Americans Saving Lives, one life at a time

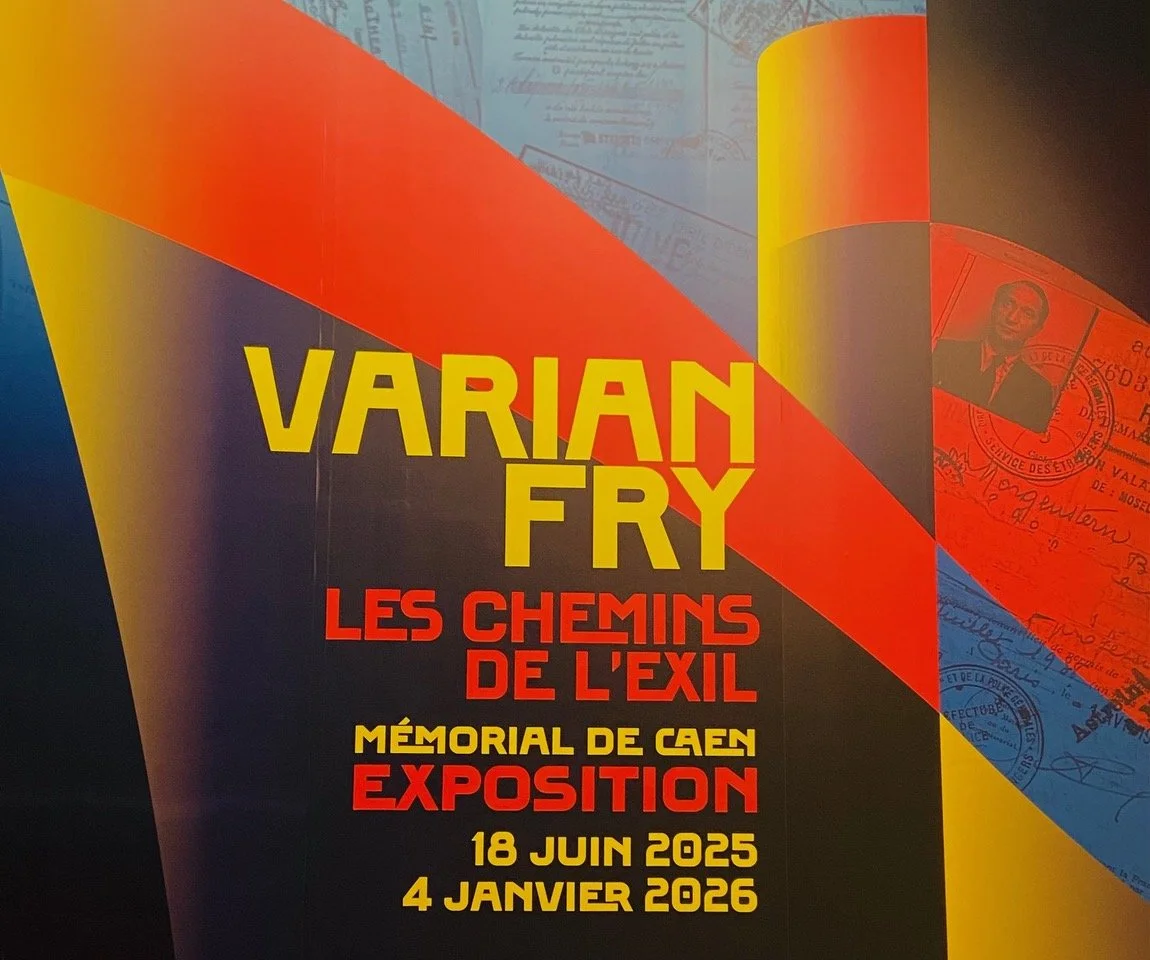

Varian Fry Les Chemins d’Exil. Memorial de Caen (through December 2025)

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. I hope all of you who celebrate Thanksgiving had a wonderful one. And that you are now enjoying, as I am, the joy of leftovers, which have the power to transform one night’s excess into a week of sometimes tasty, but always refrigerator emptying, meals.

As I was thinking about the story I am going to tell you today, I saw a lovely film on PBS, called the Great Escaper. It stars Michael Caine as a 90 year old D-Day veteran making his way, alone, to the beaches of Normandy, to participate in the 70th anniversary of the landing. This week’s story takes place a little before D-Day, before Americans troops joined European forces to overcome the evil that was Hitler.

The Great Escaper was a true story and so is the one I am going to tell you today. About an American who stood up for what he believed and did the right thing, long before his country did. To learn about this American hero, we’re in Normandy, in Caen, at the Memorial Museum, which commemorates World War II. I cannot tell you why I thought I didn’t need to book for this museum. Alas, the place was packed. Of course it was! We were there in early August. The museum is a bit of a mess and a maze. Some exhibitions are free to visit and others require a ticket. It’s difficult to know which is what. Except by trial and error. If you go someplace and nobody stops you, you’re good. If you’re stopped, not so good. There are exhibitions that can be visited as part of the ‘visit everything’ ticket or with a separate ticket. And that’s how, even though Nicolas didn’t get to see most of the stuff he wanted to see, I got to the exhibition I wanted to see. On Varian Fry.

Have you heard of Varian Fry? I first read about him when I was doing research for an article on Dina Vierny, Aristide Mailllol’s model and muse. During the war, she helped people escape from southern France into Spain using a route that Maillol showed her, along which he had a studio where people could sleep before they continued on their arduous way. Dina said she was a member of the American Rescue Center, an organization set up by the American journalist Varian Fry, to help intellectuals and artists flee Vichy France. Years later when Fry was writing a book about the Center, he could not find any records to confirm Dina’s participation. He wrote and asked her if she had any proof. Dina never replied. Fry had to conclude that he couldn’t include her in his book. That she may have helped people but not with his group. Since then, I’ve wanted to know more about Fry and how he saved people from being rounded up and deported.

The exhibition at the Memorial in Caen is a variation of an exhibition that was organized 30 years ago by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. According to the curator of that exhibition, Susan W. Morgenstein, “During the development of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, there was much discussion about which special exhibitions would premiere with the opening of the museum. I pleaded the case for an exhibition about Varian Fry … No one had heard of Fry. But I won the argument, perhaps because he was an American who performed heroically during a dark period for the United States… The result was the exhibition “Assignment Rescue: The Story of Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee.”

Since then, a version of the exhibition has opened in various places, among them, the Jewish Museum in New York and the Holocaust Museum in Houston. In New York, the “installation recounted the daring mission of Varian Fry … who was responsible for rescuing some 2,500 Jews and opponents of the Nazis, including … Marc Chagall, Hannah Arendt, Max Ernst, and Jacques Lipchitz.” In Houston, the exhibition was shown in conjunction with an exhibition called, “How Modern Art Escaped Hitler: From the Holocaust to Houston,” featured works in Houston art museums by artists saved by Fry.

The exhibition in Caen comes with this reminder, “(T)his exhibition traces the extraordinary courage of Varian Fry,..(t)he American journalist (who) managed to obtain numerous visas for European artists and writers threatened with deportation….The exhibition’s organizers aim to shed light on this little-known episode of the war and to remind us of the importance of resistance in the face of barbarism in every era, especially our own.”

Varian Fry was born in New York City in 1907. His upbringing was comfortable but it wasn’t without problems. For two years, he attended Hotchkiss, the prestigious boys boarding school. When he complained about the hazing, he was targeted for even more humiliation. He went elsewhere for his final two years of high school. At Harvard, he founded a literary quarterly with a friend and then had to repeat his senior year because of (an unspecified) prank!

In 1935, at the age of 28, while working as a foreign correspondent for an American publication, Fry was sent to Berlin where he saw first hand the Nazi abuse of Jews. He became a vocal critic of the Nazi regime and wrote about it when he returned to the United States. But the United States wasn’t ready to listen to him.

In 1940, the Emergency Rescue Committee was founded in New York City by members of various American intellectual circles and included Eleanor Roosevelt. The Committee’s mission was to assist artists, writers and scholars threatened by the Nazis, to emigrate to the United States. The Committee’s hope was that the people they saved would come to the United States and enrich the country with their presence.

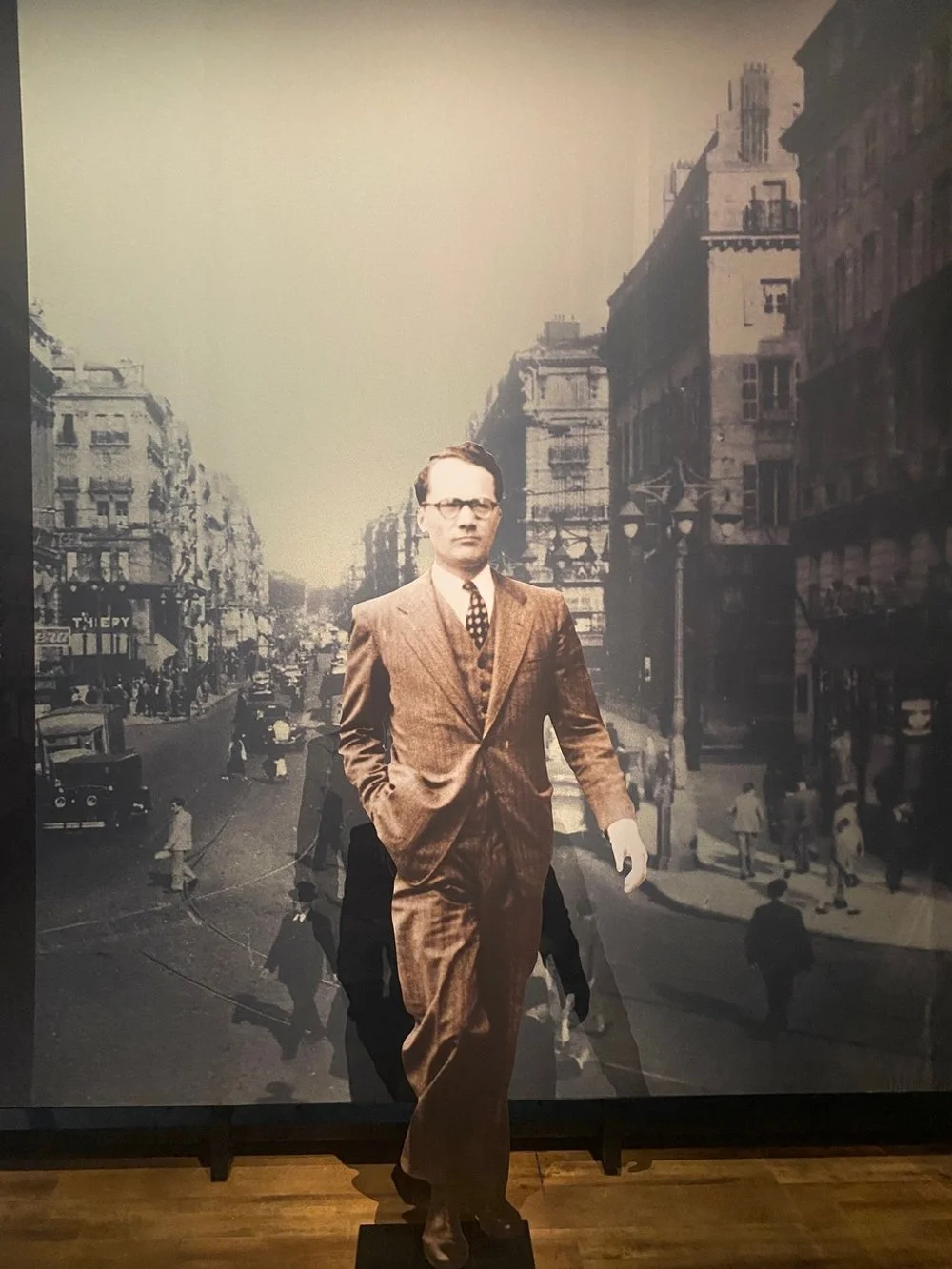

Varian Fry was not a member of the Committee when he volunteered to go to Marseilles in 1940, to find and help the people the Committee hoped to save. He arrived in October with a residence permit valid for three months, 3,000 dollars taped to his leg and a list of two hundred or so names, of mostly well-known artists, writers and thinkers - all stuck in the South of France, where the Vichy government had agreed to “surrender on demand” anyone on the Gestapo’s lists.

On his arrival, Fry gathered around him a team of dedicated and talented expat Americans and European refugees. The group’s “legal” front was an humanitarian aid organization, a cover for the activities in which the group actually engaged - forging documents, getting people out of detention and leading people out of France.

Varian Fry’s team included the wealthy American heiress Mary Jayne Gold who not only provided financial backing but also forged documents and went on dangerous missions, as for example, “persuading a Nazi-sympathizing camp commandant to release prisoners who had been targeted by the Nazis.”

Also on Fry’s team were Charles Fawcett, the American adventurer, actor, and resistance fighter and Richard Ball, known for his effectiveness in securing false documents and exit visas, often from the black market. Among the non-Americans on the team was the German intellectual Albert Hirschmann, who went on to have an exemplary career in America as an economist and author of influential books on political economy and political ideology.

Here is one of the draconian laws that were put in place the month Fry arrived. The Vichy government issued a "Statute of the Jews,” officializing the segregation of all Jews, no matter where on French soil they were found, no matter where in the world they were from. In addition to French Jews and Jewish refugees from everywhere else, Spanish refugees fleeing civil war were targets. As were resistance fighters and political opponents, whether they were communists, socialists or union activists. All were considered dangerous, all were to be captured, detained and interned.

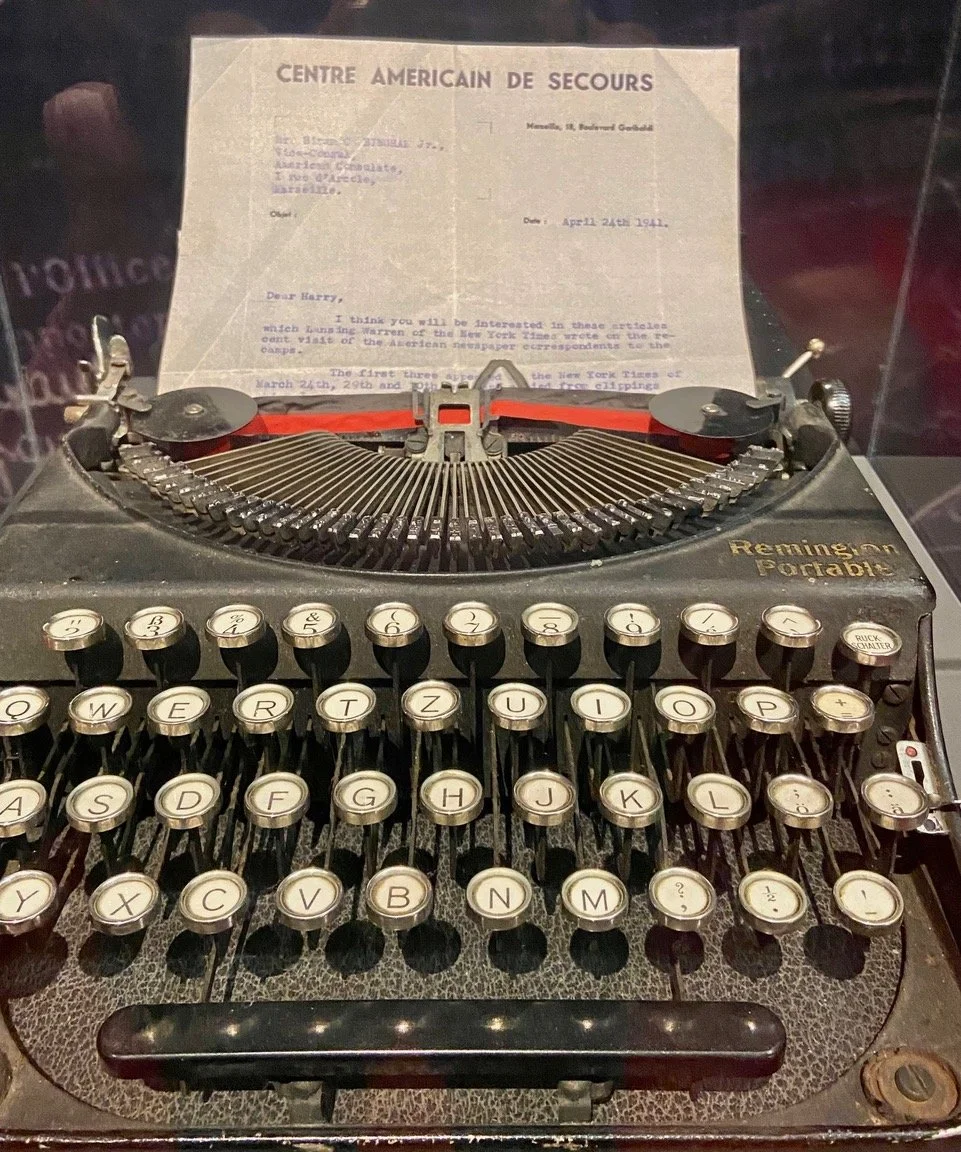

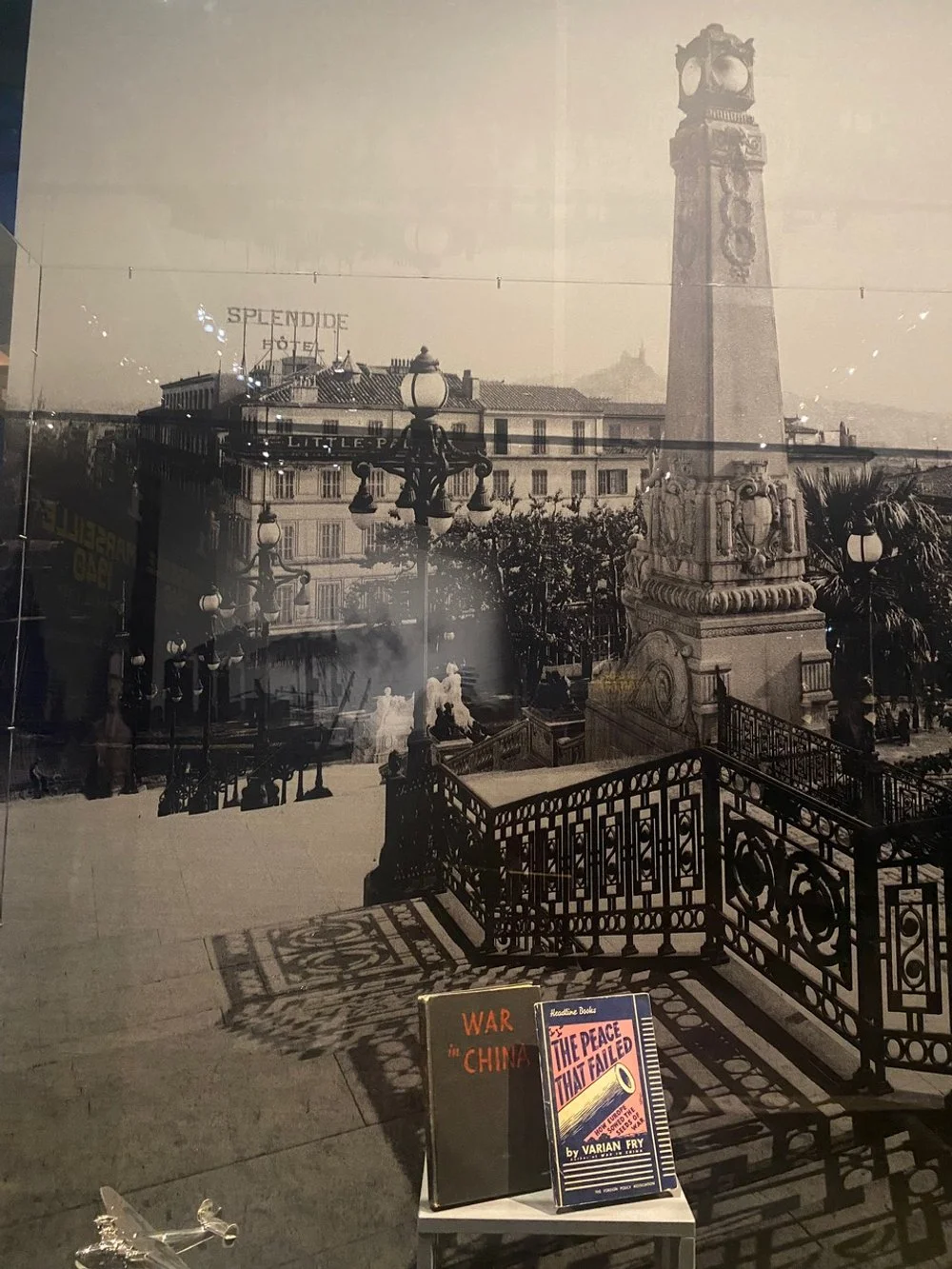

When he first arrived in Marseilles, Fry worked out of his hotel room at the Hotel Splendide. Where he was inundated with people desperate to flee France. Fry’s hotel room quickly became too small and he moved the group’s activities to a 3-room apartment on Rue Grignan, which they quickly outgrew. Fry and his helpers relocated to 4 large rooms at 18 Boulevard Garibaldi, which was also too small for their activities.

The headquarters CAS eventually found by chance was an old bastide (grand country house) in the outskirts of Marseille called Villa Air-Bel. It suited CAS’s needs perfectly - with 18 bedrooms, a large sitting room, a big library and a huge kitchen. The times may have been desperate but the artists and writers who took up temporary residence as they waited for Fry and his staff to organize their escapes, transformed the villa into an artistic community. Ironically, most of the artists were associated with Surrealism, “a movement born of the First World War, which found in dreams, poetry and the unconscious the answer to society's rationalism.” They “exalted love, friendship and freedom.” Inspired by Freud, they experimented with dreams, visions, hypnoses and automatic writings. Their irreverence was the antithesis of Nazism. Their creativity was “a form of insubordination,”“a symbol of art and culture's opposition to totalitarianism.”

If the situation these writers and artists were in wasn’t so desperate, it would be funny to think that the discipline required to get them out of harm’s way was antithetical to their philosophies. As one committee member remembered it, trying to get these writers and artists to do anything was nearly impossible. It was, he said, like herding cats.

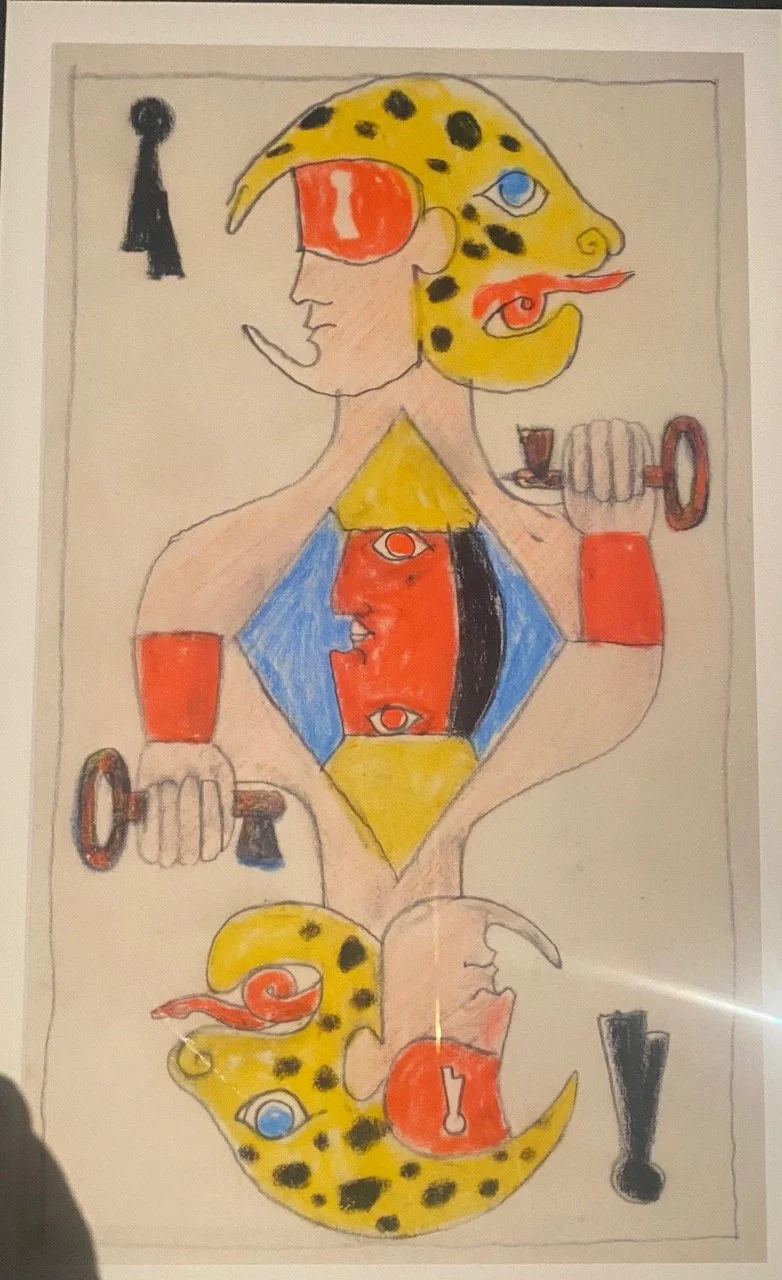

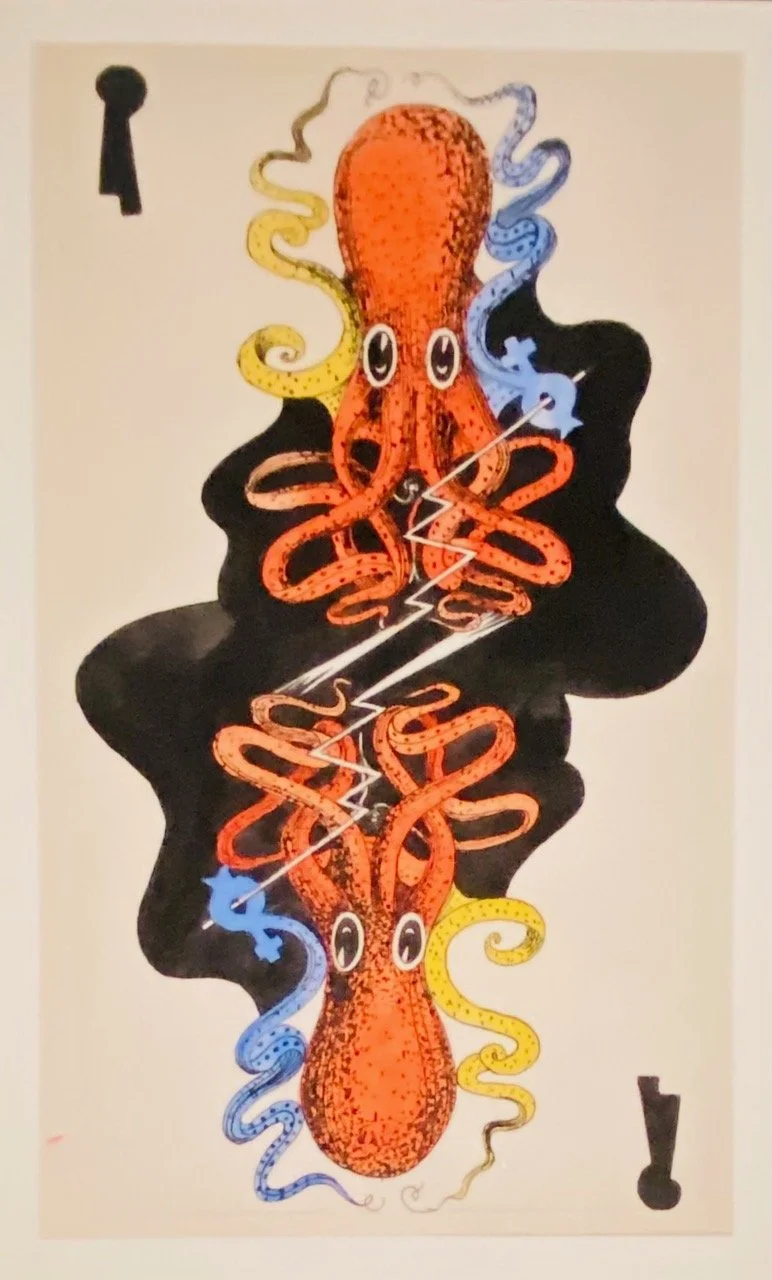

The artists and writers staying at the Villa renamed it, Château Espère-Visa (Chateau Hope for Visa). As they waited, they organized “parties, games and auctions. They invented a surrealist card deck called the Jeu de Marseilles which consists of 20 watercolor-illustrated cards, with the heart, spade, club and diamond replaced by Love (a flame), Knowledge (a lock), Dream (a black star), and Revolution (a bloody wheel). The King, Queen and Jack were replaced with Genius, Siren, and Mage, which all had equal value. Invented in 1941, the deck was published in 1943, and again in 1983.

The curators write that the people staying at Villa Air-Bel turned it into a “festive, creative phalanstery.” Which was a word I didn’t know but which perfectly describes what this group of free-spirited artists did. A phalanstery is a concept developed by the 19th century French philosopher, Charles Fourier. It is a utopian community that combines living and working in a single, self-contained building…The idea is to create a society free from repression, where work is pleasurable and wealth is distributed equitably.

Among those who passed through Villa Air-Bel on their way to freedom from harm in France was André Breton, the French writer and poet, considered the father of Surrealism. Varian Fry obtained visas for Breton, his wife and child for New York in 1941.

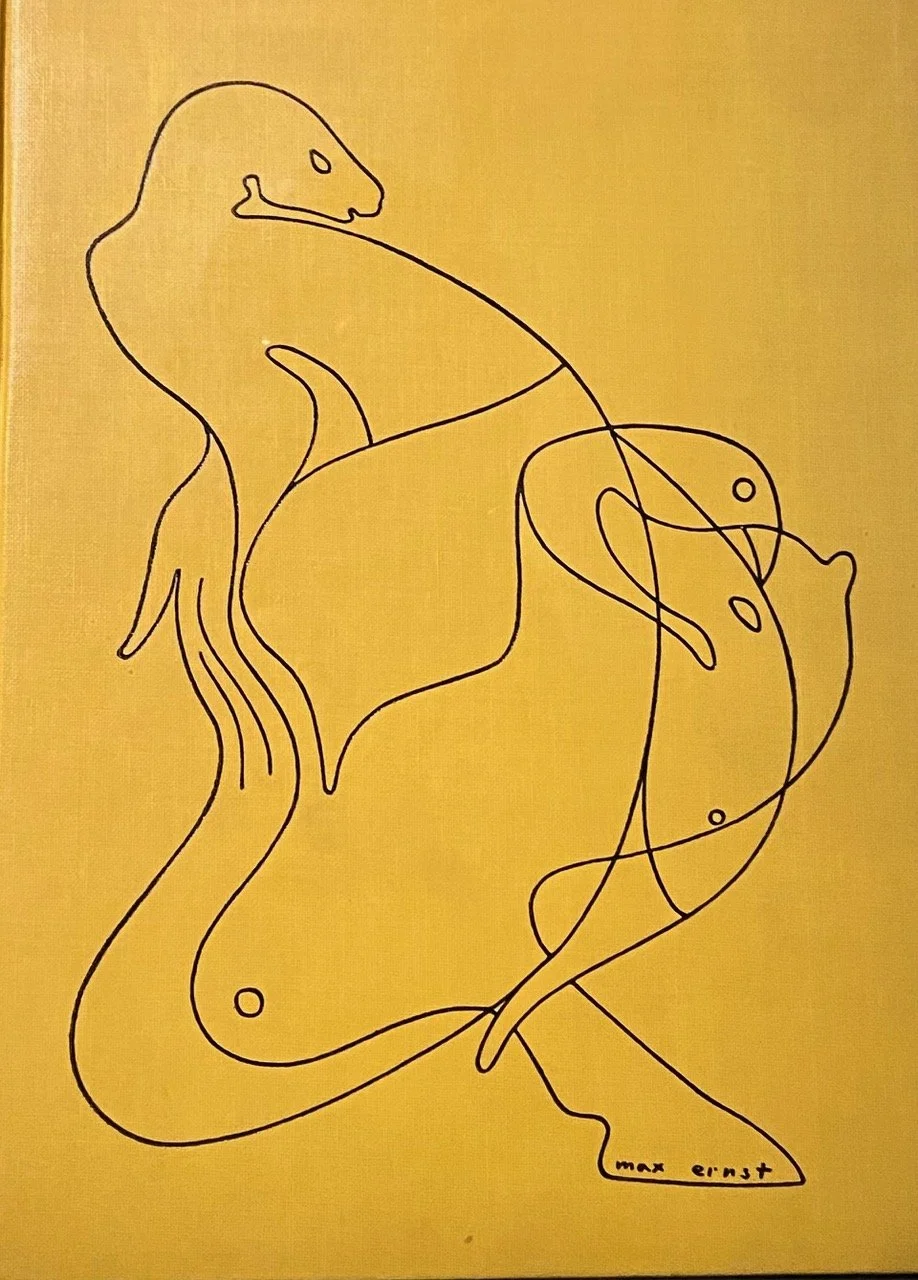

Max Ernst, a German-born painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet was also at Villa Air Bel. Conveniently, his escape to America was made easier by the fact that he was married to the heiress Peggy Guggenheim. She put her “resources, network and personal commitment” at the disposal of Varian Fry’s committee. In 1942, when she was back in Manhattan, Guggenheim opened a "research laboratory for new ideas" in her Manhattan art gallery, the Art of This Century Gallery. Her gallery was where artists in exile could get together and where young American artists could meet their European models.

The American intellectuals who initiated the idea of helping European artists escape Nazi controlled France and emigrate to America, were right. As the exhibition in Caen notes, “the arrival of artists who had fled Nazi persecution had a profound impact on American painting.… European artists brought cubism, expressionism and surrealism along with them in their suitcases. Their move heralded the relocation of the artistic center of the avant-garde from Paris to New York.”

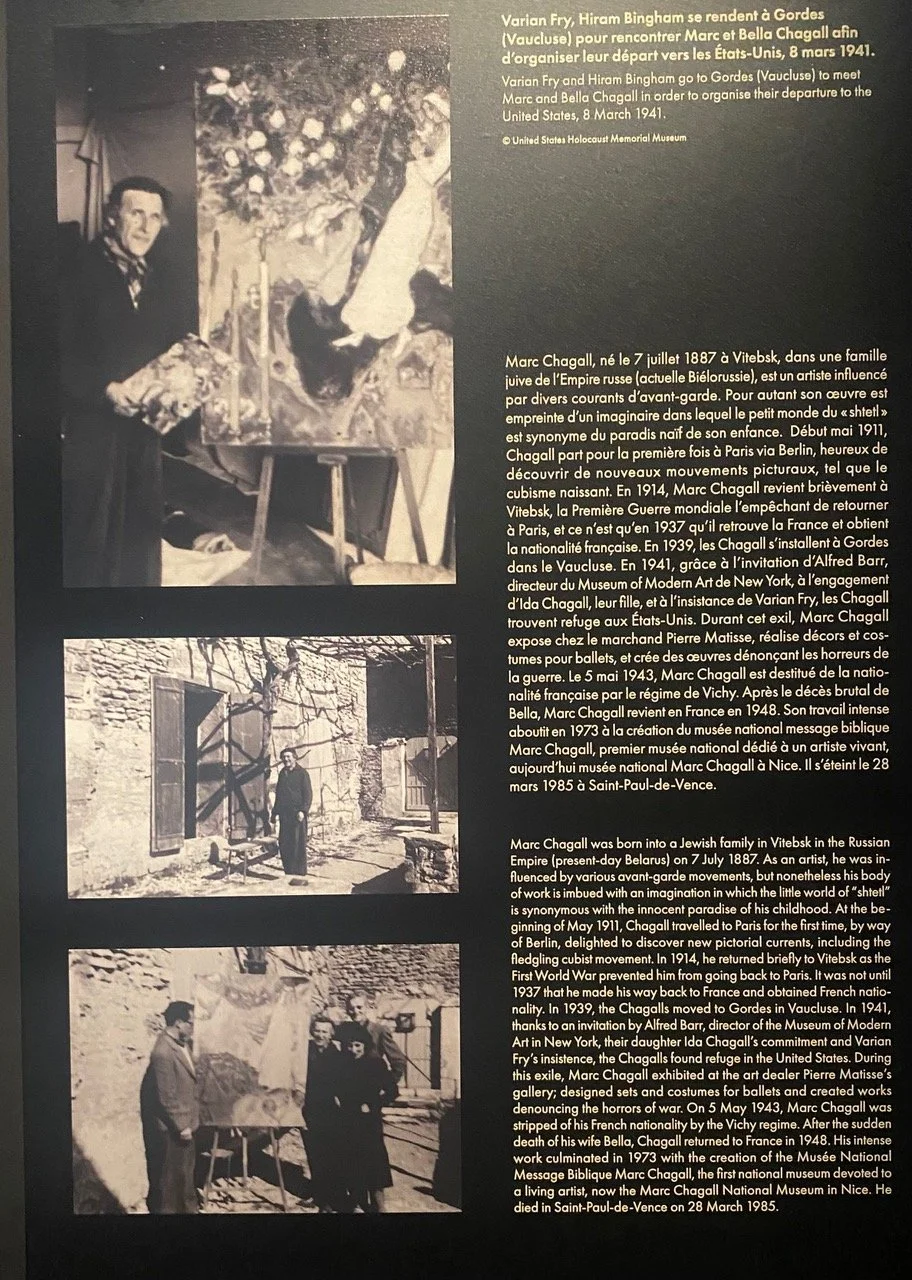

Marc Chagall, the Russian artist associated with the École de Paris and his wife, Bella stayed at Villa Air-Bel as Fry secured visas to America. Same with André Masson, a French artist whose work was condemned as degenerate by the Nazis. The list is long of those who sought and were given help by Fry’s group.

One artist on Fry’s list before he left the United States was Henri Matisse. But Fry was unable to convince Matisse to emigrate, even though his son Pierre was already in New York. After Fry left, Matisse’s ex -wife and his daughter, Marguerite, who both worked for the French underground, were arrested and tortured but eventually released. (Figs 1 - 19)

Figure 1. Centre Americain de Secours, the organization Varian Fry founded when he arrived in Marseilles

Figure 2. In the background the Splendide Hotel where Varian Fry first received people eager to flee Europe

Figure 3. The red triangle that Political deportees had to wear in detention, as Jews wore yellow Star of David

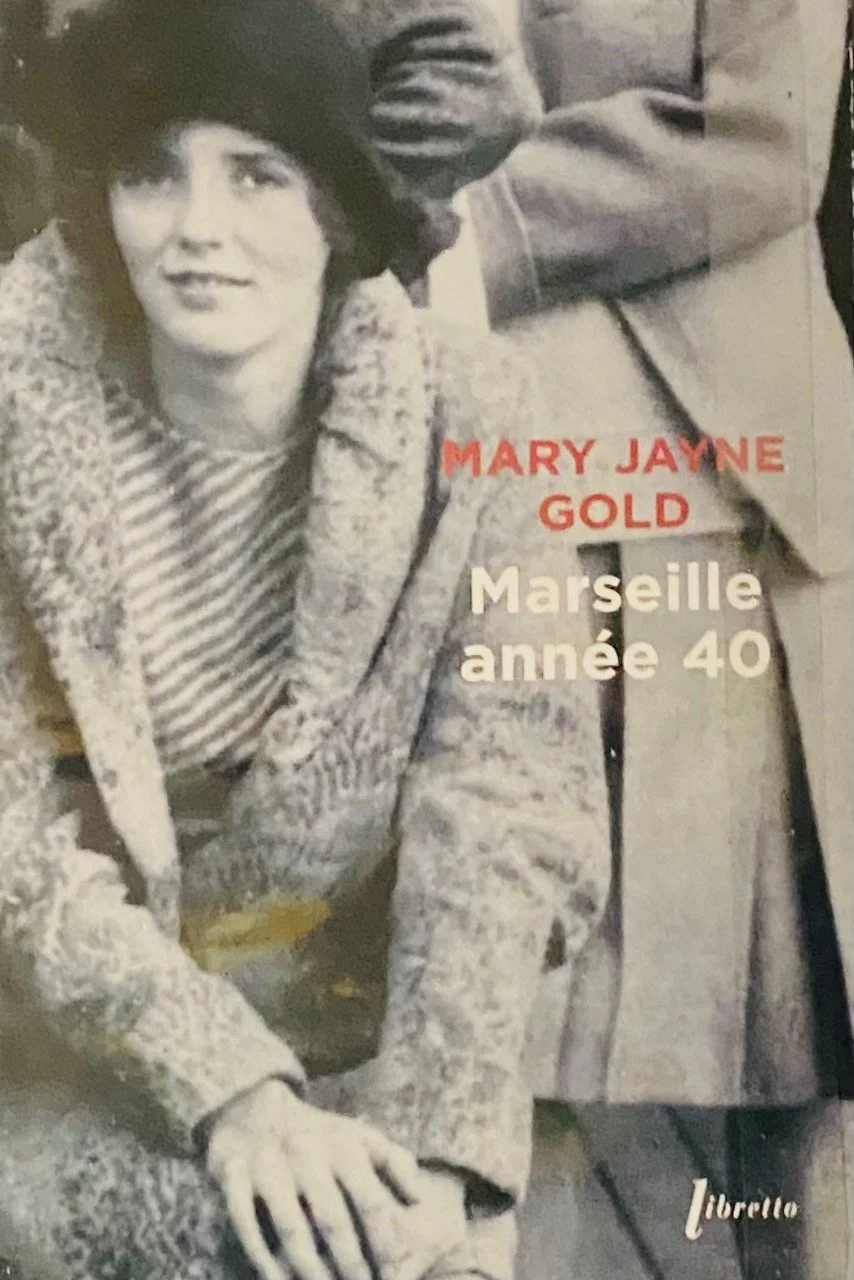

Figure 4. Mary Jayne Gold, the wealthy heiress who, instead of going home, stayed to help Fry help others

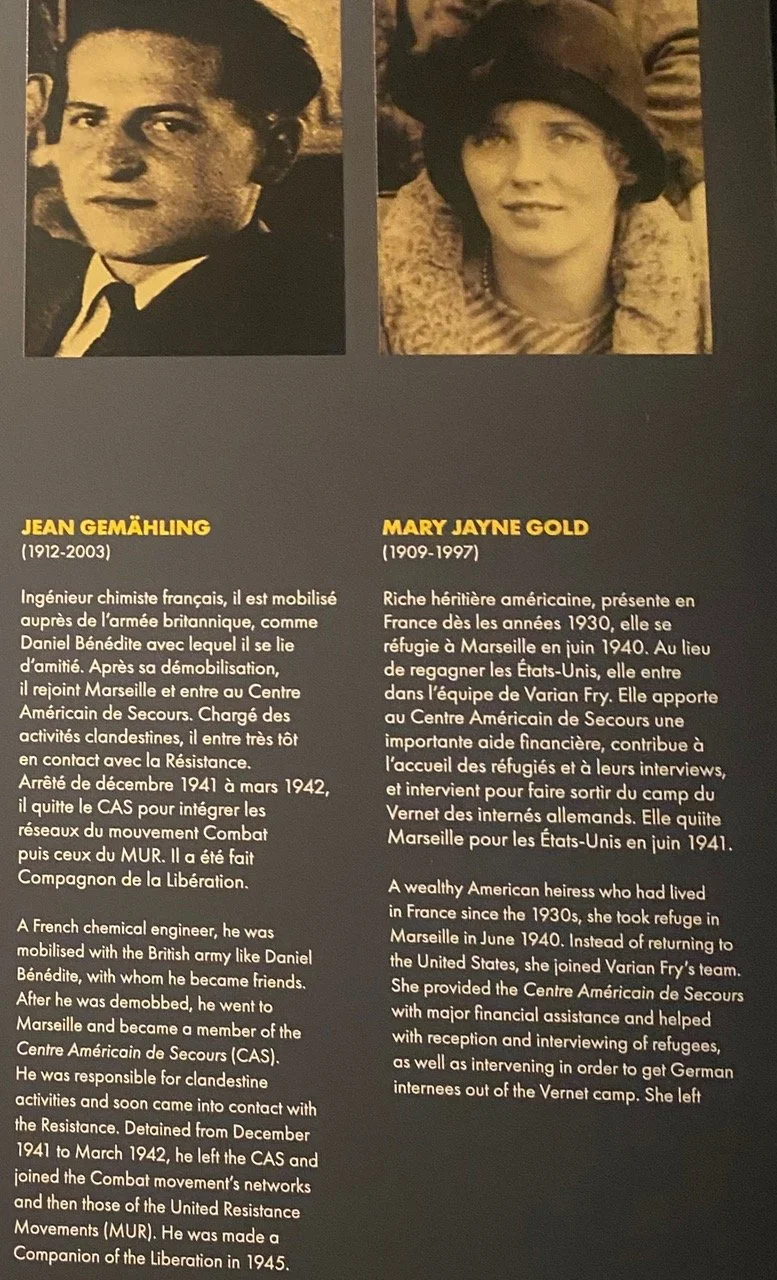

Figure 5. Two of the people who helped Varian Fry, Jean Gemahling & Mary Jayne Gold

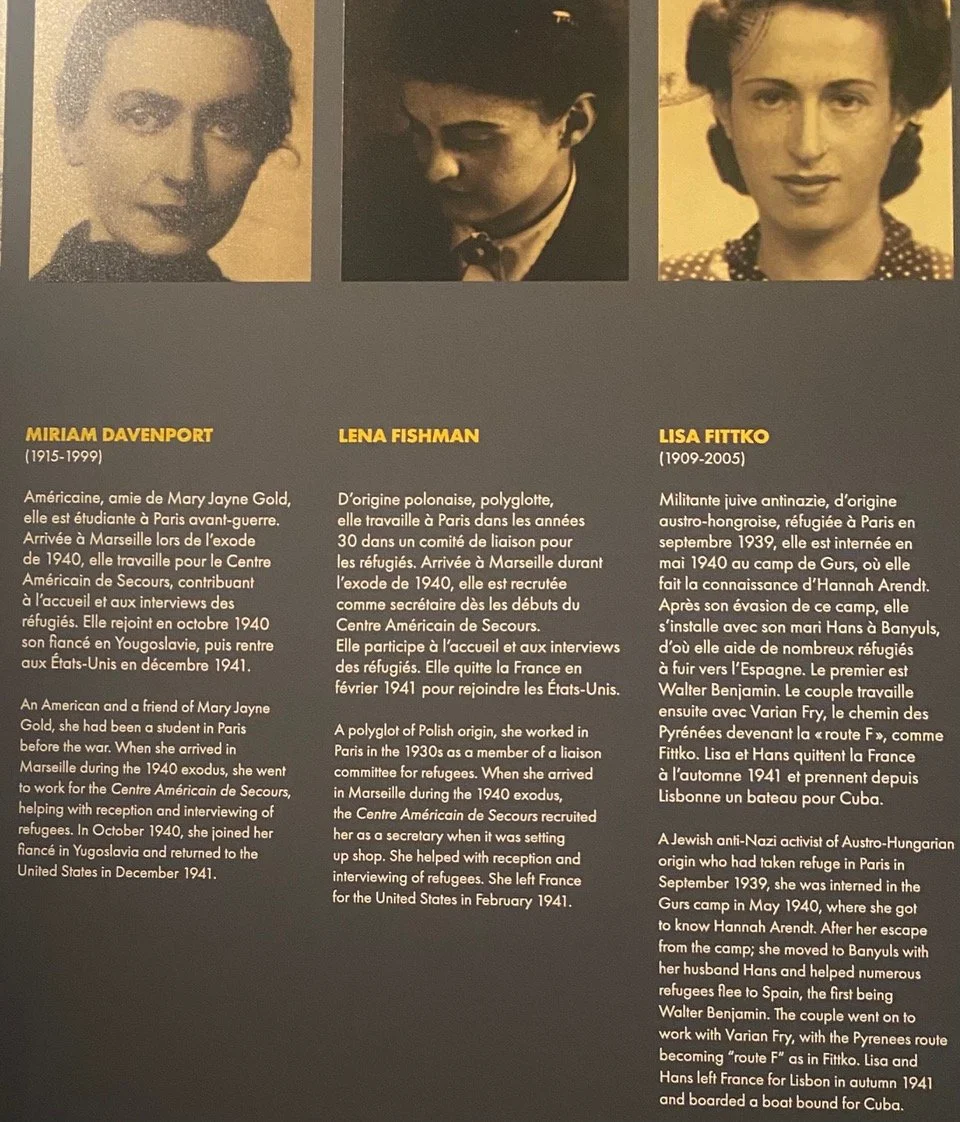

Figure 6. Three more people who helped Varian Fry, Lisa Fittko guided people over the Pyranees into Spain

Figure 7. Villa Air-Bel, outskirts of Marseilles. Here CAS staff and people they helped leave, stayed

Figure 8. Some of the people who stayed at Villa Air-Bel, which they renamed Chateau Espere Visa (hope for a visa)

Figure 9. Varian Fry visited Marc Chagall in Gourdes and convinced him and his wife Bella to emigrate to America

Figure 10. Varian Fry went to Nice to convince Matisse to emigrate but he decided to stay in France

Figure 11. Some of the people Varian Fry and his group helped flee Nazi controlled France

Figure 12. Jeu de Marseilles, 1941 by artists who were staying at Villa Air-Bel, aka Chateau Espere-Visa

Figure 13. Card from Jeu de Marseilles, 1941

Figure 14. Card from Jeu de Marseilles, 1941

Figure 15. Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst at her Art of this Century Gallery, New York

Figure 16. Art of This Century, exhibition cover, Max Ernst

Figure 17. Art of This Century exhibition by European artists who emigrated to United States installation

Figure 18. Art of This Century exhibition installation

Figure 19. Series of lectures given by Varian Fry after his return to the United States

The Romanian surrealist artist, Victor Brauner found a brief respite at the Villa Air Bel. Brauner, a Jew, was born in Romania, He studied art in Bucharest but his paintings were considered too anti-academic. He fled the rise of fascism in Romania and moved to Paris in 1930. Impoverished, he returned to Bucharest but had to leave again when the political situation further deteriorated. In France, in 1938, he went into hiding to avoid the Nazis. His strong ties with the Surrealists led him to Villa Air-Bel where he stayed from time to time. He was Villa Air-Bel's last resident. Unable to get a visa to get out of France, he went back into hiding until the end of the war.

It might have been fun and games at the Villa but the real world and its real dangers were never very far way. People who wanted to leave needed transit visas through Spain so they could get to the port in Lisbon, Portugal. And they needed entry visas to wherever they were being sent. But first, they needed to get out of France. There were numerous routes. One of the main itineraries was the trail that led from Banyuls, France (where Maillol and Dina Vierny were) to Portbou, Spain. Fry needed guides. Lisa Fittko and her husband Hans, German/Austrian anti-Nazi activists, were two guides who led people across the Pyrenees into Spain. The Fittcos were so crucial to Fry’s rescue network that he called their route, the F (for Fittko)-Route. The first time Lisa Fittko led a group for Fry, the Spanish authorities at customs control ordered the group to return to France because they didn’t have exit visas. This was a requirement that had never been enforced before and was never enforced again. Alas, in this group was Walter Benjamin, a Marxist literary critic and philosopher. He was desperate to escape France. When they were stopped at the border, rather than risk the possibility of being sent to an internment camp, he committed suicide, after entrusting a briefcase filled with his writings (which has never been found) to a fellow refugee. Walter Benjamin died at the age of 48 in a cheap pension in Port-Bou, Spain. A passage in Paris honors his name and his writings.

With increased surveillance, the authorities made Fry’s work increasingly difficult. On 15 August, when Fry requested a visa for Spain and Portugal, the authorities told him to purchase a one-way ticket to the United States. When his American passport expired, the State Department would not renew it. When he was arrested by the Vichy, he was told that it was at the behest of the United States government. When Fry was summonsed to police headquarters, he was told that he had to leave immediately. A police inspector escorted him to the Spanish border. After a month in Lisbon, he returned to the United States in October 1941, a little over a year after he first arrived.

During the year of its existence, over 6,000 people were received at the Centre Américain de Secours, 800 names were cabled to the Emergency Rescue Committee to request visas, 600 people were provided with financial assistance and more than 400 parcels containing woolens, blankets and food were sent to French internment camps.

Fry received no hero’s welcome when he returned. Nobody in the United States government wanted to hear about what he seen, learn about what he had done. All of the accolades and awards Varian Fry received were well after the war was over. The first and only one during his lifetimes was from France. He was appointed Knight of the Legion of Honor on 12 April 1967. Thirty years later, in 1996, Fry was the first American to be honored by Yad Vashem (Israel's official institution for commemorating the victims of the Holocaust) as a "Righteous among the Nations” (non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust). (Figs 20, 21) Biographies have since been written about Fry as has a history of Villa Air-Bel. In 2023, Netflix released a series called Transatlantic, about Fry, the people who helped him and the people they helped. The message is clear, it is hard and sometimes dangerous to do the right thing. But we all must. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 20. Varian Fry’s was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor on 12 April 1967, the only honor he received during his lifetime

Figure 21. In 1996, Fry was the first American to be honored by Yad Vashem (Israel's official institution for commemorating the victims of the Holocaust) as a "Righteous among the Nations” (non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust).