Patterned Perfection

Omar Victor Diop at MAGNIN-A

El Moro, based on painting by Jose Tapiro y Baro, from Diaspora Series, 2014 (Omar Victor Diop/MAGNIN-A)

I saw a wonderful exhibition on Friday. At a gallery down the street from my apartment. I feel so lucky to be able to say that. I mean how many people can really say that except for maybe John and Ellen who live in Chelsea, New York, not London. The abundance of galleries in and around my neighborhood, has compensated in some measure for the absence of museums, everywhere. But, I am not going to get too dependent upon the galleries because, well, the next confinement is imminent. And It has become painfully clear that Macron & Co. are no better at handling this mess than the Trump machine was. And well, because, AstraZeneca.

And then there is the weather, which is so unpredictable that even when rain is predicted, which is almost always, you can walk around with an umbrella as an appendage and never open it, not once. And then when you dash out, just once without your umbrella, to buy eggs for the apple cake (recipe Melissa Clark, NYT) you have already started, of course, you get soaked on the way home. Or even when you do have your umbrella, the 10 minute walk from the gallery, in the torrential rain which began just as you started home, with the wind winning the war against your umbrella, you will get home, completely soaked. So, there you go.

One might agree that March in Pandemic Paris is not the stuff of dreams. And yet, and yet, there are the art galleries, and they’re all here, well, Tuesday through Saturday until 6p.m. because of the curfew ….. and only until the next confinement which might be announced any day now and which will change everything with little warning but with big repercussions.

UPDATE: Since writing the above, we are on lock down again and art galleries (but not hair salons) are closed, at least for a month. And everybody who could leave Paris, has, again.

So, Friday. The gallery, down the street from my flat. MAGNIN-A. The show I saw is scheduled to be up for the next few months, but probably not long enough for you to feel safe enough to come here or for France to let you in anyhow, even if you already have your vaccine because I probably won’t have mine yet. Putting that aside for the moment.

MAGNIN-A, founded by André Magnin in 2009, describes itself as an art gallery with “an aesthetic and political project, engaged in the promotion of African Contemporary artists.” The show I saw, a photography show, was entitled ‘HERITAGE Carte Blanche to Omar Victor Diop’. In which the photographer Omar Victor Diop selected the work of six photographers and juxtaposed their work with his own, creating a dialogue of contrasts and comparisons, which is just what the art historian in me needed.

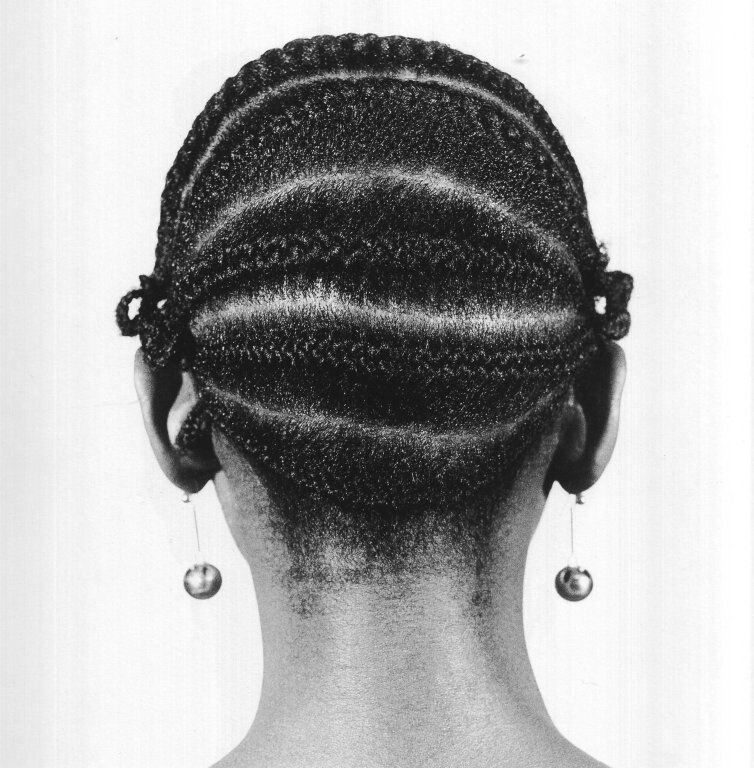

Figure 1. Hairstyle Series, Okhai Ojeikere 1968 - 1975

We’ll consider the fabulous photographs of Omar Victor Diop in a moment. But let’s start with Okhai Ojeikere who is represented by twenty or so photographs of women with very elaborate hairdos, a small sampling of Ojeikere’s Hairstyle series.(Figure 1) As the press release confirms, these images are ‘a unique anthropological, ethnographic and documentary’ record.

And I started thinking, as one does, about hair, about conformity and rebellion. I wanted to know more about these hairstyles, what they meant then and what they mean now, and to whom. And of course, Beyoncé. Here is a little of what I learned.

The history and tradition of African hairstyles is long and complex, like the hairstyles themselves. As early as the 15th century, hair could identify a person’s community, age, marital status, wealth, power, social position, and religion. Members of royalty wore elaborate hairstyles as a symbol of their stature. As a symbol of fertility, if a woman’s hair was thick, long, and neat, it was thought to be a sign that she could bear healthy children. But a woman in mourning did not take care of her hair, so that men would not find her attractive. Finally, hair dressing was not a profession, women did for each other. But only a trusted relative or friend, because if any of your hair got into your enemy’s hand, they could harm you.

Figure 2. Bantu Knots, Okhai Ojeikere, 1968 - 1975

Figure 3. Cornrows. Okhai Ojeikere’ 1968 - 1975

There are Bantu knots (Figure 2) (the word means people) in which the hair is sectioned off, twisted, and wrapped so that it forms spiraled knots. Then there are cornrows so named because they look like cornfields. (Figure 3) These tight braids, laid along the scalp, represent agriculture, order and a civilized way of life. Why did Bo Derek have cornrows, or more specifically Fulani braids in he 1979 film ’10’? (Figure 4) And why did Kim Kardashian call those braids, Bo Derek braids? Cultural appropriation, anyone?

Figure 4. Bo Derek ‘Fulani braids,’ film, ’10’ 1979

Beyoncé’s hairstyle in the 2020 ‘Black is King’ (a riff on the Lion King)(Figure 5) is based on the hairstyle worn by the Mangbetu tribe of the Congo which required an elongated skull, which was achieved by tightly wrapping the head of a child from birth until 3 or 4 years of age. (Figure 6) It was only done to babies born into the ruling classes, just like foot binding was only for upper class Chinese girls who, as women would be incapable of moving, let alone doing anything useful. To the Mangbetu, an elongated head meant majesty, beauty, power and intelligence. The hairstyle is achieved by winding braids around the elongated head. At the top is a basket-looking crown.

Figure 5. Beyoncé, Mangbetu hairstyle, ‘Black is King,’ 2020

Figure 6. Mangbetu hairstyle, 1920-30, C. O. Zagoutski

So hair: When black women straighten their hair, they are accused of buying into a definition of beauty dictated by the dominate culture. When white women wear traditionally black hair styles, they are accused of cultural appropriation. And when Beyoncé does it, she is both praised and criticized for her ‘western’ interpretation of an Africa hairstyle.

Some of the women in Ojeikere’s photos show scarification, the markings made by cutting the skin and manipulating the healing process to create complex and delicate patterns. Africans and Australian Aboriginals used cutting because other forms of permanent markings, like tattoos, for example, are not visible on dark skin. The main point of African scarification is to beautify and to identify. Traditional scarification has waned since the beginning of the 20th century, indeed some African governments have banned it as 'anti-patriotic tribalism’. And yet, since the late 20th century, scarification has found American and European adherents.

Hairstyles and scarification originally signaled tribal affiliation. But when people left their rural homes for urban areas, the identification became increasingly less important, increasingly restrictive. The city enables people to break free of constraints and escape from prejudices. When braided hairstyles and scarification began to appeal to Europeans and Americans in the late 20th century, it was to break free from societal norms. Of course it does that, but it also establishes other identities, too, conforming to non-conformity.

Figure 7. Female sitter, Mama Casset, 1950

Now that we’ve gotten body adornment out of the way, let’s think about pose and clothes. And Mama Casset, a man of the 20th century, born 8 years after it began and died 8 years before it ended (1908-1992). One photo, from 1950, depicts a woman from the waist up, set against a plain background, wearing a traditional headdress and an elaborate top of African design. (Figure 7) Casset’s photographs are significant because they were taken by an African photographer for an African clientele. At a time when Africans were increasingly opting for Western attire, Casset’s sitters are depicted with specific tribal affiliations. Casset’s photos depict neither a ‘struggling African populace’ nor the ‘exotic other’ so typical of Western photographs taken for European audiences.

Before we get to the work of Diop, which you will love, I promise you, let’s look at a portrait of a young woman by Saydou Keita which plays with African and art historical motifs. (Figure 8) A full length portrait of a reclining young woman, wearing traditional dress and headdress, entitled ‘L’Odalisque’ would have been a perfect riff on Manet’s Olympia (Figure 9) if her white maid was standing behind her with a bouquet of flowers.

Figure 8. Odalisque, Saydou Keita, 1956-57.

Figure 9. Olympia, Edouard Manet, 1865

Now what I’ve been waiting to tell you about since we got here - the photographs of the show’s curator, Omar Vincent Diop. Who was born in Dakar in 1980. Who graduated from the very prestigious Ecole Superieure de Commerce de Paris. Who won a photography award in 2011 (the announcement for which he initially thought was a prank email from a friend). Who the next year, at the age of 32, quit his secure and well remunerated job in finance and became a photographer. Which was 10 years ago. Whose work is incredible. Period.

Pose and patterns are the two words that spring to mind when I look at Diop’s glorious photographs. The images are at times witty, at times poignant, but they are never anything less than visually stunning. The richness and complexity of the intensely colored and patterned fabrics worn by his sitters and used as backdrops, just makes me happy, seriously happy, joyfully happy. The riot of patterns and colors remind me of Matisse, what I love best about Matisse, what I respond to most viscerally in his work and in the work of Diop. Beyond Matisse, Diop is inspired by the photographers he selected for this show and the work of fashion photographers like Richard Avedon and Annie Leibovitz.

Figure 10. (left) Photo based on portrait, Diaspora Series, 2014 Omar Victor Diop, Fdn. Louis Vuitton. Figure 11. (right) Portrait of Juan de Pareja, Diego Velazquez, 1650

Figure 12. Left Photograph based on portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley (Right) by Anne-Louis Girodet. 1797. Diaspora Series, 2014, Omar Victor Diop/ MAGNIN-A

If you look at his website, which I urge you to do, you will see that his Fine Art work is divided into series. One is the Diaspora which he began in 2014. Photographing himself and using historical paintings as models, he created portraits of famous Africans from the 15th to the 19th century. For example, Juan de Pareja, a Spanish painter, born near Málaga, Spain. He was a member of the painter Diego Velázquez’s household and eventually became Velazquez’s assistant. Diop’s photograph is based upon Velasquez’s painting of Pareja. (Figure 10, Figure 11) Or how about Jean-Baptiste Belley, (Figure 12) a freed slave from Senegal, who during the French Revolution was a member of the National Convention and the Council of the Five Hundred. This photograph is based upon a painting by Anne-Louis Girodet. And then there is Frederick Douglass, (Figure 13) the American social reformer, abolitionist, orator and writer, who after escaping from slavery in Maryland, became a national leader of the abolitionist movement.

Figure 13. Frederick Douglass, photograph based on a daguerreotype by Samuel J. Miller, 1847-52.Diaspora Series,2014 Omar Victor Diop/MAGNIN-A

Diop explained the series in an interview with Sean O’Hagen of The Guardian, (11/07/2015). “It started with me wanting to look at these historical black figures who did not fulfill the usual expectations of the African diaspora insofar as they were educated, stylish and confident, even if some of them were owned by white people and treated as the exotic other. I wanted to bring these rich historical characters into the current conversation about the African diaspora and contemporary issues around immigration, integration and acceptance.”

As you look at the paintings, I hope you will notice one element that seems completely out of place, for which you have to do a double take, and that is, football, soccer gear. For these, Diop explains, “Soccer is an interesting global phenomenon that for me often reveals where society is in terms of race. When you look at the way that the African soccer royalty is perceived in Europe, there is a very interesting blend of glory, hero-worship and exclusion. Every so often, you get racist chants or banana skins thrown on the pitch and the whole illusion of integration is shattered in the most brutal way. It’s that kind of paradox I am investigating in the work.”

Figure 14. Breakfast for the Children, Black Panthers 1969, from Liberty Series 2016, Omar Victor Diop/MAGNIN-A

Figure 15. Trayvon Martin, 2012, Liberty Series 2016. Omar Victor Diop /MAGNIN-A

There is another series called Liberty which “recalls, interprets and juxtaposes moments of Black protest … placing them in the .. chronology… of a frantic quest for freedom. (The) history of Black protest is rich, whether slave revolts, marches for emancipation and against apartheid, movements for independence, or against police violence….” The photo from this series in the show is called ‘Free Breakfast for the Children,’ (Figure 14) which the Black Panthers started in Oakland, in 1969. Each photo includes a symbolic flower. In this photo it is sunflowers, symbol of faith and loyalty. Another photo, of a fallen Trayvon Martin, wearing his hoody on a bed of Skittles, which he was holding when he was shot dead. (Figure 15)

Figure 16. Animata Faye. The Studio of Vanities Series, 2013. Omar Victor Diop / MAGNIN-A)

Two series are lighter. The website describes The Studio of Vanities series, (Figure 16) “These are the fresh faces of the continent's urban culture….They are creative and ambitious, but most importantly, they dedicate their everyday lives to making their dreams a reality….” To Rozami Azami of Le Monde, Diop said, “I want to portray dynamic urban Africans, bloggers, designers, entrepreneurs.” To celebrate, not apologize for being African, for being a proud African. Diop continued, “It is not bad luck to be African, it is on the contrary a sacred luck, because we are chameleons. We spontaneously speak Wolof, we learn French at the age of 3, English at 12.” It is the next sentence that made me laugh because it is so true, “ If I had been a young American from the Midwest, I would only speak English, I would not have a passport.” Of course he is not talking about you midwesterners from Chicago!

And finally, Alt + Shift + Ego which the website describes as “A sort of laboratory in which staged portraits and fashion photography merge in an experimental way.” The photo of the two young men set against a gorgeous background is too wonderful. (Figure 17)

Figure 17. Alt + Shift + Ego Series, since 2013 Omar Victor Diop / MAGNIN-A

As I was musing about all the amazing patterns and colors in Diop’s photos, I started thinking about African textiles in general and my face mask in particular. Which I got at the Musée de la Toile de Jouy, in Jouy-en-Josas, (5 minutes from Versailles), merch from an exhibition entitled “Fibres africaines,”. When I think of Toile de Jouy, I think, as you do, of repeating pastoral scenes, in pastel colors on an off-white background. (Figure 18) But just like other museums in France, this one stays relevant by expanding its horizons and that is how I came to own a mask on which the repeating pattern is African.

Figure 18. Toile de Jouy

The exhibition, curated by Anne Grosfilley, an anthropologist who specializes in African wax fabric, explores the creativity and diversity of African textiles. (Figure 19) Yes, they were developed to cover the body, but from the beginning, the styles, patterns and colors were used to identify its wearer by place of origin, age group, social status. Even as industrial fabrics flood the market, African fashion designers continue to promote traditional techniques and fabrics.

Figure 19. Fibres Africaines. Musée de la Toile de Jouy, Oct. 2020-Mar 2021.

Figure 20. Dior Cruise 2020.

I heard an interview with the curator of the exhibition in which she talked about having advised Maria Grazia Chiuri, the first female and current creative director of Dior. They had visited African artisans making wax fabric by hand, Grosfilley’s speciality. Chiuri’s designs for Dior Cruise-wear 2020 combines really gorgeous clothes with really gorgeous African fabrics. Some people loved it but the culture police cried ‘Western Appropriation’. (Figure 20)

As I thought about the legitimacy of European designers using African textiles made by African artisans, for Western attire, I remembered wandering into a boutique in Bangkok that sold contemporary fashions embellished with antique kimonos. The new creations and the pieces of old kimono were gorgeous together. And I wondered at the time if it was somehow sacrilegious to cut up an old kimono for a modern dress. And if that was sacrilegious then what about destroying garments for patchwork quilts. But surely quilts prolong the life of a textile by giving it a new one. But here the issue is using traditional African textiles to create modern western clothing. If signs and symbols are unwittingly incorporated into the designs, is that sacrilege? And if no disrespect is intended, is it better to give employment to artisan craftsmen rather than let their craft die with them?

Figure 21. Portrait of Barack Obama, Kehindi Wiley, 2018

Diop is not the only artist who has been using colorful patterns, African patterns, lately. Kehindi Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama. (Figure 21) depicts the former president wearing a suit, of course but the background is joyfully patterned. A painting of the poetess whose poem impressed us all at Biden’s inauguration, in her iconic yellow coat and red headband is now at Harvard. (Figure 22) Seven years ago, Jill Biden wore an African print dress to a White House dinner. It had been designed and made in Africa. As the woman who ran the workshop that employs African women who to become tailors, said about Jill Biden’s decision to buy an African designed/African made dress, (Figure 23) “A woman anywhere in the world, you see–no matter the continent, no matter the color–what she chooses to wear is supporting what another woman is doing in her country”. And how sweet is that, somebody ‘Woke’ finally representing Americans at home and around the world. (Figure 24)

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Figure 22. Portrait of Amanda Gorman by Raphael Adjetey, 2021

Figure 23. Jill Biden in African designed / African made dress, 2014

Figure 24. Melania Trump in ‘I really don’t care, do u’ jacket, 2018

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved