So What Did You Do During the Confinement?

David Hockney’s Year in Normandie

There are two temporary exhibitions currently on at the Musée de l’Orangerie. Today I am going to talk about David Hockney’s exhibition, A Year in Normandie, which is perfectly suited for the Orangerie. Home to eight huge Water Lily paintings by Claude Monet. A subject which he painted at different times of day, at different times of year, for 40 years. The artist gave the paintings to France at the end of the First World War to provide comfort to a battle weary country. In much the same way, David Hockney’s paintings of the seasons as they unfolded over the course of a year around his Normandy farmhouse provide succor for our pandemic weary souls.

"When the lockdown came in May 2020, the Olympics were canceled but I realized that they couldn't cancel the spring ... And the spring that year was really wonderful," David Hockney (2020).

David Hockney is the Man of the Moment. He has been popping up everywhere lately. With exhibitions in Manhattan and London and a short video, “Remember you cannot look at the sun or death for very long” on view in those places as well as Tokyo, Seoul and Los Angeles. And now he’s back in Paris, at the Musée de l’Orangerie until Valentine’s Day, 2022 (video included).

Exactly one year ago, after museum doors had been bolted tight but before galleries were shuttered, too, Erin and I met in front of the Galerie Lelong on rue de Téhéran (where I hoped that I didn’t look TOO American).

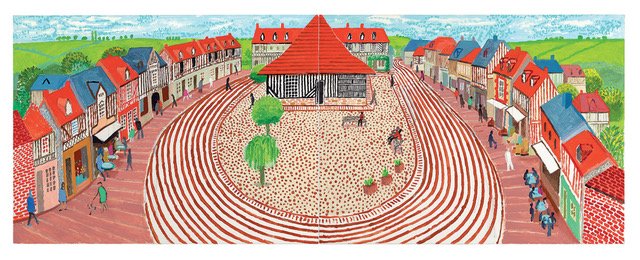

We were there to see an exhibition of Hockney paintings, which I wrote about From iPads to Scrolls. I loved that exhibition, called 'Ma Normandie,’. Especially the paintings of the little village square of Beuvron-en-Auge, all red stripes and red dots against a white background. With little figures walking past shops or seated at tables maybe covered with cloths. (Figures 1 & 2)

Figure 1. Village Square, Beuvron-en-Auge, David Hockney, 2019

Figure 2. Me & Rodin in front of Musée de l’Orangerie, dressed for Beuvron-en-Auge

So, when I read that Hockney would have a second exhibition, on the same subject, at a museum this time, I was surprised. But when I went to the Orangerie, I understood. This is a completely different exhibition. These paintings are delightful evocations of the Bayeux Tapestry (really an embroidery) (Figure 3) and Chinese scroll paintings (Figure 4). Both of which were Hockney’s inspiration in Normandy, but which were only hinted at in the exhibition I saw last year.

Figure 3. Bayeux Tapistry, (embroidery) Bayeux, France,after 1066

Figure 4. Chinese Scroll Painting, 1222

David Hockney, to refresh your memory, was born in 1937 in Bradford, England. (Figure 5) A city that rose to prominence during the 19th century as a center of textile production, thanks to the easy availability of coal. As Hockney recently told a correspondent for the Guardian, when he was growing up in Bradford, it “was a very, very black city…The buildings were totally black from coal. ….”

Figure 5. David Hockney, self portrait, 2003

I know what Hockney is talking about. I grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. By the time I was born, laws to curb the use of coal had been passed but I think not yet implemented. Pittsburgh was a gray city, a sooty city.

Is it possible that Hockney’s entire life trajectory can be credited to coal and air pollution? Maybe. Probably. As soon as he could, Hockney fled England for sunny Southern California. Where he mostly stayed for forty years. (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), David Hockney, 1972

But he was seduced back to England by …. well, by seasons, of course! As Hockney remembered, “The first spring I’d seen in 20 years was in 2002, I walked every morning through (London’s) Holland Park. I noticed the spring and I thought: ‘Oh, it’s very exciting, this. Very exciting.’”

I can relate. San Francisco, where I have lived for most of the past 40 years is, like Los Angeles, season-less. It’s a balmy 65 degrees all year long. Pittsburgh winters were brutal. But in San Francisco there are no natural markers for the passage of time. No buds on the trees to signify spring. No crunching leaves underfoot to herald autumn.

As it happened, Hockney found himself in London in October, 2018. At Westminster Abbey for the dedication of a stained glass window he had designed to honor the reign of Elizabeth II. After the festivities, he didn’t want to go right back to L.A. and he didn’t want to stay in London, either. And for some reason, his native Yorkshire did not beckon. So, he and his assistant got into a car and drove to France. Drove because nobody tells you not to smoke in your own car. And that’s how Hockney happened to be in Normandy.

After visiting Honfleur and various other Impressionist haunts and then going to Bayeux to see Queen Mathilde’s tapestry, (embroidery) he felt a new project coming on. He was going to paint the seasons, in Normandy. And for that, he was going to have to stay put for a while. Once again, his requisite pack of cigarettes a day determined the course of events. Better to buy a house than rent one. Rentals come with restrictions, like for example, where and if you can smoke. If it’s your house, it’s your rules. (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Photograph of David Hockney smoking, in Normandy, 2020

The idea of painting the seasons as they unfolded was not a new one for Hockney in 2020. A decade earlier he had done the same in his rediscovered native Yorkshire. He documented its changing seasons with paintings on his iPad and digital videos of the same scene in winter, spring, summer and fall. (Figure 8)

Figure 8. Woldgate Woods in Yorkshire, David Hockney, 2006

That exhibition was modestly called ‘The Bigger Exhibition.’ I saw it in 2014 at the deYoung Museum in San Francisco. The range and depth of the work displayed was astounding. His embrace of the iPad and the video camera were to me, nothing short of miraculous. I was not alone in my enthusiasm. The critic Roberta Smith wrote that the exhibition showed Hockney as “a tradition-fluent progressive working nonstop at the height of his powers, deftly juggling digital and analog modes of representation.”

Of course, what he created - iPad paintings, videos, charcoal sketches could never have been made in Los Angeles. Because unlike L.A., East Yorkshire’s vegetation changed dramatically with the seasons.

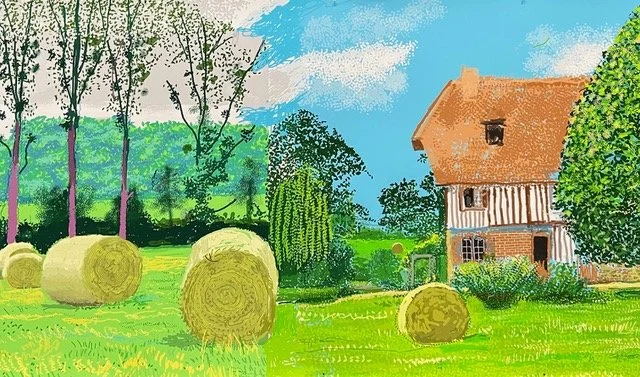

So, if he had already ‘done’ landscape and seasons with his native Yorkshire, how is his Normandy project different? With Yorkshire as precedent, his Normandy focus is more prosaic. Not a forest, just a little house and an outbuilding that was transformed into a studio and some other outbuildings that were left ‘as is’ and the land around it all. (Figure 9) He paints what he can see from the window of his farmhouse or from his porch or his garden. With his dog by his side, he draws and sketches and paints and smokes. For as long as he wants. (Figure 10)

Figure 9.#339, 18 May 2020, David Hockney

Figure 10. David Hockney and his dog, Ruby in Normandie, 2020

How is Hockney’s exhibition like the Bayeux Tapestry? Well, with both, as you walk along, you see a story unfolding. One is a sequence of human events that led up to the Battle of Hastings and concluded with the victory of the Normans over the English. The other is a story of nature, the passage of time from one season to the next. (Figures 11, 12) In both, details provide clues to habits and customs, military uniforms and weapons for one, architecture and planting for the other. (Figures 13, 14)

Figure 11. Bayeux Tapestry

Figure 12. A Year in Normandie, David Hockney, 2020

Figure 13. Battle of Hastings, Bayeux Tapestry

Figure 14. A Year in Normandie, Winter, David Hockney, 2020

And how is it like a Chinese scroll? As a scroll is unfolded, its story is revealed. It is viewed sequentially, in sections. Hockney’s scenes unfold as we walk along. We see the same landscape but as the seasons change, each repeated motif is different. The trees go from buds to blossoms, leaves fall to the ground and are replaced by bare branches, stark and snow covered.

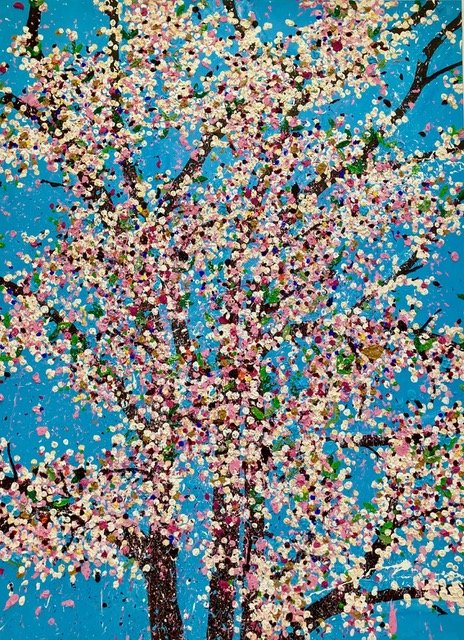

As I looked at the summertime scene of trees in full bloom, I thought immediately of Damien Hirst’s painting series at the Fondation Cartier. Both artists celebrate what Hirst calls the almost ‘tacky’ abundance of pink and white and red blossoms. Thick blooms on the tree, thick pigment on the canvas. (Figures 15, 16)

Figure 15. Cherry Blossoms, Damien Hirst, 2019

Figure 16. A Year in Normandie, David Hockney, 2020

I found Hockney’s images particularly moving because I know the changes he documents. I have had a ‘ring side seat’ to mark those passages of time in the French countryside. The French café chairs and table that are in Hockney’s garden, are in my Dordogne garden, too. (Figures 17, 18) The rolls of hay that Hockney depicts are the ones the farmer makes in my field every year. I don’t pay him to mow my fields. He doesn’t pay me for the hay he rolls and feeds to his cows and sheep. (Figures 19, 20) How many times have I walked or driven by my neighbors’ homes and seen stacks of wood placed exactly like this one alongside Hockney’s grange (barn), (Figure 21, 22). Begun in the heat of summer and added to all autumn for the long winter ahead.

Figure 17. A Year in Normandie, detail chair, David Hockney, 2020

Figure 18. My little courtyard, Petit Bout, Dordogne

Figure 19. A Year in Normandie, detail hay, David Hockney

Figure 20. My Hay, Petit Rousset, France

Figure 21. A Year in Normandie, detail stacked wood, David Hockney, 2020

Figure 22. Real Stacked wood, 2021

How brilliant is it that the exhibition is at the Orangerie where your ticket also includes a visit to Monet’s Nymphéas. Here is Hockney on Monet, “Monet saw 40 springs, 40 summers, 40 autumns and 40 winters in Giverny. They’re fantastic paintings. They’re still very, very fresh… They could have been painted yesterday.…”

Monet gave the paintings that hang in the Orangerie (Figure 23) to the French state after the tragedy that was the first world war. A century later, Hockney has shown again that nature, painting it, looking at it, is perhaps the only reasonable response to a crisis. Hockney’s assistant calls these paintings “the Covid collection,” not to make light of the suffering of so many but as a celebration of the tenacity of nature.

Figure 23. Les Nymphéas, Claude Monet, 1922

As so many creatives have noted, the lockdown, the confinement, the standstill, was a gift of time. Says Hockney,“I had a wonderful time, I worked long hours. I’d go to bed at 9 o’clock sometimes – and sometimes it was still light when I went to bed. But I loved getting up early in the morning, like Monet did.” (Figure 24)

Figure 24. David Hockney and A Year in Normandie, 2020

So much was taken away during the pandemic. But the earth continued to rotate around the sun. The seasons continued, one after another, one into another, as they always have. If confinement was like a game of musical chairs, when the music stopped, David Hockney got one of the best seats in the game. Confined in his new old house in the Normandy countryside, David Hockney painted a frieze on his iPad depicting the constantly changing, unchanging renewal of nature. Our modern world ground to a halt but the natural world did not. The planet kept doing its thing. The A Year in Normandie exhibition is a reassuring reminder that indeed they cannot cancel spring (or any other season either, for that matter!)

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you