Paintings have Patterns, People have Problems

Venus Betrayed: The Private World of Edouard Villard by Julia Frey

I saw an exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg a few years ago called Les Nabis et le Décor. After wandering around the exhibition, giddy and nearly drunk from all the beautiful paintings, I went to the gift shop, as one does. I bought a few carnets, some book marks, a couple post cards. On my way home, I looked to see who had painted the originals. Except for one Bonnard, (the one with the lady in checks that my daughter loves, Figure 1), all the little reminders I had purchased were by Edouard Vuillard. (Figure 2) So I was thrilled to be asked to review Julia Frey’s book on Vuillard and to learn more about the artist. Turns out, paintings have patterns, people have problems.

Figure 1. Women in the Garden , Pierre Bonnard, 1890-91 (My daughter’s favorite is the 3rd)

Figure 2. One carnet was just the wallpaper of this painting

Figure 2. Detail of another carnet

Like me, like many of us, when Frey first saw Vuillard’s paintings, she was drawn to them because they “seemed nearly abstract, composed with conflicting proportions and perspectives and using wildly contrasting patterns…” And again, like most of us, she saw that even though the paintings were decorative, they were filled with figures, mostly women, who, “blend so seamlessly into the background as to be nearly invisible.” I was happy to let it go at that, to find the figures in a sort of ‘Where’s Waldo’ way. Frey went further, she decided to find out if these paintings were about something. To see if the women could be identified and their relationship to the artist explained. Using Vuillard’s diaries with photographs, contemporary accounts and letters, as well as his sketches and finished works, Dr. Frey dug deep and looked wide to contextualize these tantalizing images for us.

Have you heard of Les Nabis? The group of young artists, not long out of art school, who got together and took the name Nabi, from the Hebrew (and Arabic) word for “prophet”. The conceit being that just as Old Testament prophets had revitalized Israel, these artists would revitalize painting, as‘Prophets of Modern Art’.

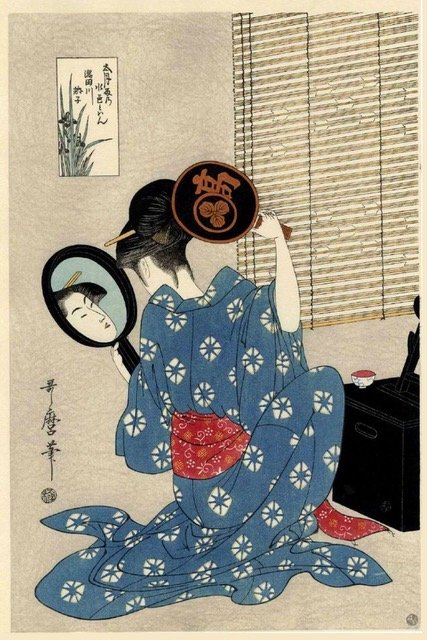

The artists who formed the Nabis included Paul Serusier and Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard and Ker-Xavier Roussel - the last of whom you may not have heard of but who was important to Vuillard and so to us. (Figure 3). They were influenced by Paul Gauguin’s use of bold colors and flattened space (Figure 4) and the strong shapes and bold designs (and flattened space) of Japanese woodblock prints. (Figure 5)

Figure 3. Photo of Ker-Xavier Roussel, left, Edouard Vuillard next, Romain Coolus and Felix Vallotton, 1899

Figure 4. After the Sermon, Paul Gauguin, 1888

Figure 5. Beauties in an Iris Garden, Japanese 19th century woodblock print

Paul Sérusier visited Gauguin in Pont-Aven in 1888. They took a walk in the Bois d'Amour, a picturesque landscape of forest and rocks along the river Aven, Serusier made a small painting of the scene. He used pure, unmixed colors to communicate his emotions rather than mixed and blended colors to transcribe what he saw. Sérusier evoked rather than described the scene before him. This small painting became the ‘Talisman’ (also its name, Figure 6) of Les Nabis, Two years later, Maurice Denis wrote an essay in which he stated “…that a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order." Colors and shapes assembled in an order determined by an artist’s feelings for, response to, the scene before him.

Figure 6. The Talisman, Paul Sérusier, 1888

Like the Impressionists, the Nabis appreciated Japanese woodblock prints for their simplicity of design, their minimization of extraneous details and their elimination of complicated backgrounds. Their flatness also appealed, a flatness they also knew from medieval European paintings and tapestries.

The Nabis’ direct contact with Japanese prints came through their acquaintance with the Paris based German-French art dealer, Siegfried Bing. He began importing Japanese woodblock prints in the 1870s. He organized exhibitions and published a monthly art journal, Le Japon Artistique (1888-1891). Bing supported Art Nouveau artists and the Nabis. The former group, whose artists included Aubrey Beardsley, Gustav Klimt and Alphonse Mucha was active at the same time as the Nabis. Both groups sought to break down the barriers between art and life, between art and decoration. For the theater, they created stage sets and designed costumes. As graphic artists, they designed advertising posters and book illustrations. For domestic settings, they created screens, murals, panels, wallpaper, tapestries, textiles and furniture.

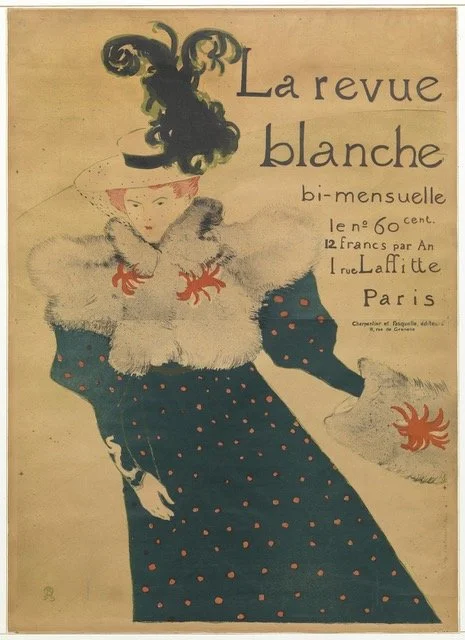

An opportunity to display their art in a domestic setting arrived in December of 1895 when Bing transformed his Paris townhouse into the Maison de l'Art Nouveau. Vuillard was commissioned to decorate a small salon. Which he did with five panels, called The Album. They were either painted for the exhibition or commissioned by Thadée and Misia Natanson (sources vary). Thadée Natanson, with his brothers, owned the avant-garde La Revue Blanche for which members of the Nabis created prints and posters. The three Natanson brothers all appreciated Vuillard’s work, and in addition to commissioning him to create lithographs for their journal, they gave him his first one man exhibition at their Paris office. Thadée Natanson was Vuillard’s friend as well as client and art dealer. An added layer to the relationship was Vuillard’s apparently unrequited infatuation with Natanson’s beautiful and talented wife. Misia. (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Misia, Cover of La Revue Blanche, Toulouse-Lautrec

Since these paintings are autobiographical, let’s start with a few facts about the artist’s life. Edouard Vuillard was born in 1868, in a village in eastern France, the son of a retired military officer. In whose footsteps Vuillard’s older brother followed, but Edouard did not. When Vuillard was 8, his family moved to Paris where his mother opened a corset shop. In Paris, Edouard attended, on scholarship, the prestigious Lycée Condorcet. The school curriculum included twice weekly art classes. He was hooked. He decided to go to art school, to become an artist. Which he did, which he became. It is often said that going to prestigious schools is more about who you meet than what you learn. That was certainly the case for Vuillard. The connections he made at Condorcet lasted his lifetime - his classmates became artists, art dealers and art patrons.

When his father died and his older brother left for boarding school, Vuillard was the sole male in a household of women - his mother, his grandmother (mother’s mother) and his sister who had returned home after 10 years at a prestigious boarding school, to help her mother. (Figure 8) During the day, this all female cast was augmented by seamstresses who came to sew and customers who came for fittings.

Figure 8. The Vine Patterned Dress, (grandmother, mother, sister) Édouard Vuillard, 1891

Before we look at the panels which Bing exhibited, let’s take a look at a commission from 1892, which Vuillard received thanks to Thadée Natanson who convinced his cousin Léonie Natanson Desmarais and her husband to have Vuillard create six panels to decorate the enormous salon of their home. The painting entitled Dressmaker’s Shop (also known as the Garment Fitting, Figure 9) is one of these panels. Frey discusses the painting in the chapter called The Corset Factory. While I won’t be able to share all of Frey’s research and reasoning with you, I can give you a taste.

Figure 9. Dressmaker’s Shop (Garment Fitting), Édouard Vuillard, 1892

Figure 10. Decorations for Hôtel de Nointel, Jean-Antoine Watteau

For subjects, Vuillard drew upon memories of places with which he was familiar, like the garden of the house where he grew up and his mother’s Paris shop. Vuillard knew that decorative designs meant to fill spaces where the same people often gather must be neutral. In the 18th century, during the regency of Louis XV, after the nobles fled Versailles for maisons particulier in Paris, Watteau and his fellow artists decorated domestic spaces with paintings of arabesques, singerie (monkeys cavorting) and pastoral scenes of elegant shepherds and shepherdesses. (Figure 10)

Vuillard’s corset shop is every bit as elegant as Watteau’s pastorales. How is that possible? What did he do to transform the shop into an exquisite decorative panel? One with which others could, as Frey writes, ‘live comfortably everyday’? Vuillard borrowed the ‘femmes fleurs,’ (female flowers) from Art Nouveau designs. (Figure 11) He depicted beautiful women in beautifully patterned garments. Who blended into the wallpaper and the draperies and the bolts of cloth they held up to themselves, that surrounded them, from which they are mostly indistinguishable.

Figure 11. Femme Fleur, Lily Alphonse Mucha, 1898

Did fabrics and patterns play an important role in Vuillard’s paintings because they were so important to his mother? To her livelihood? We have seen how James Tissot’s love for fabric could be traced to his father’s business as a textile merchant. And how Christo’s embrace of fabric stems from the same source. So it seems likely.

Here is Frey’s interpretation of The Garment Fitting. While it is Vuillard’s mother’s corset shop, she is not here. Her absence can be explained by the fact that Vuillard did not want to admit that his mother worked with her hands, (rather than her mind as her wealthy clients’ husbands did). On the far left of the panel, a young woman in white and black leaves through an open door, shepherding a child, arm outstretched, dressed in red, with her. To the right of the door, a woman is seated at a table, also dressed in red, head down, working on a bolt of fabric. Her back is toward the departing woman. At least four women stand, frieze-like, along the wallpapered wall, holding fabric up to their bodies to admire the pattern, to see if it suits them. The final ‘femme fleur’ at the far right of the panel also has her back turned, but she, unlike the seated woman in red, is a customer, dressed in patterned finery.

Frey interprets the scene this way. The beautifully attired women are his mother’s clients. These are women who do not work and who treat women who do work, with disdain and disrespect. Frey suggests that Vuillard’s lifelong insecurity and resentment of social class differences stems from watching how these women treated his mother and his sister in their own home. She suggests that “his use of classic geisha postures, emphasizing the napes of the women’s necks indirectly signals his own feelings of invisibility.” (Figure 12) She interprets the young woman (mother), slipping away with her child as a reference to the impossibility of Vuillard ever marrying, ever making enough money to support a family. I know far less about Vuillard than Frey does, but I can suggest another possible reading. The young woman in red, seated at a table, is working. Perhaps she is Vuillard’s sister. She turns her back on the open door because, as much as she would like to flee, she cannot. Even though some of the careless women here for fittings were probably classmates of hers at the elegant boarding school she had attended. The young mother leaving might well symbolize a life that Vuillard’s sister and not just Vuillard, assumes is out of reach. She had no marriage prospects. Before her lies the life of a spinster (definition of spinster is both and older, unmarried woman and a woman who spins - sews).

Figure 12. Japanese Woodblock print, 19th century

And that brings us to The Album, displayed initially in Siegfried Bing’s Maison de l’Art Nouveau in1895 and subsequently by Thadée Natanson and his wife Misia who had purchased the panels. The first panel, entitled The Striped Blouse is in the chapter called ‘I Dream of Misia’. Three other panels are discussed in the chapter on Vuillard’s friend Kerr Roussel. We’ll start with those. Vuillard met Roussel at Condorcet. Roussel was a year older, richer, and much better looking. He encouraged Vuillard to study art, to take chances, to have fun. And Roussel lived in a household that was the opposite of Vuillard’s. Monied and male. Roussel was a ladies’ man, seducing one woman after another. When he got into trouble, Vuillard was there to help him get out of it. Gradually their roles changed, Vuillard became the stronger one, Roussel became the needy one.

And maybe everything would have been all right except that Roussel, out of the blue, well after Vuillard told him that his sister had a crush on him, proposed to Mimi. He was 26, very good looking, with a mistress (a woman of his own class). Mimi was 32, already a spinster. Of course she accepted. The marriage was a disaster from the beginning and yet it bound Roussel to Vuillard and each to the other’s family in a way that nothing else could. These two best friends became brothers-in-law.

Vuillard documented the early years of his sister’s woes in three of the five Album panels. In Panel 2, (Figure 13) Germaine, Roussel’s red-headed mistress stands in the doorway on the left while Mimi, her back turned, her hair in its usual chignon, arranges flowers at the far right. Between them are at least four other women, one close to Germaine, three others in the center of the horizontal panel, heads together in close conversation. Perhaps trying to figure out what to tell the two young women victimized by the same man, caught in a drama not of their own making but prolonged by their own complicity.

Figure 13. The Album, Panel 2 Édouard Vuillard, 1895

In Panel 5, Germaine, again on the left side appears as a true ‘femme fleur’ her head a blossom in a bouquet of flowers. (Figure 14) In this scene, Mimi is again on the right, and this time she does acknowledge Germaine’s presence. Again they are both surrounded by flowers and patterned wallpaper. In Panel 4 (Figure 15) Mimi is gone and the red-headed Germaine is now on the right. Her back is toward us in this scene as she confronts an older, seated woman. Is it her sister or mother or perhaps Vuillard’s own mother asking the woman to step out of Roussel’s life, out of her daughter’s life?

Figure 14. The Album, Panel 5, The Stoneware Pot, Édouard Vuillard, 1895

Figure 15. The Album, Panel 4, The Dressing Table, Édouard Vuillard, 1895

Two years later, Vuillard documented the continuing soap opera but more directly. Called Large Interior with Six Figures, (Figure 16) in this panel Vuillard’s mother makes an appearance, as do Germaine and her own mother, sister and brother-in-law. All trying to sort out the pain that is Kerr Roussel. An earlier version included Roussel standing in a doorway. But Vuillard painted him out - too obvious. In 1897, the marriage was four years old and both wife and mistress were pregnant by Roussel. The marriage endured. So did the pain and humiliation. But I suppose for Vuillard’s mother, herself a child born out of wedlock, any pain, any humiliation could be endured as long as the woman was married before a child was born.

Figure 16. Large Interior with Six Figures, Édouard Vuillard, 1897

Panel One of the Album, called The Striped Blouse (Figure 17) is one of my favorite of all of Vuillard’s paintings. It has nothing to do with Vuillard’s sister’s woes. Instead it is mostly about Misia, the wife of his former schoolmate, and one of his first patrons, Thadée Natanson. In a chapter called ‘I Dream of Misia,’ we learn a bit about her and a lot about Vuillard’s infatuation with her. As Frey notes, the Natansons ‘not only offered him a haven but also introduced him to a new way of living.’ Vuillard wasn’t the only artist welcomed by Misia. She surrounded herself, led on, flirted with, whatever you want to call it, a ‘core of devoted bachelors’ among them Bonnard, Toulouse-Lautrec and Vallotton. Misia might have been preparing to take a lover, which she eventually did, but it wasn’t Vuillard. He was too poor, too shy, too short. Here is how Frey interprets The Striped Blouse. The red-headed beauty who dominates the panel is Misia. Her effervescence has pushed the two other figures into the background. The closer of the two is Vuillard’s mother, with whom he lived until her death, when he was 60. The other, hovering above and behind Misia to the left, is his mother’s apprentice-seamstress, with whom Vuillard had been in love, whom he may have gotten pregnant, whom he certainly abandoned. Three ‘femmes fleurs’ surrounded by, enfolded by, flowers everywhere - in the vase, on the table, behind Vuillard’s mother. Apparently the chintzes, wallpaper, carpets that Vuillard painted actually were the decorations of the Natansons’ home(s), purchased at Le Bon Marché, selected with Vuillard’s advice.

Figure 17. The Album, Panel 1, The Striped Blouse, Édouard Vuillard, 1895

Some viewers disliked Vuillard’s Album panels because they couldn’t tell what was going on. They saw figures, they wanted a narrative. The art critic, Felix Feneon, didn’t agree. “The pleasure of naming the subject plays a role, no doubt, in the pleasure the images provide but it is not the essence, the essence is abstract.” You and I, like Feneon, don’t need a story. Our eyes have been trained over years of abstract painting. And yet it is nice to have one, thank you Dr. Frey.

The first year of the new century, the Nabis held one last exhibition and then went their separate ways. In 1937, just three years before he died, Vuillard summed up the breakup of the Nabis this way, "...The march of progress was so rapid. Society was ready to welcome cubism and surrealism before we had reached what we had imagined as our goal. We found ourselves in a way suspended in the air.”

After the members of the Nabis parted ways, Vuillard left Misia. He didn’t find an eligible woman to marry. Instead he took up with Lucy Hessel, the wife of his next art dealer, Jos Hessel. (Figure 18) That relationship, with its numerous traumas and dramas and indiscretions, endured for 40 years, until the artist’s own death. There were three women who figured prominently in Vuillard’s life and in his paintings - his mother, Misia and Lucy. For Lucy’s friends and Jos’ clients, Vuillard painted portraits that were as much about his clients’ stuff as it was about them. They are surrounded by their accumulated possessions, yet now distinguishable from them. (Figure 19) He has moved on and in a sense moved back to a more traditional style, one more in step with his clients’ taste.

Figure 18. Jos and Lucy Hessel in the Small Salon, rue de Rivoli, Édouard Vuillard, 1903

Figure 19. Marcelle Aron (Mme Tristan Bernard) Édouard Vuillard, 1914

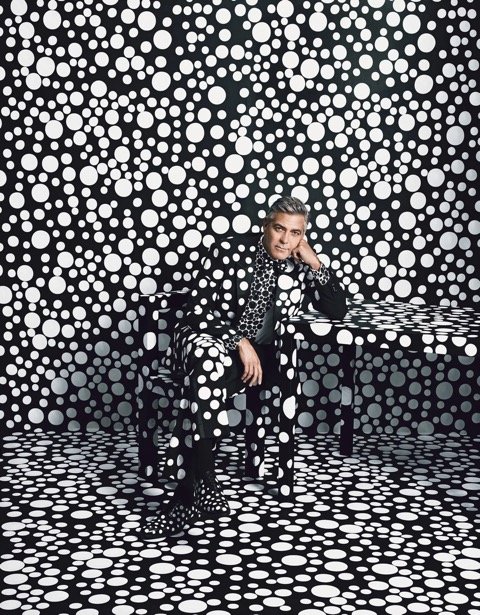

Postscript: Do you think there is such a thing as an homme fleur? Because I think I have found an example on my Instagram feed lately. It is a portrait of George Clooney in a Giorgio Armani suit designed by Yayaoi Kusama using her trademark polka dots. The wallpaper, floor, chair and table which surround Clooney are also in polka dots. He has become an homme pois (French for both pea and polka dot, Figure 20)

Figure 20. Photograph of George Clooney in a Giorgio Armani suit designed by Yayaoi Kusama, 2013

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you