Cleopatra: History / Legend // Myth / Icon

Instititut du Monde Arabe

Cleopatra’s nose

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. As I write this, I am impatiently awaiting Ginevra’s arrival from San Francisco and the start of our long anticipated walk on the West Highland Way in Scotland. Which, if we’re not finished off by the walk, we’ll finish off with visits to Glasgow and Edinburgh. Not one to lallygag, I convinced Nicolas to join me at the Bourse de Commerce the day before he left for China. It’s a rich and wonderful place to experience contemporary art and the various exhibitions on at any one time are well worth exploring. (Figs 1, 2)

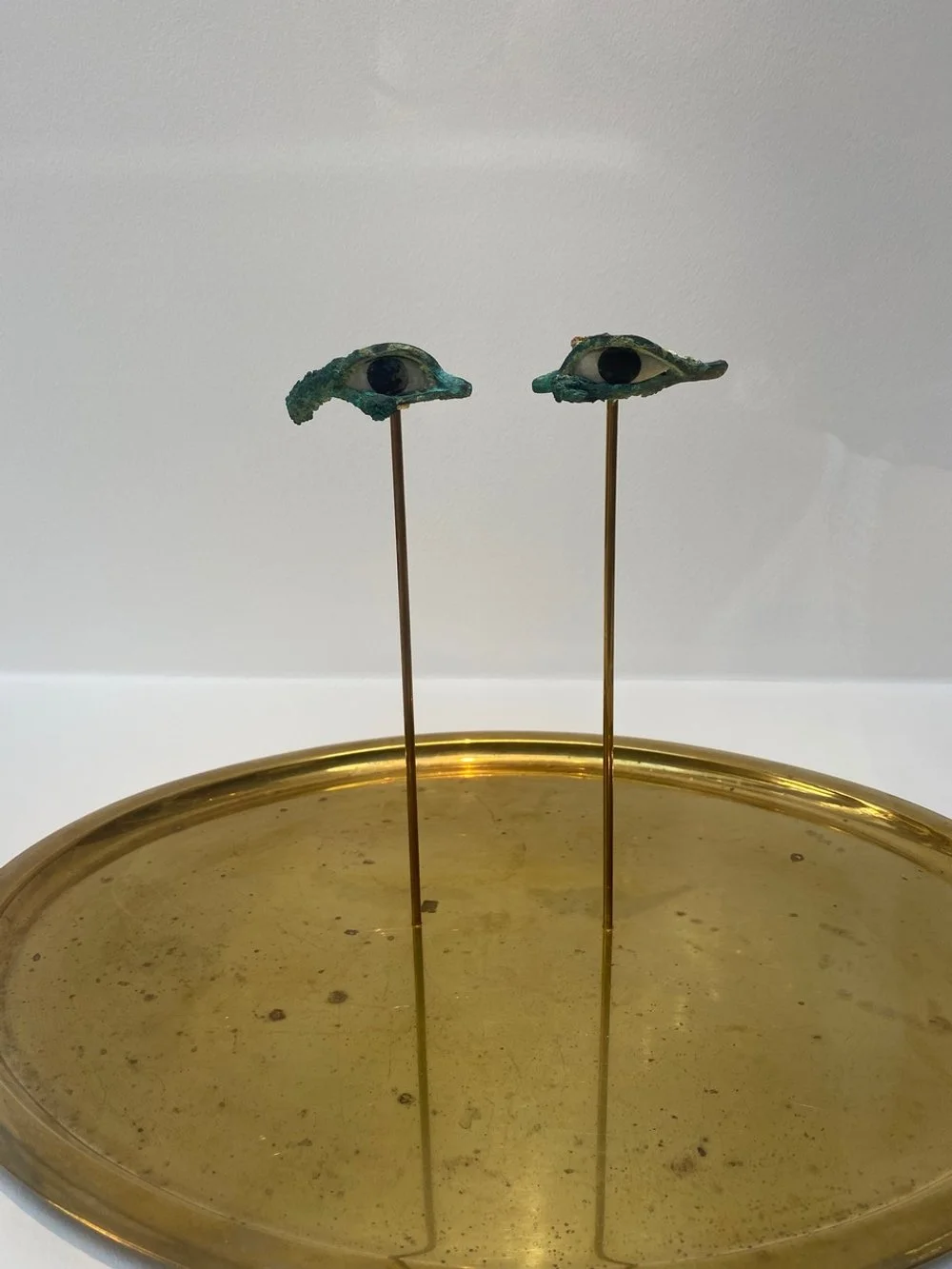

Figure 1. Your Gaze Scorches Me, from an Egyptian Sarcophagus, Ali Cherri, Vitrine, Bourse de Commerce

Figure 2. Noir Nana, Niki de Saint Phalle, Bourse de Commerce

I also went to see the David Hockney exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton one last time before it closes, today actually. This time, I wore the ‘End Bossiness Soon’ button that my friend Pieter sent me from Amsterdam. (Fig 3) While I was admiring one of my favorite paintings, Beuvron-en-Auge Village Square, (Fig 4) I started talking to a German couple who had just finished taking a selfie in front of the painting. I had to know why. Turns out, they are Hockey obsessives, too. They found out where David Hockney’s home in Normandy is by making friends with the owner of the pizzeria on the square of Beuvron. This while I enjoyed fine dining at the Michelin starred restaurant, also on the square. Whose chef admitted to knowing Hockney but who was too discrete to tell me more (unlike the guy at the pizzeria). The German couple showed me another selfie, also in front of the same painting. That time, taken where it normally lives, at the Wurth Museum in Germany. Also this week, I squeezed in time to see a fascinating exhibition about the artists Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean TInguely (Fig 5) and their patron, Pontus Hulten, at the recently restored Grand Palais. Which is gorgeous.

Figure 3. Me in front of David Hockney’s painting, both of us are wearing our End Bossiness Soon pin

Figure 4. Beuvron-en-Auge, Normandie, David Hockney

Figure 5. Cyclograveur, Jean Tinguely, 1960

This week’s subject is the fabulous exhibition I saw at the Institut du Monde Arabe - Le Mystère Cléopâtre (The Mystery of Cleopatra). The exhibition made me nostalgic for the years I homeschooled Nicolas. It seems like ages ago now, I guess because it was. One year he only wanted to read Homer’s Odyssey and learn about the Trojan War (I blame Brad Pitt). Then it was the Spartans. After that, the Pharaohs, especially Ramses II, who ruled for 68 years, had 200 wives and at least 156 children.

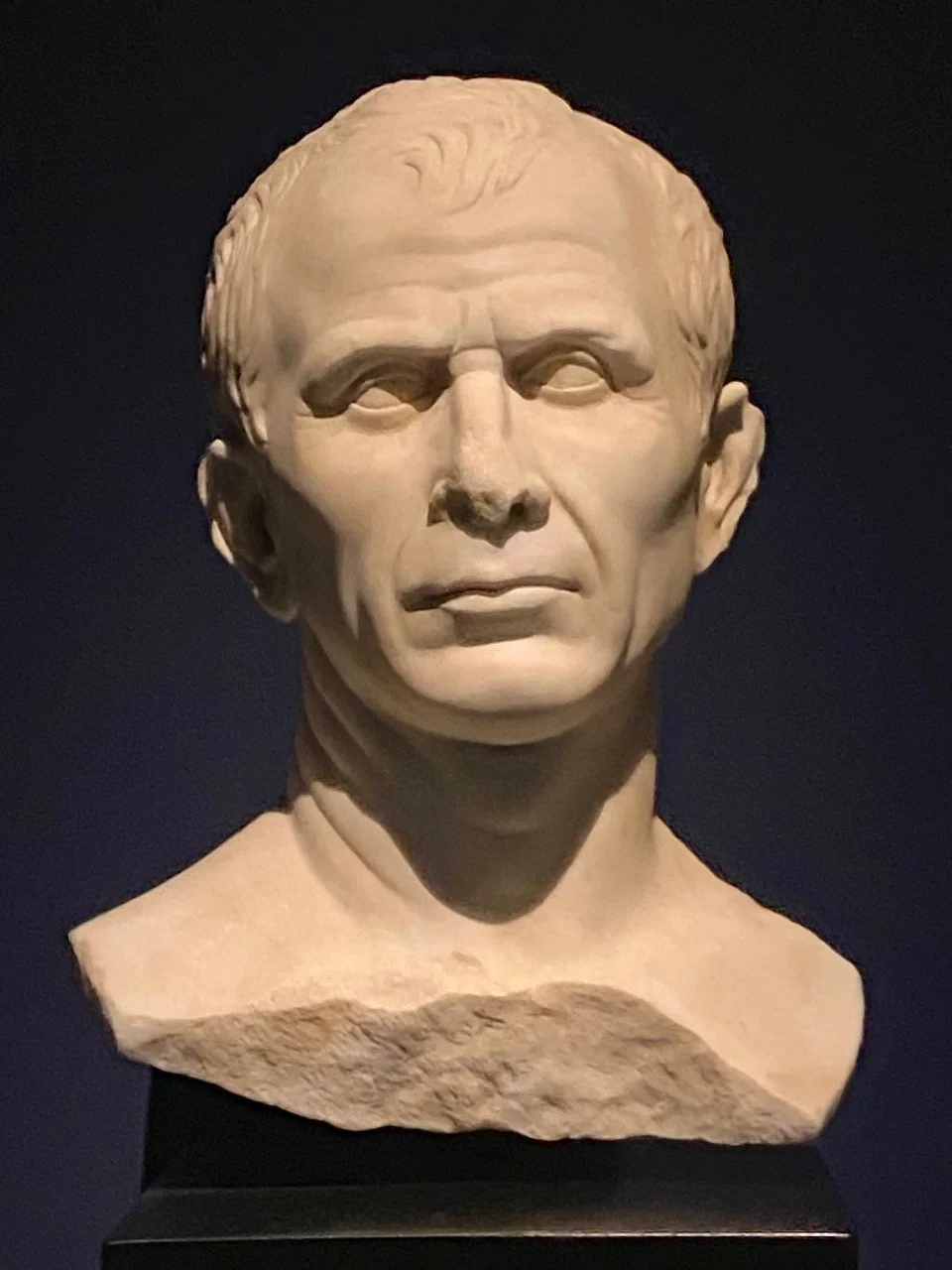

Finally I convinced Nicolas that if he wanted to learn about Julius Caesar, (which he did) we needed to know more about Cleopatra. We eventually got to Shakespeare and Liz Taylor, but we started with Stacy Schiff’s biography, Cleopatra: A Life. (Fig 6) With no ancient biography of Cleopatra as guide, Schiff relied upon the few historical sources that survive and the archaeological evidence available to tell the story of Cleopatra’s life and times. In Schiff’s book, Cleopatra is a fully developed person, a real person. We learn about her education, her role as a mother, her cultural interests and her religious beliefs. We learn about her relationships with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, (Figs 7, 8) and her relationships with her rivals and adversaries.(Fig 9) Cleopatra is shown as a politically savvy woman who focused on enriching her country and enhancing her subjects’ welfare.

Figure 6. Cleopatra A Life, Stacy Schiff

Figure 7. Julius Caesar, marble bust

Figure 8. Mark Antony, Marble bust

Figure 9. Octavian (also known as Augustus), Augustus of Prima Porta statue, Rome

The exhibition at the Institut du Monde Arabe begins with the Egypt of Alexander the Great’s successors, the family into which Cleopatra was born, the Ptolomies. Egypt was a country with great agriculture and mineral resources. Trade flourished - gold and ivory was imported from Africa, aromatics from Arabia, cinnamon and pearls from India. What the Egyptians didn’t keep, they exported to Greece and Rome. The Ptolemies ran the country like it was their personal property. They took a cut of every transaction - from taxes to tariffs. Pundits call Trump’s presidency a side gig to his main focus - getting richer. As I read about the Ptolemies, I realized they offered Trump a playbook to enrich his family at the expense of his country. Egyptians coexisted with Greeks and Jews; travelers and merchants, so Trump’s white supremacist stuff is obviously from a different playbook.

By the time Cleopatra came to power, Egypt was a Roman protectorate. Wanting to ‘Make Egypt Great Again,’ she chose allies and collaborators with one goal in mind - to restore her country to its former greatness. A shrewd political administrator, she rallied Egyptian and Greek priests to her cause, supporting temple construction and granting financial privileges. She issued a series of decrees protecting the peasants and punishing corrupt officials. She introduced a monetary reform. Definitely nothing Trump here.

As I read about Cleopatra’s shrewd diplomatic moves during a period of constant crisis in a world dominated by men, I understood why she bedded first Caesar and then Mark Antony. By giving birth to children fathered by these Roman rulers, the ties she forged between Egypt and Rome were not only military ones, they were blood ones. Something no male ruler could achieve.

Cleopatra was ruthless, she wasn’t into power sharing. She eliminated her competitors (her brother-husbands Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV) and then made Caesarion, (Fig 10) her son by Julius Caesar, an associate ruler. After Caesar’s assassination, she had three children with Mark Antony. In the end, aligning herself with Mark Antony was a mistake. She should have gone with Octavian who defeated them at the Battle of Actium (Fig 11). Antony committed suicide. Not wanting to be taken to Rome in chains, to be paraded and probably executed, Cleopatra committed suicide, too. Her death brought the Ptolemaic dynasty to an end.

Figure 10. Caesarion, Cleopatra’s son with Julius Caesar

Figure 11. Scene from Battle of Actium which Mark Antony and Cleopatra lost to Octavian

Cleopatra’s life was certainly interesting. But Cleopatra after Cleopatra is fascinating. She was and continues to be portrayed in various and conflicting ways. It just proves that the way history and historical figures are depicted tells us more about the writer and the artist and the times they lived in than about the subject and their time.

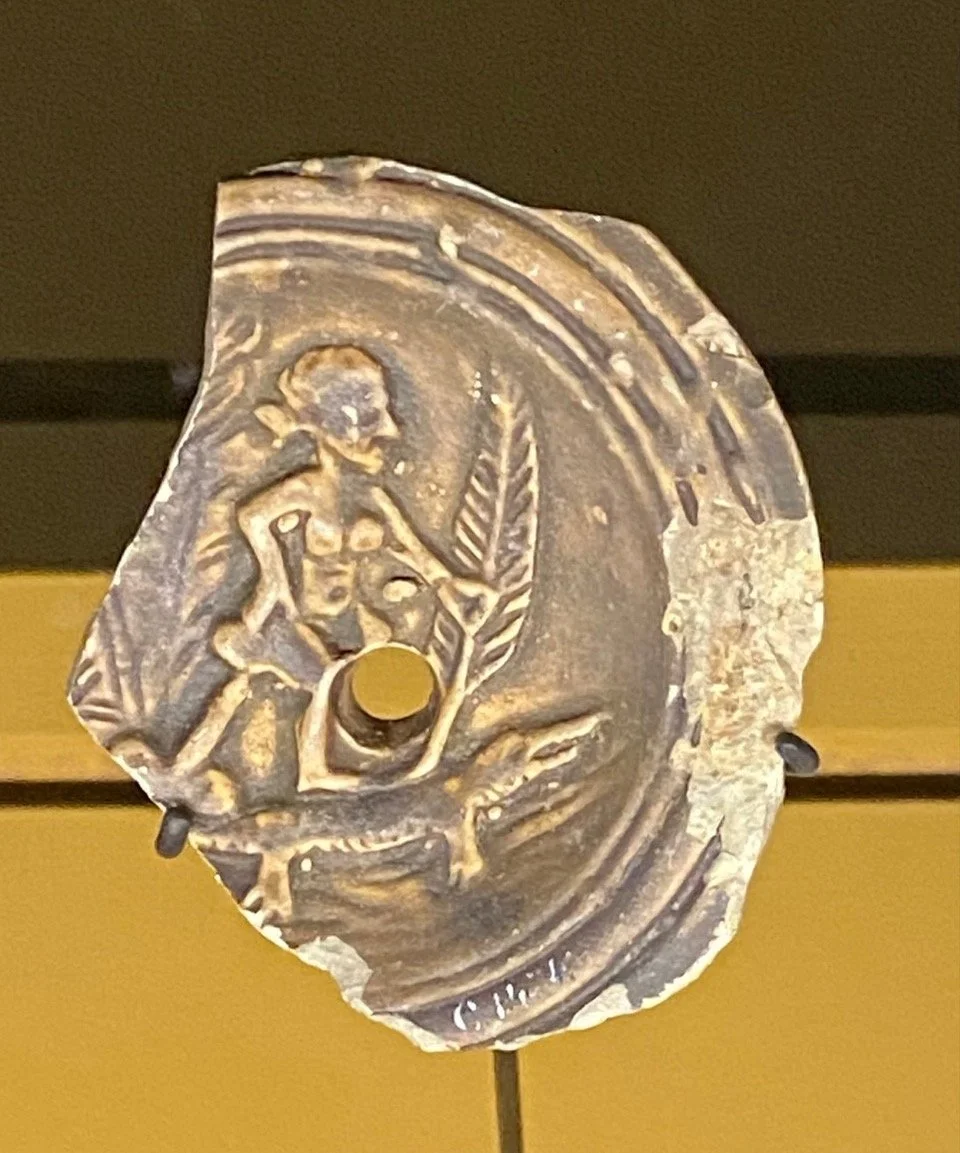

Authors close to Octavian, who after defeating Antony and Cleopatra, became Emperor Augustus, spread insults and slanders about Cleopatra. There is a fragment of an oil lamp that supposedly illustrates Cleopatra's sexual appetite. (Fig 12) It shows the naked queen, perched on a crocodile (symbol of Egypt) sodomized by a phallus. The aim was to discredit Cleopatra and present Caesarion, Octavian’s potential rival, not as Caesar's child, but as the son of an Oriental harlot who, among other things, was accused of having sex with her slaves (just like Thomas Jefferson). As I read about the ways in which the legitimacy of Cleopatra’s son was put into doubt, it reminded me of how Marie Antoinette was maligned and the legitimacy of her children questioned. (Fig 13)

Figure 12. Coin with naked Cleopatra standing on a crocodile being sodomized by a phallus

Figure 13. Marie Antoinette and Lafayette, one of many scurrilous cartoons and caricatures about this queen

Virgil denounced Cleopatra, saying that she cast a spell on Mark Antony. Horace described her as "a fatal monster" and a "demented queen.” Propertius called her a whore, the antithesis of Roman virtue. To Plutarch and Suetonius, Cleopatra was manipulative, lustful and alien. By discrediting her they legitimized Rome’s superiority.

Ancient history, written by men, downplayed Cleopatra’s role as head of state in favor of a distorted, hyper-sexualized and manipulative image. And yet Cleopatra’s fame continues to grow while many of the men who disparaged her have been forgotten.

Egyptian authors, on the other hand, celebrated Cleopatra. The historian Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam (803-871) called Cleopatra an ideal mother who cared for the well-being of her subjects. Saying nothing about Cleopatra's physical charms, he celebrated her erudition and knowledge. Around 1200, the writer Murtada ibn al-Khafif commended Cleopatra for her bravery, her preference for suicide rather than becoming the wife of a foreign conqueror. The poet Al-Masudi depicted Cleopatra as a philosophical woman who enjoyed the company of scholars and physicians. He admired her scientific knowledge. He didn’t mention her looks.

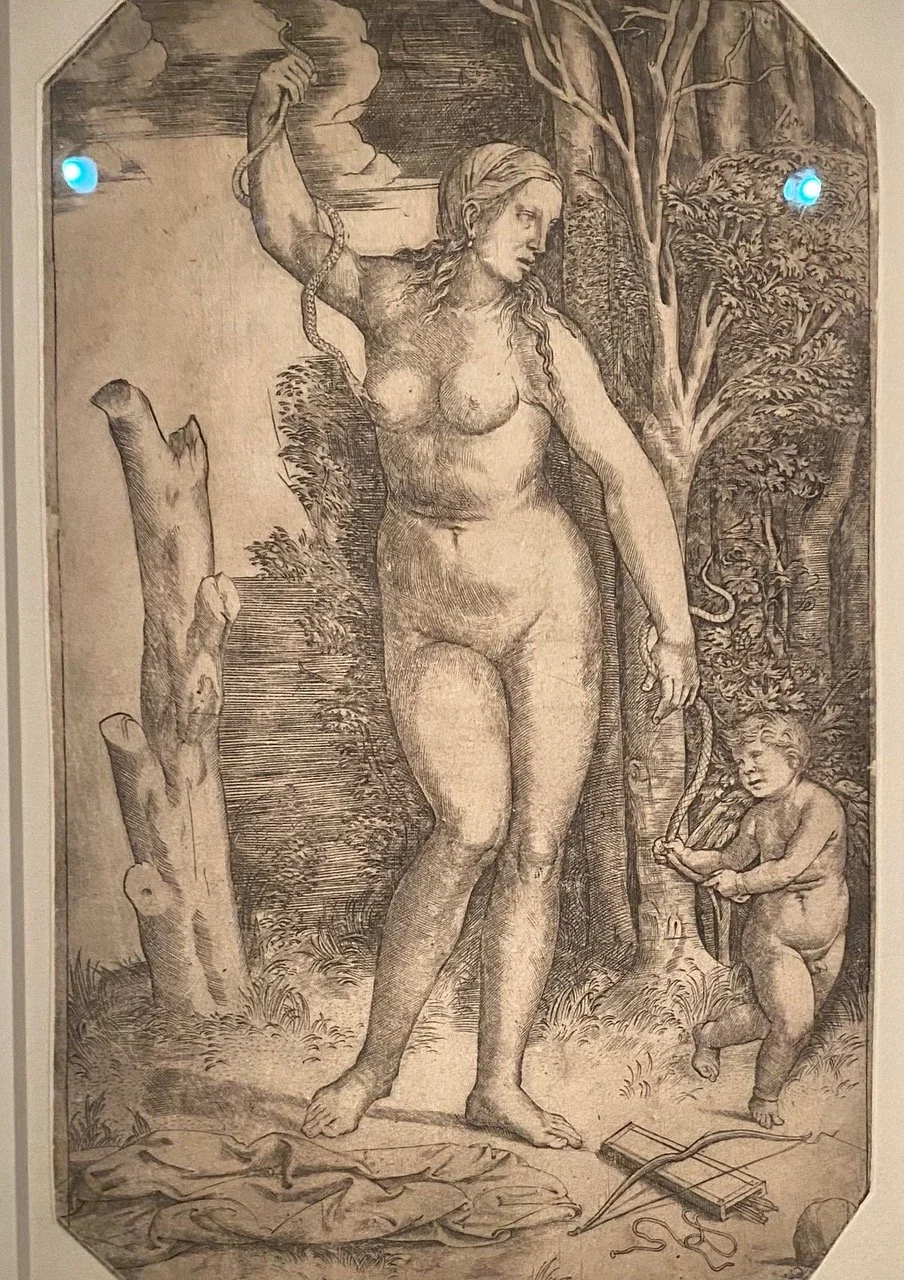

In Western art, Cleopatra has sometimes been depicted as Eve, the temptress (Fig 14). Lavinia Fontana, a 16th-century female artist portrayed Cleopatra as a knight. (Fig 15) Other artists, chief among them, Tiepolo, celebrated her fantastic wealth by depicting the banquet she held for Mark Antony during which she dropped a huge pearl into a goblet of wine where it would disintegrate. (Fig 16) Mostly she was depicted at the moment of her death. It’s a subject that allowed male artists to show a nude or semi-nude female in a languorous pose. (Figs 17-20) As the curators tell us, Cleopatra “became burdened with the misogynistic narrative of patriarchal cultures, with her death as the moral conclusion… Cleopatra enjoyed dying.”

Figure 14. Cleopatra with serpent with Eve and Venus (Cupid) references, Giacomo Francia, 1550

Figure 15. Cleopatra as a Knight, Lavinia Fontana, 1585

Figure 16. Banquet of Cleopatra, GB Tiepolo (study for painting at Musee Cocgnac-Jay, Paris)

Figure 17. Cleopatra, Roman statue

Figure 18. Cleopatra Dying, Francois Barois, 1700

Figure 19. Cleopatra Dying, Antoine Rivalz, 1700

Figure 20. The Death of Cleopatra, Jean-Andre Rixens, 1874

As the curators note, following Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt (1798-1801), “taste was shaped more by popular Egyptomania than by scholarly Egyptology. In paintings at the Salon, the exotic prevailed. Orientalism revived propaganda against the "foreigner". The West was civilized and rational, the East was barbaric and sensual. Cleopatra was fabulous and mysterious but she was also and mainly despotic and decadent. (Fig 21)

Figure 21. Cleopatra watching condemned men die of poison, Alexandre Cabanal, 1883

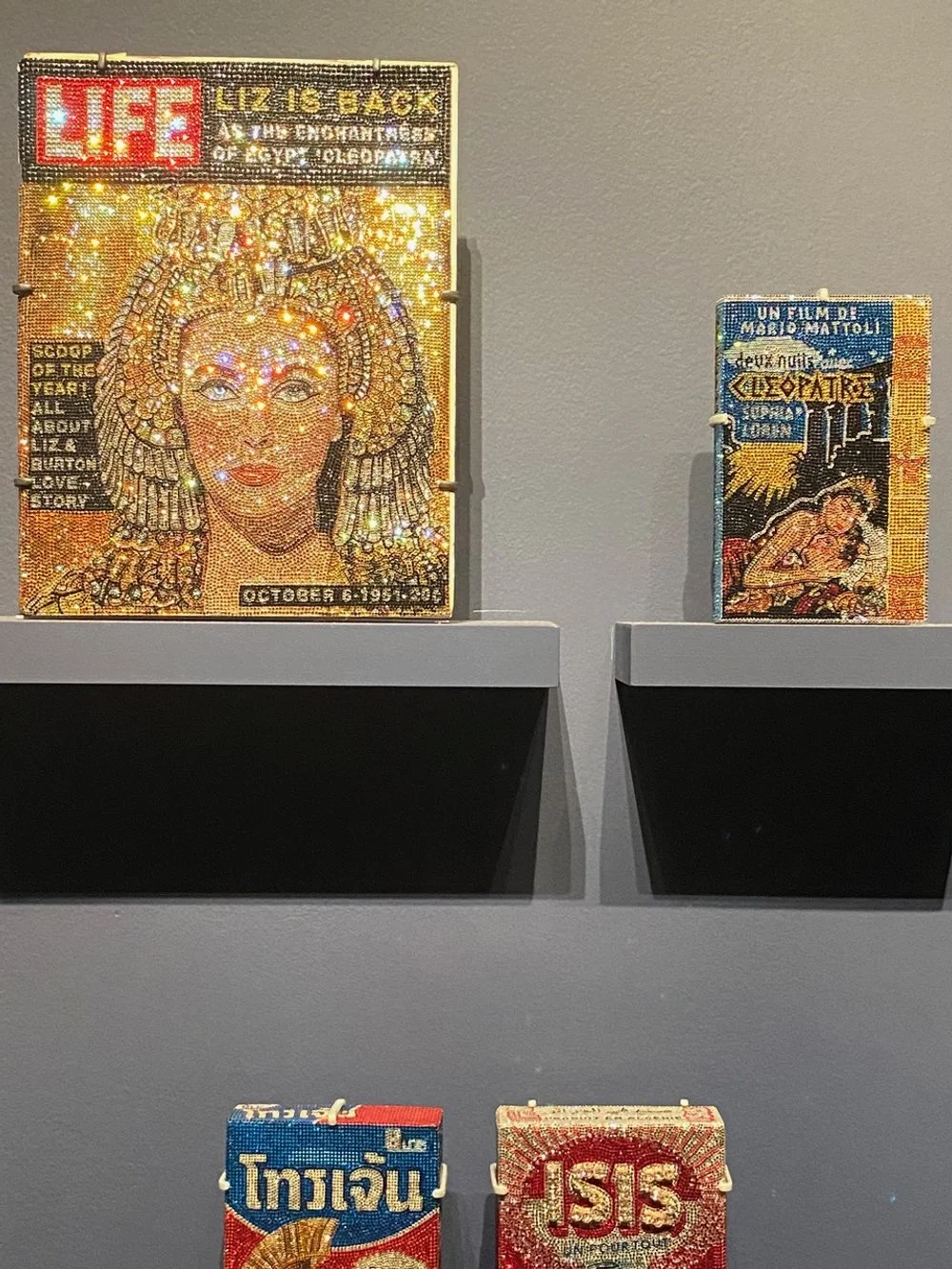

In 1899, a 54 year old Sarah Bernhardt played the role of Cleopatra (Fig 22) in Shakespeare’s tragedy Antony and Cleopatra (Cleopatra died at age 39). On the movie screen, Cleopatra was portrayed by Claudette Colbert (1934), Vivian Leigh (1945) and Sophia Loren (1953) before a 30 year old Liz Taylor played her in 1963. (Fig 23) That film was called simply, Cleopatra. Liz took one lover, Caesar (played by Rex Harrison) and then another, Mark Antony (played by her real life lover, Richard Burton).

Figure 22. Sarah Bernhardt as Cleopatra, Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse, after 1890

Figure 23. Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra, 1963

At the same time that her popular and glamorous screen image was developing, a different identity for Cleopatra was emerging in both Egypt and the United States. In Egypt, Cleopatra became a nationalist symbol of resistance to British imperialism (1882-1956). During the civil war in the United States, Cleopatra became a source of pride for African-American women. The first internationally renowned female African-American artist Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907) took Cleopatra as her subject. (Fig 24) To African slaves, Cleopatra’s suicide was seen as an act of bravery and resistance by a leader who preferred death to submission, freedom to slavery. I couldn’t help but think about Toni Morrison's novel Beloved, based upon a true story of a former slave who had escaped to freedom but who was afraid that she would be recaptured. In fear and desperation, she killed her infant daughter to spare her a future of enslavement.

Figure 24. The Death of Cleopatra, Edmonia Lewis, 1876

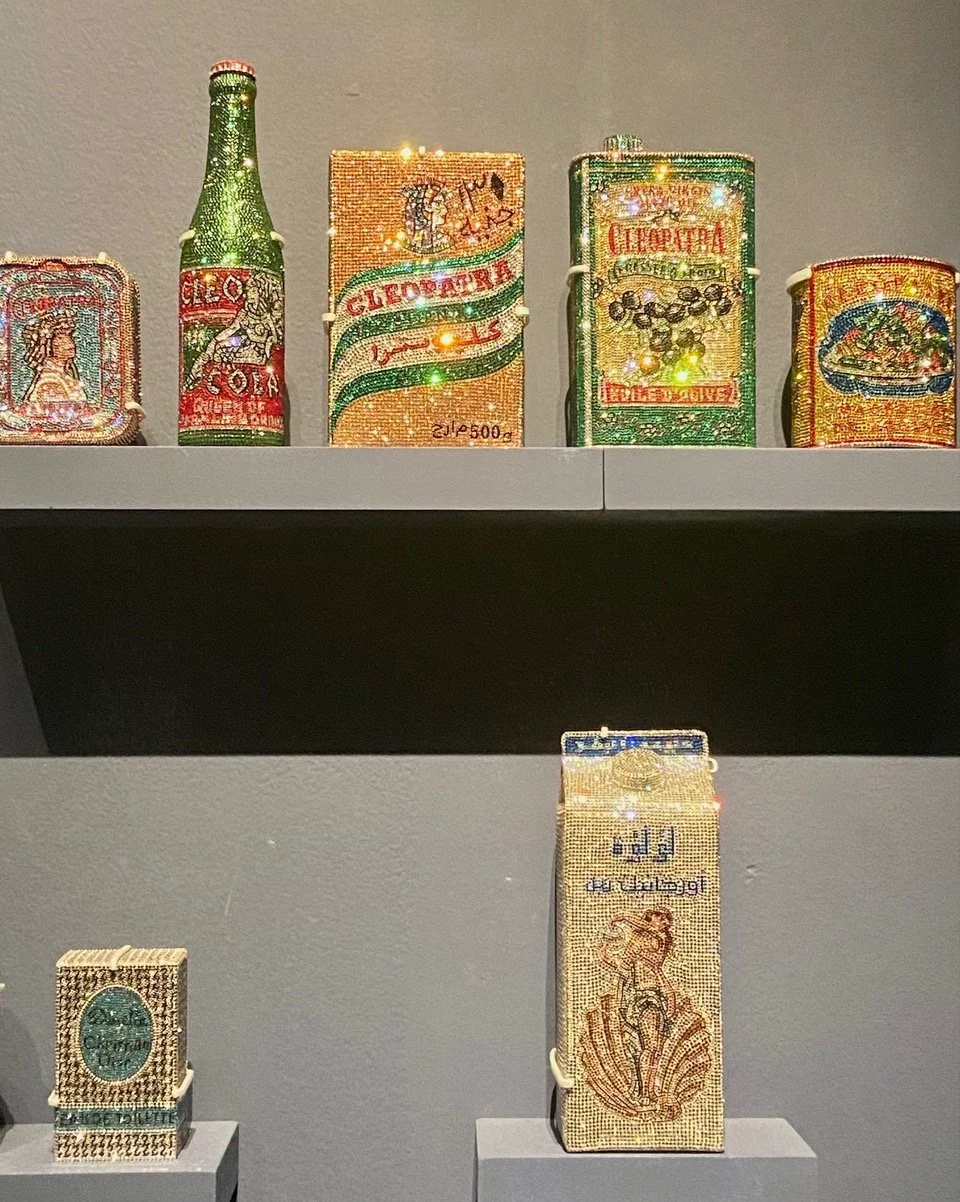

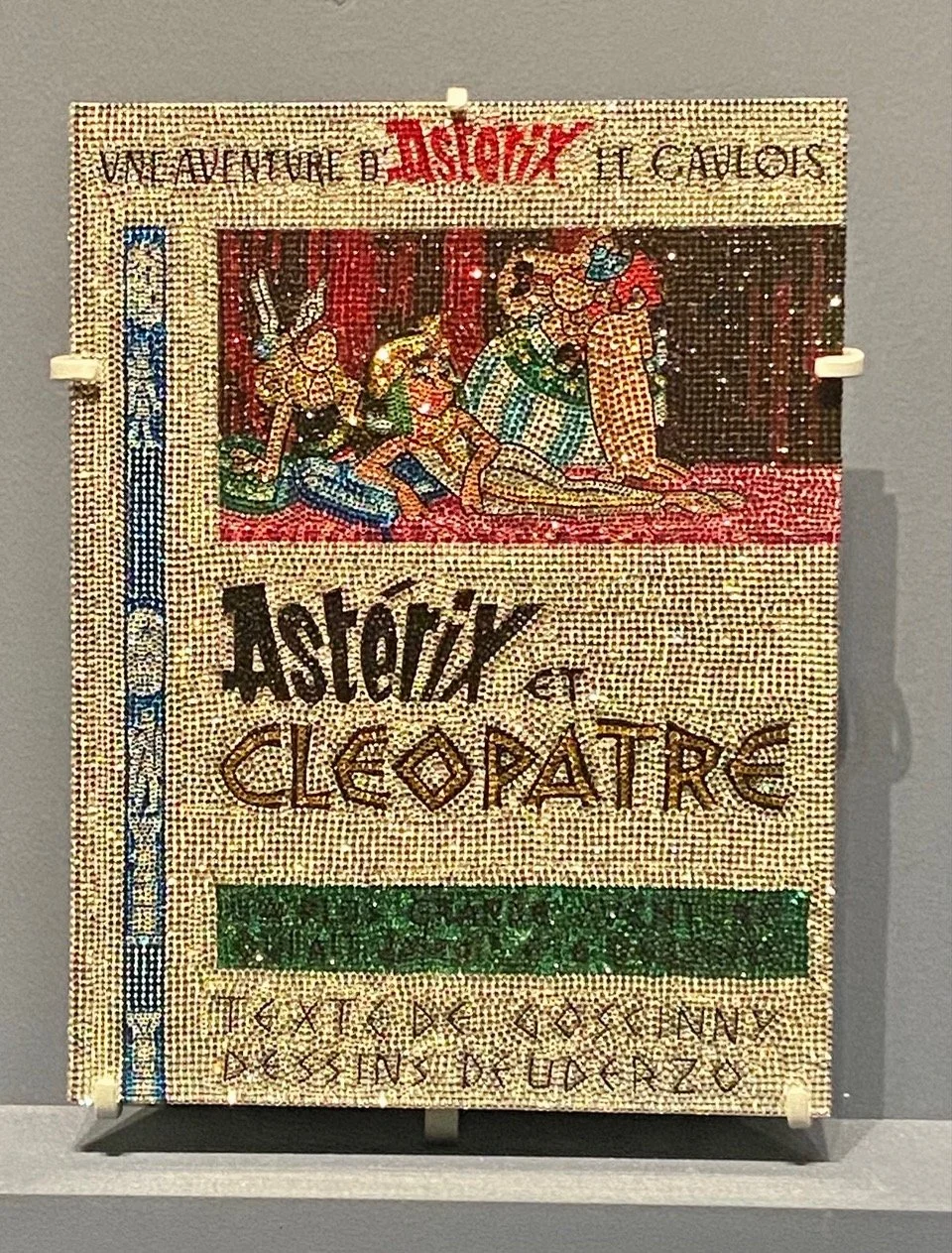

One of the most fascinating aspects of this exhibition was the curators’ decision to bring depictions of and references to Cleopatra right up to the present day. They write that “with the proliferation of images, the glamorization of the star system, the massification of culture” Cleopatra has become a consumer object, welcomed into every home - “a beauty queen, fashion muse and advertising brand..... (with which) all social classes could identify….”

Shourouk Rhaiem's piece is one example. "I became involved with The Mystery of Cleopatra when the curator visited my studio and noticed a packet of Cleopatra soap – a brand I grew up with… As soon as she saw it, she told me she was preparing an exhibition on Cleopatra and invited me to be part of the project.” Her installation, Cleopatra's Kiosk, (Figs 25-27) is filled with everyday products with Cleopatra's image on them. Items like soap, olive oil, sardines and rice. “I sourced these items from around the world. It became a kind of global treasure hunt" Rhaiem calls her process "pop archaeology.” After she unearths forgotten relics of consumerism and finds ones still on store shelves, she transforms them into precious artifacts by covering them with Swarovski crystals! Rhaiem finds Cleopatra's boldness and opulence inspiring. "She was a Middle Eastern queen covered in gold, pearls and jewels, unafraid to display her wealth, her power and her status.” As the artist notes, Cleopatra is the most famous woman in the world, which we can confirm because her visage continues to sell products.

Figure 25. Cleopatra's Kiosk, Shourouk Rhaiem, 2025

Figure 26. Cleopatra’s Kiosk, Shourouk Rhaiem, 2025

Figure 27. Cleopatra’s Kiosk, Shourouk Rhaiem, 2025

Another artist, Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos, went back to the ancient texts that disparaged Cleopatra's political and intellectual abilities and focused instead on her physical attributes. Taking excerpts from ancient authors who defamed Cleopatra, Kosmatopoulos edited and corrected their texts with her own words, thereby questioning the making of history. Who writes it? And why? And for whom? (Fig 28)

Figure 28. Corrected texts about Cleopatra, Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos, 2019

Cindy Sherman’s self portrait is a melange of dangerous women - Medusa, Venus and Cleopatra. (Fig 29) Harking back to Orientalism, she lies upon a sofa, languid, lascivious (and maybe pregnant?). But also confrontational. Her frontal pose and insistent gaze take her from object to subject. She simultaneous provokes the male gaze and dares voyeurism.

Figure 29. Cleopatra (and Medusa and Venus) Cindy Sherman

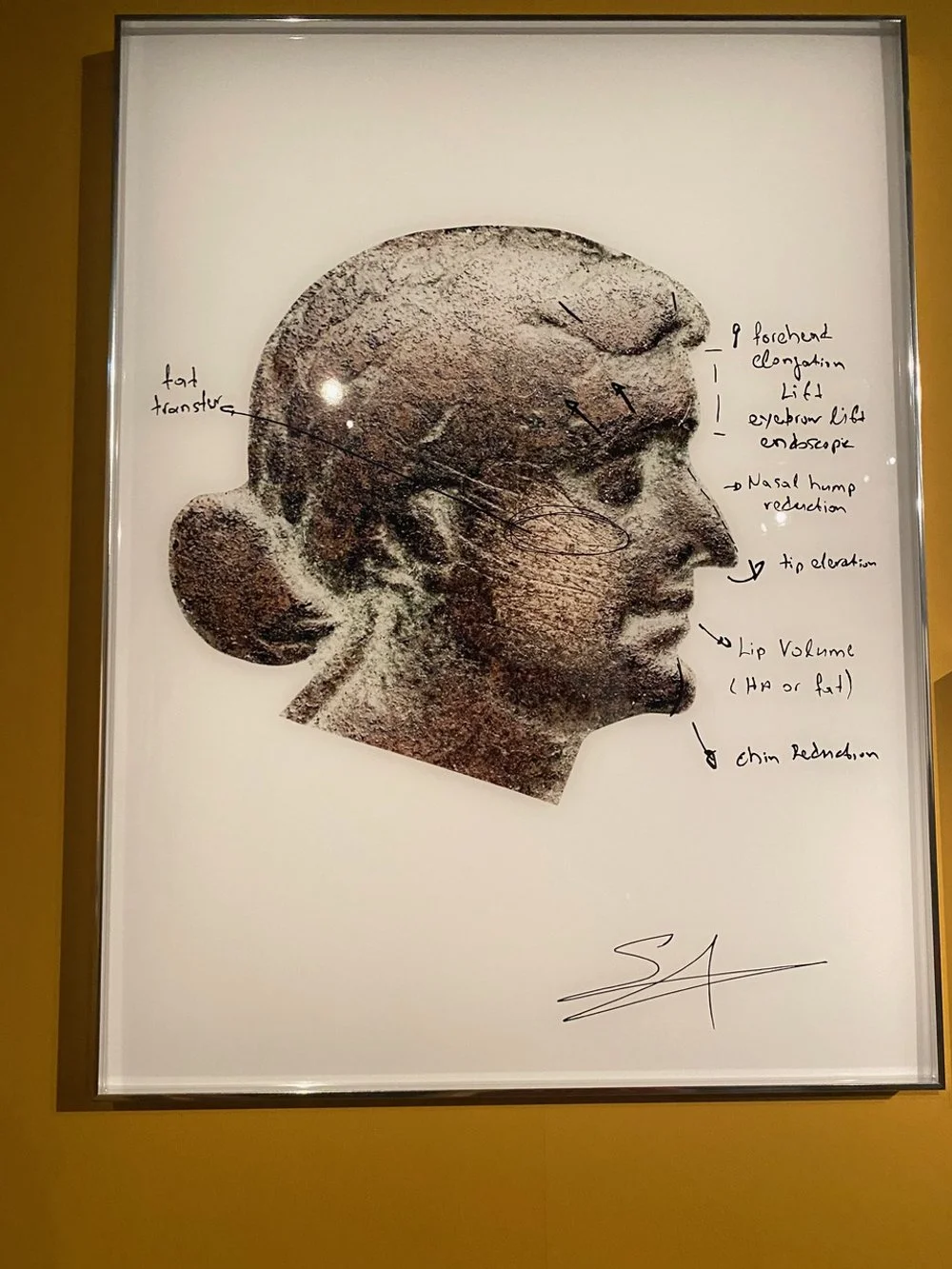

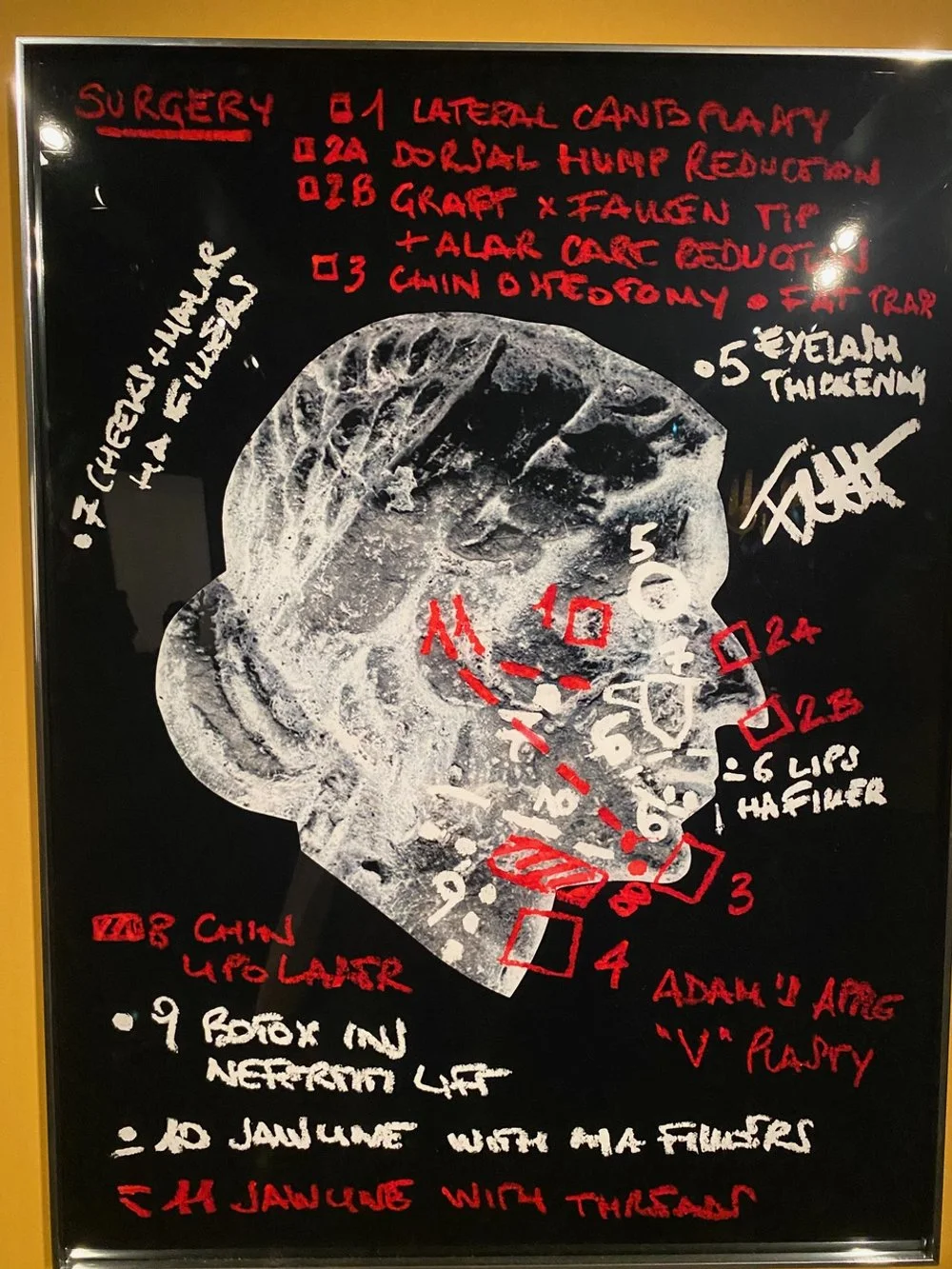

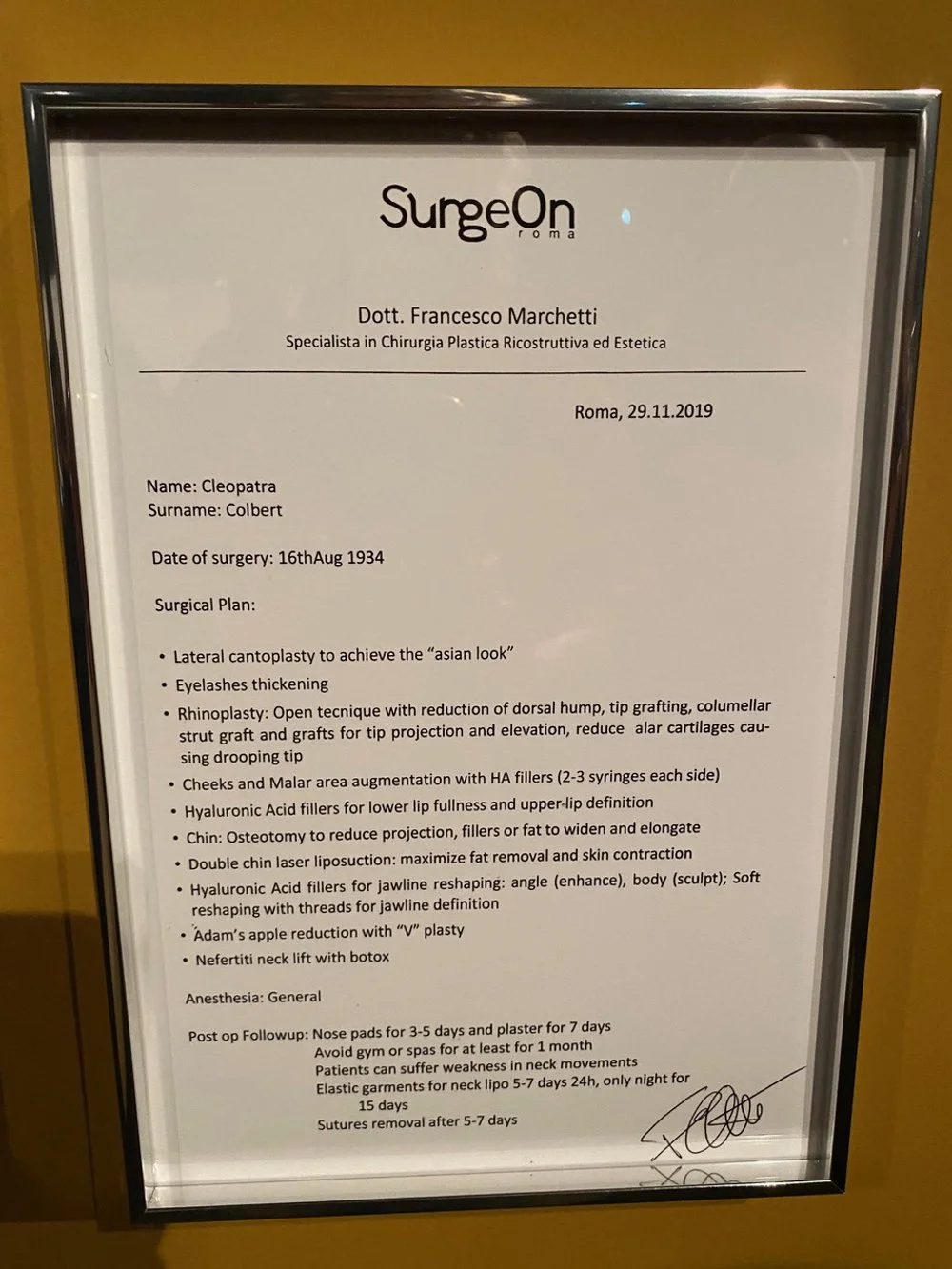

In another work by Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos called, ‘I want to look like Cleopatra as Vivien Leigh,’ the artist sent a copy of Cleopatra's portrait on ancient coins to three plastic surgeons, an Italian, a Greek and an Egyptian. She asked them what procedures Cleopatra would have to undergo to bring her profile into line with the canons of 20th century beauty. The corrections that would make Cleopatra conform to the looks of the actresses who portrayed her. (Figs 30 - 33) This interactive piece, calling upon professionals in other fields to voice their opinions and become part of the project, reminded me of Sophie Calle’s piece from 2007, for the Venice Biennale. It’s the interpretations she received from 107 experts (women) from a variety of fields, when she asked them to comment on the break-up letter she received from her boyfriend. (34)

Figure 30. Cleopatra coin, Egypt during reign of Cleopatra

Figure 31. 'I want to look like Cleopatra as Vivien Leigh’ Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos, 2019

Figure 32. 'I want to look like Cleopatra as Vivien Leigh’ Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos, 2019

Figure 33. 'I want to look like Cleopatra as Vivien Leigh’ Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos, 2019

Figure 34. Take Care of Yourself, Sophie Calle, 2007

The exhibition concludes with Barbara Chase-Riboud’s 1973 Cleopatra’s Chair, a massive bronze throne made up of thousands of tesserae. It is both gleaming and fragile, monumental and abstract. And empty. “She doesn’t give us Cleopatra’s likeness. She gives us the throne, and leaves it unoccupied.” (Fig 35)

Figure 35. Cleopatra’s Chair, Barbara Chase-Ribaud, 1994

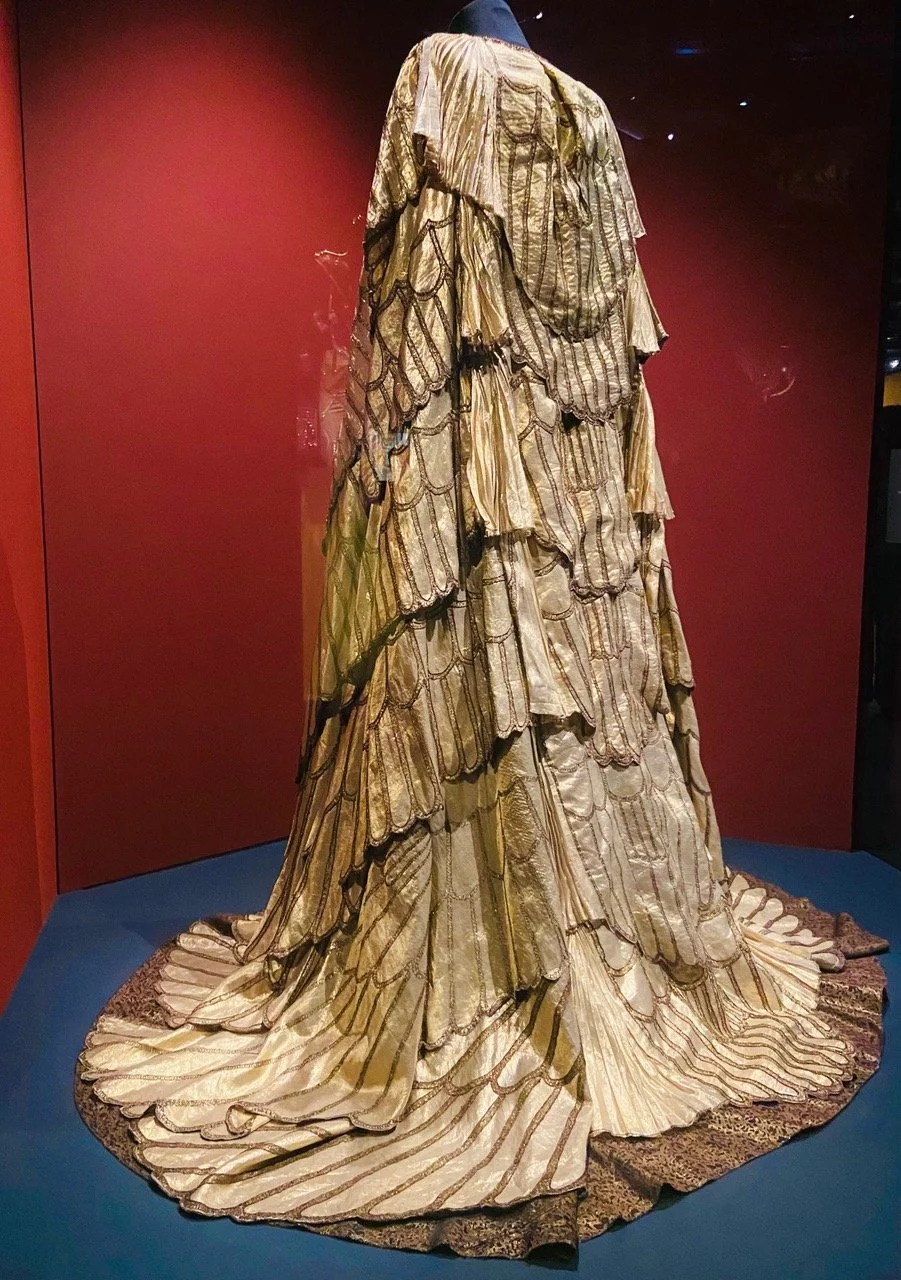

This exhibition begins with the real Cleopatra and then traces how Cleopatra went from an historical figure to a legend; from a legend to a myth and from a myth to an icon. As an icon, she combines “passion and death, voluptuousness and cruelty, wealth and war, politics and feminism.” Her presence sheds a light on the various and contradicting attitudes and impressions the West has both of Pharaonic civilizations and of women in power (Figs 36-38). Gros bisous, Dr B.

Figure 36. Cleopatra Dress, John Galliano for Dior, 2004

Figure 37. John Galliano for Christian Dior, Headdress detai

Figure 38. Robe Elizabeth Taylor wore in 1963 Film, Cleopatra

Thanks to those of you who sent Comments about last week’s post on the photographer, Robert Doisneau, they were much appreciated.

New comments on I don't photograph life as it is, but life as I would like it to be:

Wonderful review. Sorry to miss this exhibition, Kathleen

The article was just what we needed. Joyful and fun. It’s really getting scary over here. Went to the ball game yesterday. Was looking for more illicit Jumbotron sittings. Our home team lost. They are not doing well this season 😫. I hope your son enjoys his new venture. It seems very brave to me but a wonderful experience too. Deedee, Baltimore