So, what’s wrong with being a mama’s boy?

Proust on his mother’s side: MahJ

The exhibition Marcel Proust Du côté de la mère (Marcel Proust On his mother’s side) at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, is the perfect follow up to the earlier exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet, Marcel Proust un roman Parisien, (Marcel Proust a Parisian Novel). Two of the grandest paintings that were on display at the Carnavalet are here, too. Alas, Proust’s bed did not make the trip to MahJ. (Figure 1) It’s probably one of those things, like the Mona Lisa, that museums just don’t lend.

Figure 1. Proust’s bedroom at Musée Carnavalet

It is a visually rich exhibition with paintings of Venice by Monet (Figure 2) and etchings by Whistler of the same subject. (Figure 3) Those were both in connection with Proust’s obsession with John Ruskin and Ruskin’s obsession with Venice, about which, more later. I thought it was odd that the curators selected Whistler to represent the Venice of Ruskin since Whistler sued Ruskin for defamation in the late 1870s after Ruskin wrote a nasty review of Whistler’s painting ‘Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket’. (Figure 4) Ruskin said about the painting, “I …. never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas (a lot at the time) for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler won the case. But not the cash settlement he expected. Bankrupt, he left for Venice to make his etchings.

Figure 2. View of Venice, Claude Monet

Figure 3. View of Venice, James McNeil Whistler

Figure 4. Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket, James McNeil Whistler

Another section is devoted to Proust’s Parisian haunts. There are the two soirées that were at the Carnavalet (Figure 5) and there are slices of Parisian life captured by Gustave Caillebotte - the details and the views, (Figures 6, 7) emblems of Haussmann’s Paris. Maybe because Édouard Vuillard has been on my mind a lot recently, but it seems that he is especially well represented in this exhibition. And that may simply be because so many of his acquaintances were Jewish. For example, there is a painting by him of Thadee Natanson’s Paris drawing room.(Figure 8) Natanson was the owner of the Révue Blanche for which Édouard Vuillard drew sketches and for which Proust wrote them. Natanson was the husband of Misia, with whom Vuillard was infatuated and who Proust seems to have known quite well, too. There was also a portrait of Lucie Hessel, who actually did become Vuillard’s mistress and whose husband Jos, was Vuillard’s art dealer. Everybody was Jewish but Vuillard!

Figure 5. “Le Balcon” René-Xavier Prinet, 1905-06

Figure 6. A Balcony in Paris, Gustave Caillebotte, 1881

Figure 7. A Rainy Street in Paris, Gustave Caillebotte

Figure 8. A Drawing Room, Édouard Vuillard

A grand painting by James Tissot, is a group portrait of the members of the Cercle de la rue Royale, a gentleman's club founded in 1852. (Figure 9) It was one of the few clubs that accepted Jews as members, about which, more later.

Figure 9. Cercle de la rue Royale, James Tissot

Another section is devoted to the places where Proust summered, mostly on the Normandy coast, like Deauville and Trouville. In this section there are once again, several paintings by Vuillard, as for example, one of his niece, the daughter of his sister Mimi and his best friend, the painter Roussel. Lots of other paintings and drawings and sketches, by Boudin and Monet, Dufy and Helleu (unknown today but one of Proust’s models for the artist Elster), (Figures 10, 11) are gathered here to give us the sense of luxury and ease enjoyed by these wealthy, mostly Jewish people, at their summer homes on the Normandy coast. One painting of this group depicts an elegant couple, relatives of Proust. We learn from the wall text that when the husband was 83 and his wife 67, they were transported to Auschwitz where they were murdered. The Holocaust is never very far away from this museum.

Figure 10. Mme Helleu, Paul Cesar Helleu

Figure 11. Paintings of Deauville and Trouville by Boudin, Monet, Dufy, Helleu

So, lots of paintings and objects, too, give us a sense of the worlds in which Proust moved. The exhibition’s intellectual underpinning is organized thematically. The first theme is the exhibition’s title. To say that somebody is Jewish ‘on their mother’s side’ is moot. Because, in matters of faith, Judaism is a matrilineal society. And so obviously, it is the religion of the mother that determines the religion of her children. Indeed, matrilineal descent has been a fundamental principle of the Jewish people as long as there have been Jewish people. But of course, you would have to accept Jewish law for that to matter. And for European Jews, assimilating into the dominant culture, it wasn’t a rule that they thought applied to them. If the number of baptisms of children born to Jewish mothers and Christian fathers is any indication. Hitler and his henchmen didn’t agree. They had rules about who was Jewish. Petain, when he took power in France, tightened those rules so quickly that many people, like Beatrice Reinach (née da Camondo) who thought she was safe, that is, not Jewish, was picked up and transported to the death camps where she and her children were murdered.

So, in the beginning, in this story, was the Mother, Jeanne Weil. (Figure 12) Whose maternal and paternal families were powerful and rich members of the Parisian Jewish haute bourgeoisie. They prized learning for their daughters as well as their sons. Since girls couldn’t attend lycée, Jeanne was educated at home, by private tutors. She learned to read Greek and Latin and to read and speak English and German. Jeanne’s mother Adele had also been educated in languages, literature, art and music. As preparation for becoming a salonnière in the tradition of Mme de Sévigné who chronicled the comings and goings, the scandals and secrets, of Louis XIV’s court. And who lived at the Carnavalet before it was a museum! Jeanne’s mother, Adele learned how to host a salon from her aunt Amélia, whose salon she attended regularly. And it was Amélia’s husband, Adolphe Crémieux, (Figure 13) who made time in his busy schedule to tutor Adele. Which is nothing short of amazing since Crémieux is known amongst some groups, as having signed the decree that granted French citizenship to Algerian Jews. And among other groups for encouraging the abolition of slavery in the French colonies and abolishing the death penalty for political crimes.

Figure 12. Jeanne Weil

Figure 13. Adolphe Crémieux

As one biographer wrote, “To Marcel, his grandmother Adèle always seemed ‘more Sévegné than Sévigné herself.” And she passed her admiration for Sévigné on to her daughter and grandson. Sévigné became, for Proust ,’a major literary inspiration for her way of narrating, as a chronicler of her epoch, and as a model of motherly devotion.” In his novel, Proust’s Narrator’s grandmother has the same love for the letters of Mme de Sévigné’ as his own grandmother had.

As we all know, Marcel Proust was a mama’s boy. A parlor game that he played with a friend included a questionnaire. (Figure 14) One of the questions was ‘What is your idea of misery. His answer: his “to be separated from my mother”. That was when he was 15, four years later, he answered the same question this way, “Not to have known my mother or my grandmother.” Proust’s responses were discovered in 1924, in a ‘confession album’ belonging to his friend Antoinette Faure, daughter of future French President Félix Faure. The questionnaire is here, and it might seem familiar to you because one very much like it can usually be found on the back page of Vanity Fair magazine, answered each month by a different celebrity.

Figure 14. Questionnaire

According to Edmund White, when Marcel was a little boy, he couldn’t go to sleep without a goodnight kiss from his mother. But it was never just one kiss, it was more like ten. And he would become hysterical if she refused to keep returning to his bedroom for those bedtime kisses. Proust dramatized this often repeated scene in his masterpiece when the Narrator becomes upset when his mother, who he depends upon to tuck him in and give him one last kiss, over and over again, isn’t able to come to him one evening because she is too busy with her guests. (Figure 15)

Figure 15. Narrator’s mother kissing him goodnight, A La Recherche Graphic Novel

And what about Marcel’s father, Adrian Proust? (Figure 16) We are told that Adrian was extremely intelligent but his education hadn’t included the liberal arts. He knew almost nothing about literature and music. That must have been difficult for Jeanne and awful for Marcel, to have a father with no background, perhaps no sensitivity to what he held dear. Adrian was meant for the priesthood. But after university, he decided to abandon the old god for a new one, science. He became an expert on infectious diseases. In his investigation into the cause of cholera, he concluded that prevention was a possibility. He pioneered the idea of social distancing, quarantine and confinement, which he called “sequestration“. He claimed that by washing his face and hands frequently, he avoided contracting the diseases of his very sick patients. He was a man for his time and a man who made our times easier too, once we accepted social distancing, quarantining, masking and confining.

Figure 16. Adrian Proust, Marcel’s father

As we know, Marcel Proust had asthma. According to the European Respiratory Journal, “Marcel Proust endured severe allergies and bronchial asthma from early childhood. Those who suffer from the frightening and recurrent pangs of asthma often become dependent on their parents particularly their mother; Proust was no exception. In his time asthma was poorly understood by physicians who considered the illness to be a type of hysteria.” His parents differed on how to deal with it. His father told him to “exercise, go outside, open the window,” His mother told him to avoid contamination. So, he covered himself up and eventually locked himself up in a cork lined bedroom. Mother knows best.

In the autumn of 1899, when Proust was in his late 20s, he discovered John Ruskin, the English art critic. (Figure 17) My graduate school advisor was mad for Ruskin. Since I’m more of a ‘get to the point’ kind of girl, I never have been a fan. So, I was especially interested to discover what Proust appreciated in Ruskin, hoping that as art was my link to Proust, so Proust would be my link to Ruskin. Hasn’t happened yet.

Figure 17. John Ruskin

This is how it happened for Proust. He was spending a few weeks with some elegant friends at the elegant French spa town of Évian-les-Bains on Lake Geneva. He wrote to his mother asking her to send him Ruskin et la religion de la beauté, a book written in 1897 by the art critic, art historian and translator, Robert de La Sizeranne, a specialist in English painting and John Ruskin. Rather than waiting for the book to arrive, Proust rushed home to Paris and headed straight to the Bibliothèque nationale where he found a translation of "The Lamp of Memory," the sixth chapter of Ruskin’s The Seven Lamps of Architecture.

As Proust immersed himself in the chapter, two themes emerged - memory and time. Themes that became Proust’s own. Like when Proust’s Narrator, in the library of the Guermantes' Paris residence, says this: “I realized … that the essential, the only true book, … does not have to be 'invented' by a great writer – for it exists already in each one of us – … The function and the task of a writer are those of a translator.” How nice to think that inside each of us is our own book, waiting for us to write it.

When Ruskin died, Proust assumed he would, too. And when he didn’t, he decided it was because Ruskin's soul had transmigrated into him. And that meant, obviously, that Proust should begin transmitting Ruskin's ideas to others. It was a huge responsibility for someone who had been, until then, a superficial, directionless dilettante. Ruskin became Proust's raison d’être, his spiritual and aesthetic guide. Ruskin provided Proust with a philosophy, one that privileged work and sacrifice.

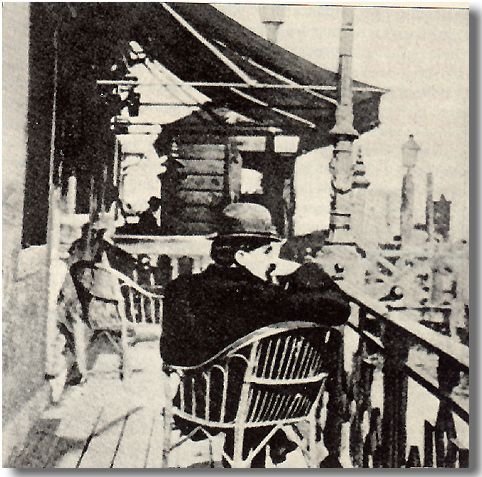

Proust paid homage to Ruskin by reading and memorizing nearly all of Ruskin's works (I don’t know if anyone tested him), by translating two of Ruskin’s books, The Bible of Amiens and Sesame and Lilies, into French. Which his mother had to help him with because her English was so much better than his. And by making pilgrimages to places significant to Ruskin, like the Gothic cathedrals of Rouen, Amiens, Chartres, and Beauvais. And Venice. (Figure 18) Where he and his mother traveled in 1900, the year after Ruskin’s death. From Venice, he made a day trip to Padua to see Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel. (Figure 19) In particular, the Virtues and Vices, en grisailles (painted to look like stone), (Figure 20) on the walls, just below the bands of narratives. They were described by Ruskin in The Stones of Venice and they appear in Proust’s masterpiece, too. Especially the figure of Charity, Caritas. (Figure 21)

Figure 18. Proust in Venice

Figure 19. Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Giotto

Figure 20. Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, detail Virtues & Vices, Giotto

Figure 21. Scrovegni Chapel, Padua Caritas, detail, Giotto

This passage, written by a baptized, non-observant Catholic Jew, reads like a prayer, a psalm, Ruskin replacing the Lord as Proust’s prophet, as his shepherd. Proust wrote, "I had said to myself, in my enthusiasm for Ruskin: He will teach me, for he too, in some portion at least, is he not the truth? He will make my spirit enter where it had no access, for he is the door. He will purify me, for his inspiration is like the lily of the valley. He will intoxicate me and will give me life, for he is the vine and the life.” Cynthia Gamble

But wait, there’s so much more to tell you about - Proust and the Dreyfus Affair, Proust and Homosexuality, Proust and the Ballets Russes and Queen Esther, who makes an unexpected appearance. Next week, promise!

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.