I don't photograph life as it is, but life as I would like it to be

Robert Doisneau Instants Donnés, Musée Maillol

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musing, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. Finally, I am living alone in my little Parisian apartment. Three months after an anticipated 3 week visit, Nicolas has flown to China to begin his new life. With work visa in hand, he’ll put Graffiti and Glass Blowing aside, and learn how to teach English as a foreign language while teaching English as a foreign language.

Here’s a tidbit I forgot to mention last week in my review of Maya Arad’s Happy New Years. In Leah’s last letter, written in September 2016, she anticipates the election of the first woman president of the United States. Nine years later, we’re still waiting for that to happen. With museums and cultural institutions being told to avoid mentioning the negative aspects of slavery. There were positive aspects? As maybe Churchill said, “history is written by the victors.” And here we are, not knowing what to do as 60 years of trying to right the wrongs of past victors is being undone. Happily, today’s subject is the opposite of all that awfulness.

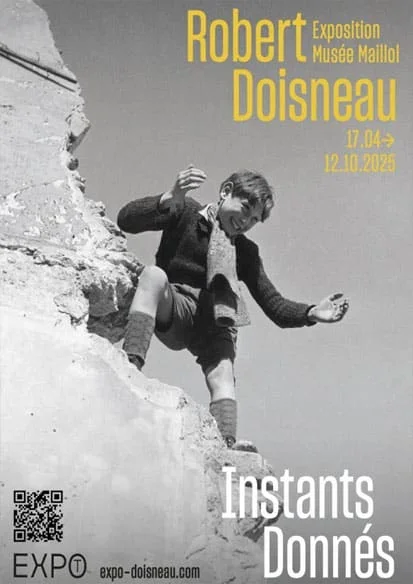

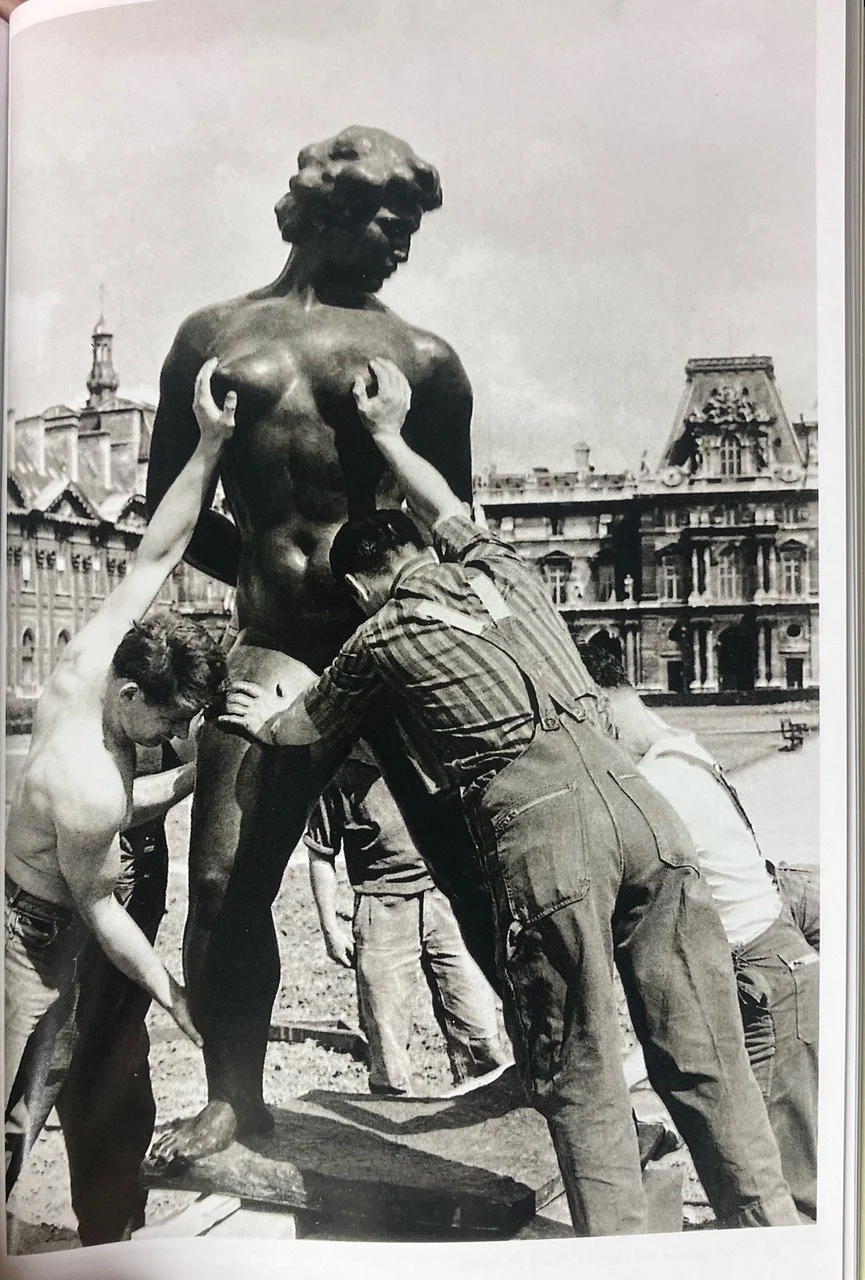

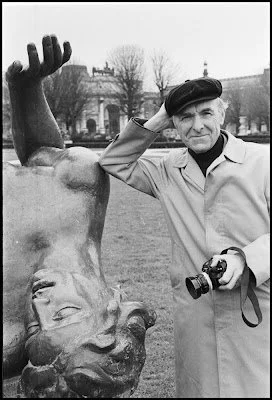

This week we’re at the Musée Maillol to see the joyful and thoughtful exhibition on the photographs of Robert Doisneau. It’s on until October 12, so if you’re in Paris this fall, you should definitely try to see it - and see a few Maillol sculptures, too …. (Figs 1, 2)

Figure 1. Maillol Statues being moved in Jardin du Luxembourg

Figure 2. Maillol Statue & Robert Doisneau at Jardin du Luxembourg

Robert Doisneau was born in 1912. His father, a soldier, died in battle when Robert was 4. Three years later, his mother died. At 13, he enrolled in a craft school where he learned engraving and lithography and took classes in figure drawing and still life. A few years later, he found photography. He was so shy that his first pictures were of cobblestones. Only gradually did children and then adults become his subjects.

In 1934, Doisneau began working as an industrial advertising photographer for the Renault car factory outside of Paris. After 5 years, he was fired. Why? Because he could never get to work on time! Which, for a factory full of employees clocking in, must have been more than a little aggravating for management.

As the curators of this exhibition explain, it was at the Renault factory that Doisneau’s political awareness was born. It was here that his solidarity with the working class emerged. He chronicled the lives of those left behind, from the miners of Lens to the prostitutes of Paris; from the men abandoned in the prison-hospice of Nanterre in the 1950s to the steelworkers of the Fensch Valley in the 1970s. These photographs were mostly commissions he received from the left-wing press - Regards, Action, La Vie ouvrière. He gave those assignments priority over his other work. Those photos may not be as well known as his delightfully humorous images, but they are as essential a part of his photographic legacy. (Figs 3, 4)

Figure 3. Miner in Lens, 1945

Figure 4. Prison-hospice of Nanterre

During the war (1940 - 1945), using his training as an engraver and lithographer, Doisneau made passports, identity cards and Ausweise (visas used to cross from Nazi-occupied territory into the Free Zone), to help out his friends and those, in Doisneau’s words, “in the shit.” An exhibition a couple years ago focused on Doisneau’s work for the Resistance. (Fig 5) Here’s one story from that exhibition. One night, a Polish immigrant, Serge Dobkowski, knocked on Doisneau’s door. He was being followed by the Nazis and he desperately needed fake papers to escape occupied France. He’d heard that Doisneau was the man for the job. Usually it took Doisneau 48 hours to make a false identity card. But this time there wasn’t enough time. So Doisneau took and printed Dobkowski’s photo and glued it to his own identity card. Dobko, who became a lifelong friend, was able to flee France and spend the rest of the war as Robert Doisneau.

Figure 5. Robert Doisneau, L’esprit de Résistance. Photo by Doisneau of Resistance literature being distributed

The exhibition catalogue ruefully noted that by 1940, Doisneau was no stranger to forgery, having doctored his time card so many times when he worked for Renault! Needless to say, the stakes were much higher during the war. If he had been discovered, he could have been deported or even executed. “He hid his work in progress in the roller blinds in the glass roof of his studio and destroyed his negatives and prints once the work was done. His flat was searched for compromising photos three times during the war.”

As the tide turned, as “resistance fighters rose up to battle the occupying Germans,” he openly photographed them tearing up paving stones, lifting asphalt, moving vehicles, collecting sandbags, building barricades. (Fig 6) When people began lauding him as a member of the French Resistance, he was, according to his daughter, “absolutely furious at being ranked alongside people who had risked their life for the Resistance.” But he had.

Figure 6. Sandbag barricades during the Resistance

After the war, he returned to freelancing and sold photographs to international magazines like Life. Vogue Magazine hired him in 1949 as a fashion photographer. The editors hoped that he would bring a fresh perspective to what was happening in French society after the war. So he photographed social events and grand balls and occasionally beautiful women in elegant surroundings. Vogue gave him access to a world that was not his own, but a world whose beauty and sophisticated grace he was able to appreciate, for a few years anyhow. (Figs 7, 8)

Figure 7. Vogue Magazine Cover

Figure 8. Brigette Bardot for Vogue, 1950 for Vogue Magazine

The 1950s was Doisneau's decade, when people most appreciated his kind of photographs. He took his most recognizable photo in 1950, ’Kiss by the Hotel de Ville.’ (Fig 9) It was taken on assignment for Life Magazine as part of a photo-essay on couples kissing in Paris. It became an internationally recognized symbol of young love in Paris. It was mostly forgotten for the next 30 years and then, in the 1980s, it resurfaced and began appearing on posters and postcards. This renewed interest had a downside for Doisneau. The names of the young man and woman kissing had remained a mystery. It wasn’t until 1992 (2 years before his death) that Doisneau had to share the identity of the couple and that was only because another couple, thinking that they were the couple Doisneau photographed, sued him for "taking their picture without their knowledge".

Figure 9. Kiss by the Hotel de Ville, 1950 for Look Magazine

Turns out, this second couple had met with Doisneau and his older daughter in the 1980s to tell Doisneau that they thought they were the couple in the photograph. He didn’t refute their claim even though he knew it wasn’t true. Why? Because, he explained to his daughter, he "did not want to shatter their dream.” But it wasn’t a dream, it was greed. They took him to court for compensation because under French law an individual owns the rights to their own likeness. In court, Doisneau was obliged to reveal not only the true identity of the kissing couple but to admit that the photo had been posed. Yes posed but only after he had seen the two lovers kiss and asked if they would repeat their kiss for him to photograph. In his court testimony he said, "I would never have dared to photograph people like that. Lovers kissing in the street? Those couples are rarely legitimate.” His comment made me think of the couple caught on the Jumbotron ‘Kiss-Cam’ at the Coldplay concert a few weeks ago who were indeed, ‘not legitimate’. (Fig 10)

Figure 10. Jumbotron ‘Kiss-Cam’ at Coldplay Concert

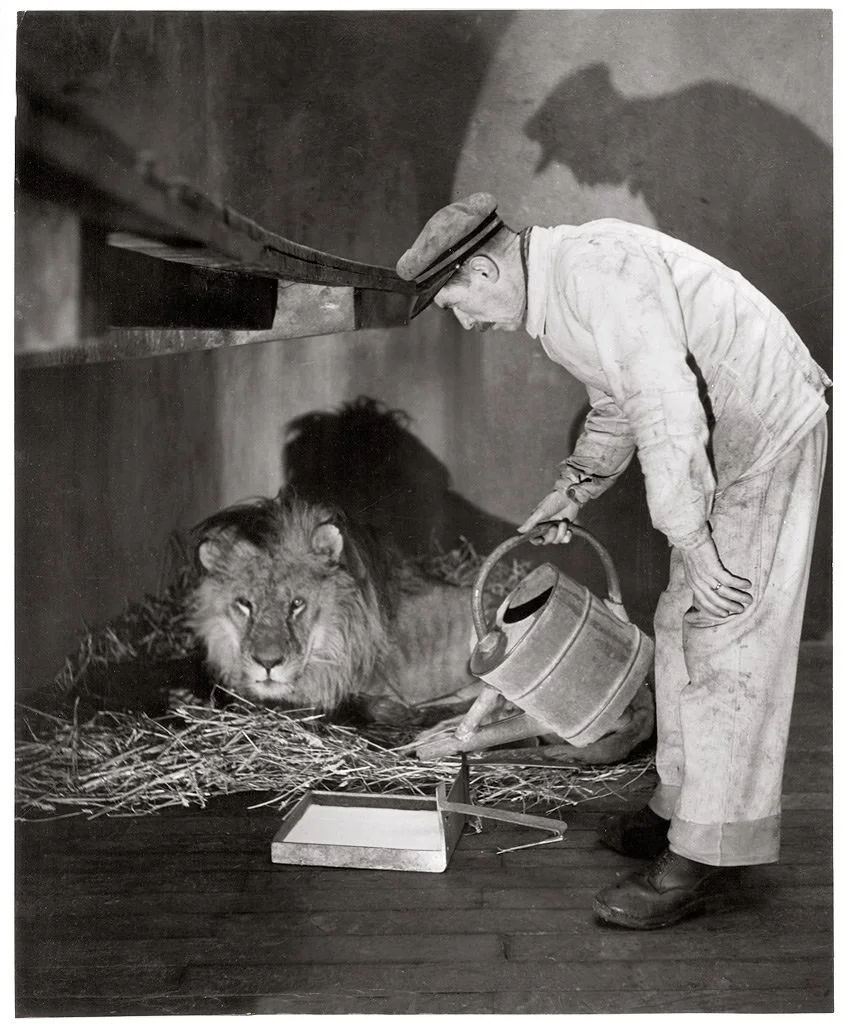

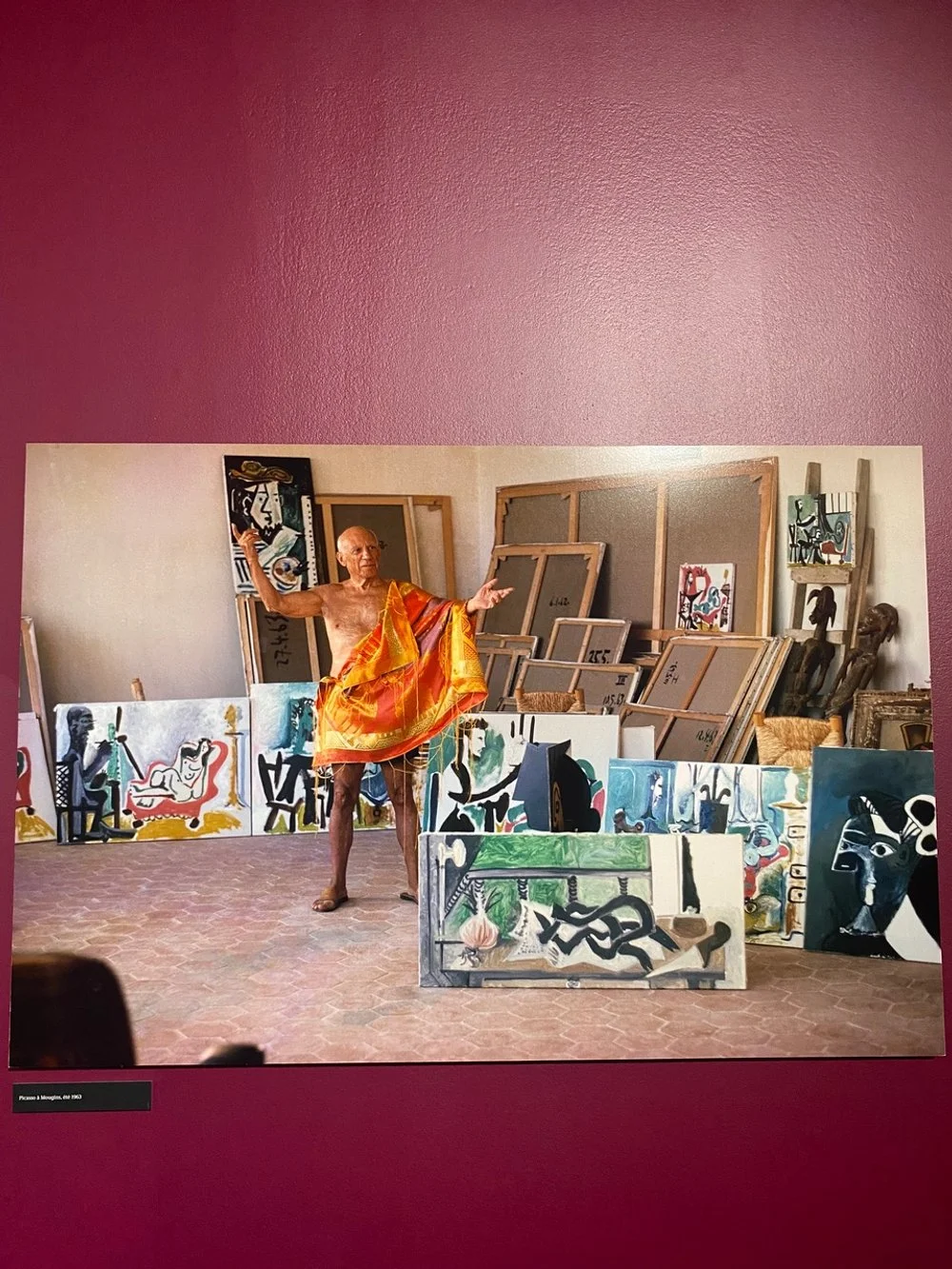

The curators contend that Doisneau’s is “the story of a modest life, made fascinating by the camera he never left behind. “Tell me, (he once said) what other profession would have allowed me to enter the lion's cage at Vincennes Zoo and Picasso's studio?” (Figs 11, 12)

Figure 11. Lion’s den at the Vincennes Zoo, 1943

Figure 12. Les pains de Picasso (Picasso with bread fingers), 1950

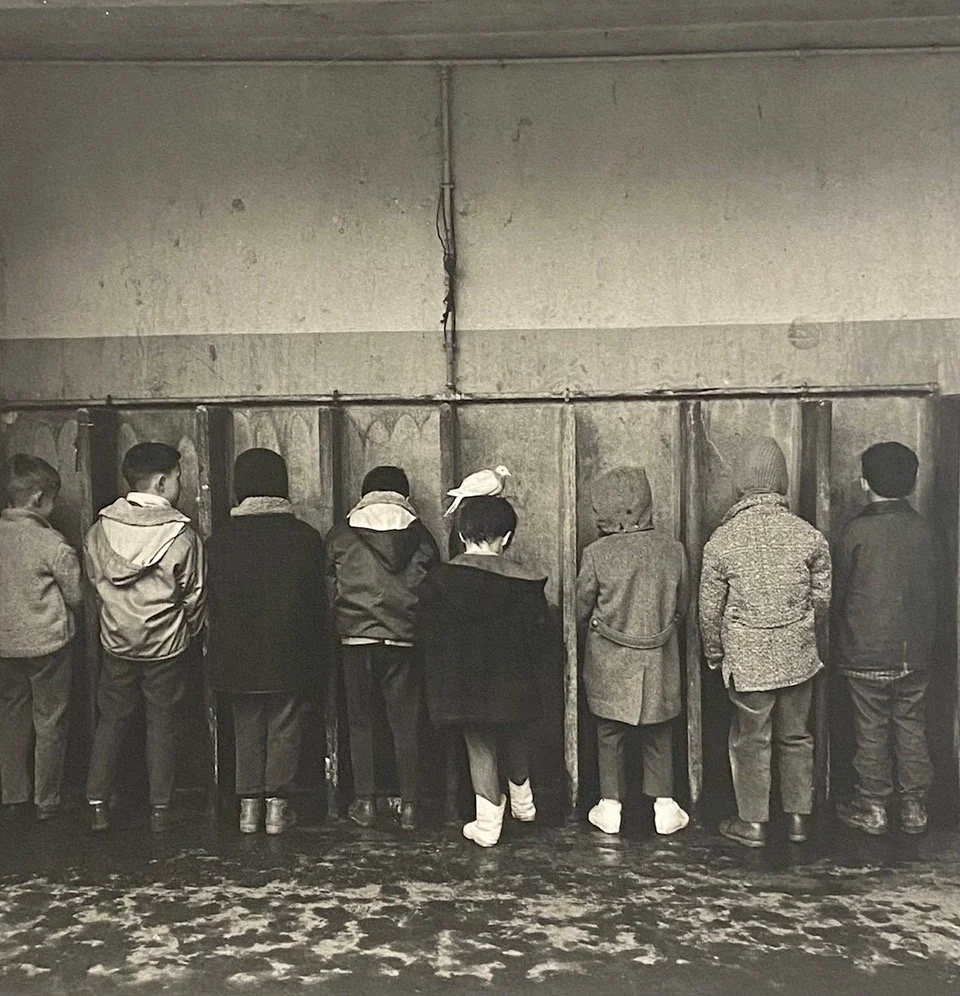

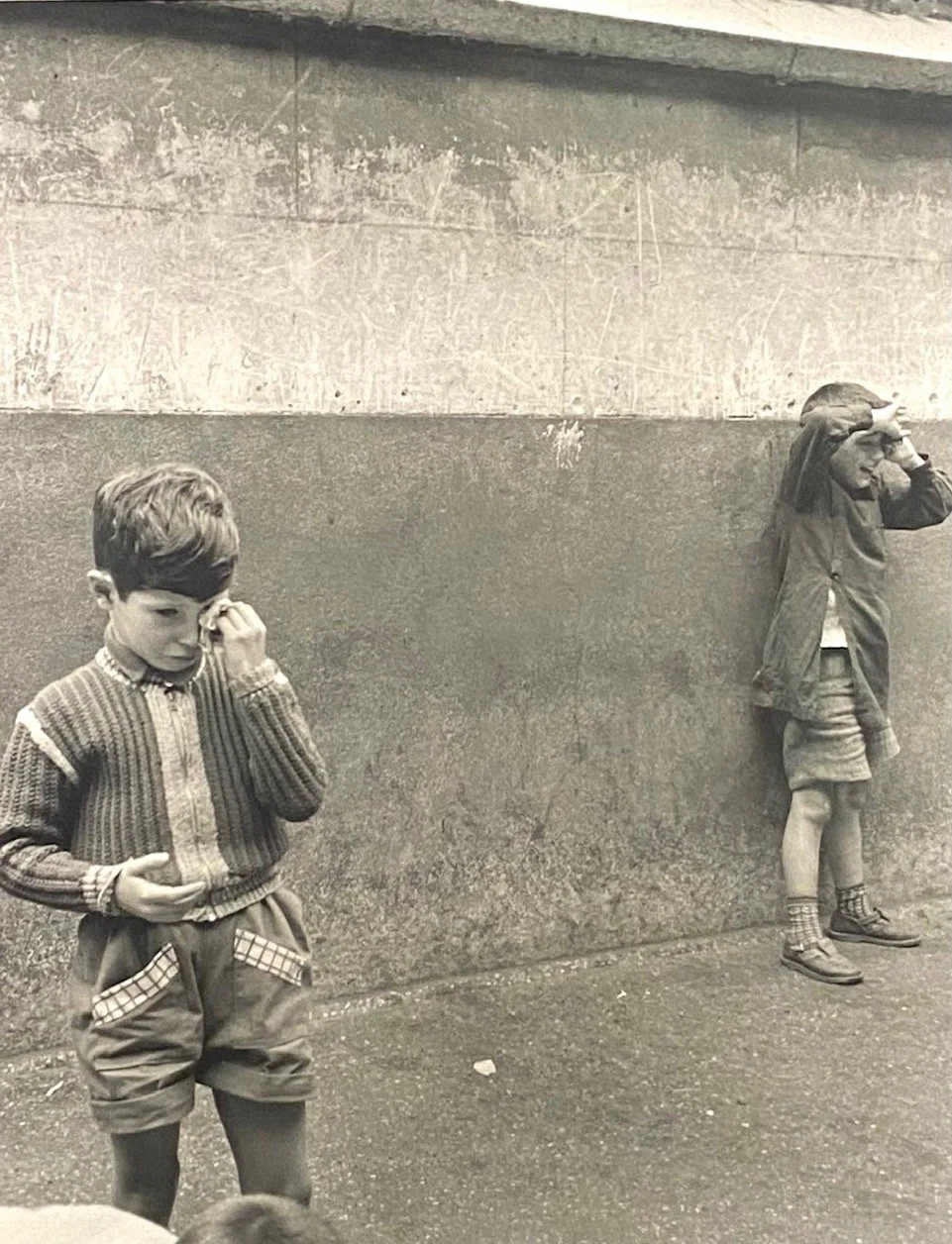

The images in the exhibition are organized by subject, beginning with children: “His tender connection with children remained constant. He shared their love for play, an irrepressible need for freedom, and the joyful insolence that stayed with him into his later years.” Here is how Max Kozloff (Artforum, 1983) describes Doisneau’s photos of children. “On the whole, children are pictured from further away than are adults, as if to have gotten closer would have been really intrusive.…One notices the dinginess of the suburban setting, the mud on the cobblestones, and the child’s wrinkled leggings… Though natural performers, children have not yet learned guile nor given up their native dignity. Perhaps that is why Doisneau views them as existing in a state we once knew but can never re-enter, and therefore with a sense of loss that can only be poetic.”(Figs 13-18)

Figure 13. Little boys lined up to pee and a pigeon on the head of the littlest boy!

Figure 14. Boys running with Eiffel Tower in background

Figure 15. Children holding onto each other’s jackets as they cross the street

Figure 16. Boys ringing doorbell and fleeing

Figure 17. Boy and his baguette

Figure 18. Boys playing on remains of a car

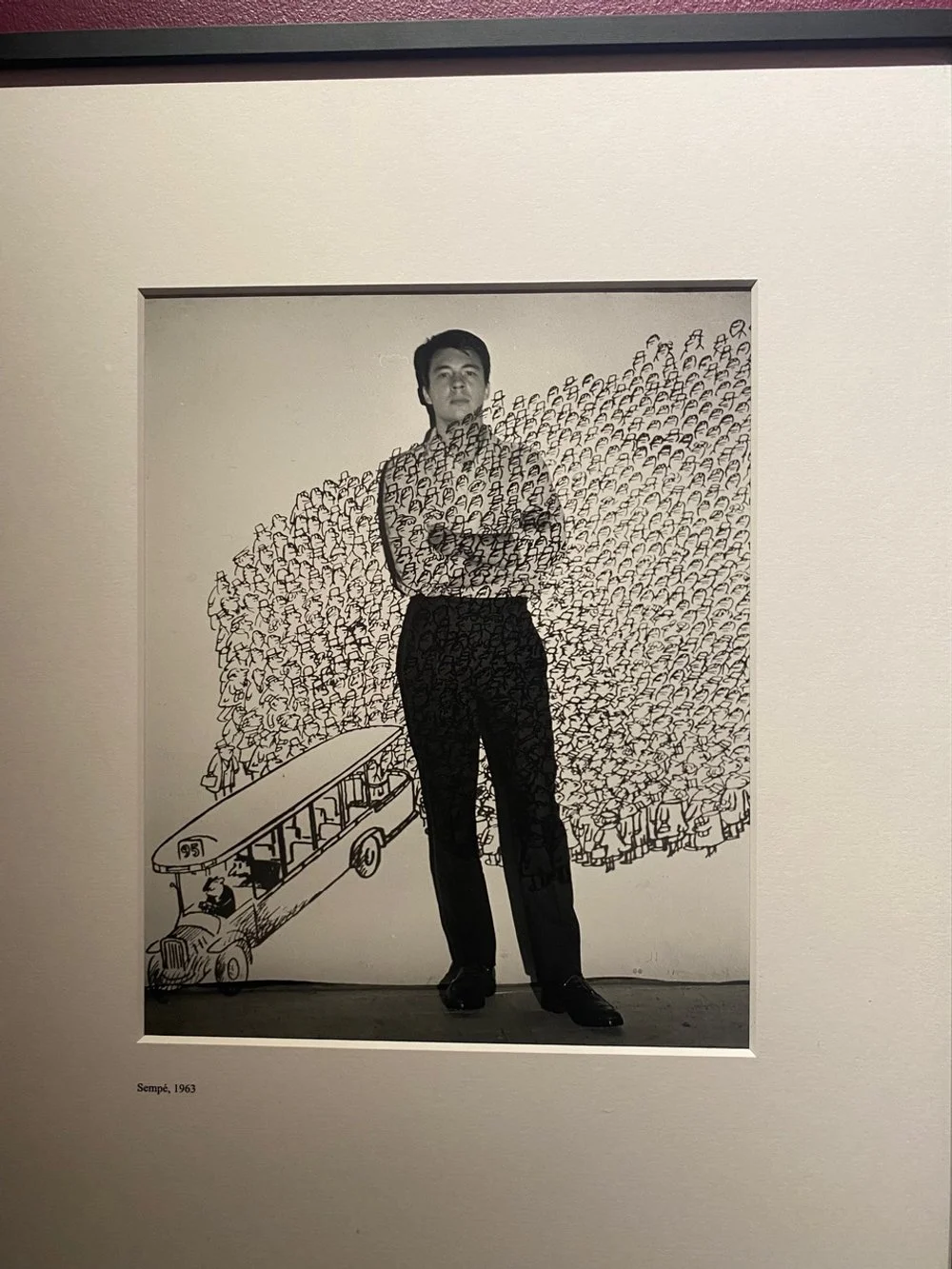

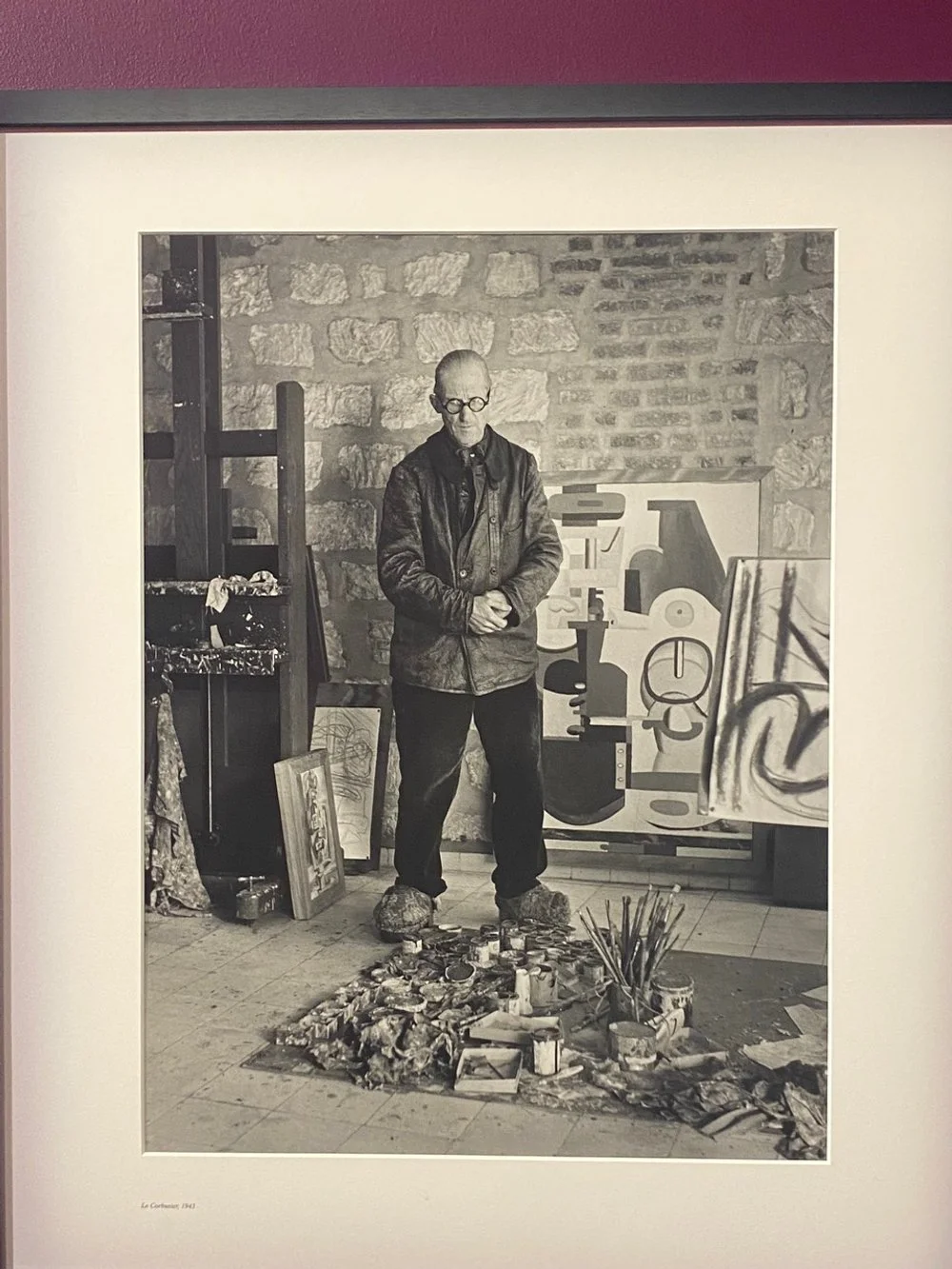

In another section are photographs of artists in their studio, including some of the best known artists of his time and ours. To take those photos, Doisneau had a ring side seat because in 1937, he and his wife moved into a painter's studio in Montrouge where they lived for the rest of their lives. Fernand Léger had a studio in the adjacent building and Georges Braque, Alberto Giacometti and César lived nearby. Doisneau also took photos of Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and David Hockney. And yet, he hesitated to “knock on the doors of his illustrious neighbors” because “I would never have had the audacity to ask for time from those who have used it so well. To the great masters whose names are chapter headings in art history books... Yet some of these great masters pushed me by the shoulders into their studios.” (Figs 19-24)

Figure 19. Fernand Léger

Figure 20. Sempe

Figure 21. Niki de Saint Phalle, 1973

Figure 22. Jean-Paul Riopelle, 1956

Figure 23. Picasso at Mougins, 1963

Figure 24. Le Corbusier, 1945

Another category of photographs are those he made of or with writers. According to the curators, “writers were essential companions in his life as a photographer. With them, he enjoyed recreating his own little theatre, whether on the street, in a café, in a private flat, in a studio, or in his own…” He met the poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert in 1931. Fifty years later he recounted their first meeting to the journalist Francois Cavanna, with whom he wrote Les doigts pleins d'encre (Ink-Filled Fingers). ”By the time night came, I'd learned that it only takes a day to make a childhood friend.”

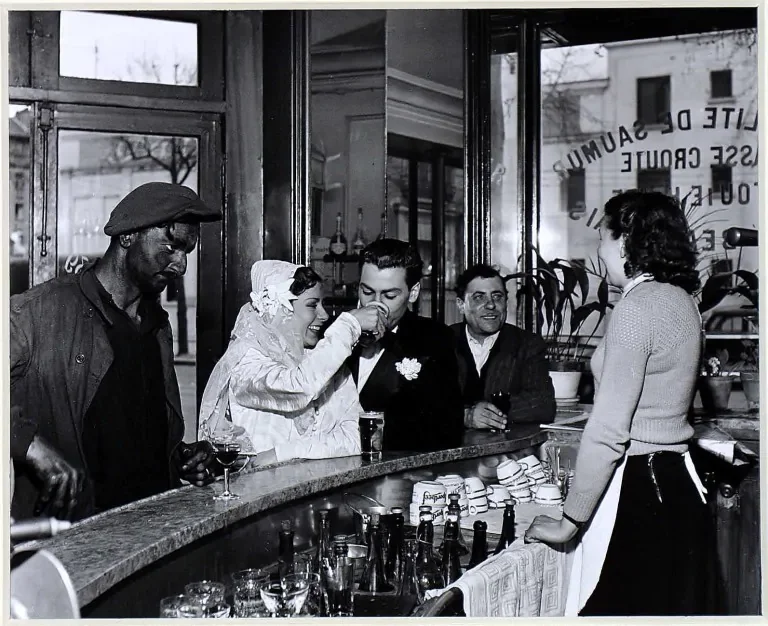

His 1945 meeting with poet Blaise Cendrars led to the publication of Doisneau’s first book, La Banlieue de Paris. His association with the journalist, poet and writer, Robert Giraud, opened the doors to bistros and many other places where cameras would otherwise have been discouraged if not outright banned, like the Tabac de l'Institut on rue de Seine and Fraysse's in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the Café Curieux on rue Saint-Merri in the Marais district and Aux Chasseurs on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis. (Figs 25-26)

Figure 25. Bistrot Noir et Blanc, 1948

Figure 26. At the Café, Chez Fraysse, 1958

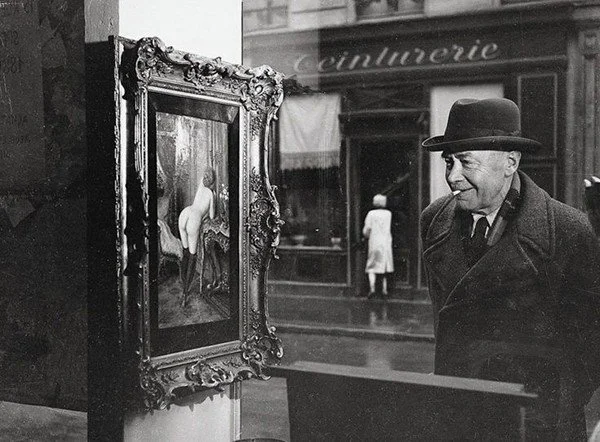

In 1948, Robert Giraud suggested another venue. As caretaker of Romi's gallery on rue de Seine, Giraud noticed that one painting was provoking some comical reactions. Doisneau checked it out. “Comfortably seated in a soft armchair, with my camera resting on a piece of furniture, I could see through the mirror, whose reflections made me invisible, the movements and reactions of the various iconolaters.” (Figs 27-29)

Figure 27. An admirer looking at painting in Galerie Romi, 1948

Figure 28. Another couple of admirers at Galerie Romi, 1948

Figure 29. Sideway glance at Galerie Romi, 1948

A few years earlier, Doisneau had positioned himself in front of the Louvre to look at people looking at the Mona Lisa. It was before there were lines to see the painting and glass on the painting and guards around the painting. The subject of Doisneau’s photos, was not the woman with the enigmatic smile, but the expressions of the visitors, as they tried to understand (or explain) what all the fuss was about. (Fig 30)

Figure 30. Boy explaining Mona Lisa to girl, 1955

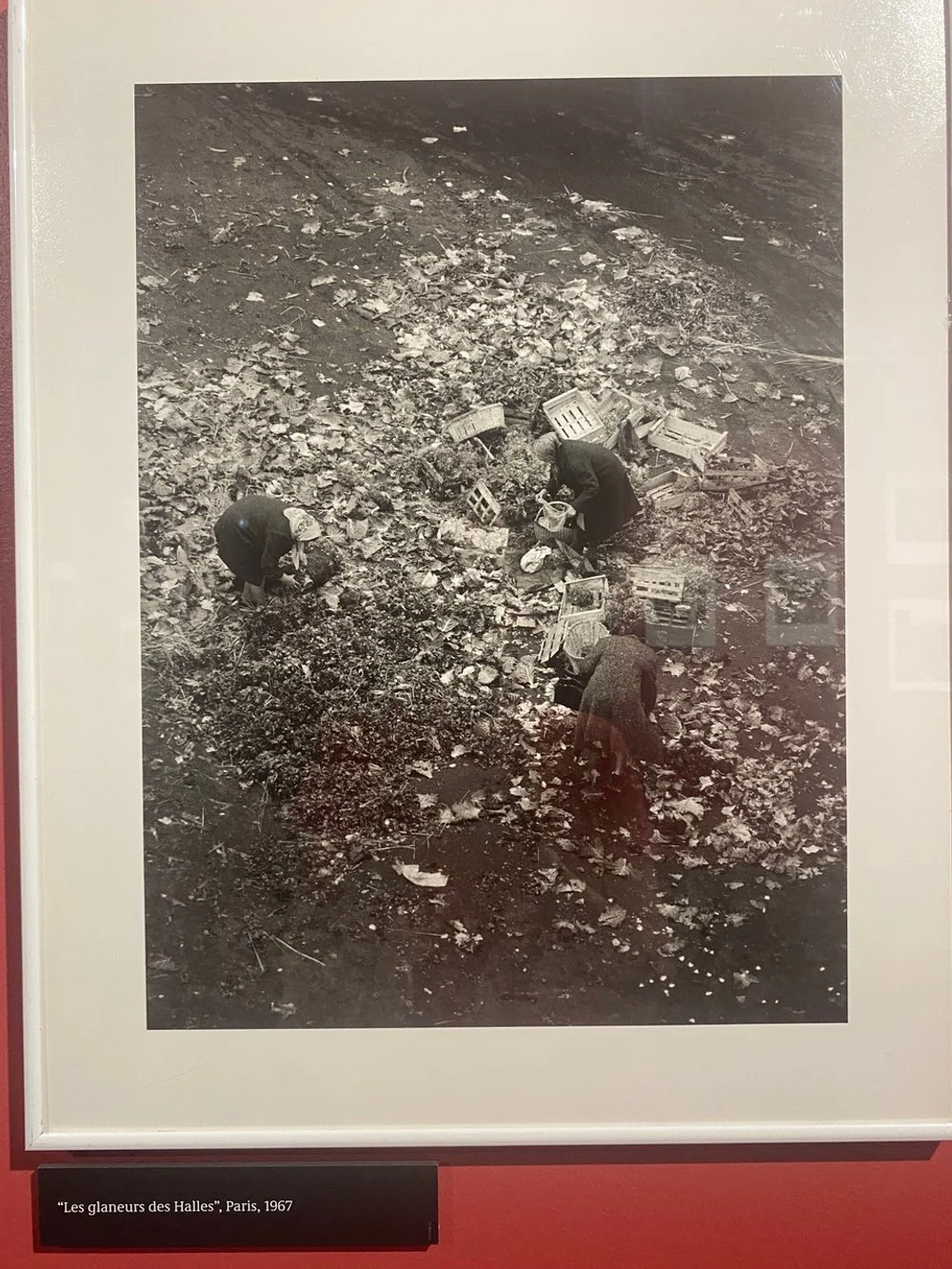

In an interview with Marion Kalter from 1982, Doisneau explained that, “The areas I love most in a city are those that have curves. When the lines are too straight,…there is no improvisation. When a child slides down the railing of a staircase, when you string a bicycle against a fence, you change the original use of these objects : then it becomes tender and human, and that is what i like… Can you imagine Les Halles in the center of Paris with those tiny streets ?… The trucks needed a lot of good will and energy to get to Les Halles. It was the only « quartier » where you could « tutoyer » the police. The workers are really the motor of a city. Thanks to them a city functions. They are the ones who create the real atmosphere of a city and I feel well with them, they are people like myself.” (Figs 31, 32)

Figure 31. La Marchande des Fleurs, Les Halles, Paris, 1968

Figure 32. Les glaneurs des Halles, Paris, 1967

I’ll let Max Kozloff (Artforum, 1983) have the last word/s because I completely agree, “Many of the people shown in (Doisneau’s photographs) act as straight men or women—that is, as mock victims in a comedy. They’re the ones to whom unfortunate things happen, but whose dignity is never ruffled. They’re never compromised nor wounded by the frequent jokes made at their expense, but they’re never fully alert to them, either…Doisneau makes us laugh at (the situation, the people) but as we do so we also laugh at ourselves.…Doisneau’s subjects are either endearingly oblivious to the illogic of their situation or else they tolerate it very well . . . which is even funnier… To walk through Doisneau’s city is to be foiled or undone in special ways, at any moment. At the same time, his courtesy is not only disarming, it’s positively inviting, a mark of sly wit….”(Figs 33, 34)

Figure 33. Two Boys Crying

Figure 34. Quatorze Juillet au Tuileries, 1978

Doisneau’s kindness and empathy for and with his fellow human beings are a salve to the spirit which is much needed these days. The photographs in this exhibition will bring a smile to your face and maybe a tear to your eye. Gros bisous Dr. B.