After the Highlands, the Lowlands beckoned

A few days in Glasgow

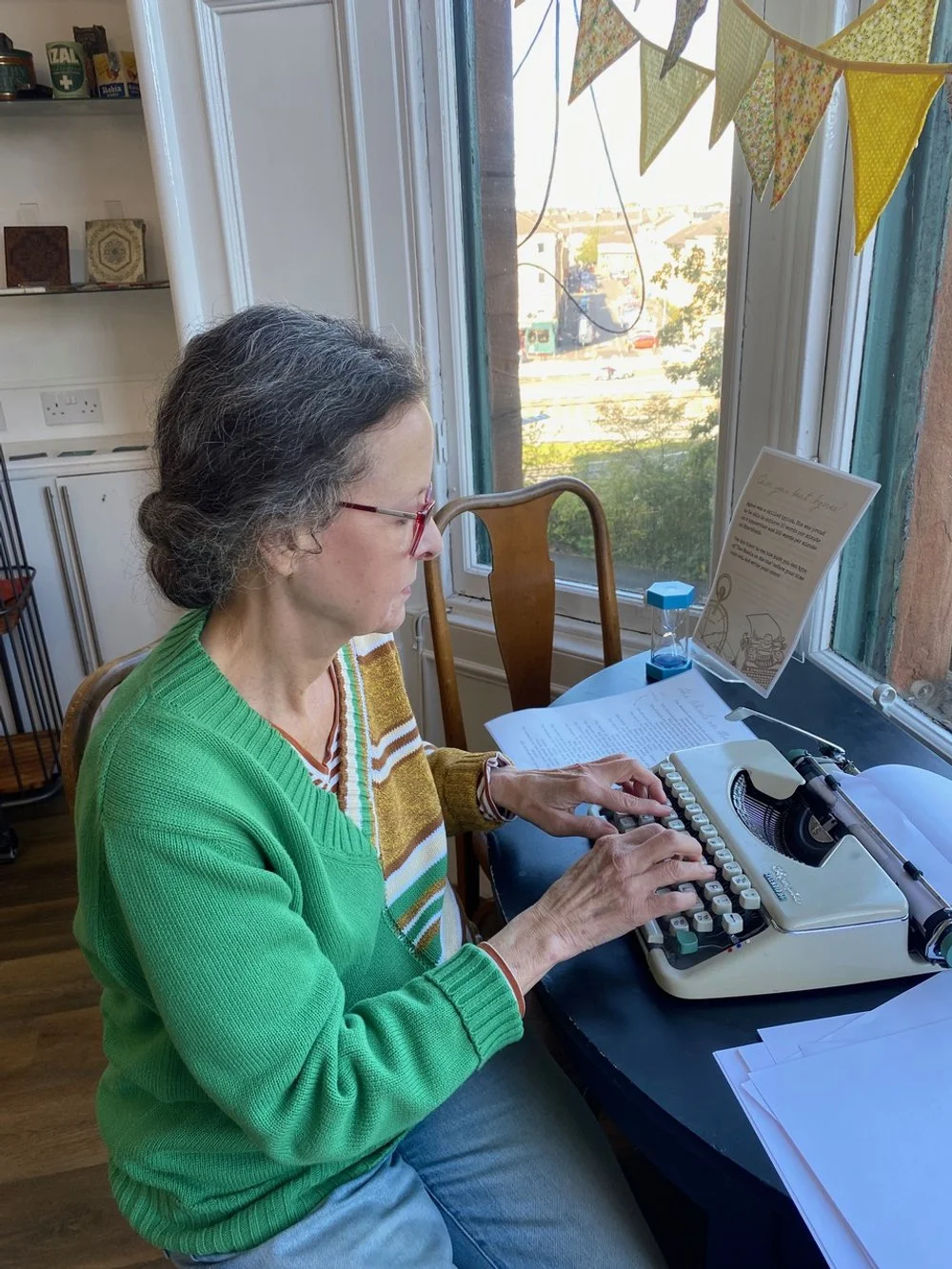

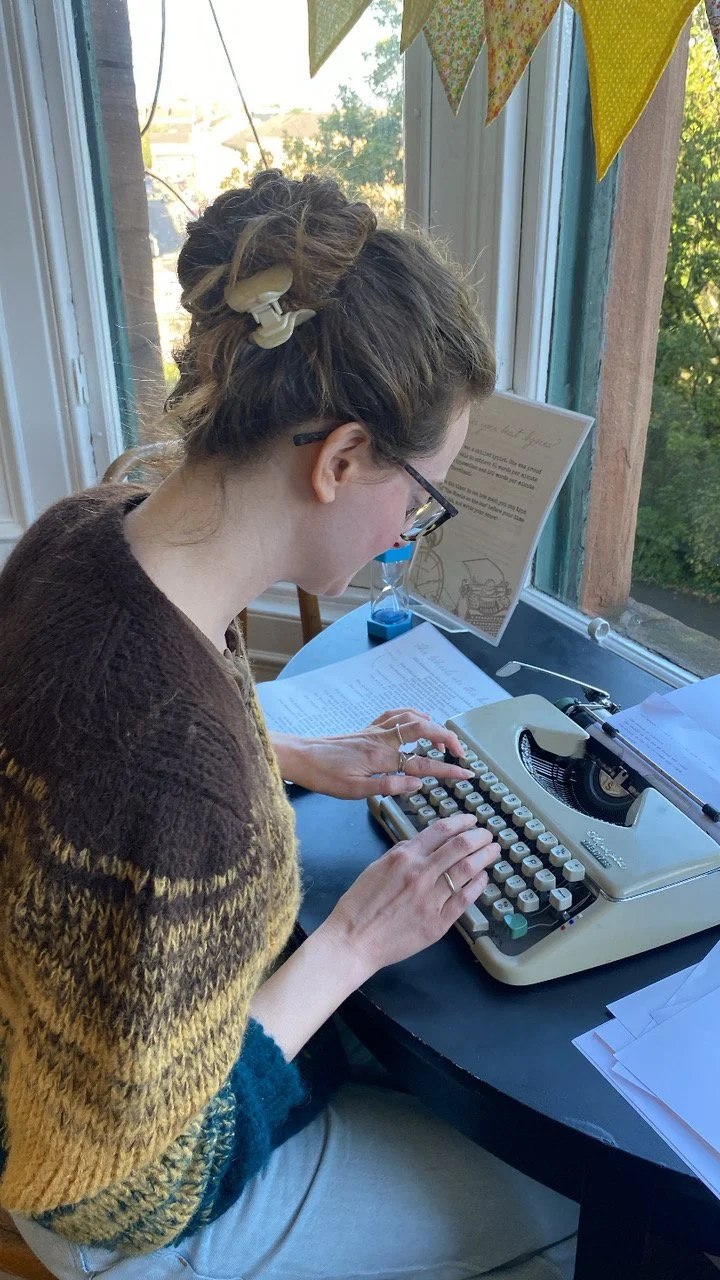

Typing in the Tenement House, Glasgow

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. I’ve been running around a lot since I got back from Scotland and I can’t wait to tell you about what I’ve been seeing. Like the Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely exhibition at the Grand Palais. Which I loved so much that I needed to see more than their wonderful Stravinsky Fountain across from the Centre Pompidou. So it was off to Milly la Forêt to see their Cyclops and while I was there, to see Jean Cocteau’s house and the tiny church he decorated and in which he is buried. Another day, Ginevra and I went to the Musée d’Orsay to see the John Singer Sargent show, crowded but good. We saw an excellent exhibition at the Orangerie on the gallerist Berthe Weill. The Georges de la Tour exhibition at the Jacquemart-Andre was beautiful. The exhibition on Sleep at the Musée Marmottan-Monet was anything but fatiguing.The exhibition at the Musée d’Art Decoratif on the fashion designer Paul Poiret was much richer than we expected. We had tickets for the Jacques Louis David exhibition at the Louvre for the day after Empress Eugenie’s jewels were stolen. But the museum was closed. So we paid our respects to some old friends at the Père Lachaise Cemetery instead. More about all that in upcoming posts.

Today, we’re in Glasgow, Scotland’s second city. We stayed one night before we began our walking adventure in the Highlands and two nights after it. At two different hotels, both recommended by Rick Steves, both in Glasgow’s cool ‘hood, Finnieston, about which Sam Hueghen, star of Outlander, wrote in the New York Times.

so much typing to do!

After 7 hours on two different trains, from Paris to Glasgow, Ginevra refused to jump on a bus or grab a taxi to get to our hotel. So we walked, 35 minutes in the rain and the wind. Excellent preparation for the West Highland Way. Once we got to the hotel, we clomped up 10 steps to the Reception. Where we learned that guest rooms were on the demi sous-sol. I use the French word because it sounds a lot better than the English word for hotel rooms half above and half below ground level - basement. Alas, there was no elevator. We thumped, thumped, thumped our luggage down to our room, which was in the front. When we opened the drapes, we could see people milling about and walking by. To be more precise, we could see them from their knees down. Both hotels in Glasgow were like this. The thumping down to our rooms with our luggage was not easy, the clomping back up with the luggage was worse. (Figs 1-3)

Figure 1. One of the many embellished Glasgow facades, a little dirty but very decorative

Figure 2. Another facade, the upper levels of which are beautiful, the street level - best not to notice!

Figure 3. One of the hotels where we stayed, you can see our room if you look down

On our day in Glasgow before our adventure, we wandered around the Botanic Gardens. There are lots of gently climbing and descending paths. I hoped the paths of the Way would be as gentle. Alas, you don’t always get what you want. The most fun part of the Garden was the Kibble Palace, a late 19th-century wrought and cast-iron glasshouse built for John Kibble, who didn’t live in the Botanic Garden. The glasshouse had to be dismantled and transported to the Garden on a barge along the River Clyde, the river that runs through Glasgow. The Greenhouse’s collection now includes orchids, carnivorous plants and tree ferns. And an eclectic assortment of statues. Like King Robert of Sicily from a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and statues of Old Testament figures like Eve, Cain, Ruth as well as an Elf and a Nubian Slave. (Figs 4-7)

Figure 4. Kibble Palace, Glasgow Botanic Gardens

Figure 5. Planting beds Glasgow Botanic Gardens

Figure 6. King Robert of Sicily from a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Kibble Greenhouse

Figure 7. Ferns and Eve, Kibble Greenhouse

Figure 7a. Eve’s cheeky bum

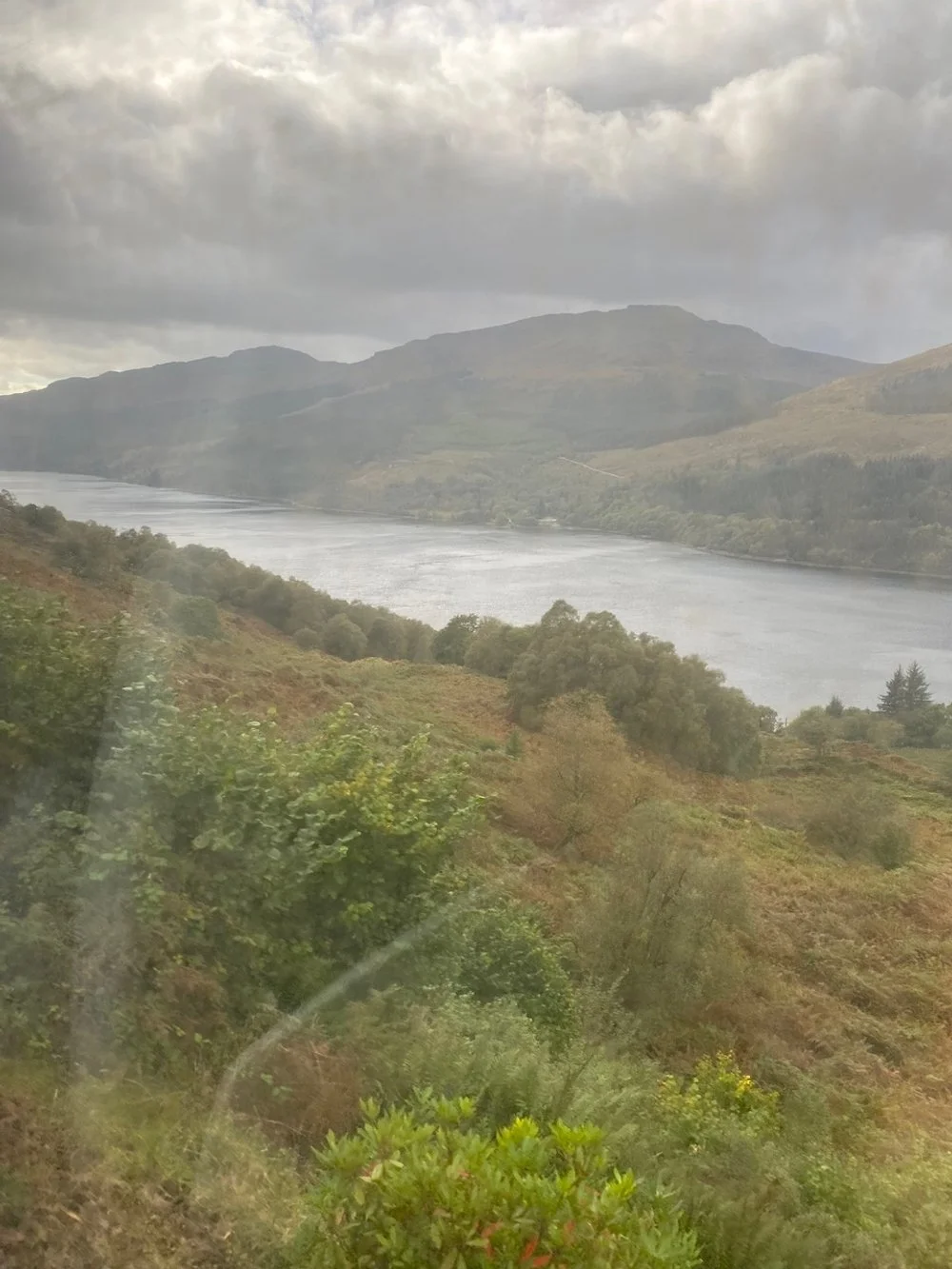

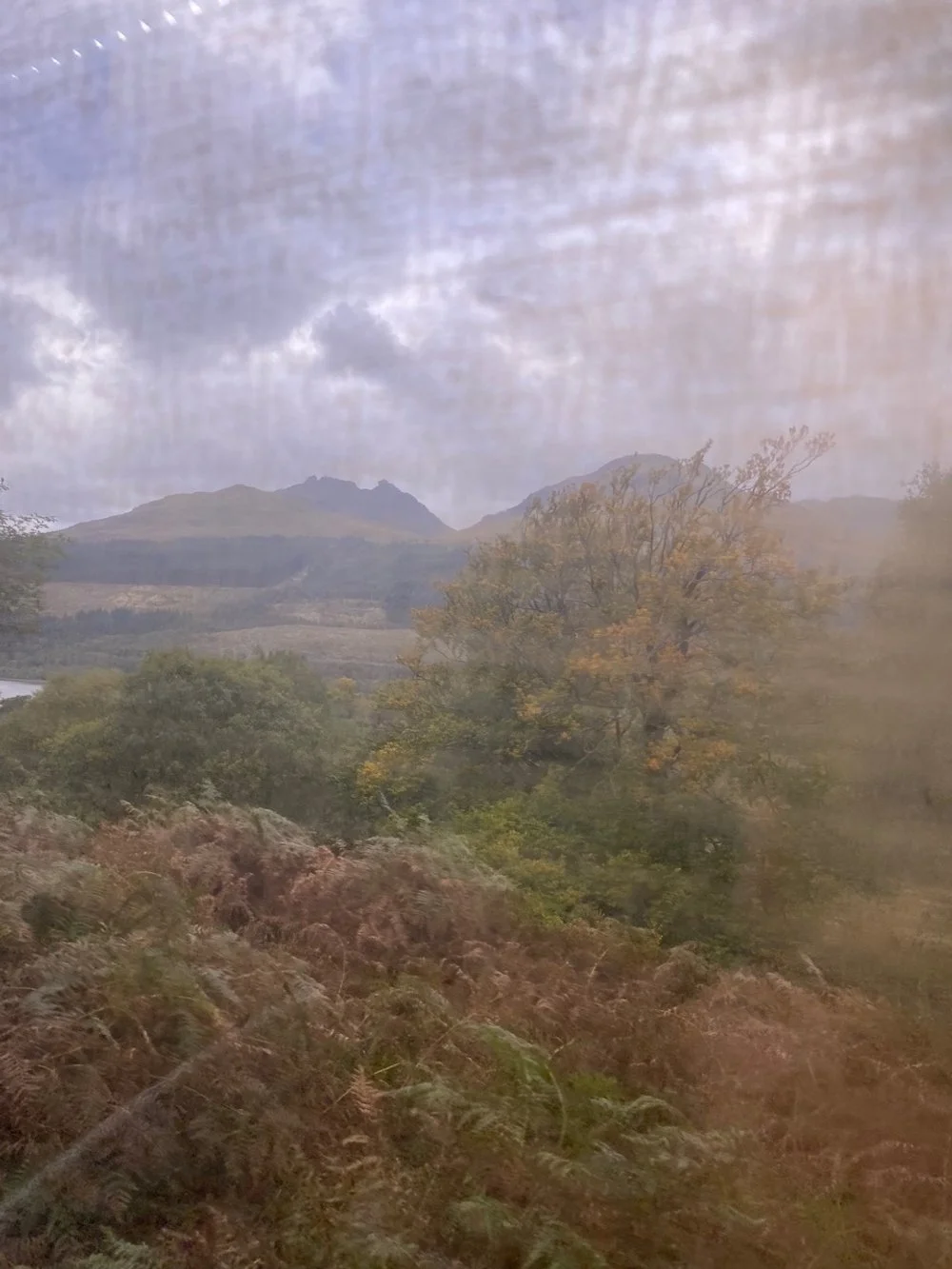

We returned to Glasgow by train for a couple nights after we walked the Way. We retraced our 9 day walk in four hours. It was a mad dash to get onto the train because the seats are not reserved and because both Ginevra and I suffer from motion sickness and need to be facing the same direction the train is going. Ginevra has another method for avoiding motion sickness, sleeping. I kept nudging her to look at the scenery. She kept mumbling, I already saw this, while we were walking, while you were hunched over your poles trying not to fall. (Figs 8-10)

Figure 8. Ginevra sleeping on train from Fort William to Glasgow

Figure 9. View from the window of the train from Fort William to Glasgow

Figure 10. View from the window of the train from Fort William to Glasgow

We packed a lot into the two days we were in Glasgow. Happily everything we wanted to see was close to our hotel. Among the highlights, the Tenement House Museum where we learned about Scottish life at the beginning of the 20th century and the Macintosh House, a celebration of the art & architecture of Charles Rennie Macintosh.

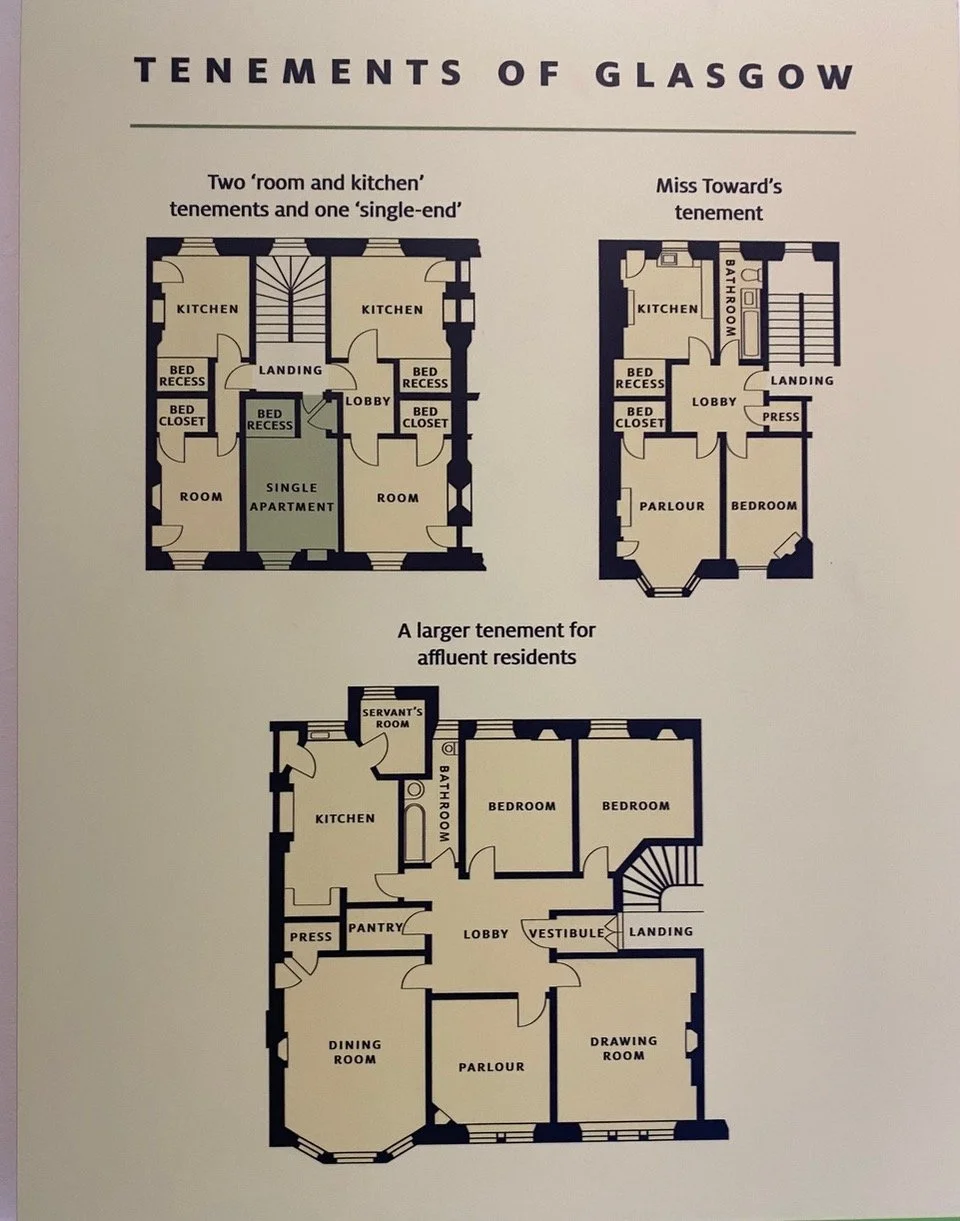

At the Tenement House Museum ((which Eugene Levy visited when he was in Glasgow for his travel show) we learned that our definition of Tenement - crowded, substandard housing for the poor, is not universal. In Scotland, its meaning is closer to what we call apartment buildings. Although not all tenements are equal. There were working class tenements - some with only one room, called a ‘single-end,’ essentially a kitchen with a recessed bed and some with two rooms, called a 'room and kitchen.’ Overcrowding was common, water and sewage facilities were poor. A single room could be shared by as many as 8 people and as many as 30 residents of a tenement might share a toilet. I guess that’s not so far from our definition of tenement. Middle class tenements were much bigger, with a salon, bedroom, kitchen and bathroom. Tenements for the wealthy were bigger still, with five or more rooms.

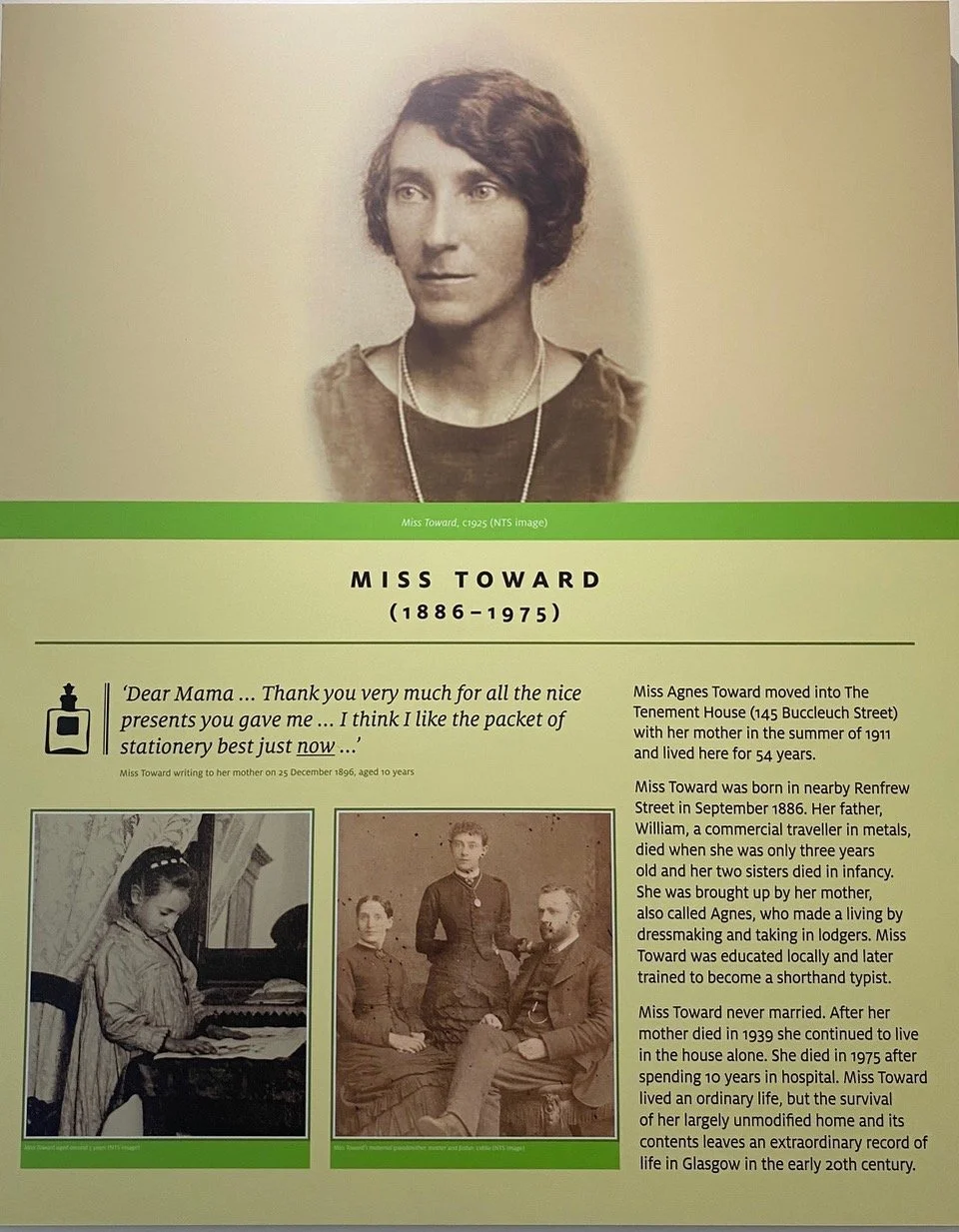

The apartment we visited was a time capsule. The four rooms of the apartment, meticulously restored, give an idea of middle class life in early 20th-century Glasgow. The apartment’s owner, Miss Agnes Toward, moved into the apartment with her mother in 1911, when she was 3, following the deaths of her father and baby sisters. Her mother worked as a dressmaker and took in borders. Agnes Toward, who never married, worked as a shorthand typist. After her mother died in 1939, Agnes lived in the apartment alone until 1965 when she moved to a nursing home where she died 10 years later.

“Miss Toward lived an ordinary life, but the survival of her largely unmodified home and its contents leaves an extraordinary record of life in Glasgow in the early 20th century.” She wasn’t a hoarder exactly, but she doesn’t seem to have thrown much out, either. I guess the take-away is that if you keep enough stuff long enough, said stuff becomes a time capsule. The curators used the evidence of Agnes’ stuff to illuminate the experiences of an ‘independent woman’ during the first half of the 20th century. In Miss Toward's day, few professions were open to women. Teaching and nursing weren’t available to everyone because they typically involved expensive training. But, in the late 1880s, Glasgow experienced a period of rapid commercial expansion. Simultaneously, the kinds of jobs available to women expanded. Because, typewriters. According to the exhibition curators, typewriting was compared to piano playing and therefore was considered suitable for a woman's abilities and presumably her smaller fingers. But whether teacher or typist, a woman was expected to stop working ‘outside the home’ once she got married. An idea which seems to be coming back in fashion in the U.S.A.

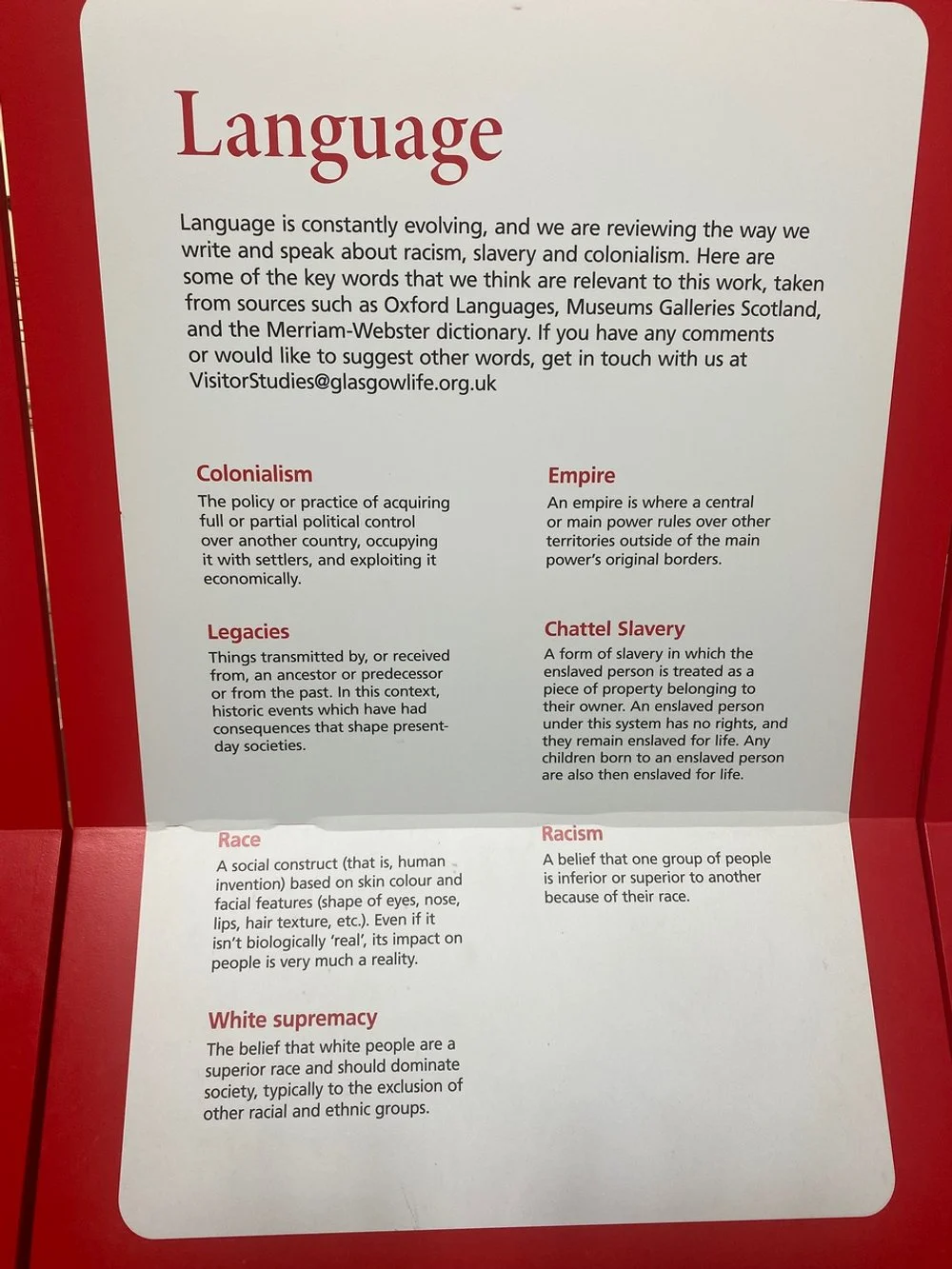

There was an unopened box amongst Miss Toward effects. Here’s what we can learn from it. During WWI, field nurses discovered that cellucotton (a cellulose substitute for cotton) used in surgical dressing and bandages was very absorbent. They began to use them as disposable sanitary pads. Soon afterwards an enterprising manufacturer began producing disposable sanitary pads, to be worn with belts or pinned into place. The price was prohibitive, about 7 times the price of today’s sanitary products (which are not cheap). Most women continued to use their own washable pads until well into the 20th century. “Did Miss Toward buy this product for travel, as suggested on the box? Most probably, as we know that (she) holidayed on the Scottish coast each year… This unopened box … reminds us that many people are still fighting for affordable sanitary products.” Which leads me to mention two things we saw everywhere in Scotland. The first is that women’s public toilets had free sanitary products. The second is that almost everything prompted a civics lesson, certainly in museums where references to colonization, racism and sexism were frequent. (Figs 11-19)

Figure 11. Tenement House where Tenement House Museum is located, Glasgow

Figure 12. Various configurations of apartments for poor, middle class and wealthy occupants

Figure 13. Miss Agnes Toward, the woman who lived in the apartment

Figure 14. Miss Toward’s Living Room with Fireplace and Piano

Figure 15. Some tenement living rooms had a bed in a closet

Figure 16. Miss Toward’s Kitchen

Figure 17. Unopened box of sanitary towels complete with two safety pins, especially useful when traveling

Figure 18. Definitions of words used in descriptions of paintings and objects so that people are aware of the implications of how people are depicted and objects were collected. All of which is being dismantled in the U.S.A.

Figure 19. This sign, as the one above, are at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum. They are the antithesis of what is happening in America now, after so many years of trying to confront and right the wrongs of racism and sexism

Let’s go now from the infinitely repeatable to the unique and idiosyncratic, from a tenement apartment to a private residence. In the Hunterian Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow, the interiors of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife, the designer, Margaret Macdonald’s home, have been reassembled. Have you heard of Charles Rennie Mackintosh? He enjoyed a flash of fame, but by the time he was 50, his work was so unappreciated that he abandoned architecture and became a watercolorist.

Mackintosh was born in Glasgow in 1868. After his apprenticeship, he worked as a draftsman. With a fellow draftsman, Herbert McNair, he attended evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art. Where the two friends met two sisters - Margaret and Frances Macdonald. The four young artists became entwined both professionally and personally. McNair married Frances and Mackintosh married Margaret. Together, influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, Symbolism and the art of Japan, they created paintings, drawings, metalwork, glass, textiles and furniture.

The Mackintosh House at the Hunterian Art Gallery is the reassembled interior spaces of a mid-19th century home which the Mackintoshes owned and which they modified from 1906 to 1914. The original house, which was demolished in the early 1960s, was only about 100 meters from where the Hunterian is now, so the museum’s reconstructed rooms have the same views and the same natural light.

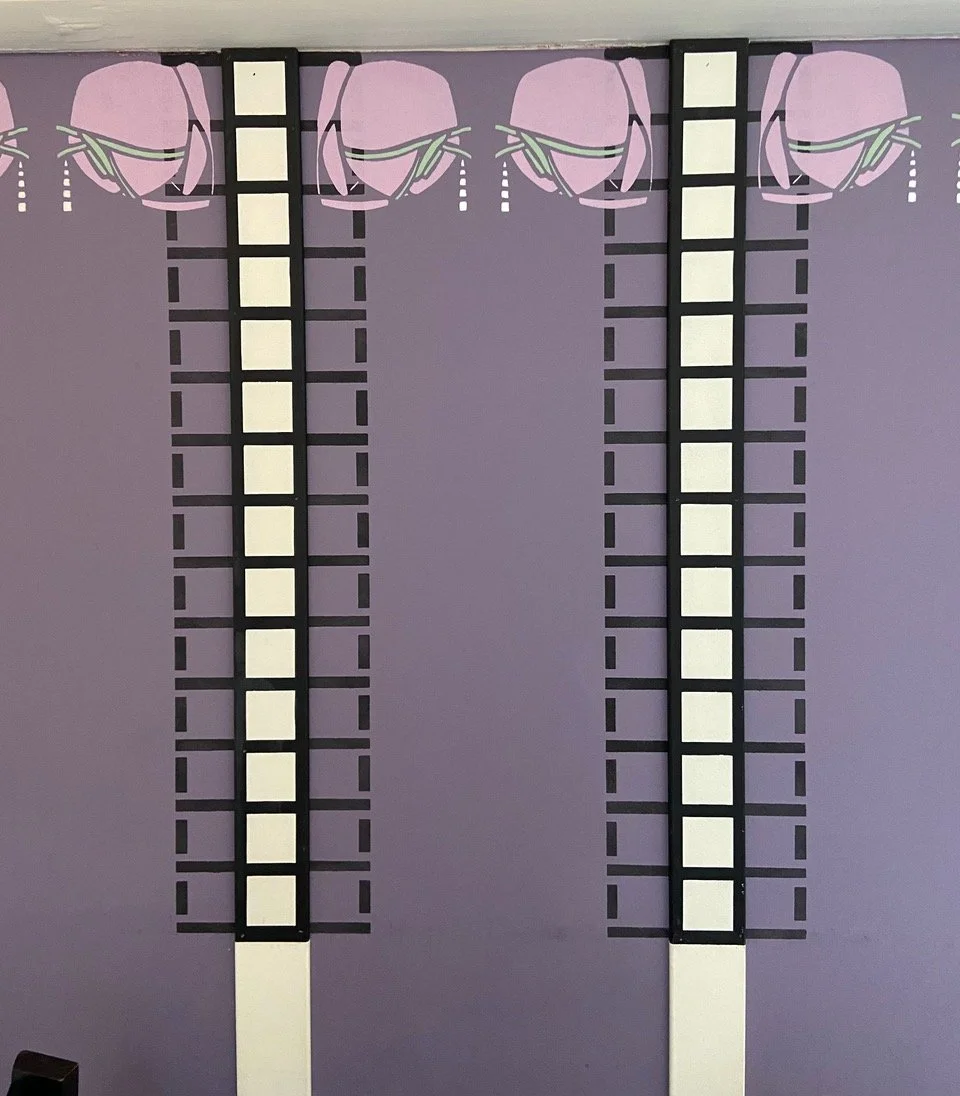

The ground floor Dining Room’s decorative scheme is somber - white ceiling, frieze and stenciled decoration. In this room are Mackintosh’s first and most recognizable design - his ‘high-back’ chairs. The Studio-Drawing Room was initially two rooms that Macintosh made into one L-shaped space which was flooded with light from a horizontal window he cut out on the south wall. The furniture is a mix of dark stained pieces from the late 1890s and white-painted pieces, from the early 1900s. Mackintosh and his wife collaborated on these projects. The white desk that he designed is decorated with silvered metal panels of her design. None of the Mackintoshes’ books were ever located, so the curators have filled the bookshelves with books that either reflect the Macintoshes interests or have decorative bindings that share a sensibility with Macintosh designs. The Bedroom on the upper floor, is, like the Studio-Drawing Room below, two rooms opened up to become one L-shaped space. The furniture, with its sculptural detailing inspired by plant and bird forms, was designed in 1900. The Macintosh House, the only paying part of the museum, has really knowledgable guides in each of the rooms, who are happy to talk Macintosh for as long (and sometimes longer) as you wish. (Figs 20-30)

Figure 20. Charles Rennie Mackintosh (right) and his wife, Margaret Macdonald (left)

Figure 21. Dining Room table and chairs, Mackintosh’s signature high back chair

Figure 22. Studio - Drawing Room with works by both Mackintosh and his wife

Figure 23, Studio-Drawing Room

Figure 24, Mackintosh designed cabinet with designs by Margaret

Figure 25. Desk and Chair designed by Mackintosh

Figure 26. Desk and Chair with fireplace and bookshelves

Figure 27. Chair seen from the back in previous image

Figure 28. Bedroom

Figure 29. Bedroom Mirror

Figure 30. Another project by Mackintosh in Hunterian Art Gallery

Wandering through the rest of the Hunterian, we saw a few more pieces by Macintosh, but our appetites were not sated. There was only one thing for it - tea at the Willow Tea Rooms which Macintosh designed in 1903. It is the only building that Mackintosh designed and furnished in its entirety, and the only surviving of his four tea rooms. The Tea wasn’t the best (Fortnum and Mason and the Palace Hotel have spoiled me) but it was wonderful to be in this space. As the publicity says, “Mackintosh at the Willow, faithful to the Arts & Crafts movement's concept of Total Art , is a must-visit place to immerse yourself in Mackintosh's aesthetic.” (Figs 31-35)

Figure 31. Willow Tea Rooms

Figure 32. Walll decoration, Willow Tea Rooms

Figure 33. Balcony which was not in original plan but which Mackintosh added at client’s request

Figure 34. A bell at every table enabled guests to call servers. The bells are still there, but don’t ring

Figure 35. Willow Tea Rooms exterior and me with a doggy box

We must end our discussion of Macintosh on a bittersweet note, The bitter part is this: After failing to get commissions over and over again, Macintosh became disillusioned with architecture and turned to watercolor. He and his wife left Glasgow and moved to a small village in Suffolk where, according to Wikipedia, “His Scots accent, strange form of dress (he wore a long Inverness cape), and his letters arriving at the post office with German postmarks, led locals to believe he was a German spy, and he was put under house arrest.” That was in 1915. By the early 1920s, the Macintoshes had moved to Port Vendres, a small fishing village on the Mediterranean, in the south of France, near the Spanish border. The weather was good and the rent was cheap. There is a local Charles Rennie Mackintosh Trail in Port Vendres that, with panel reproductions of his watercolors, at the locations he painted them. Alas, their idyll was short lived. He fell ill, they went to London where he died at age 60 in 1927.

Here’s the sweet part, peaking first in the 1980s and then again and again since then, appreciation for Mackintosh’s work as an architect, artist and designer has grown. There was enough interest that The Willow Tea Rooms, where Ginevra and I had tea, reopened after extensive restoration in 2018. That same year Mackintosh's design for the "Oak Room" tearoom was reconstructed as a display at the V&A Dundee, a design museum in Dundee, Scotland, the first V & A museum outside of London. There have also been two exhibitions on Macintosh in the U.S. - at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1996 and at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore in 2020.

Quickly, this is what else we did. We wandered through the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery (named after the man whose collection forms the core of the collection, William Hunter) and admired paintings by James McNeill Whistler and watercolors by Mackintosh. We also visited the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum which, according to them, houses one of Europe’s great civic art collections, including Scottish, European, African, Asian and Oceanic fine and decorative arts. The collections are organized into two halves: Life and Expression. The Life galleries represent natural history, human history and prehistory. The Expression galleries are the fine art collections. We were mostly in the Expression galleries. Among the artists whose works are here, Rembrandt, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Mary Cassatt. Taking pride of place is Salvador Dali’s Christ of St. John of the Cross, (Fig 36) to which the museum cleverly bought the commercial rights. There are paintings by the groups called the Glasgow Boys and the Scottish colorists, who I will tell you about another time. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 36. Christ of St. John of the Cross, Salvador Dali

Thanks to everyone who sent a Comment on Ginevra and my two very different posts on our West Highland Way experience. They are much, much appreciated.

New comments on Beverly’s I did it My Way:

I love reading about your adventures! I used to hike a lot in Europe with hfholidays.co.uk. They have a variety of hiking weeks and leaders of you ever want to try an organized trip. Best, Barbara

That is a wonderful account of an epic trop. You should send it to the Scottish tourist board and suggest they offer it to future walkers. It is getting to be time to suggest contacting publishers, because your blend of art, locations, walks, food and family is very beguiling. Martin, Perigord.

Gorgeous photos! I loved seeing it and reading your narration. And since it's not something I'll be doing, I very much appreciate you sharing it with us. Sydney, Portland, OR

New comments on Ginevra’s Finding Heathcliff:

My dear Ginevra, I loved your article on your Scottish adventure… Of course the style is different from your mom's... Different but very well written and exciting... it was so refreshing, so funny sometimes... I even caught myself laughing, I'll let you guess when...Thank you for this good time spent reading you…, Gérard, Paris

Beautifully written and expressed Ginevra ! I felt I was with you and Beverly every step of the way ! Bravo to you both ! Franny, San Francisco

Loved your take on the trip. Lots of photos. Please pick an easier walk next time for your Mom’s sake. Maybe part of the Appalachia Trail, Deedee, Baltimore

What a great collection of photos and the excellent writing that accompanies them made me feel what you were feeling. I loved that you loved your walk. Noreene, Washington, D.C. & Mexico

Ginevra, thank you for writing a detail of the Highlands Walk. What a spirited adventure you had with your Mom. I applaud you and you have memories forever. Barb, Paris & Atlanta