Simply ’the thing to wear’

Kimono: Musée du Quai Branly

There’s a kimono exhibition at the Musée du Quai Branly. It’s terrific, but I couldn’t understand why it was there. Two other museums in Paris would seem a better fit. The Musée national des arts asiatiques, the Guimet, where I saw a beautiful kimono exhibition a few years ago. (Fig 1) And the Palais Galliera, the Musée de la Mode de Paris, where I have seen many fine exhibitions celebrating fashion and design.

Figure 1. Kimono Au bonheur des dames, Exhibition at Musée Guimet, 2017

Most of the Branly’s permanent collection was acquired through conquest or colonization. Japan was neither colonized nor conquered (well, not until Harry Truman had two atomic bombs dropped on it). Most of the objects in the Musée du Branly’s permanent collection were not created as ‘art’ to be hung on walls or placed on pedestals but to be used during rituals and ceremonies. Kimonos were made to be worn, but we know the historical ones mostly through woodblocks and screens. (Fig.2)

Figure 2. Edo period woodcut with figures wearing kimonos

So, why an exhibition about kimonos at the Musée du Quai Branly.? Turns out, the answer is simple. The Quai Branly had space when the exhibition’s organizers were seeking a venue. And therein lies the sad tale of this marvelous exhibition.

The exhibition was conceived and created by the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Department of Asian Art, specifically by Anna Jackson, the head of the department, whose own research has focused on kimonos. The exhibition ‘Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk’ (do you love alliteration as much as I do?) opened at the V & A in 2020. To great fanfare and rave reviews. Then, just a week later, museum doors were shuttered all over the world. The exhibition became a casualty of Covid.

I reviewed an exhibition about the portrait painter Hyacinthe Rigaud at the Chateau de Versailles. It was sumptuous. It was on view for just a few weeks, Covid again. Nobody died, but lots of people who had put their hearts and souls into researching and writing and designing the exhibition surely mourned its premature and untimely demise. That exhibition had a single venue, it couldn’t be extended, another exhibition was scheduled for the space, borrowed paintings had to be returned.

This kimono exhibition was intended to travel and so it has. After the V & A exhibition was cut short in London, it traveled to Sweden. Bad luck followed as museums closed their doors for a second time. And now the exhibition is here, in Paris, at a museum not especially appropriate, in a space not exactly ideal, but here nonetheless for those of us lucky enough to be here, too.

A few days after the Victoria and Albert Museum was forced to close its doors, Anna Jackson narrated a 5 part (5-6 minutes each) guided tour of the exhibition which is still available and which you should really watch.

I read an interview with the exhibition’s designers. Turns out, it was their first exhibition. Their expertise is store windows for brands like Hermès and Nike. They didn’t know much about kimonos, but they do know a lot about storytelling. And that’s exactly what the job of an exhibition designer is. To present the material and information that the curators and scholars have prepared, in a coherent and compelling way. The head of the design studio, Robert Storey, put it this way, ‘We had to create this narrative to make the exhibit feel discoverable. …. We always think, "how do you create moments of wow?” They apparently found them. (Figs.3, 4, 5)

Figure 3. ‘Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk’, V &. A, London, Robert Storey design

Figure 4. ‘Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk’, V &. A, London, Robert Storey design

Figure 5. ‘Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk’, V &. A, London, Robert Storey design

The exhibition in Paris is simply called, Kimono (although I did seen a non-alliterative subtitle, ‘from Samurai to Pop Culture’ somewhere). It progresses chronologically and thematically through three distinct periods. The first, ‘the kimono in Japan’ during the Edo Period (1603 to 1868). (Fig. 6) The second, “the kimono around the world" from the opening of Japan to the West in the 1850s to the early 20th century. (Fig. 7) The final section,"the transformed kimono,’ focuses on modern and contemporary Japanese and Western designers. (Fig. 8)

Figure 6. Men and women at tea house, Edo period, Woodblock print

Figure 7. Mariano Fortuny, 1920

Figure 8. Alexander McQueen, 2015

The kimono, like so much else in Japan, was imported from China. It arrived in the 7th century, was popular with the wealthy classes in the 12th century and became the principle item of dress for everyone in Japan in the 17th century. What began as an undergarment worn by the Japanese aristocracy was transformed into outerwear worn by the samurai and eventually by people from every strata of Japanese society.

What makes the kimono so special? How it differs from Western clothing is a good way to answer that question. Western clothing accentuates the body of its wearer. Bodices are cut low to amplify the bosom, waists are cinched to make them appear smaller, bustles are attached to make the buttocks look fuller. (Figs. 9, 9a) Men’s clothing too, is tailored to accentuate broad shoulders, slim waists, shapely legs. (Fig. 10)

Figure 9. Kimono vs Western attire

Figure 9a. Ladies in Waiting with Empress Eugenie, Winterhalter, 1855

Figure 10. Louis XIV by Hyacinth Rigaud

The Kimono, which in Japanese means “that which is worn” or more prosaically, the "thing to wear,” is the antithesis of a western garment. For a kimono, the body is irrelevant, the flat surface of the single bolt of cloth from which the kimono is made, is the point. Instead of enhancing or exaggerating the body, the kimono ignores it. It is not tailoring but pattern and fabric and color that define the kimono.

What might seem at first glance to be simple, is anything but. We’re talking about Japan after all. There are rules and regulations. Every aspect of the kimono has been codified and standardized. Each part of the kimono has its own name. Each step for making the kimono has its own rules.

The sleeves of a kimono are so significant that to put on clothes in Japanese is “to pass one’s arms through the sleeves.” There are six different ways to tie an obi, the belt or sash of a kimono, that keeps the kimono closed. Anna Jackson explains in one of her videos, that while luxury kimonos survive, obis do not because after being tied and untied, they wore out and were tossed out. When Japanese kimono makers began making kimonos for the western market in the 19th century, the obi often became an attached sash to make it easier for Western women to tie them.

There is no difference between the form of the male kimono and the form of a female kimono. No difference in form between the kimonos worn by young girls and those worn by married women. Distinctions are made with colors and ornamentations; with the quality of the materials and the decorative patterns. Status and wealth; changing fashion; and ever changing sumptuary laws are all here to be read by those who know the history of kimonos. (Figs. 11, 12) As one scholar notes, the rigidity of Japan’s sumptuary laws can be gauged by the efforts that were made to flaunt them. For example, when the color red was outlawed for outer kimonos, red began showing up on kimono linings and undergarments.

Figure 11. Women shopping and shop assistant (right), Edo period woodblock

Figure 12. Male Kabuki actors, Edo period woodblock, 1854

In her video, Anna Jackson tells us that merchants were considered just a necessary evil in Japan. They profited from the labor of others. So it isn’t surprising that the strictest sumptuary laws take aim at them. Merchants are reminded that “they are to work so as not to inconvenience samurai and farmers.’

Kimonos reached the height of their popularity in Edo, which was both a place, present day Tokyo and a period, 1605 - 1868, when the Tokugawa family, the Tokugawa shogunate, ruled Japan. In Edo, or actually just outside it, in the Yoshiwara, or pleasure (aka red light) district, was where the Kabuki theaters were located and the courtesans and then the geishas, lived. (Fig.13)

Figure 13. Yoshiwara, Edo, Japan

Kabuki originated early in the Edo period as a form of theatre which combined dramatic performances and dance. Originally the actors were women. When women were barred from performing in 1629, they were replaced by men. And like the women before them, men played both male and female parts - just like Shakespeare’s England.

Kabuki performers and courtesans (high end prostitutes) and later, geishas (women skilled in the traditional arts of dance, music, singing and conversation), became fashion icons. Woodblock prints of them, called ukiyo-e, ‘pictures of the floating world,’ were cheaply produced and widely disseminated. They provided information about what these stars were wearing. (see above Figs. 2, 6, 11 -13)

As Jackson notes, when we think of fashion, we think of Europe. But she and her team wanted to show that fashion has flourished in Japan, at least since the 1600s. “Courtesans were early models: woodblocks show them poring over new patterns and fabrics. Prints of them wearing new kimonos (advertised) … both brothels and clothes sellers. The costumes of actors in the kabuki theatre were also studied and copied. The check design of an obi worn by Sanogawa Ichimatsu (Fig. 14) still carries his name.”

Figure 14, Sanogawa Ichimatsu, woodblock, 1751

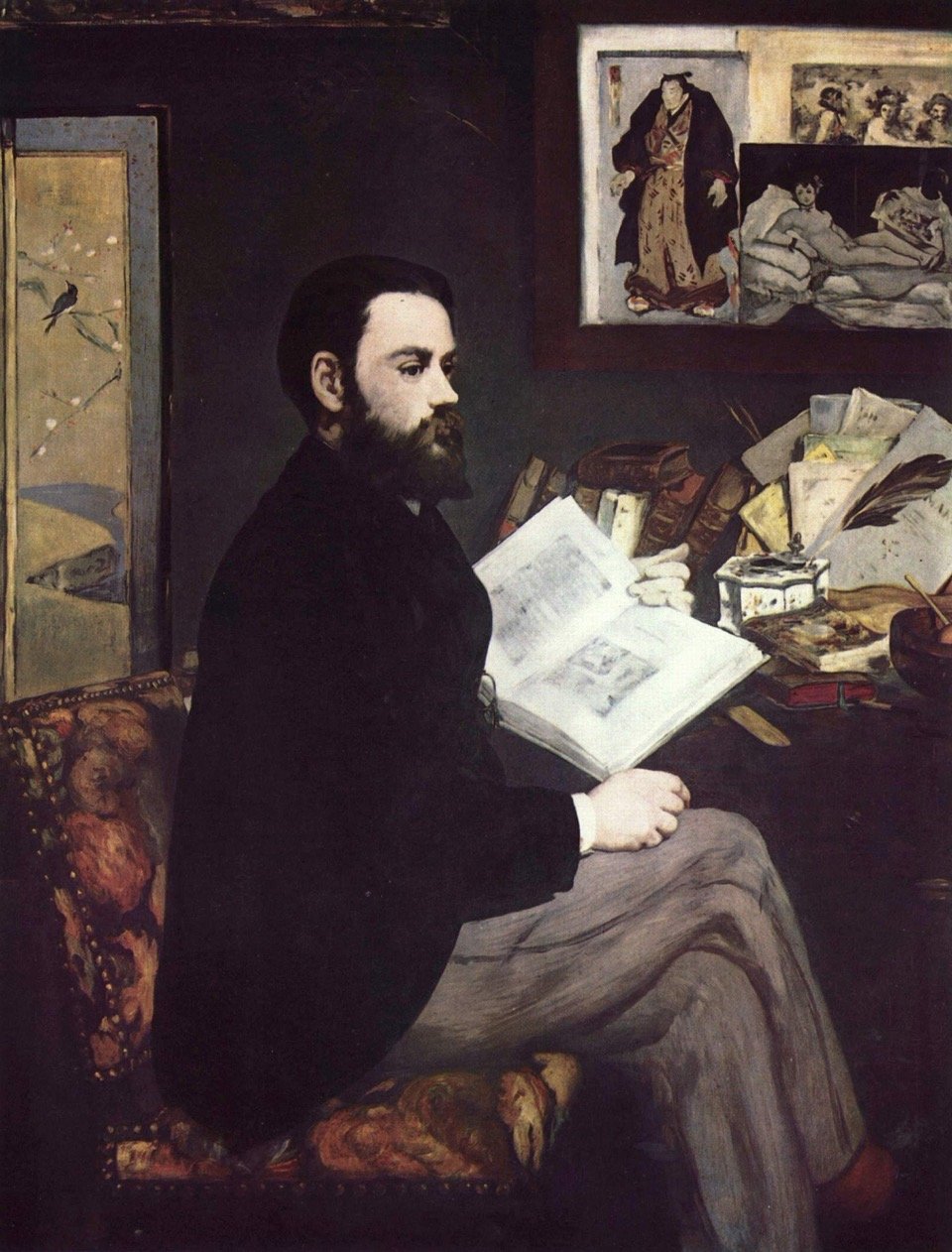

We know how influential Japanese prints were on European artists (Fig.15). Couturiers and the women they dressed just as eagerly embraced the kimono. In canvasses by artists like Gustaf Klimt, Claude Monet and James Tissot, (Figs. 16, 17) we see their sitters posed in kimonos designed by Madeleine Vionnet and Paul Poiret who, in 1906, presented “his first collection to be worn without a corset, based on the loose-fitting kimono.” (Fig. 18)

Figure 15. Zola, Edouard Manet, 1868 (Japanese print on the wall to the right)

Figure 16. A Japanese at her bath, James Tissot

Figure 17. Mme Monet in Japanese Costume, Claude Monet

Figure 18. Opera Coat, Paul Poiret, after 1906

Kimonos provided a much appreciated alternative to restrictive western dress just as women were revolting against the painful, debilitating effects of the corset. Kimonos arrived with a pedigree that permitted their easy assimilation into high fashion. There’s a story that Anna Jackson tells of a woman who designed under the name Lucile (Lady Duff-Gordon) who became famous for what she wore as she fled the sinking Titanic - her squirrel fur coat over her mauve silk kimono.

As Will Heinrich, in his NYT review of last year’s Kimono exhibition at the Met, notes,“the truth is that Japan and the West have been busily emulating and exoticizing each other at least since the 1850s, when Japan opened to the West. Japanese textiles appeared at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle and the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair.”

According to Jackson, the Japanese knew exactly what they were doing when they began to export kimonos in the late 19th century. “Japan has always had agency about how it has exported its dress and how it speaks of its dress in a foreign context.” Japan had no heavy industry to sell, so kimonos and textiles became the obvious export. Using imported Western textile technologies, Japan began mass producing less intricate kimonos for lower prices. New dyes meant bolder colors and Art Nouveau and Art Deco designs introduced entirely new motifs to integrate and explore.

After World War II, most Japanese started wearing Western dress. Kimonos were put away and taken out for special occasions only, like weddings and tea ceremonies. I have told you that Yayoi Kusama brought a box of kimonos (Fig. 19) with her when she moved to New York in the 1950s - to wear when she needed attention, to sell when she needed money.

Figure 19. Yayoi Kusama, New York, 1966

And then, Western designers, musicians and actors rediscovered the kimono, and began transforming it, manipulating it, making it their own. Among them, designers like John Galliano, Alexander McQueen (above, fig. 8) and Jean Paul Gaultier, (Figs. 20, 21) Pop stars like Björk, Freddie Mercury, David Bowie and Madonna. (Figs. 22, 23, 24) Apparently Alec Guinness agreed to join the Star Wars cast when he learned that his character, Obi-Wan Kenobi, would wear a kimono (Fig. 25).

Figure 20. John Galliano

Figure 21. Jean Paul Gaultier for Madonna

Figure 22. Bjork, Alexander McQueen, designer, photo by Nick Night

Figure 22a Kimono designed by Alexander McQueen worn by Björk (currently on exhibition at Palais Galleria)

Figure 23. Freddie Mercury

Figure 24. David Bowie

Figure 25. Kimono of Obi-Wan Kenobi

In the last 15 or so years, Japanese designers have become interested in kimonos again. Jackson attributes this revival to young Japanese who are bored with global fashion, who were looking for something different, something unique. And they found it at home. That, according to Jackson, was the impetus for the exhibition.

And what about the accusations that western designers and consumers are guilty of cultural appropriation? As Jackson says, "There is obviously quite a fine line between cultural appreciation and appropriation.” As she and her team gathered kimonos for the exhibition in Japan, they met young Japanese designers and asked them how they would feel about Westerners wearing their outfits. Far from being offended, they welcomed it because western consumers will insure that their industry survives," And it can only do that if it remains an item of fashion, (Figs. 26, 27) rather than a garment that is ‘revered and restricted’.

Figure 26. Rei Kawakuba for Comme des Garçons, 2018

Figure 27. Jotaro Saito, designer

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.