Musées Galore sur la Côte d’Azur

A week on the Côte d’Azur, courtesy of HomeExchange.

It was my first HomeExchange experience. You know the online platform for home owners who like to travel but don’t want to stay at hotels or Airbnbs. You describe your home and location in words and photos. Then you browse through the site, shopping for places you want to stay. Better than renting because everyone is on their best behavior. They treat your property the way they want you to treat theirs.

I had been meaning to join for years. And as soon as I did, I began receiving emails from fellow HomeExchange members, interested in staying in my pigeonnier

in the Dordogne. And that is how I found myself in the Cote d’Azur in September.

Before last September, I had never stayed in this part of France. I had driven through it but never to it. It was time for a new experience.

We flew to Nice, picked up our rental car and headed into the arrière pays, to St. Jeannet, (Figure 1) home for the week. I had never heard of St. Jeannet but almost everyone I asked here in Paris, had. So, I was ready.

Figure 1. The prickly cactus I walked by at least twice every day, same cat every day too

Traveling with kids for so many years taught me an important lesson as I planned - don’t save the best for last. Because well, because you just never know.

So, the first day on the Côte d’Azur we drove to St. Paul de Vence for the only ‘must see’ on my list. Le Fondation Maeght. (Figure 2) A place I have known about it ever since I began studying art history in college. The drive from St. Jeannet was one hair pin turn after another. A short distance that took forever on the kind of roads I always avoid. Our destination was worth the drive so I tried to forget that our return would be the same. As every trip proved to be, short distances, long drives, hairpin turns.

Figure 2. Fondation Maeght

The Fondation is a modernist building set into a landscape brimming with playful sculptures created by the artists who had become Aimé and Marguerite Maeght’s friends over the years. (Figure 3) The building was designed by the Catalan architect Josep Lluís Sert who was by then the Dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (architecture school). Using local stone and brick, as well as some poured concrete, (Figure 4) Sert ‘reinterpreted the codes of a Mediterranean village – the whiteness, the earth, the patios.’ He created a building that is integrated into its site and doesn’t dominate it.

Figure 3. Fondation Maeght, exterior

Figure 4. Fondation Maeght designed by Josep Louis Sert

Ceramic figures by Joan Miró (Figure 5) and a monumental stabile by Calder (Figure 6) greet you as you enter the Fondation grounds. As you wander further, you come upon the Giacometti Courtyard populated by iconic sculptures by Alberto Giacometti (Figures 7, 8).

Figure 5. Fondation Maeght, sculpture by Joan Miro

Figure 6. Fondation Maeght, Stabile by Alexander Calder

Figure 7. Fondation Maeght. Sculptures by Alberto Giacometti from above

Figure 8. Archival photo, Alberto Giacometti at Fondation Maeght, 1964

The Miró Labyrinth was made specifically for this site - of ceramics, marble, iron, bronze and concrete. (Figure 9) To explore the Labyrinth you follow a white line painted on the walls, a reference to Ariadne’s thread that Theseus used to escape the labyrinth. At the end of this labyrinth, the fantastical beasts of Miró’s personal bestiary await. (Figures 10 & 11)

Figure 9. Fondation Maeght, Miro Labyrinth

Figure 10. Fondation Maeght, Labyrinth of Miró, beasts

Figure 11. Fondation Maeght, Labyrinth of Miró, fountain beasts

There is also a chapel, dedicated to St Bernard, a memorial to the Maeght’s son Bernard who died of leukemia in 1953 at age 12. A carved 12th century Spanish crucifix, a modern slate relief Stations of the Cross and a stained-glass window by Georges Braque, make this a beautiful and simple place of remembrance.

It was Bernard’s death that gave life to the La Fondation. It became a way for heartbroken parents to memorialize their son and deal with their grief. There were no private art collections in France at the time but they had visited private collections in the U.S., the Barnes in Philadelphia, the Guggenheim in New York and the Philips Collection in Washington, D.C. This last of which was created by the museum’s founder, Duncan Phillips, following the deaths of his father in 1917 and his brother, a year later, of the flu epidemic. Phillips wrote that, “(s)orrow all but overwhelmed me, then I turned to my love of painting for the will to live.” He and his mother founded the museum in late 1918 and opened it to the public in 1921. There are other examples of grief leading to altruism. Stanford University, for example, was founded by Leland Stanford following the death of his only child of typhoid fever at the age of 15.

Last summer, the temporary exhibition at the Fondation was on the Giacometti brothers, father and cousin. It was a surprisingly interesting exhibition. I say surprisingly because for the past few years we have been inundated by exhibitions of Alberto’s strung out sculptures and Diego’s furniture and fixtures. But this exhibition explored the family’s work in painting and architecture as well as sculpture and decorative arts. (Figures 12, 13)

Figure 12. Fondation Maeght, Diego Giacometti ‘Chat Maître d’Hôtel’, circa 1965

Figure 13. Fondation Maeght, Alberto Giacometti light fixture and furniture

How was it, beyond the death of their beloved son, that the Maights were in a position to establish “the first private foundation dedicated to the visual arts in Europe” at St. Paul de Vence. This is what I learned, Aimé Maeght studied lithography at school in Nîmes. In 1926 at the age of 20, Maeght got his first job with a printer in Cannes, specializing in advertising. A decade later, and only by chance, Pierre Bonnard asked him to design a lithograph. That chance encounter set the course of his life in motion.

His life was shaped by external events as well, of course. When the Nazis occupied Paris, the Côte d'Azur was under Italian protection. Artists fled south and settled in Nice and Cannes. So did collectors. Parisian art dealers established themselves there, too.

And in 1941, on the advice of Pierre Bonnard, Maeght decided to become an art dealer. One gallerist friend of his used his gallery to hide his real activities. Jean Moulin, the hero of the French Resistance. When Moulin was arrested by the Nazis, Maeght knew it was time for him to move on, which he did, to nearby Vence. His politics were well enough known that when he opened a gallery in Paris after the war, it was the artists of the resistance who joined him. Artists who had made lives for themselves in the Midi during the war. The first artist Maeght exhibited in Paris was Matisse. Soon Bonnard, Braque, Léger, and Picasso had their work exhibited at Maeght’s gallery. Soon, he began exhibiting Miro, Calder and Giacometti.

Through the 1950s, the gallery stayed on the cutting edge of the art world. But then as one reviewer put it, Maight moved ‘from the age of adventures to that of consecration’. And his artist friends were eager to help him realize his dream of a Fondation and set about creating site specific works of art for it. The permanent collection may reflect the heyday of the Maeght’s Paris gallery on rue de Téhéran (which was purchased by one of Maeght's employees), Daniel LeLong. But the Fondation stays relevant through its temporary exhibitions and the events it sponsors.

After a little retail therapy in the wonderful book store, we drove over to the tiny Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence designed by Henri Matisse. (Figures 14, 15, 16) Filled with thoughts of art, I almost didn’t notice the ride back to St. Jeannet or the uphill hike from the parking lot outside town to the apartment on the tiny pedestrian street where we were staying. (Figures 17, 18). An everyday occurrence, alas.

Figure 14. Chapelle du Rosaire, Vence, photo of Henri Matisse who designed it

Figure 15. Chapelle du Rosaire, Vence, interior, designed by Henri Matisse

Figure 16. Chapelle du Rosaire, vestments designed by Henri Matisse

Figure 17. One of the pedestrian streets from parking lot to apartment, St. Jeannet

Figure 18. View from my balcony one morning in St. Jeannet

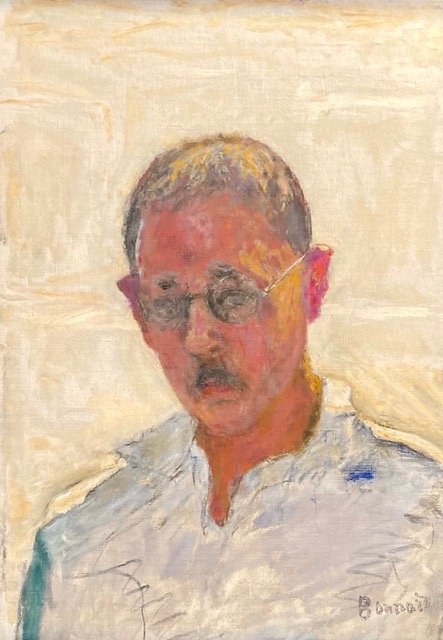

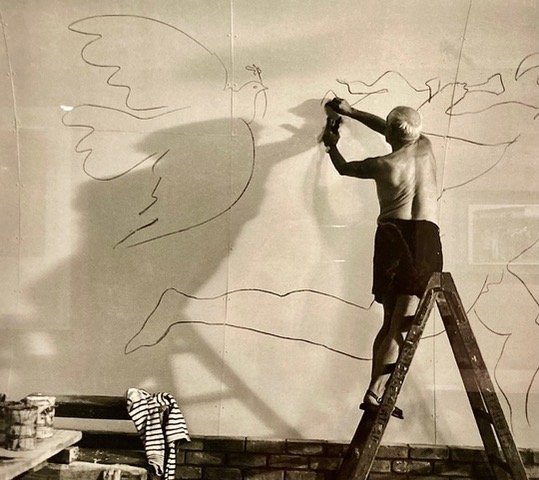

Another day, we drove to the Ferdnand Léger Museum, (Figures 19) which had an exhibition highlighting Leger’s socialist and humanist works with a section devoted to a panel he created with Charlotte Perriand for the Universal Exposition of 1937. (Figures 20, 21) The Pierre Bonnard Museum was close by and after a harrowing trip along some of the narrowest roads we had yet encountered, we arrived. To enjoy the building, a first rate video of Bonnard’s life and a temporary exhibition of artists’ self portraits. (Figures 22, 23) The Picasso Museum in nearby Vallauris focused on the master mastering a new skill, ceramics. Picasso decorated the nearby Romanesque chapel with panels depicting the horrors of war and the rewards of peace. (Figs 24, 25)

Figure 19. Exterior view of Ferdnand Léger Museum in Biot

Figure 20. Panel by Fernand Léger and Charlotte Perriand for Universal Exposition, 1937

Figure 21. Explication of Léger / Perriand panel, 1937

Figure 22. Bonnard Museum exterior. Cannet

Figure 23. Self portrait, Emile Bonnard

Figure 24. La Guerre et la Paix panels, Picasso, 1952, Romanesque Chapel, Vallauris

Figure 25. Picasso working on his Chapel of War & Peace Panels, 1951, Vallauris

When I visited these museums in September, I didn’t understand why so many artists had chosen to build their museums in the Midi rather than in Paris. Then I saw the exhibition ‘Picasso the Foreigner’ at the Musée de l’immigration. As the curator of that exhibition noted, when Picasso left Paris definitively for the Midi in 1955, he chose to associate with artisans rather than academic artists; chose the countryside over the city and chose the south over the north. Now I am wondering why Giacometti’s widow decided to create a museum for her husband in Paris rather than the Midi.

Another day, another couple of museums, except not. We didn’t make it either to the Matisse or Chagall Museums in Nice. Long story, never mind, I’ll get there another time. I did get to Nice one day and visited a museum I didn’t have on my list. But we parked as close as we could to the simple restaurant said to have the best socca (chick pea pancake) in the city. (Figure 26) The parking garage was underneath MAMAC, Musée d’art Moderne et d’art Contemporain. The entrance was presided over by a Niki de Saint Phalle dragon and a Calder stabile. (Figure 27). The temporary exhibitions and permanent collection are so intelligently displayed that it was a joy to explore this wonderful museum. I fell in love with Niki de Saint Phalle (Figure 28). And was happy to see Yves Klein (Figure 29) and an early Christo (Figure 30). And we did walk around the Old City of Nice (Figure 31) and unexpectedly bumped into a statue of Michelangelo’s David.(Figure 32)

Figure 26. My first plate of socca. Tasted great. Can’t remember where, Nice

Figure 27. Entrance to MAMAC presided over by Niki de Saint Phalle Dragon & Calder Stabile

Figure 28. Nana noire upside down, Niki de Saint Phalle, 1965-1966, MAMAC

Figure 29. Yves Klein Room, his famous, IKB » (International Klein Blue), 1960. MAMAC

Figure 30. Store Front, Christo, 1962. MAMAC

Figure 31. Wandering around Old Nice

Figure 32. Bronze Replica of Michelangelo’s Statue of David, Nice, installed 2015

One day, we met up with some people we know in Antibes who knew of a great coastal walk along the Mediterranean. Which was fabulous but which, quite honestly, was exactly like the coastal walk I take at Land’s End in San Francisco, minus views of the Golden Gate Bridge, naturally. (Figures 33, 34) I was very proud of myself for not mentioning the Picasso museum in Antibes that I would have loved to have visited.

Figure 33. Antibes Coastal Walk

Figure 34. Land’s End Coastal Walk, San Francisco

Although at first I only had one ‘must see’. Research proved otherwise. Day 2 was the Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild in St. Jean-Cap Ferrat. (Figure 35) It is run by Culturespace, the folks who bring you the temporary exhibitions at the Musée Jacquemart-André and the sound and light shows at the Ateliers des Lumières. So I was pretty sure that it was going to be well done. And of course with the current exhibition at the Musée Nissim Camondo by Edmund de Waal, a descendant of the Ephrussi family, of course I wanted to learn about the villa.

Figure 35. Villa & Gardens Ephrussi de Rothschild, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, 1912

The marriage between 19 year old Béatrice de Rothschild and Maurice Ephrussi was a dynastic one which turned out to be a disastrous one for young Béatrice. (Figure 36) First of all, her husband, 15 years her senior gave her syphilis and she became sterile, and I don’t know what else (but I’m sure it must have been something else, after having seen that film with Meryl Streep about Florence Foster Jenkins who thought she could sing but couldn’t and was suffering from late stage syphilis). Secondly, Maurice gambled … a lot and badly. When his debts reached the equivalent of 30 million or so euros, the Rothschild family, fearing he would use all of Béatrice’s money, forced a divorce. This was in 1904, after 21 years of marriage.

Figure 36. Charlotte Béatrice de Rothschild (1864 - 1934)

So, this villa is not a love story. More of I can have whatever I want, story. In 1902, Béatrice’s husband's cousin, Théodore Reinach (who was the father of Leon Reinach, who was the husband of Béatrice de Camondo whose home is now the Musée Nissim de Camondo ) built a villa on Beaulieu sur Mer . Béatrice visited it, fell in love with the area (who wouldn’t) and did what only very rich people can do. She bought some land and built her own villa. An Italian villa, specifically a Venetian Renaissance villa which she filled with some of the art she had been collecting. The villa is pink because that was Beatrice’s favorite color.

The villa is as light and airy as a place can be, with windows and balconies offering breathtaking views of the Mediterranean. (Figures 37, 38) It is tastefully decorated with antique furniture and porcelain, sculptures and objets d’art, and the occasional oil painting, all set in rooms whose wall and floor coverings are delightfully light. (Figures 39, 40).

Figure 37. Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild

Figure 39. Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild, interior court

Figure 38. Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Figure 40. Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild, interior

The highlight of the villa is the gardens, which I wanted to enjoy leisurely. So, rather than having lunch in the elegant restaurant, we ordered a picnic. And then, with picnic basket and blanket in hand, we wandered around the gardens, all 9 of them, until we found the perfect spot. As the villa’s website explains, the garden was conceived in the form of a ship, to be viewed from the loggia of the house, with the sea visible on all sides. (Figure 40a) It was inspired by a voyage Beatrice had made on the liner Île France. Which was what she named the villa. When Madame was in residence, the 30 gardeners who tended the garden, all dressed as sailors. They must have loved that.

Figure 40a. Exterior from Villa, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

The gardens include the formal French garden with fountains, statues, and basins filled with water lilies. On one end of the park is a replica of the Temple of Love from the Petit Trianon Palace at Versailles. (Figure 41)

Figure 41. French Garden, Temple of Love, after Petit Trianon, Versailles, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

The Spanish garden has a shaded courtyard, aromatic plants and a Gallo-Roman bench. The Florentine garden has a grand stairway and an artificial grotto. (Figure 42) The stone garden has an assortment of gargoyles, columns and other architectural elements from ancient and medieval buildings. (Figure 43) The Japanese garden has a wooden pavilion, a bridge and lanterns. (Figure 44) The exotic garden features giant cactus and other rare plants. (Figure 45) A rose garden is filled with roses, mostly pink. (Figure 46)

Figure 42. Italian Garden Grotto, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Figure 43. Stone Garden, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Figure 44. Japanese Garden, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Figure 45. Exotic Garden, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Figure 46. Rose Garden, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

To eat what turned out to be a surprisingly good lunch, (Figure 47) we chose the garden in front of the villa so we could watch an army of florists prepare for an event, I’m guess a wedding. (Figure 48) Between them and us was a grand basin where water jets spouted in time to the classical music, a water ballet. It doesn’t get any better than that. (Figure 49)

Figure 47. Picnic lunch in garden of Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Figure 48. Wedding Preparations, Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild

Well, those reminiscences have done their job. I’m feeling better and looking forward to my next trip to the Côte d’Azur. I hope you’re inspired to make plans too!

Figure 49. Video of the waterworks at Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.