Villa as Madeleine

Villa of Delirium by Adrien Goetz

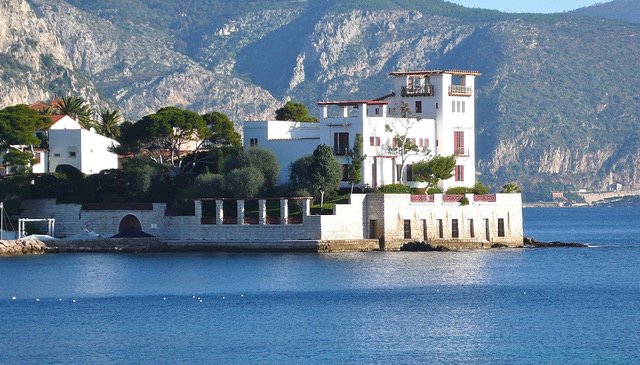

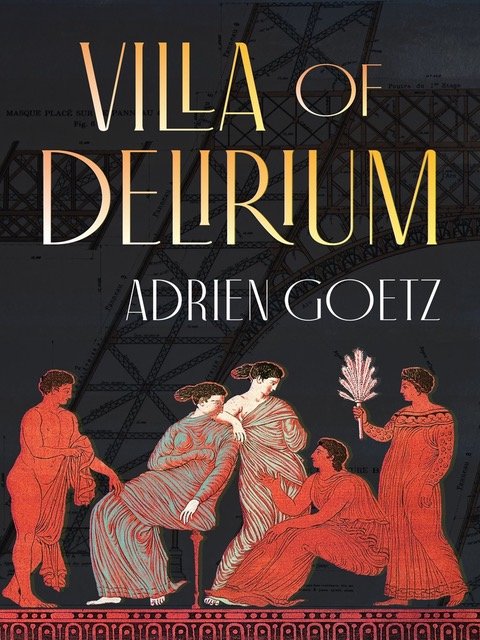

A few weeks ago, I wrote about two grand villas on the Côte d’Azur. One of them was a medieval pile. Neither the story of the owners nor the story of their villa interested me. The other property was different. Completely new, completely antique. The man and his house intrigued me. So when I learned of an historical novel about Theodore Reinach and the Villa Kerylos, (Figure 1) I was keen to read it. The Villa of Delirium was written by Adrien Goetz, in French, in 2017. (Figure 2) It was translated into English by Natasha Lehrer in 2020. I have not read the original French but I can tell you that the English translation is beautiful, graceful, elegant. After I finished reading the book, I couldn’t let it go. It haunted me. There was only one thing to do. Read it again. I enjoyed it even more the second time. It’s that kind of book.

Figure 1. Villa Kerylos, Beaulieu-sur-Mer

Figure 2. Villa of Delirium, Adrien Goetz

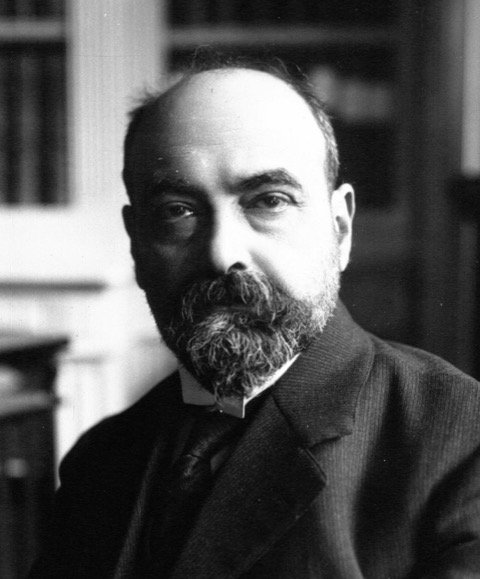

To remind you, Théodore Reinach (Figure 3) was, among other things, an archeologist, mathematician, lawyer, philologist, epigrapher, historian, numismatist and musicologist. But it is Reinach the Philhellene, the Grecophile, who interests us here. The man who had a Greek house built for himself and his family at Beaulieu-sur-Mer, on the Côte d’Azur, near Nice. (Figure 4) He bought the land at the suggestion of his friend, Gustave Eiffel, who had a home nearby. The site was perfect, the sea on three sides. His choice of architects was perfect, too. Emmanuel Pontremoli was just starting out. The winner of the Prix de Rome in Architecture, he had already done excavations at ancient sites. He brought both enthusiasm and experience to the task.

Figure 3. Theodore Reinach, 1913

Figure 4. Villa Kerylos, Terrace

Working together, Reinach and Pontremoli created a villa that an ancient Greek architect would have designed had he lived at the beginning of the 20th century. Their quest, a sort of What Would Jesus Do (a phrase which originated in the early 1900s as the villa was taking shape) substituting Greek Architect for Jesus, of course, informed the decisions they made. Many aspects of the villa are reminiscent of ancient Greek structures but many more confirm that this is a real house, not a play house. Begun in 1902, it was largely completed by 1908. The inspiration is classical but all the mod cons of the early 20th century are here, too - sous sol heating under the decorative mosaic floors, solid marble showers and baths with hot and cold running water.

Before I continue, I want to remind you again that this is an historical novel. Think Ragtime. Some of the people are fictitious - like the narrator and his beautiful Ariadne. And some of the events are, too. Did Theodore and Adolphe Reinach search for the tomb of Alexander the Great? I don’t know. Did they find a crown in one of the monasteries on Mt. Athos. I can’t confirm that either. But the Reinach family’s foes and woes are real. As are many of the events discussed. Like the Saitapharnes Tiara affair (more about that later).

The author has a keen sense of people and place, which he shares with us through the most poetic and poignant asides and digressions.

So, I hear you asking, again, what is the book about? Basically, it is about a man and the time he spent with members of the Reinach family, both at Villa Kerylos and elsewhere. His story is not linear. It is Stream of Consciousness. It is Proustian. We spend a lot of time with the narrator’s memories. And his memories provoke us to visit our own. Villa as Madeleine.

All of the action, such as it is, takes place during the course of a day. Which begins when we sneak into the Villa. Nothing illegal here, the narrator has a key. We walk through the front door. But he hasn’t told anybody he is coming. And he has chosen this day because none of the Reinach clan is in town and he is pretty sure that the Villa’s caretakers and other villagers will be away or preoccupied with the public festivities surrounding the wedding of Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier of Monaco.

The narrator has ostensibly come to look for something he believes belongs to him. And as he looks, he tells us about the house, about living in it. As the day wears on, we realize that he is here, for what he hopes will be the last time, not only to find what he believes belongs to him, but to relive his memories of this villa, of these rooms. And to try to free himself of their hold on him.

The author doles out facts parsimoniously. But sometimes we can piece things together ourselves. For example, the narrator doesn’t tell us his age until the end of the book. But we can figure it out sooner. Halfway through the book, we learn that he was born in 1887. A quick Google check and we have the date of Grace Kelly’s wedding to Prince Rainier - April, 1956. So our narrator is nearing his 70th birthday.

One thing we learn right away is the narrator’s name, Achilles. Very convenient for a story about a villa inspired by ancient Greece. But it is the name his parents, Greek immigrants, gave him. Achilles’ mother is Gustave Eiffel’s cook. Eiffel sees right away that Achilles can draw and he provides the boy with drawing paper and pencils.

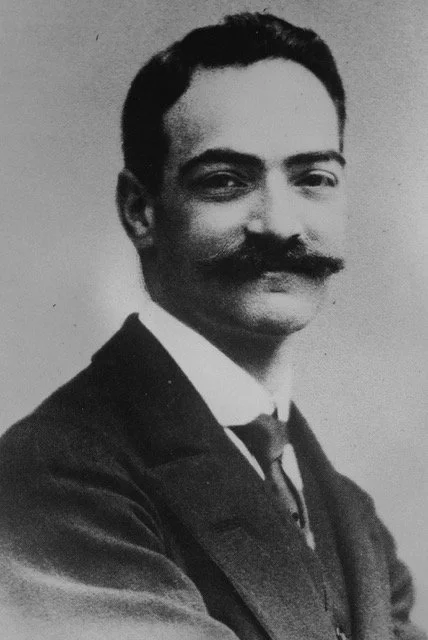

It is at Eiffel’s home that Theodore Reinach first meets Achilles. Reinach also sees how facile the boy is with pen and paper. On a whim, he entrusts Achilles with sending him weekly sketches of the villa as it takes shape. For the next 6 years, from 1902 to 1908, as he passes through his teen years, Achilles becomes as familiar with the villa as the architect, the owner, the builders and the craftsmen. And when Theodore is around, Achilles becomes something of an experiment. Reinach teaches Achilles ancient Greek. And Achilles becomes the companion of Adolphe Reinach, (Figure 5) Theodore’s nephew. Who is the same age as Achilles.

Figure 5. Adolphe Reinach, 1910

The narrator’s references and insights range from the classical to the contemporary, from archeological digs to anti-semitic ones. But you won’t be drowning in facts. You will catch some references and you will be very pleased with yourself. Some insights you won’t notice, and that will be okay, too. Others will intrigue you enough to do a little research. Like I said, this is a seriously wonderful book.

As we move from room to room, the narrator identifies the scenes depicted on the mosaic floors and frescoed walls. (Figures 6, 7) Exploits of Greek gods and goddesses. Scenes from the Trojan War. As an art historian, I know these scenes, artists have depicted them for centuries. But my knowledge was superficial until I began homeschooling my son. The movie Troy came out when he was 10 and he became obsessed with the Iliad and Odyssey. We began with children’s versions before tackling translations of Homer’s texts. We visited museums in search of depictions of scenes on kraters and kylixes and amphorae. Eventually Nicolas moved on - to Sparta. So when the narrator described Theodore Reinach as looking as if a fox was eating his entrails, I recognized the reference. Nicolas may have moved on, but I didn’t. I found a book by Madeline Miller, about Achilles and Patroclus and the Centaur Chiron. Called The Song of Achilles, it is a beautiful book.

Figure 6. Labyrinth design, Mosaic floor, Stateroom, Villa Kerylos

Figure 7. Theseus killing the Minotaur, detail, Labyrinth, Mosaic floor, Villa Kerylos

As the narrator describes his relationship with Adolphe, Theodore’s nephew, we think, as we are surely meant to, of Achilles and Patroclus. (Figure 8) When Patroclus fell in battle, Achilles retrieved his friend’s dead body and vowed revenge. When Adolphe is killed early during the Great War, our narrator, Achilles also vows revenge. But he must leave Adolphe where he fell, where he died. To fight, to kill, to be wounded and to fight again. His failure to keep his best friend safe, to bring his body home to his family, haunts him. And then, irony of ironies. Adolphe died at 25, in 1914. Leaving his wife a pregnant widow. History grimly repeated itself 25 years later, when their son died in battle, during the next war.

Figure 8. Achilles binding Patroclus’ wounds, Kylie 500 B.C.E.

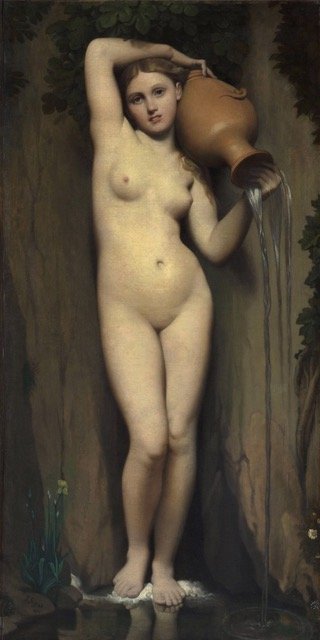

Much of the hold the villa has on Achilles after the war revolves around Ariadne, the wife of the architect’s chief assistant. They become lovers as Achilles recuperates from his war wounds. They make love in every room and spend long moments in the various luxurious baths. (Figures 9, 10) Achilles describes Ariadne referencing paintings that I know so well. Ingres’ Bathers and The Source. (Figures 11, 12) Fragonard’s couple in The Bolt. (Figure 13) He tells us that Ariadne arrived one day dressed in Fortuny, (Figure 14) resembling the Charioteer of Delphi. (Figure 15). My pleasure in reading the description was enhanced because I had just visited the Fortuny Museum in Venice a few weeks earlier. And then Ariadne disappears. It was 1920. Desperate, Achilles goes to her husband’s office. Who tells Achilles that Ariadne has abandoned him, too. Their Ariadne is not the maiden Theseus deserted on the island of Naxos after she helped him slay the Minotaur. (Figure 16) This Ariadne is the deserter, not the deserted. Achilles eventually marries, has children, then grandchildren. But it is his true love, his Ariadne, who haunts him and these pages.

Figure 9. Bedroom, Villa Kerylos

Figure 10. Bathroom, Villa Kerylos

Figure 11. The Valpinçon Bather, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1808

Figure 12, The Source, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1820+

Figure 13, The Bolt, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1777

Figure. 14. Delphos Dress, Mariano Fortuny, 1909

Figure 15. Charioteer of Delphi, Pythagoras, 470 B.C.E.

Figure 16. Ariadne Abandoned by Theseus on Naxos, John Vanderlyn, 1809-14. Painted in Europe, it was a scandal when it was shown in America, eventually covered by a cloth

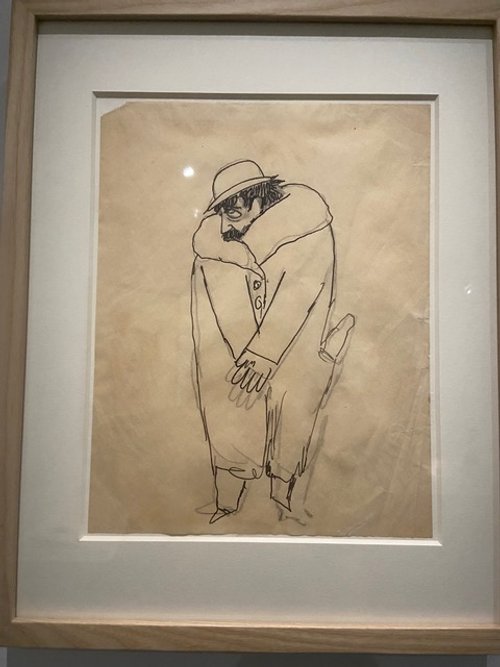

In my review of the Villa, I posited that the three Reinach brothers published books about historical moments of anti-semitism because of their involvement with the Dreyfus Affair. But it wasn’t that. They were responding to the rabid anti-semitism that swirled around them. Mostly concentrated on the Tiara of Saitaphernes, (Figure 17) They had vouched for its authenticity. They had donated funds to the Louvre for its purchase. Everyone went to see it. Even Proust. Achilles imagines that he arrived wearing his heavy overcoat. Here’s a caricature of Proust wearing that coat (Figure 18). And then the tiara was found to be a modern fake. And somehow the Reinachs were implicated in the country’s humiliation. Anti-semitic ridicule rained down upon them.

Figure 17. Tiara of Saitaphernes

Figure 18. Proust in his overcoat with a bottle of water in the pocket

Reinach, family of woe. We read about another painful irony. Leon, Theodore’s son, a gifted musician, was deported to Auschwitz and murdered in 1942. That same year, the son of the classicist Wilheim Furtwängler, the Reinach’s most vociferous critic, conducted a concert for wounded German soldiers to mark Hitler’s birthday.

The Reinach brothers couldn’t understand why, even though they were smarter than everyone else, they hadn’t discovered anything. Which prompted Theodore to search for the tomb of Alexander the Great. Maybe. Achilles describes Theodore Reinach’s visit to Arthur Evans reconstruction at Knossos. A reconstruction that didn’t depend upon facts or evidence. I know that site, I smiled at the comment.

How whimsical it was for me when the narrator mentioned the fragment of the Parthenon frieze at the Louvre. (Figure 19) Ginevra and I had seen it days earlier. And talked about the procession of girls bringing the peplos to Athena.

Figure 19. Fragment of the Parthenon Frieze, Louvre

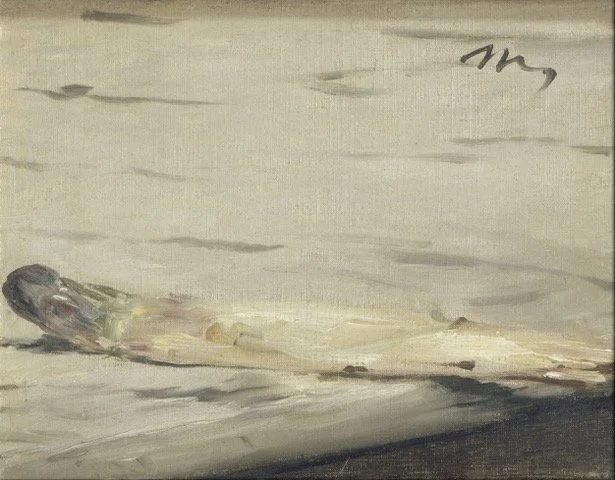

When Achilles talks about Fanny, Theodore’s wife, he tells us that she is the niece of Charles Ephrussi, the collector of Manet’s asparagus. (Figures 20, 21) We know exactly what he means because Proust wrote about those asparagus spears, too.

Figure 20. Bundle of Asparagus, Edouard Manet, 1880

Figure 21. Asparagus Spear, Edouard Manet, 1880, given to Charles Ephrussi because he overpaid for the bundle of asparagus

Here’s one last evocation of time and place. After the Nazis trashed Kerylos, the Dairywoman’s daughter alerts Achilles. Who tells us that she was “a beauty who was going to find herself facing a lot of problems after the Liberation” And we know exactly what he means. She was going to be accused of consorting with the enemy, of having a German lover. She would pay for her transgressions by being stripped naked, having her head shaved and then being paraded through town with other similarly stripped and shorn women. A fate Coco Chanel richly deserved but managed to avoid.

And finally, (promise) two comments Theodore shared with Achilles which defined Theodore’s philosophy of life and which came to define Achilles own:

“It is precisely with what serves no purpose that one achieves great things.”

AND

“I do not ask that an honest man speak Latin only that he has forgotten it.”

Perfect, right? So is this book.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.