“I have this urge, this compulsion, to share my enjoyment…” Ma Normandie.

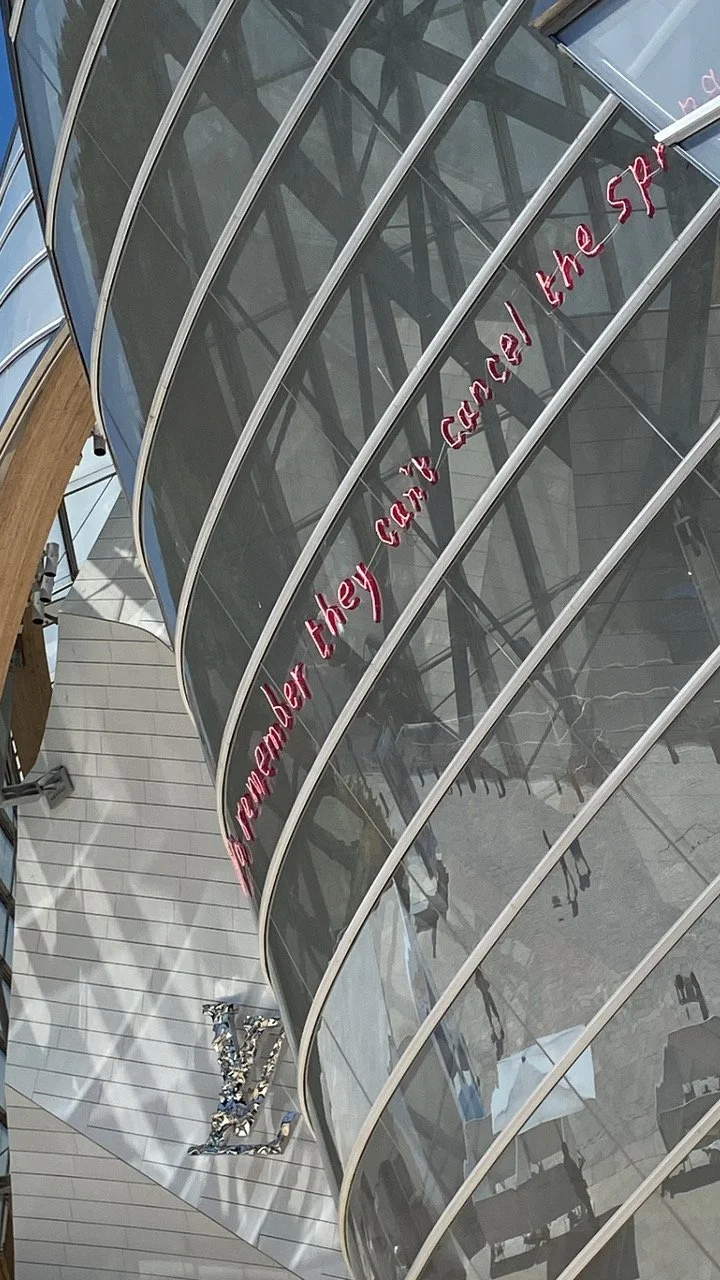

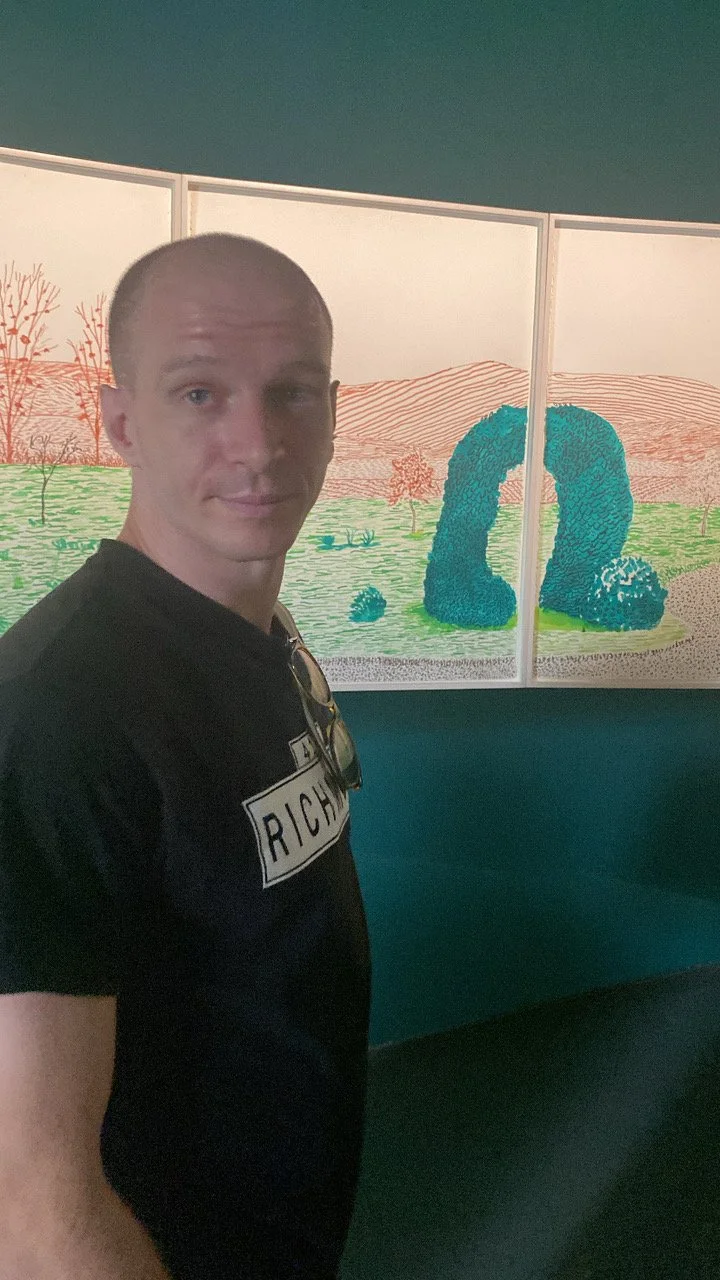

David Hockney 25, Fondation Louis Vuitton

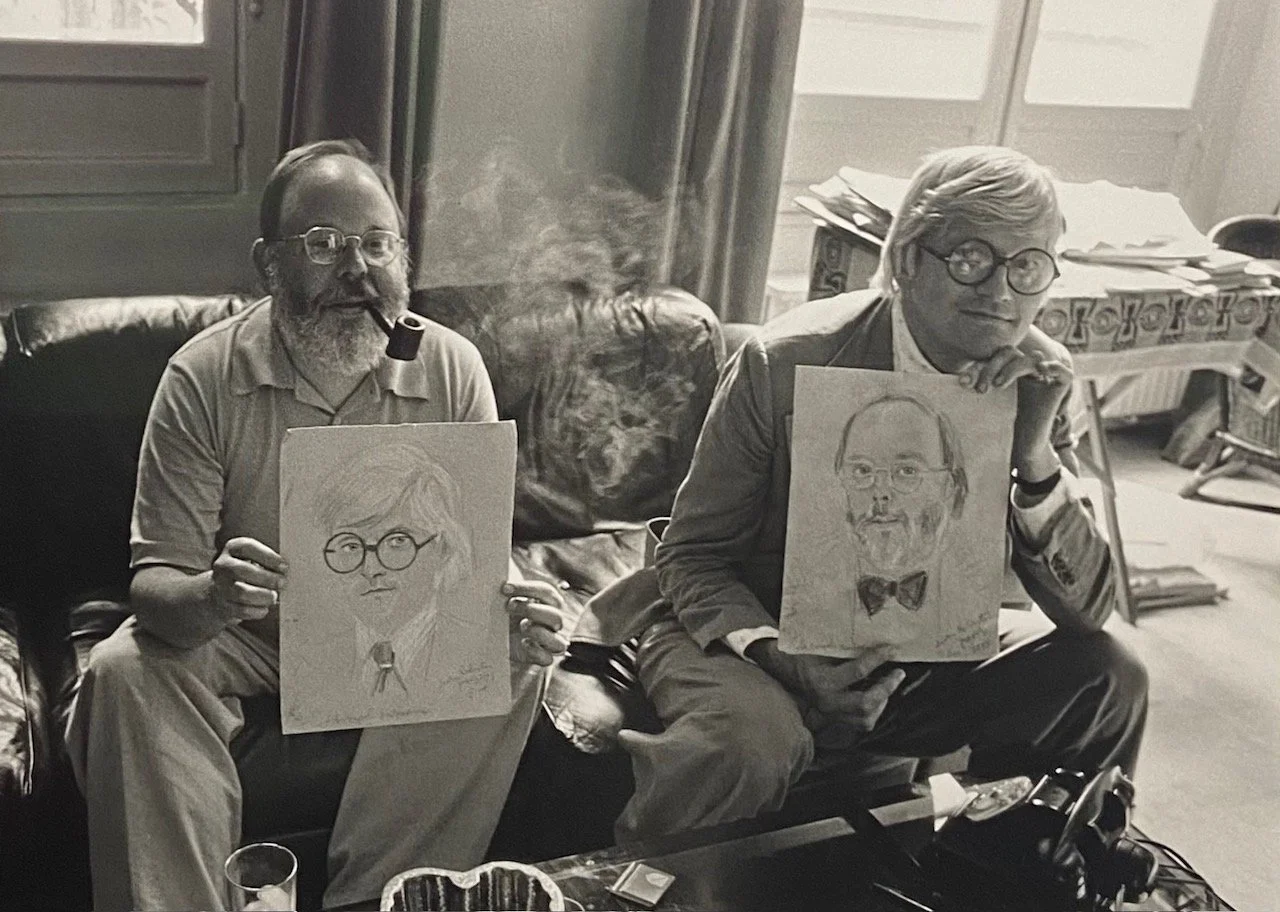

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, I saw an exhibition on the photographer Robert Doisneau at the Musée Maillol. It was fabulous. The photos were divided by categories. One category was artists. One photo was of David Hockney sitting next to Met curator, Henry Geldzahler. (Fig 1) Henry Geldzahler, a very close friend of Hockney's, was also at the Foundation Louis Vuitton, in a portrait by Hockney.(Fig 2) I returned to the FLV, because as the song goes, ‘What the world needs now is love sweet love/It’s the only thing, that there's just too little of/…No, not just for some, but for everyone.” (Fig 3)

Figure 1. Henry Geldzahler and David Hockney, Robert Doisneau

Figure 2. Henry Geldzahler and Raymond Foye, David Hockney, 1979

Figure 3. David Hockney at his home in Normandy

Last week I told you how Hockney found himself in Bayeux in 2018. He was in London for the dedication of the stained glass window in Westminster Abbey that he had designed to honor Queen Elizabeth II’s very long reign. He decided he needed a break. Los Angeles did not beckon and neither did his native Yorkshire. And he didn’t want to stay in London. So he and his partner got into a car and drove to Normandy. Drove because nobody tells you not to smoke in your own car.

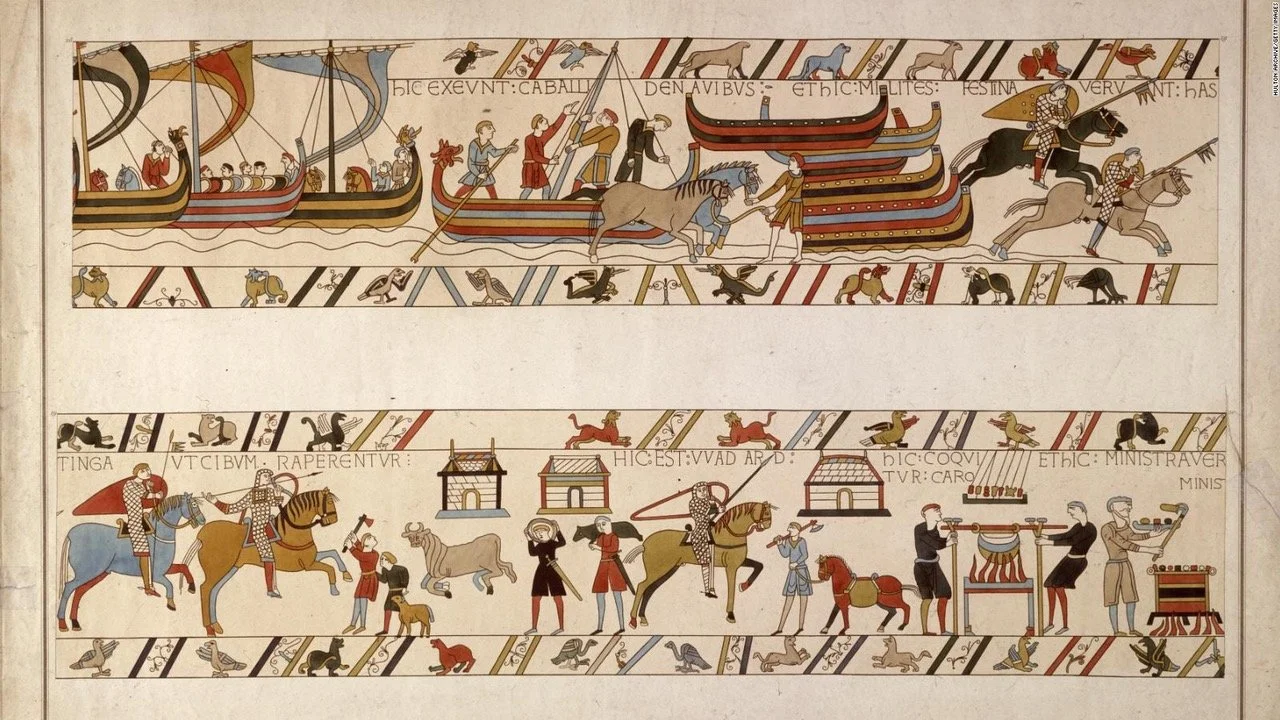

He went first to Honfleur to wander in the footsteps of the Impressionists and then to Bayeux to see the tapestry (embroidery), (Figs 4, 5) which he hadn’t seen since the 1960s. The Bayeux Museum is closing in September for two years. if you can’t get to Bayeux this summer, aim for London next year. The tapestry, which hasn’t been in England for nearly 1000 years, will be at the British Museum from Sept. 2026 - Sept 2027. Museum loans are often reciprocal. The Sutton Hoo Treasure is coming to Normandy. (Their discovery was the subject of the 2016 novel and 2021 film, The Dig )

Figure 4. Some of the many scenes on the Bayeux Tapestry. Central band and upper & lower bands

Figure 5. To give you an idea of how long the Bayeux Tapestry is, Bayeux Museum

If you took an introductory art history course in college, you surely saw at least one image from the Bayeux Tapestry. And that image was most likely Halley’s Comet, which appeared in April, 1066. (Figures 6, 7) Duke William of Normandy interpreted the appearance of the Comet as a good omen. He saw it as God’s assurance that he was good to go. So he went. The Bayeux Tapestry is a a rare example of secular Romanesque art (1000-1200) and an even rarer example of cloth. Tapestries and embroideries adorned churches and wealthy homes in medieval Western Europe. But fabric is fragile and the Bayeux tapestry is one of the very few examples to survive. What makes it even more exceptional is its size, 20 inches high and 224 feet long. Divided into three horizontal strips, the large central panel consists of seventy-five scenes depicting the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England and culminates with the Battle of Hastings in 1066. (Figure 8) Besides being art, the tapestry is also a chronicle of events, political propaganda and information about 11th century weaponry and warfare; everyday objects and activities.

Figure 6. Halley’s Comet (people to left pointing at comet in sky to right) detail, Bayeux Tapestry

Figure 7. Halley’s Comet, detail, Bayeux Tapestry

Figure 8. Battle of Hastings, 1066, central panel, fabulous animals above, fallen soldiers below, Bayeux Tapestry

The images on the upper and lower panels are playful, violent, weird (although not all at once). Fabulous animals from Aesop's Fables, men without pants and in a central panel, at least one woman getting punched. (Figs 9, 10).

Figure 9. Aelfgyva, the woman being punched, detail Bayeux Tapestry

Figure 10. In the band below Aelfgyva, one of many genitalia exposing men in the Bayeux Tapestry

As Hockney walked along the 230 foot length of the Tapestry, he had an epiphany. The tapestry was closer to Chinese scroll painting than to Western image-making because it is ‘read’ over time and in sections—just like a scroll. He felt a new project coming on. He was going to paint the seasons, in Normandy. And for that, he would have to stay for a while. Once again, his requisite pack of cigarettes a day determined the course of events. Better to buy a house than rent one. Rentals come with restrictions, like where and if you can smoke. If it’s your house, it’s your rules.

According to Barbara Isenberg (LA Times, 12/2020) Hockney told her during a Zoom call that he and his partner bought the first place they saw. “We fell in love with it,” he said. “It is a seven dwarfs house in the middle of a 4-acre field. There was a shack that had a cider press in it that could be made into a studio, which we did. When we finished that, I thought I’d start the arrival of spring, but I drew all around the house first, and spring was really over before I got it down.” The house is just outside Beuvron-en-Auge a village of 200 people. Hockney’s house is a typical 17th-century half-timbered cottage, surrounded by poplars and fruit trees; a small pond and a little river; and some out buildings. (Fig 11) That was 2018.

Figure 11. Hockney in his garden in Normandy

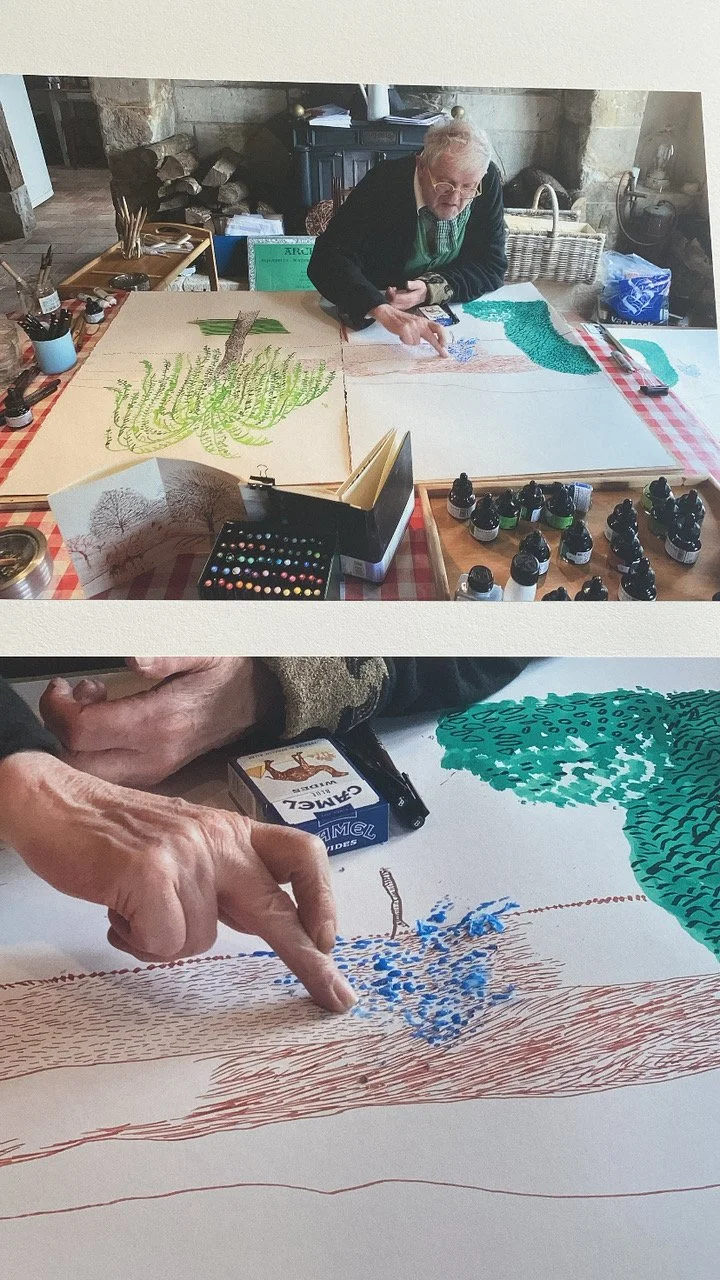

Hockney returned in March 2019. The new studio wasn’t ready but Hockney was. He began filling an 8 inch x 11-foot Japanese concertina sketchbook with a panoramic ink drawing of his new surroundings. Opening like an accordion, Hockney’s drawing makes a 360-degree circle around the house ending where it began.

As Hockney noted, he could paint structures that the Impressionists avoided because to them, the traditional houses were old fashioned. They wanted to paint new things in their new style of painting. But 150 years after the first Impressionist exhibitions, Hockney didn’t feel the same constraints. The houses are there, in much the same way as the landscape is there. He lives in one and is surrounded by the other.

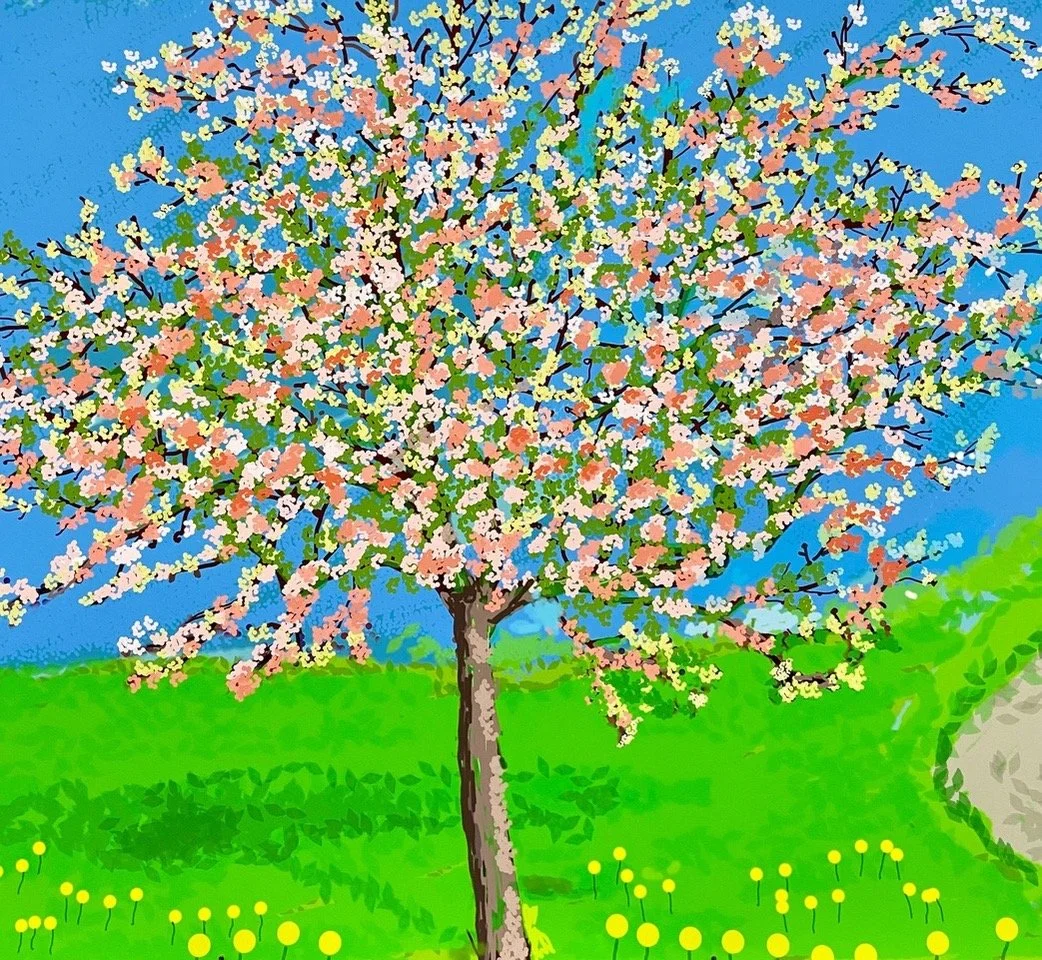

Here’s how Hockney explained it. “I have been working this year 2020, to depict the arrival of spring in Normandy. This takes about three months, and I think it’s the most exciting thing nature has to offer in this part of the world. So when the lockdown came, I didn’t mind. I could concentrate on one thing. I did at least one drawing a day (using an iPad) with the constant changes going on. I kept drawing the winter trees, and then the small buds that became the blossom and then the full blossom. Eventually the blossom fell off, leaving a small fruit and leaves.” (Figures 12-16)

Figure 12. Hockney drawing with his Japanese concertina sketchbook as guide

Figure 13. Hockney working and detail

Figure 14. Hockney working

Figure 15. Nicolas in front of hedge that Hockney is working on above

Figure 16. Hockney at Lelong Gallery, the first place in Paris that the cycle was displayed, October 2020

The idea of painting the seasons as they unfolded was of course not a new one for Hockney. A decade earlier he had done the same in his rediscovered native Yorkshire. He documented its changing seasons with paintings on his iPad and digital videos of the same scene in winter, spring, summer and fall. (Figure 17)

Figure 17. From The Bigger Exhibition, Yorkshire scene, 2014

That exhibition was modestly called ‘The Bigger Exhibition.’ I saw it in 2014 at the deYoung Museum in San Francisco. I was mesmerized by his embrace of the iPad and the video camera. I was not alone, the critic Roberta Smith wrote that the exhibition showed Hockney as “a tradition-fluent progressive working nonstop at the height of his powers, deftly juggling digital and analog modes of representation.”

So, if he had already ‘done’ landscape and seasons in his native Yorkshire, how is his Normandy project different? With Yorkshire as precedent, his Normandy focus is more prosaic. Not a forest, just a house, some outbuildings and the land around them. Hockney painted what he saw from the window of his farmhouse or from his studio or from his garden. With his dog by his side, he drew and sketched and painted and smoked. Mostly uninterrupted. (Figure 18)

Figure 18. Hockney and his dog

How are Hockney’s paintings like the Bayeux Tapestry? With both, a story unfolds. One is a sequence of human events that includes the Battle of Hastings and the victory of the Normans over the English. The other is a story of nature, the passage of time from one season to the next. In both, details provide clues to customs and habits, military uniforms and weapons for one, architecture and planting for the other. (Figure 5 above, Figure 19)

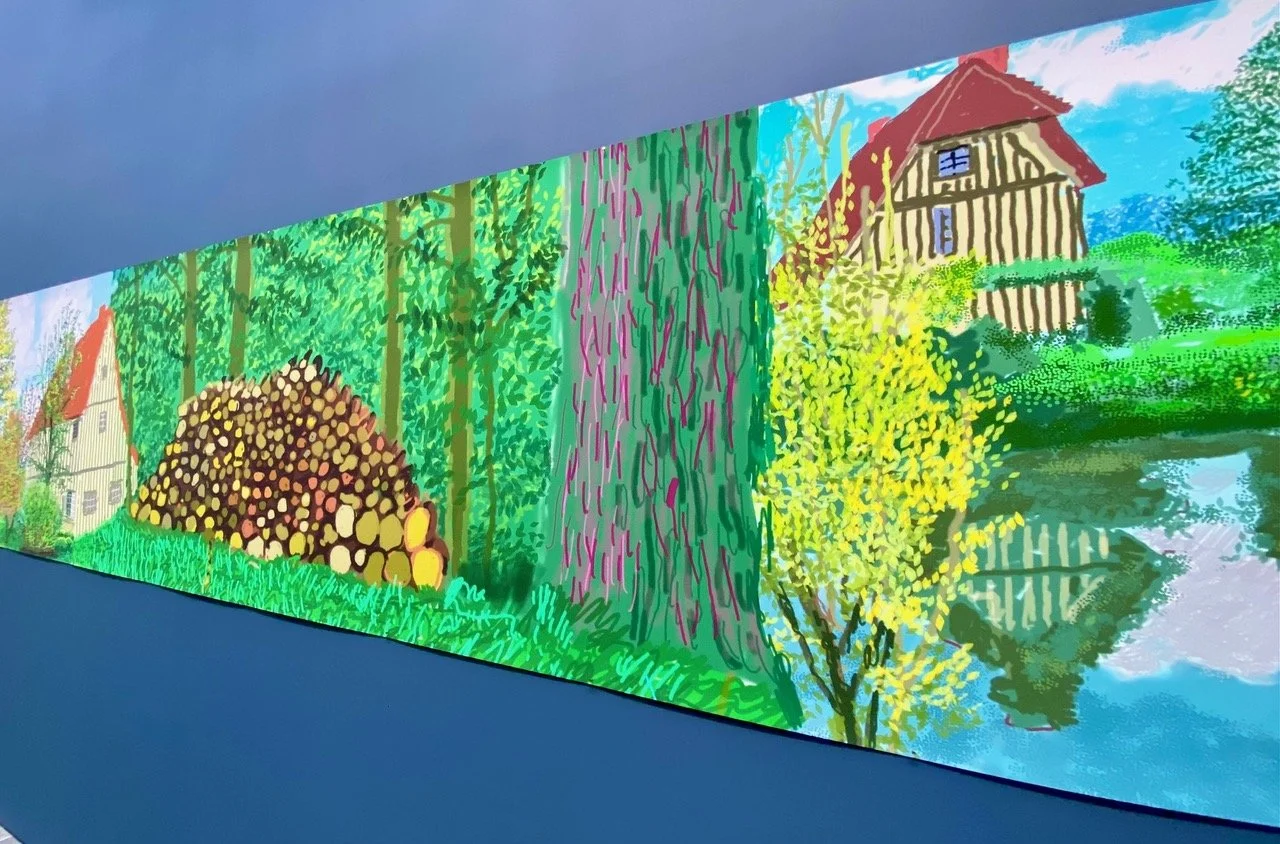

Figure 19. A portion of Ma Normandie, David Hockney

And how is it like a Chinese scroll? As a scroll unfolds, its story is revealed. It is viewed sequentially, in sections.(Fig 20) Hockney’s scenes unfold as we walk along. We see the same landscape but as the seasons change, each repeated motif is different. The trees go from buds to blossoms, leaves fall to the ground and are replaced by bare branches, stark and snow covered. Preparing for the cycle to begin again.

Figure 20. Chinese scroll

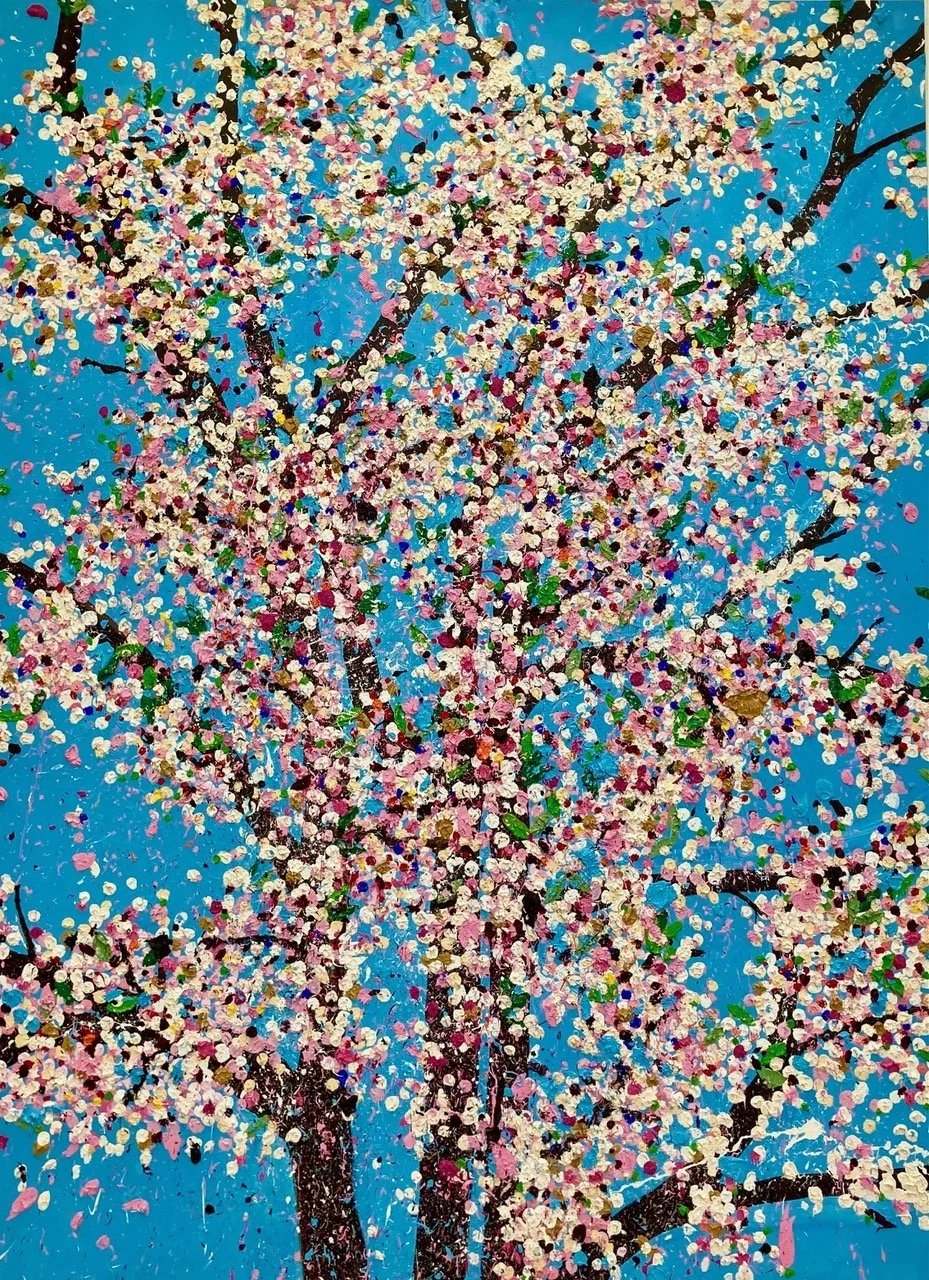

Looking at trees in full bloom, reminded me of Damien Hirst’s Cherry Blossoms exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in 2021. Both artists celebrate what Hirst calls the almost ‘tacky’ abundance of pink and white and red blossoms. Their means are different but the joyfulness of their images isn't. (Figures 21 - 22)

Figure 21. Blossoms, Damien Hirst, 2021

Figure 22. Spring Blossoms, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

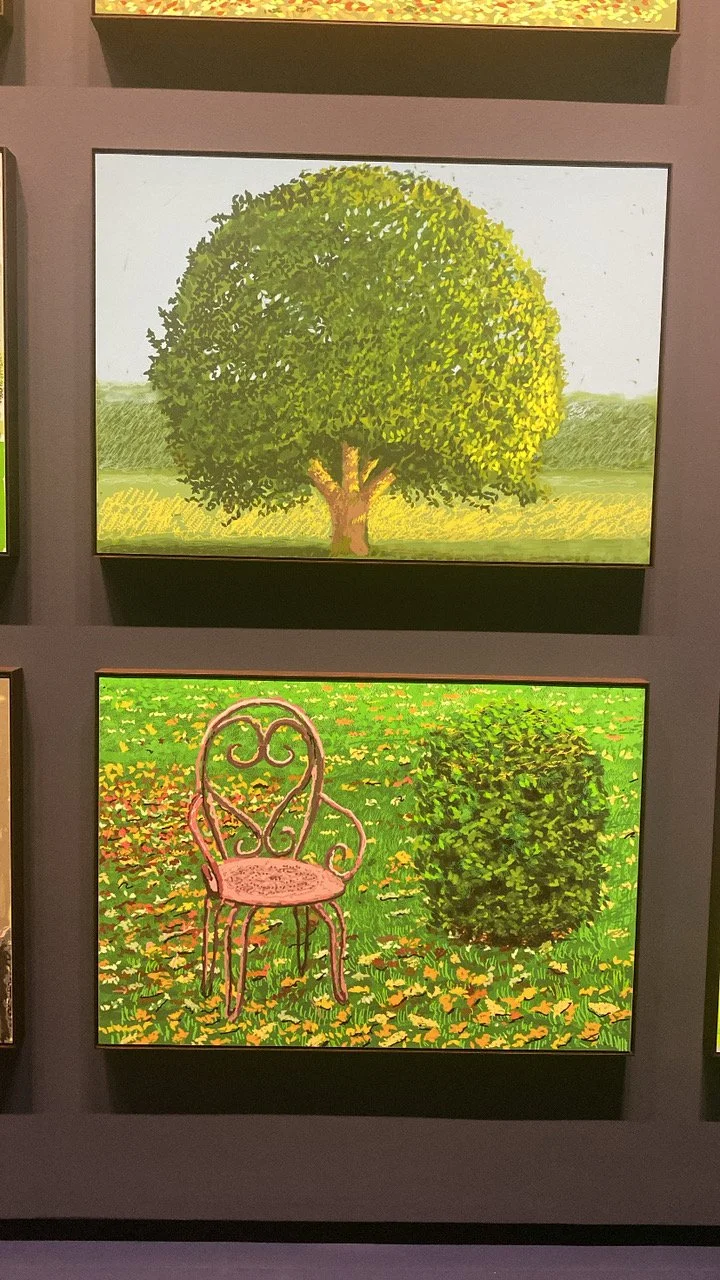

I know the changes Hockney documents. I also have a ‘ring side seat’ to those passages of time in the French countryside. The French café chairs and table in Hockney’s garden, are in my Dordogne garden. (Figures 23, 24) The rolls of hay that Hockney depicts are the ones the farmer makes in my field every year. I don’t pay him to mow my fields. He doesn’t pay me for the hay he rolls to feed his cows and sheep. (Figures 25-27) How many times have I passed my neighbors’ homes and seen stacks of wood placed exactly like the one alongside Hockney’s grange (barn), (Figure 28, 29). Begun in the heat of summer and continually added onto for the winter ahead.

Figure 23. Chair in garden, leaves on ground, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

Figure 24. Photo of my garden chairs, Petit Bout, Dordogne

Figure 25. Rolls of Hay, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

Figure 26. Rolls of Hay, close-up, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

Figure 27. Hay in my field, Petit Rousset, Dordogne

Figure 28. Wood stacked, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

Figure 29. Wood Stacked, detail, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

I first saw Hockney’s paintings of Normandy at the Galerie Lelong at the end of 2020. Museums were bolted shut but through some (brief) loophole (and there weren’t many) galleries were still open. I dressed for the occasion in my Martin Margeila red and white striped (horizontal) sweatshirt and Ralph Lauren red and white striped shirt (vertical). I was so disappointed when I read the signs - no photos. I wanted to have my picture taken in front of the painting of the little village square of Beuvron-en-Auge, all red stripes and red dots against a white background. With little figures walking past shops or seated at tables maybe covered with cloths. (Figures 30-32)

Figure 30. Beuvron-au-Auge, Ma Normandie, David Hockney

Figure 31. Me in Beuvron-en-Auge

Figure 32. David Hockney in front of his painting of Beuvron-en-Auge

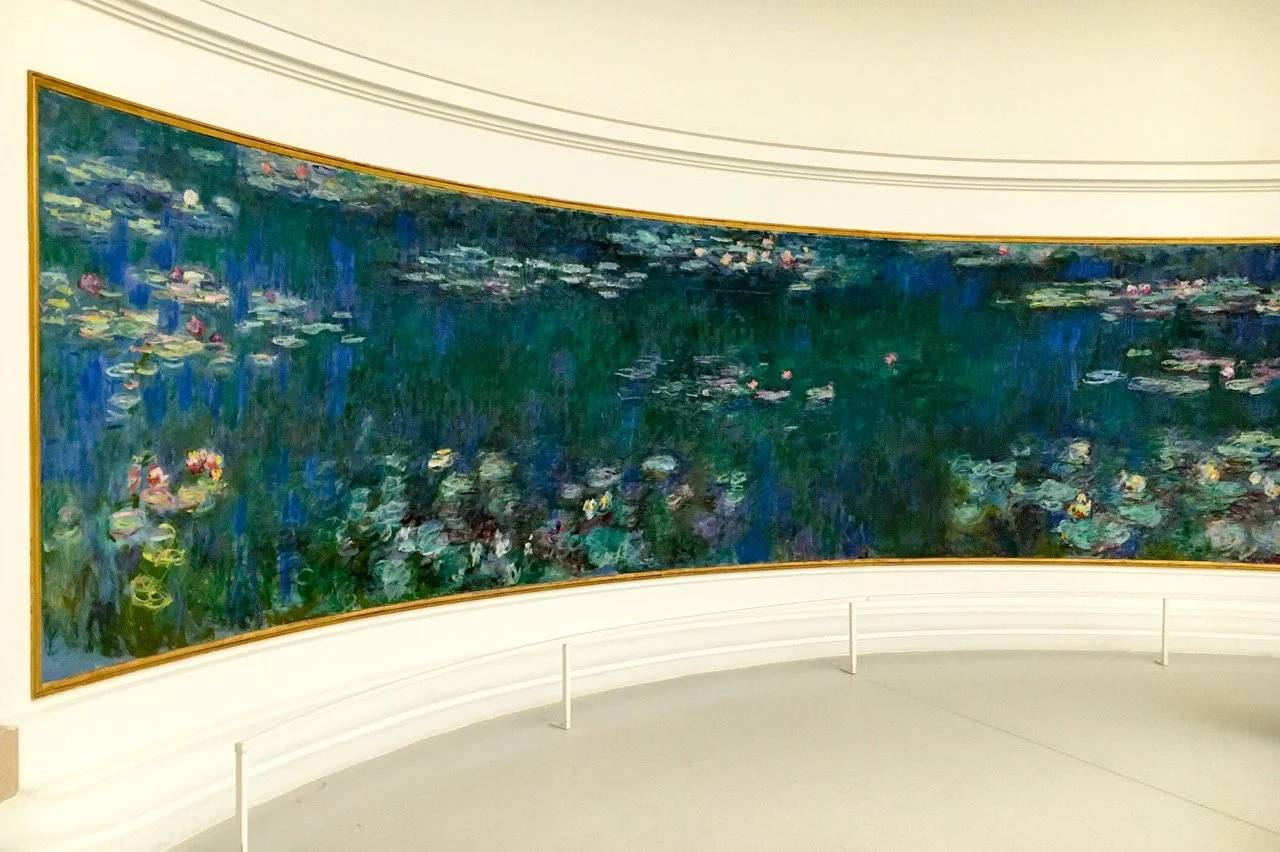

A year later, museums reopened and there was another Hockney exhibition, also entitled Ma Normandie. This one was at the Musée de l’Orangerie (Fig 33). I so hoped it would be different from the exhibition at Galerie Lelong. It was! And this museum, home to eight huge Water Lily paintings by Claude Monet, was the perfect venue.

Figure 33. David Hockney A Year in Normandie, Musée de l’Orangerie

Monet had given his paintings to France at the end of the First World War to provide comfort and solace to a battle weary country. A century later, Hockney showed once again that nature, painting it, looking at it, is perhaps the only reasonable response to a crisis. Hockney’s paintings of the seasons as they unfolded over the course of a year around his Normandy farmhouse provided succor for pandemic weary souls. Hockney’s assistant called these paintings “the Covid collection,” not to make light of the suffering but as a celebration of nature’s tenacity.

Many creatives acknowledged that the ‘Confinement’ was a gift of time. Says Hockney, “When the lockdown came in May 2020, the Olympics were canceled but I realized that they couldn't cancel the spring ... And the spring that year was really wonderful.” Hockney continued, “I had a wonderful time, I worked long hours. I’d go to bed at 9 o’clock sometimes – and sometimes it was still light when I went to bed. But I loved getting up early in the morning, like Monet did….Monet saw 40 springs, 40 summers, 40 autumns and 40 winters in Giverny. They’re fantastic paintings. They’re still very, very fresh… They could have been painted yesterday.…” (Fig 34)

Figure 34. Waterlilies, Claude Monet, Musée de l’Orangerie

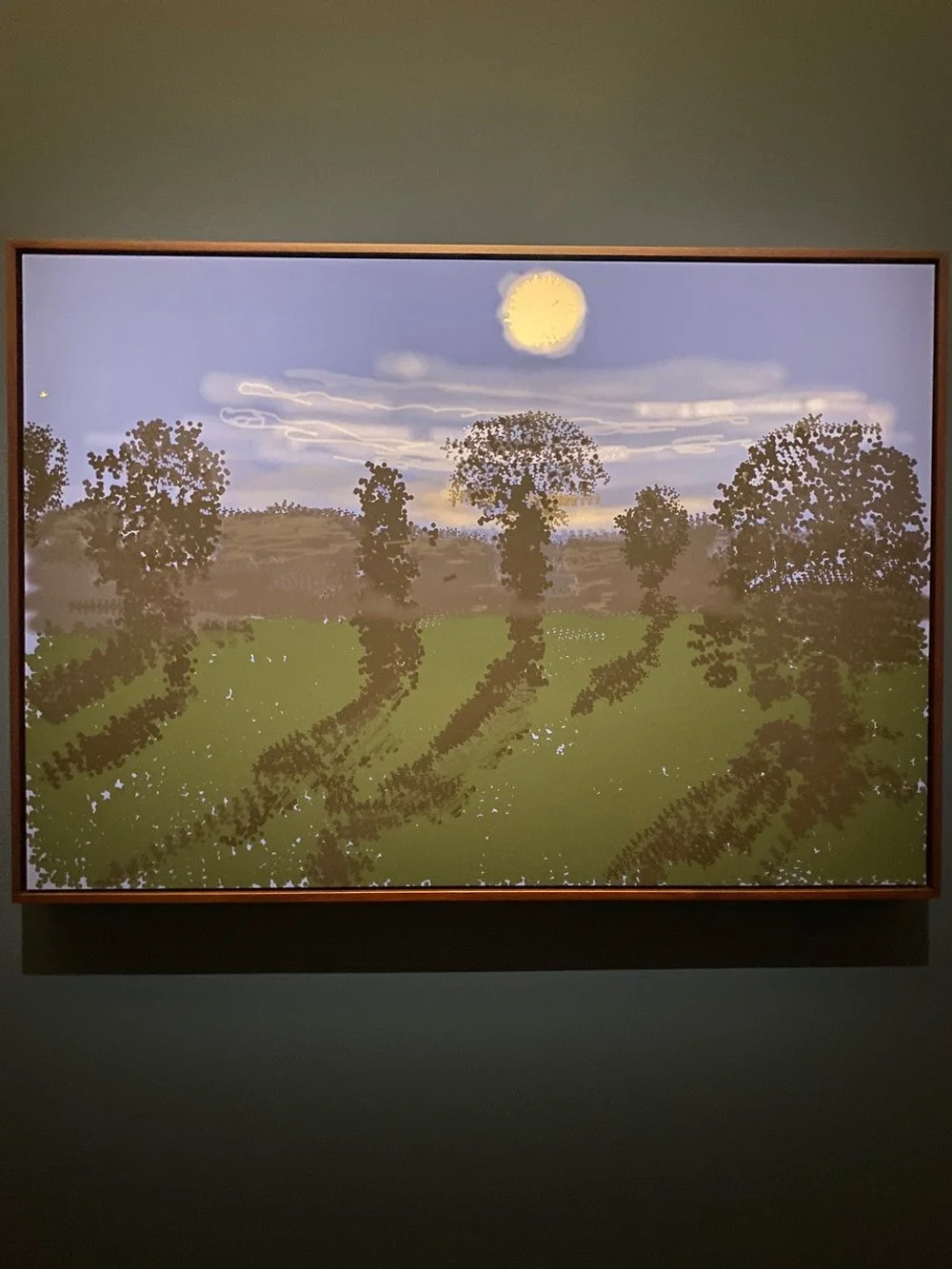

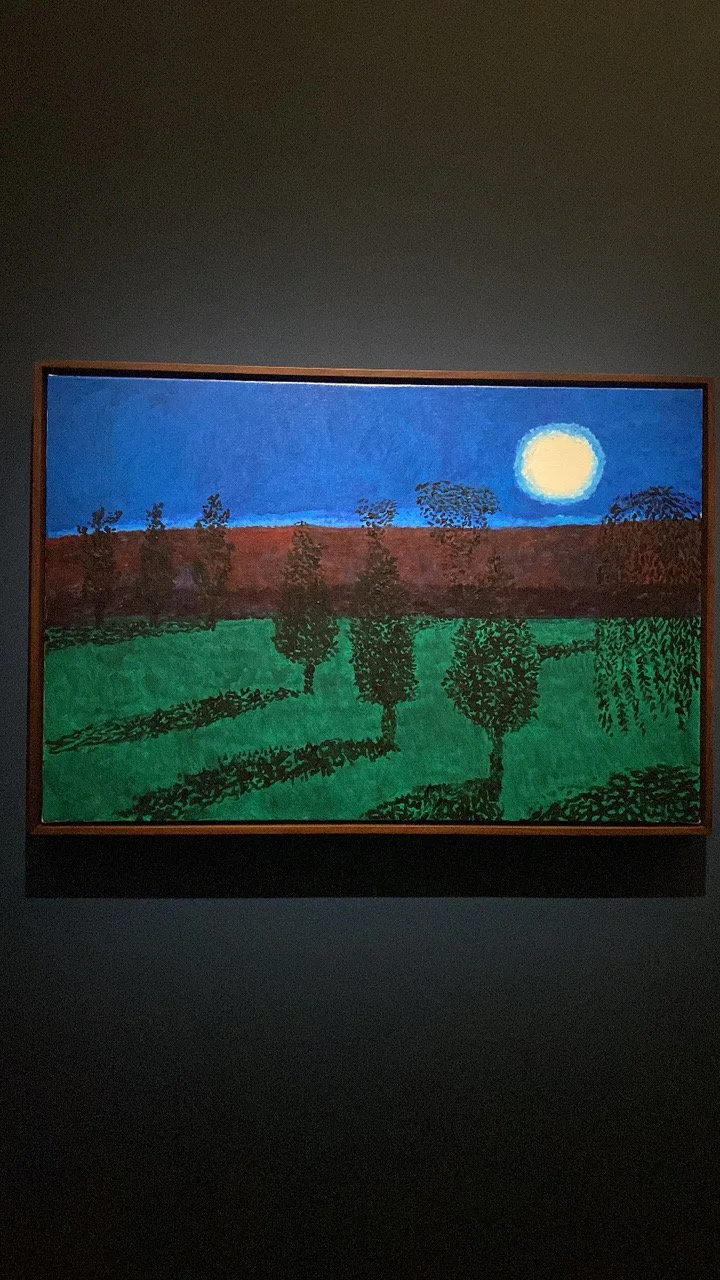

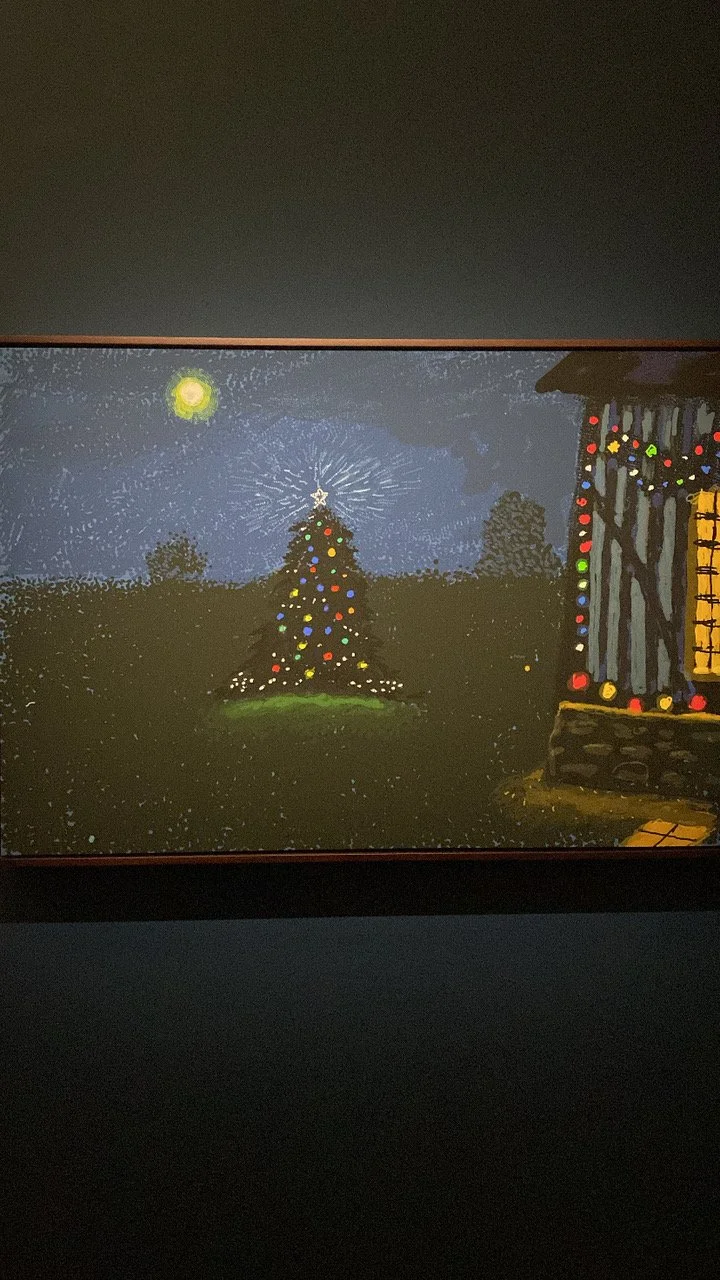

Last year, to celebrate the 150 anniversary of the first impressionist exhibition, museums all over Normandy held exhibitions. At the Musée des Beaux Arts in Rouen an exhibition celebrated Hockney’ Normandism. His painting of Giverny, his homage to Monet was there. (Fig 35) As were his ‘Moon' paintings, nocturnal landscapes created with his iPad, (Figs 36-38) which thanks to the screen's luminosity and back lighting, enabled Hockney to capture the magic of the night sky.

Figure 35. Giverny, David Hockney 2023

Figure 36. Moonlight, 7th May, 2020

Figure 37. Moonlight, August, 2020

Figure 38. Moonlight, 5th December, 2020

Hockney’s love affair with sunshine may be a reaction to where he grew up. Bradford, England became a center of textile manufacture in the 19th century because of the easy availability of coal. When he lived there, Hockney has said, Bradford,“was a very, very black city…The buildings were totally black from coal. ….” Is it possible that Hockney’s fascination with the seasons can be credited to coal and air pollution? Maybe. Probably. As soon as he could, Hockney fled England for sunny Southern California. Where he mostly stayed for forty years. And when he returned to England, it was because he was seduced by …. well, by seasons! As Hockney remembered, “The first spring I’d seen in 20 years was in 2002, I walked every morning through Holland Park. I noticed the spring and I thought: ‘Oh, it’s very exciting, this…”

During the pandemic, Hockney’s Ma Normandie was salve for people’s souls. So much had been taken away. With Hockney’s help, we all remembered that the seasons continued, one after another, one into another, as they always have. Our modern world ground to a halt but the natural world did not. (Figs 39 - 42) Ma Normandie at the FLV includes sketches and drawings and photographs of Hockney working at his home in Normandy. This series remains a reassuring reminder that bullies and autocrats, as they go about ruining people’s lives, cannot cancel spring. Ma Normandie, is as important today as it was 5 years ago. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 39. Outbuildings and trees, Ma Normandie

Figure 40. House and outbuildings and stacked wood, Ma Normandie

Figure 41. Raining, Ma Normandie

Figure 42. Winter, Ma Normandie, David Hockney