Your worst enemy is (your) poor taste

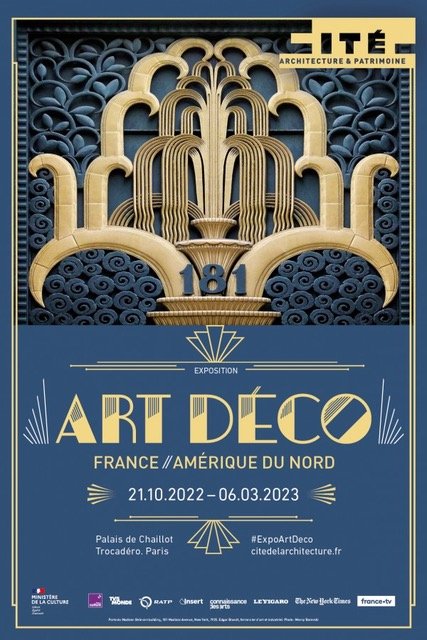

‘Art Deco France Amérique du Nord’ Cité de l’architecture et du Patrimoine

The exhibition called Art Deco France Amerique du Nord is not the first time this museum has mounted an exhibition on Art Deco. Nearly a decade ago, there was an exhibition called ‘When art deco seduced the world” which focused on the 1925 International Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, which gave the Art Deco movement its name. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. "1925 When Art Deco Seduced the World,” Cité de l’architecture et du Patrimoine, poster

That exhibition must have been dizzying. Here’s the scenario I’m imagining that got to this second exhibition about the same subject. The curators and researchers had a ton of stuff they couldn’t stuff into that exhibition. So much stuff that they probably started envisioning an Art Deco Part 2, just to keep their spirits up. And while any number of exhibitions might have come about from all that stuff, one geographical location stood out - North America. Et voila!

Although still called Art Deco, this exhibition does not begin as the previous one did, with the 1925 exposition because the story of Franco-American cultural exchange begins much earlier, indeed a century and a half earlier when Lafayette came to America and made that country’s fight for freedom his own. (Figure 2) This exhibition also traces cultural connections beyond architecture and design going as far afield as aviation (you may find the American Indian logo adopted by the aviators offensive now) and boxing and that perennial contact sport - marriage! (Figures 3, 4)

Figure 2. George Washington with Marquis de Lafayette

Figure 3. American Members of the Lafayette Escadrille, World War I pilots

Figure 4. American aviators all had profile of an American Indian on the plane

The exhibition begins in the corridor. As you wait to enter, your eyes feast on a row of Buy Liberty Bond posters, each different, each featuring the Statue of Liberty (which was designed by the French sculptor, Frederic Bartholdi and presented by France to America on America’s 100th birthday). All of the posters admonish Americans to buy bonds, to support the war effort. (Figures 5, 6)

Figure 5. Liberty Bond poster

Figure 6. Liberty Bond poster

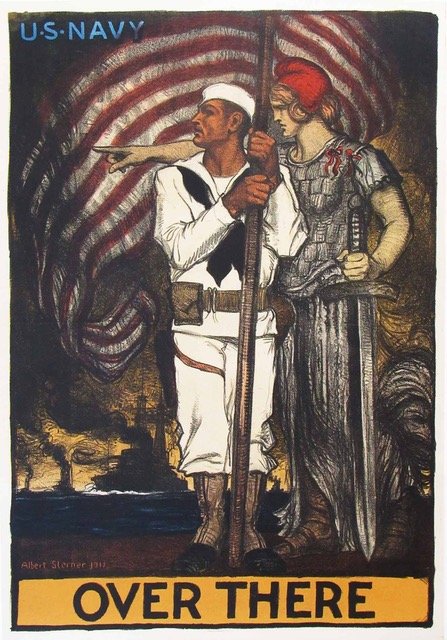

Immediately upon entering the space, two sturdy Art Deco figures - America and France - stand united. These are studies for a statue of friendship that was never built (Figures 7, 8) Nearby is a copy of the 1791 city plan of Washington, D.C. by the French military engineer, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, which was built. (Figure 9) And around the corner, Enrico Caruso singing “Over There,” George M. Cohan’s 1917 song written to encourage young American men to enlist in the army and go ‘over there’ and fight the Germans. (Figure 10)

Figure 7. Model for Statue to Franco-American friendship (never built)

Figure 8. Pax statue never built

Figure 9. Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s plan for the Federal City, aka Washington, D.C. 1791

Figure 10. France pointing the way ‘Over There’

The earlier exhibition on Art Deco celebrated French buildings, like the 1928 Hôtel Plaza in Biarritz and Carnegie Library in Reims (Figure 11) When I saw this library in Reims, it was after a few champagne tastings and I thought I had surely read the sign wrong! This time French buildings are joined by American ones like Rockefeller Center (1931) which is documented with an exuberant display of plaster casts and bas reliefs that we all recognize and admire, among them Elegance. (Figure 12)

Figure 11. Carnegie Bibliothèque in Reims, 1928

Figure 12. Part of the decoration of Rockefeller Center celebrating Franco-American Friendship

Rather than French department stores like La Samaritaine, (which has been restored and which you must visit when you are here), we are treated to drawings and photographs of equally elegant department stores that popped up all over the United States, like Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, Gimbel Brothers in New York and Marshall Field in Chicago. Art Deco inspired objects and clothing were sold in those stores, whose interiors were themselves Art Deco stage sets. (Figures 13, 14, 15).

Figure 13. Marshall Field Department Store

Figure 14. Department Store

Figure 15. Wanamaker Department Store

The earlier exhibition had celebrated working women who made Art Deco their own - from the architect Charlotte Perriand to the dress designer Coco Chanel; from the dancer Josephine Baker to the actress Louise Brooks. The exhibition this time includes Coco Chanel and Josephine Baker (Figure 16) but mostly focuses on wealthy American heiresses like Barbara Hutton (Figure 17) and Peggy Guggenheim (Figure 18) And women who ran fashion magazines, like Vogue’s Diana Vreeland.

Figure 16. Josephine Baker on stage in Paris

Figure 17. Barbara Hutton

Figure 18. Peggy Guggenheim

The contributions and conquests of all these women were familiar to me, but many fascinating aspects of Franco-American cooperation were new.

For example, after the Great War ended and while American soldiers waited for transport back home, a group of American artists decided to open an art school for these “sammies” (the sons [nephews?] of Uncle Sam). The American Expeditionary Forces Art Training Center opened in March 1919, in Meudon, near Paris, in the former home of the dancer, Isadora Duncan. The mostly North American teaching staff was joined by French artists. Among them the architect Jacques Carlu (whose American career would include a decade teaching architecture at MIT) and the painter Jacques-Emile Blanche (whose iconic portrait of Proust was everywhere last year).

Four years later, in 1923, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts began teaching painting, sculpture and architecture. Every year, 70 U.S. students lived and learned at that elegant chateau, Napoleon’s final French residence. The architect Jacques Carlu also taught there and was joined by professional decorators and muralists. They still come, although now it is architecture only that is taught.

A music academy was already at Fontainebleau when the artists arrived. Its history began when the war did. General Pershing, lamenting the poor quality of the U.S. army’s military band, brought the conductor of the New York Philharmonic to France to organize a school in Chaumont, where the US troops were headquartered. In 1921, the school moved to Fontainebleau where its mission, to offer the best of French musical education to young, promising musicians, continues to this day.

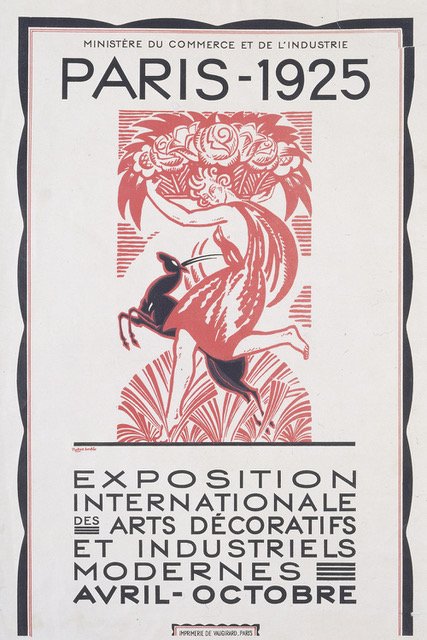

Although not the only focus of this exhibition, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which opened in Paris on 28 April 1925 and which gave rise to the Art Deco style, is certainly celebrated. (Figure 19) During its six month run, nearly sixteen million people visited. The New York Times wrote article after article extolling it. American and Canadian architects, many of whom had trained at l'Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris or l'Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau, visited it. And a virtual army of American manufacturers were sent to the fair by Herbert Hoover who was, at the time, America’s Secretary of Commerce.

Figure 19. Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderne, Paris 1925

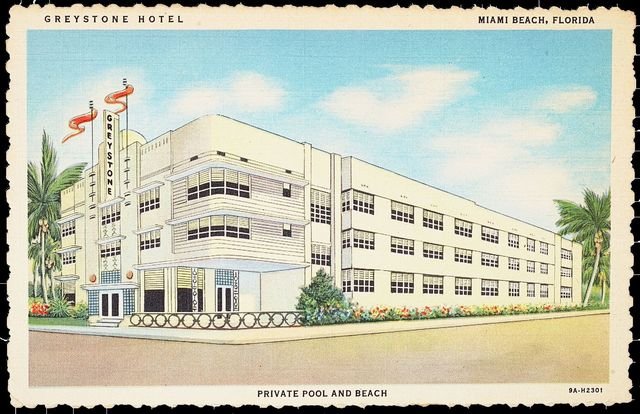

There are examples of Art Deco all over the United States but Art Deco seems to have been made for Miami. In 1926, Miami was leveled by a hurricane. It had to be rebuilt. By necessity, Tropical Deco, a simplified version of Art Deco, was born. The style dominated both residential and commercial structures. But the style most perfectly suited apartments and hotels. These buildings, from 4 to 6 stories high, were capped by roof terraces and shaded by curved framing. The facades often had a central concrete column emblazoned with the building’s name. Many architects, both French and American born and French trained, made names for themselves with those buildings that have given Miami its distinctive look for nearly a century. Buildings built of necessity, now celebrated as landmarks.(Figures 20, 21)

Figure 20. Greystone Hotel, Miami Beach, Florida

Figure 21. Carlisle Hotel, Miami, Florida

French designers were everywhere in the United States. In Hollywood, where Paul Iribe was commissioned to design stage sets for films. And on both sides of the continent, wealthy Americans commissioned French and French trained designers to update the interiors of their mansions. French illustrators also designed the covers of fashion magazines like Harpers and Vogue, too. (Figure 22).

Figure 22 Vogue Magazine Cover, Art Deco style

For anyone whose plans hadn’t permitted a visit to the 1925 Paris Exposition, there were two ocean liners to experience, the Ile-de-France and the Normandie, so-called “floating Art Deco showcases”. Photos of the interiors and objects from them, give us a sense of the luxe of those trans-Atlantic liners. (Figures 23, 24)

Figure 23. The Grande Salon of the Normandie ocean liner

Figure 24. Decoration from Normandie ocean liner

The exhibition has a few photographs of Canadian Art Deco buildings, but it gives an entire room over to the murals which decorated the Mexican Ambassador’s Residence in Paris. I wasn’t expecting to see murals like this here, but after seeing an exhibition on Diego Rivera in San Francisco and another on Frida Kahlo in Paris, they looked just right. The murals were painted in 1928 by the Mexican artist, Angel Zárraga. They represent the history of Mexico, its relationship to the United States and its affection for and friendship with France. As one writer noted, Zárraga imbued his murals with patriotism and a mysticism rooted in Mexican folklore. (Figures 25, 26, 27)

Figure 25. Mexican Ambassador’s Residence, Paris, France, paintings by Angel Zárraga

Figure 26. Allegorical figure of Mexico looking north, Mexican Ambasssador’s Residence, Paris, Zárraga

Figure 27. Allegorical figure of France, Mexican Ambassador’s Residence, Paris, Zárraga

There are photographs of Manhattan skyscrapers (gratte-ciel), like the 1928 Chrysler Building, designed by the American architect William Van Alen, who had studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. And the Empire State Building, which began construction two years later, a year after the Crash. (Figure 28) While most construction ground to a halt, the Empire State Building was completed in a little over a year. Profits were a little slower coming, that didn’t happen until the 1950s.

Figure 28 Skyscraper with Notre Dame de Paris superimposed

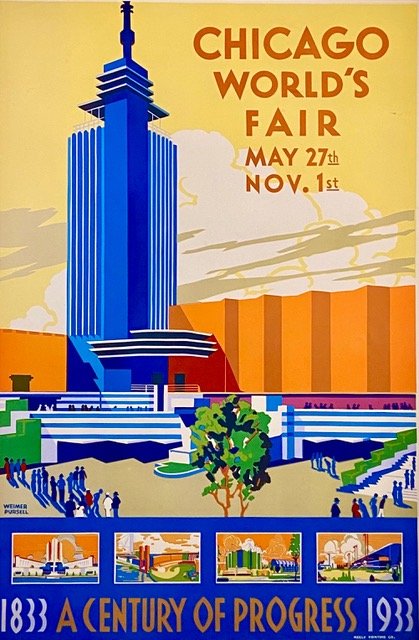

The beginning of the Great Depression saw a pause in American consumption of luxury items imported from France. But people still needed ‘things’. So things just got simpler as designers began focusing on mass produced consumer items. The 1933 Chicago exhibition called A Century of Progress (Figure 29) celebrated these useful, everyday objects. This exhibition highlights a dizzying array of items - from telephones to toasters, microphones to mixers. The style wasn’t Art Deco anymore, it was Streamline Moderne, a sleeker variant, inspired by aerodynamic design. Which, for a car or airplane, allows for faster, more efficient travel. And for objects those curving forms and long horizontal lines were considered modern by association. (Figures 30, 31)

Figure 29. A Century of Progress, Chicago World Fair, 1933

Figure 30. Streamline Moderne products

Figure 31. More Streamline Moderne products

In 1934, the French architect Jacques Carlu, former MIT professor of architecture and the so-called ‘ambassador for Streamline Moderne,’ couldn’t find a job. So, he returned to Paris where he was commissioned to design what is considered to be his most famous building, the Palais de Chaillot, for the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne. The commission was a complicated one, to replace the 1878 Neo-Byzantine-inspired building and get rid of the parts of it that obstructed the view. Drawing on his own past projects in North America and influenced by the Brobdingnagian sized government buildings in Washington, D.C. Carlu’s plans for the Palais de Chaillot consisted of a huge main building with two long, raised pavilions set on a grande esplanade. There is a model of Carlu’s building project in this exhibition. (Figure 32) It is the building in which this exhibition was held. We always read about the influence of French buildings on American designers and here we learn about a French designer who brought French design to America and whose subsequent work in France was inspired by buildings in America! And it still offers the best views of the Tour Eiffel! (Figure 33)

Figure 32. Model of Carlu’s plan for the Palais de Chaillot

Figure 33. View of the Tour Eiffel from Cité de l’architecture et patrimoine, Paris

The exhibition reinforced what I suspect we already know - American knowhow succeeds when it is mixed with French taste. The French, like the ancient Greeks, are the artists. The Americans, like the ancient Romans, are the engineers. The Americans invented the skyscraper, the French made the gratte-ciel art.

A FEW QUOTES TO KEEP YOU THINKING:

“The skyscrapers of New York City and Chicago have nothing in common with modern French architecture, and yet they are the work of former students of our Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.” Historian Louis Réau

“The gigantic American buildings, whose beauty cannot be denied, were first born on the Left Bank of the Seine from 1890 to 1910.” Aviator Gabriel Voisin

“I have more to learn from the skyscrapers, from Broadway lit up at night, and from the bustle of New York City than from Place Vendôme in Paris … (but) I think your worst enemy is poor taste… You have created everything except taste…” Illustrator Paul Iribe

“(T)his 'new style' (Art Deco) with its simple and fluid lines embodied the social and technical revolutions of the beginning of the century, such as the speed of cars, ocean liners or planes. It was the spirit of the times," Emmanuel Bréon, Curator.

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.