Measure of Man, Critical Mass II

Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin (Oct 23 - Mar 24)

Antony Gormley’s exhibition at the Musée Rodin is glorious. If you do nothing more than wander in the garden, you will get your art’s worth, to say nothing of your money’s worth. You sense that something really special, something really different is going on here as you begin to notice statues on the grass, on the paths, on the steps. Which reveal themselves as you walk. These statues - some kneeling, some crawling, some squatting, some sitting, some standing (Figs 1,2) - all face in the same direction, toward the same destination. Like lemmings, automatons, beings without volition, they are on a journey whose end is in sight and is inescapable. They are all headed for Auguste Rodin’s Gates of Hell ‘embellished’ with scenes from the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy, (Fig 3) The Inferno.’ Rodin’s Gates, like Dante’s own, bear the inscription, “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’entrate,” (“Abandon all hope, those who enter.”). “On the wall behind the writhing characters in Rodin’s “Gates”, Gormley perches “Domain Field”, (Fig 4) a fragile silhouette of a figure made of stainless steel bars - the human form in essence, a relic, sometimes glimmering in the sun, then fading as the weather grows overcast. (Jackie Wullschläger Financial Times, Oct. 2023)

Figure 1. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin (from kneeling to standing)

Figure 2. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin (standing)

Figure 3. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley with Gates of Hell, Rodin in the distance, Musée Rodin

Figure 4. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Domain Field above Gates of Hell, Musée Rodin

Wullschläger describes the statues as “(s)naking past topiary and late blooming roses, with the neoclassical Hôtel Biron, paragon of Enlightenment architecture, as backcloth.” (Fig 5) As this critic and others have noted, Gormley’s exhibition opened as news was arriving about the Hamas attacks on Israel, as the unrelenting news about Ukraine kept getting worse, as museums and other public buildings in Paris were forced to evacuate, after telephone calls warning of bombs were received. The Musée Rodin may have been a respite from that for us, but not for those figures inexorably making their way to The Gates of Hell. Context is compelling.

Figure 5. Musée Rodin (Hôtel Biron) Paris

Gormley has exhibited this group of statues that he calls Critical Mass II at other venues. Among them, the Forte Di Belvedere, high above the city of Florence. (Fig 6) Ginevra and I hiked up there one day last May. (Fig 7) To experience the gorgeous panoramic view of the birthplace of the Renaissance. Located on the highest hill of the Boboli Gardens, it’s often referred to as “the most beautiful terrace in Florence.” It was built between 1590-1595 with a dual purpose: to protect the city against invading armies and to protect the Medici family against internal rebellion (there is direct access from the Pitti Palace via the Boboli Gardens). Three hundred and fifty years after it was built, the Italian Army gave the Fort to the City of Florence. Like swords into plowshares, it is now used for art exhibitions and cultural events.

Figure 6. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, Italy

Figure 7. Ginevra & me on Forte Di Belvedere, Florence, Italy

To Gormley, the Fort is “an extraordinary example of a natural hill transformed into an artifact.” Gormley decided not to exhibit sculptures that matched the scale of the site, but to exhibit human size sculptures to contrast with the “mighty mass and form of the Fort” itself.

Also at the Forte, Gormley wanted to create “a dialogue between anatomy and architecture.” For example, he placed a single figure “against the wall in an entrance tunnel” to underline “the contrast between the idealism of a Renaissance city and…(a) homeless person sheltering in a city doorway.”(Fig 8) And in the old gunpowder store, he placed a single sculpture constructed from pure cubes, (Fig 9) to replace “the idealization of the statue placed on a plinth (with) the pathos of the exposed prisoner on a box.”

Figure 8. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, Italy

Figure 9. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, Italy

The thesis is antithesis with Gormley, the glorious with the inglorious, the focus of everything, even statues composed of cubes and cylinders, on the human form, with all its frailties and foibles.

The Musée Rodin is, of course, another venue, with its own scenic and psychic demands. After we’ve discovered and pondered the significance of the “twelve body forms (in the garden that) “installed in a linear progression, from fetal to star-gazing, recall the ‘ascent of man’ (according to Gormley)” we move on to the Marble Galerie. A space that is never open, it is always visually accessible through six huge windows. This exhibition is no exception. Except that in addition to glimpses of Rodin’s often voluptuous, marble statues, now, pressed to the front of each window is an iron figure, strung out, Giacometti like, penis erect, at attention. (Fig 10) “They are stick-thin … skeletal frames “between being and nothingness”, according to Gormley.

Figure 10. Figures, side view, Antony Gormley, Marble Galerie, Musée Rodin, Paris

We make our way next into the former chapel that is now the museum’s temporary exhibition space. Here we are confronted with sixty statues (well, 60 minus the 12 statues in the garden) made from twelve body forms, each cast five times. There are intentional imperfections, you can see how the statues were cast, there are buttons and drips of poured metal that haven’t been polished smooth. (Figs 11, 12) The postures and presentation of the different statues run the gamut from contemplative to completely absurd. Some figures press their heads against walls, others are suspended, hanging from the ceiling. (Fig 13) ‘The work references the materiality of sculpture and our dependency on the materiality of the body, both being subject to position, context, and jeopardy’ (Gormley). In the center of the space is a pile up, a crash of many of bodies, (Fig 15) which, according to the artist, “reflect the shadow side of any idea of human progress…” They are intended to be “stumbling blocks that stop the viewer in their tracks. I want to encourage the viewer to think again about who they are and how they negotiate the spaces around them.”

Figure 11. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 12. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 13. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 14. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 15. Critical Mass II, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Finally we enter the Hotel Biron, the Rodin museum itself. Gormley has come as a guest. An important guest, like a Duke or Duchess at one of the interminable dinner parties that Proust never stops describing. Gormley is the sort of guest anyone would welcome to their dinner party. A guest who is polite, who engages thoughtfully with his host and the other guests.

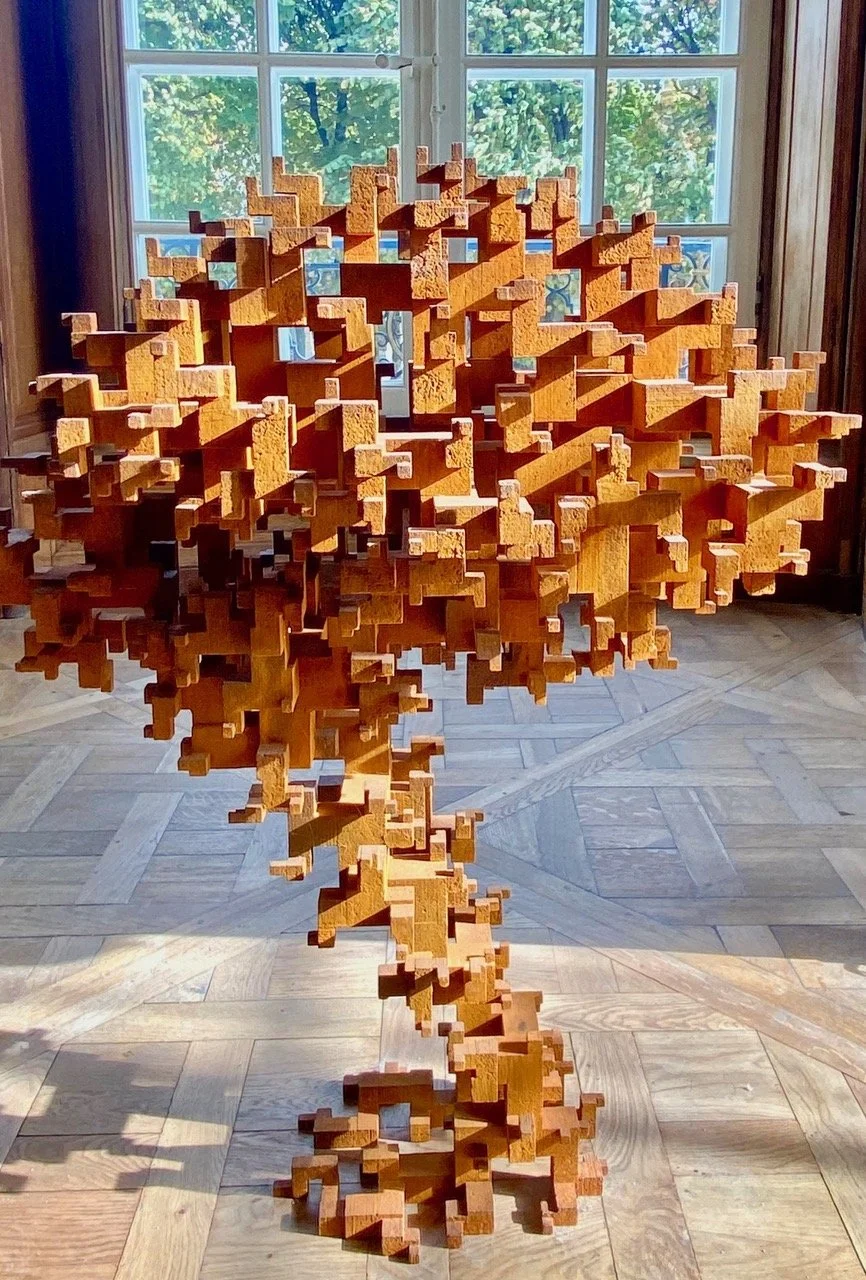

Since this is a conversation and not a competition and since Rodin is the master of the human form in marble, Gormley has brought wood and metal, mostly cubic, sculptures with him. They all refer in some way to the human body - either its interiority or its composition but not in a Rodin way, not in a sensual way. (Figs 16, 17)

Figure 16. Crouching figure, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 17. Crouching Figure, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

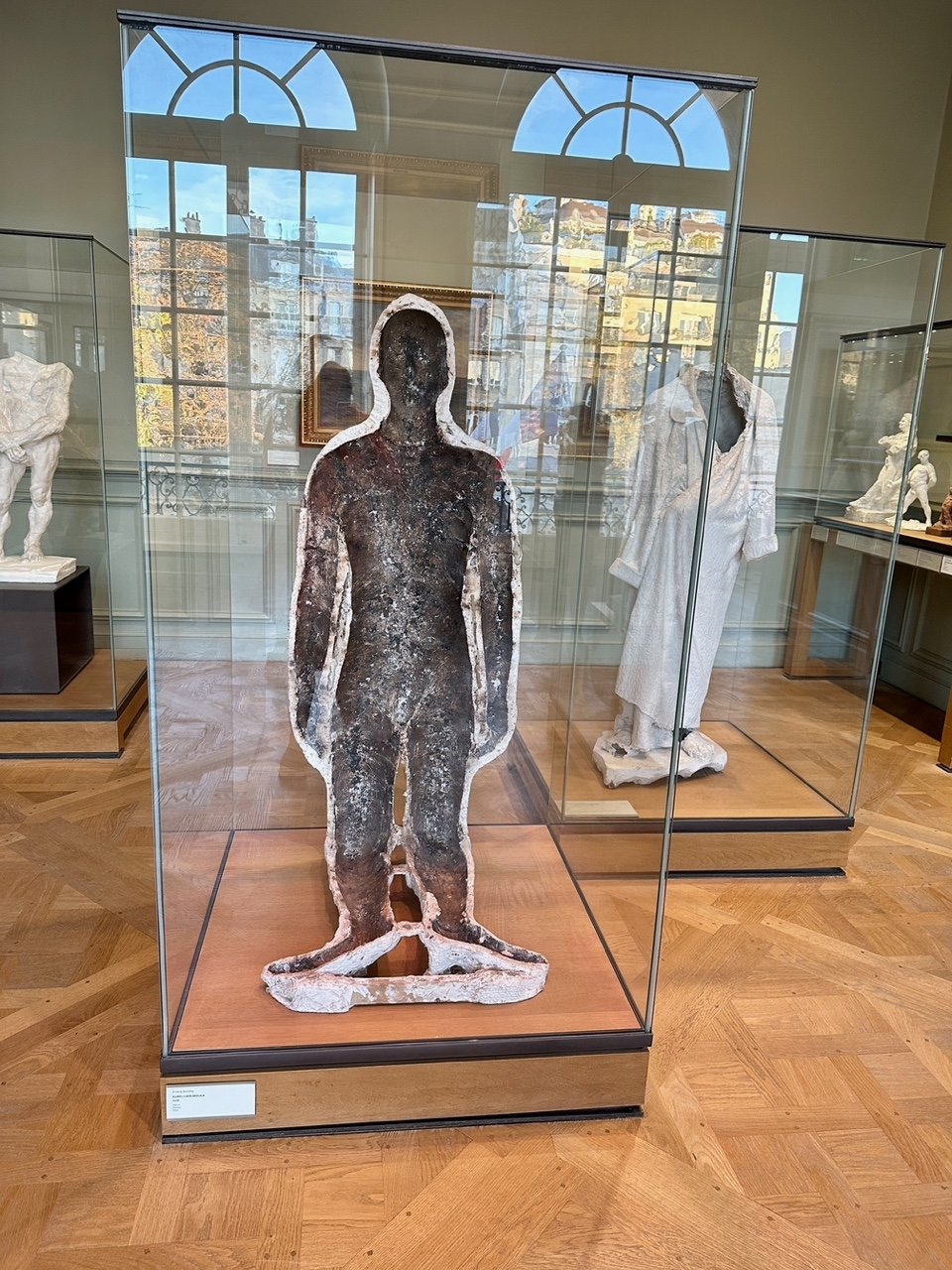

Gormley has also brought working models which he displays alongside Rodin’s maquettes. Since both artists use molds and plaster, one of Gormley’s life-size plaster molds is right at home next to Rodin’s Study for Balzac’s Dressing Gown. (Figs 18, 19) Gormley uses different materials that his host, his older colleague, but the juxtaposition of the two artists’ work establishes connections and conjunctions.

Figure 18. Gormley life size plaster mold & Rodin Study for Balzac’s Dressing Gown, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 19. Rodin, Balzac bust, Gormley piece, Musée Rodin, Paris

There are smaller works here, too - some are fragments, some are models (Figs 20, 21) These are in glass cases, sometimes alone, sometimes integrated with works by Rodin and other sculptors exhibited here permanently.

Figure 20. Display Case, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 21. Display Case, Antony Gormley, Musée Rodin, Paris

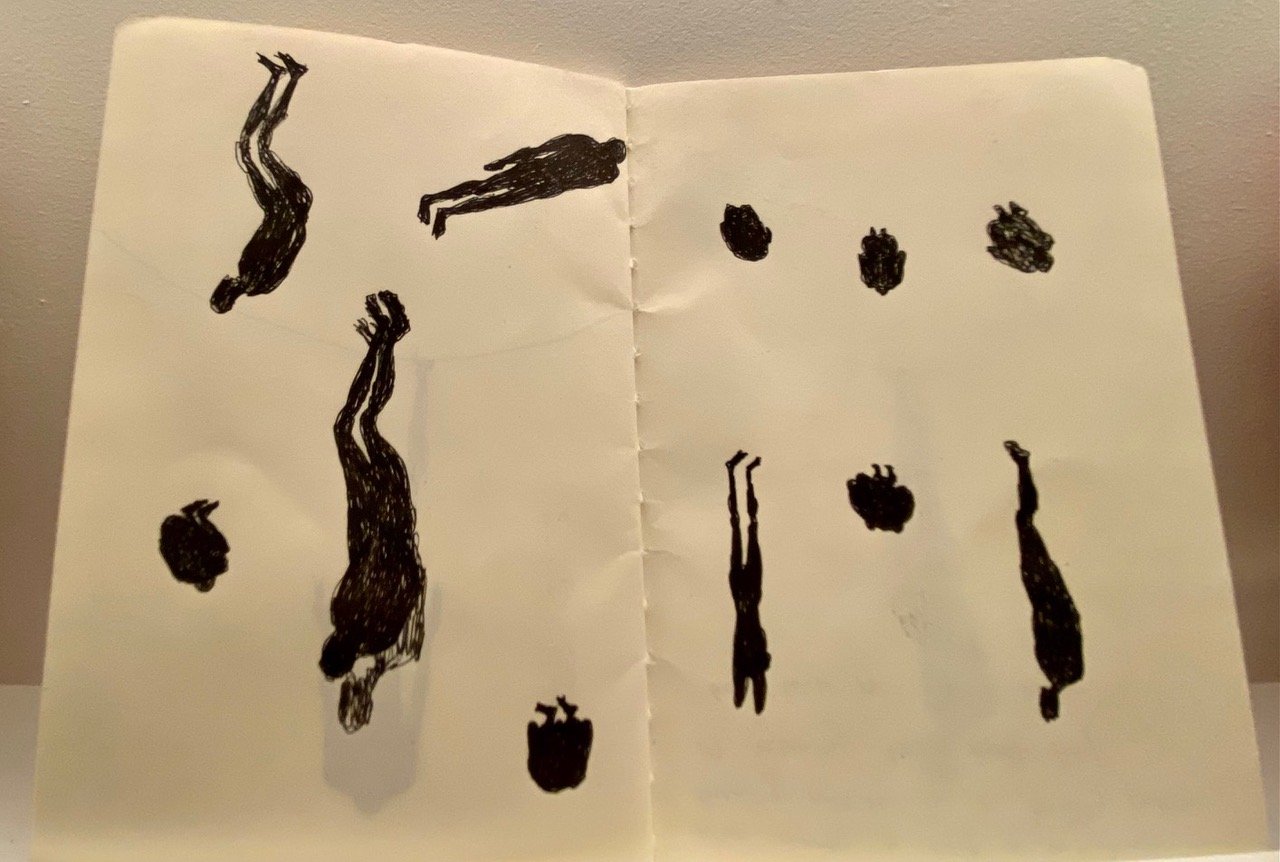

In other glass cases, these along a corridor at the end of the exhibition, Gormley has brought with him more than 200 sketchbooks spanning 40 years of his career. They establish the genesis and the progression of his ideas and his projects. A number of which we have just seen in the garden and in the exhibition space. (Figs 22, 23)

Figure 22. Gormley sketchbook, Musée Rodin, Paris

Figure 23. Gormley sketchbook, Musée Rodin, Paris

In an interview with Lisa Barnard, (Oct 2023), Gormley admitted that as a young artist, he revolted against Rodin’s “oily sexuality,” and “looked at the work of American minimalism, (like) … Donald Judd and Bruce Nauman …who liberated sculpture into a more honest relation with the way that we relate to materials.”

As he matured as an artist, Gormley realized that “(a)t some point I would have to come back to an artist whom I had rejected as being irrelevant…”

This exhibition was that occasion. For Gormley, “doing this show has been an amazing learning experience … because in a sense it is (Rodin’s) plasters… that tell us most about him and his working method. … I learned a lot…” Indeed, Gormley learned that Rodin’s creative process was collaborative, like his own.

According to Gormley “(t)he reason that Rodin remains a key source of inspiration and renewal for sculpture is the way that he liberated it by combining ancient and modern methods and materials …” Rodin was “the originator of modern sculpture (who) took full advantage of the freedom to experiment, armed with all the means of an emergent industrial age and its ability to mechanically produce in profusion.” (Fig 24)

Figure 24. The Thinker, Legion of Honor, San Francisco & Robin Williams (other Thinkers are at Stanford, Philadelphia, Paris…)

Gormley explained that when he accepted the invitation to exhibit his work in the “shrine to one of the key players in the evolution of European sculpture…I didn’t want to take over the place. It was the opportunity for making a conversation through the silent, still language (of sculpture). The foundation of the whole show was, can we just take a few words (works), one of Rodin’s and one of mine, and allow them to share the same space and talk to each other about their different attitudes to the body.”

For Gormley, the figures he exhibited at the Belvedere in Florence in 2015 and which are currently on exhibition in the garden and the temporary exhibition space at the Musée Rodin (Critical Mass II ) are “the most concentrated example of my attempt to reanimate and re-purpose the power of the body in the art of sculpture.”

You will be as pleased as I was to know that at this dinner party, this exhibition, the guest of honor (Gormley) cares about us (the visitor). Because without us, there is no party. Without us, who knows if the tree falling in the woods makes a sound. Because “(w)ithout being seen or physically experienced, the work has no value, no function. Once it is in relation to the movement of people it has a kind of transferred energy.” So now you really must see this exhibition, they are saving a seat for you. (Fig 25)

Figure 25. I’m not exactly sure what he was asking me to do !!!!!

Copyright © 2024 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you!