow me – with a blink, for example – to take furtive photos of what I see with the other…”. Horvat was the first photographer to create his own IPad application, called “Horvatland” it comprises over 2000 photographs representing more than 65 years of photography. The retrospectives are just beginning!

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.