‘Dad and Mom, Don't Worry About Us, We Are All Well.’

Objets divers et variés 百货 (bǎihuò), Song Dong at Le Bon Marché (through 22/02/26)

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. I said goodbye to Nicolas a few days ago. He had flown in from Xi’an, China to help me prepare my old pigeonnier for its new owners. And gather a few objects, to put into boxes and ship by post to Paris or put into the two suitcases we brought with us on the train. Ginevra and I had discussed putting some furniture into a storage unit. But common sense prevailed, it was a trap I didn’t want to fall into. Paying to store stuff I had no idea if I’d ever be able to use made no sense. In the end, I sold, gave away or left for the new owners, everything Nicolas and I could neither box nor take with us. Except for the two chairs Ginevra upholstered and Nicolas spray painted. Guy, the brocanteur from whom we bought so many things, has put the chairs aside for us to pick up one day…..

I saw the exhibition that I am going to tell you about before Nicolas and I left for the Dordogne. It may have played a role in my decision to leave so much of the stuff I had accumulated over the past 30+ years, behind. To understand why, keep reading!

Today, we’re back to the exhibition I mentioned last week, at Le Bon Marché. Where, since 2016, a contemporary artist has been invited to fill the exterior windows, the grand central atrium and part of the second floor, during the annual January White Sale. Each guest artist creates an exhibition that is monumental enough to impress but not so overwhelming that it gets in the way of what people come to Le Bon Marché to do, shop.

This year, Le Bon Marché chose the Chinese conceptual artist, Song Dong to create an exhibition, the title of which is ‘Objets divers et variés (Various and varied objects).’ The first thing you see as you approach the store is a huge poster mounted on the facade. It is a photograph of the artist and is part of an ongoing series of self portraits he is creating each month to document the changes in his physical appearance. “The idea (according to Song) is to show, through this series of self-portraits, how our faces …. change radically depending on circumstances and situations….” For January 2026, he depicted himself as a salesman or doorman of a department store, dressed in a black suit. The sketch of the object behind him will make sense once you get inside.(Figs 1, 2)

Figure 1. The facade of Le Bon Marché

Figure 2. Self Portrait, Song Dong, January 2026

But first the outside. The store windows along Rue de Sèvres, Rue de Babylone, and Rue du Bac, are covered by what looks like old and worn painted wood. Each faux, trompe l’oeil wall is pierced by various square openings, like windows. As you peer into these windows, you are dazzled both by the light of hanging lamps and the reflective surface of the background mirrors. They highlight the objects in the windows. Each window has a different category of object. In one window there are telephones, among them clunky landlines and chunky cell phones. In another window are thermoses that Nicolas explained to me, are ubiquitous in China. People carry them wherever they go (he had one with him) filled with hot tea. Behind the door of another window were radios and behind another, record players, and so on. (Figs 3-6)

Figure 3. On the exterior vitrines, one of the faux doors cover the through which you can see what is behind

Figure 4. Assemblage of telephones

Figure 5. Assemblage of thermoses

Figure 6. Assemblage of radios and recording equipment

As I looked at the objects in the vitrines, a veritable visual history of those objects from the 19th century until the present, I wondered where the artist got all of them. I learned that some of the objects are from his own collection. But most of them are borrowed. Le Bon Marché put out a call last October, to customers and partners and employees, asking for specific types of objects, from which Song Dong and his team selected what they wanted to include in the exhibition. And so, we are told, the exhibition became a “collaboration (of) individual stories and Art History,” as well as the story of the role that Le Bon Marché has played in the lives of Parisians for more than 150 years. Supplying, presumably, lots of stuff that lots of people bought. Once the objects were selected for inclusion in the exhibition, they were no longer everyday objects. They “were elevated from the mundane to the unique." Separated from their original function, “they highlight instead the fragile boundary between use, memory and value.” I’ll tell you more about how these groupings of objects came into being in a moment.

These objects, we are told, also pay “homage to Marcel Duchamp's concept of the ready-made.” You may be familiar with the urinal Marcel Duchamp bought in New York, in 1917 which he called, Fountain. And which he submitted for the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York. He didn’t present it exactly as he found it, he hung it at an angle that would have made it useless as a functional object. He signed it R Mutt, almost but not exactly the name of the manufacturer, R. Mott The urinal was one of Duchamp’s early readymades, but it wasn’t his first. That was the bicycle wheel which was followed by the bottle rack, which he bought at a department store in Paris in 1914. Without altering it one bit, he proclaimed this common, mass-produced item a work of art. He called it a ‘readymade,’ which he defined as an ordinary object (either found or mass-produced) that becomes art when an artist says it is art. (Figs 7, 8)

Figure 7. Urinal ‘readymade’ Marcel Duchamp (R Mutt) 1917

Figure 8. Bottle Rack, readymade, Marcel Duchamp. 1914

It is the bottle rack, the original which was tossed out by Duchamp’s sister, copies of which are in museums all over the world, that Song Dong’s two chandeliers, in the atrium of the grand central space, on either side of the escalators, refer. Song Dong’s bottle racks are monumental (7.5 m [24’7”] high and 6 m 19’8”] wide). (Figs 9 - 11). But Song has played with more than scale. His bottle rack refers to its original purpose - it includes bottles! “Composed of steel rings and bottles, these pendant lights engage with the architecture of the space and remind us of how an object can be transformed, with a simple shift in perspective, into a work of art.” They reminded me of Claes Oldenburg whose everyday objects on a monumental scale got us asking, as Duchamp did before him, and artists like Song Dong do now, the big questions, like what is art and what gives meaning to an artist’s work. (Fig 12)

Figure 9. Chandelier, from below, Song Dong, 2026

Figure 10. Chandelier from the escalator, Song Dong, 2026

Figure 11. Chandelier looking down, Song Dong, 2026

Figure 12. Shuttlecock, Claes Oldenburg

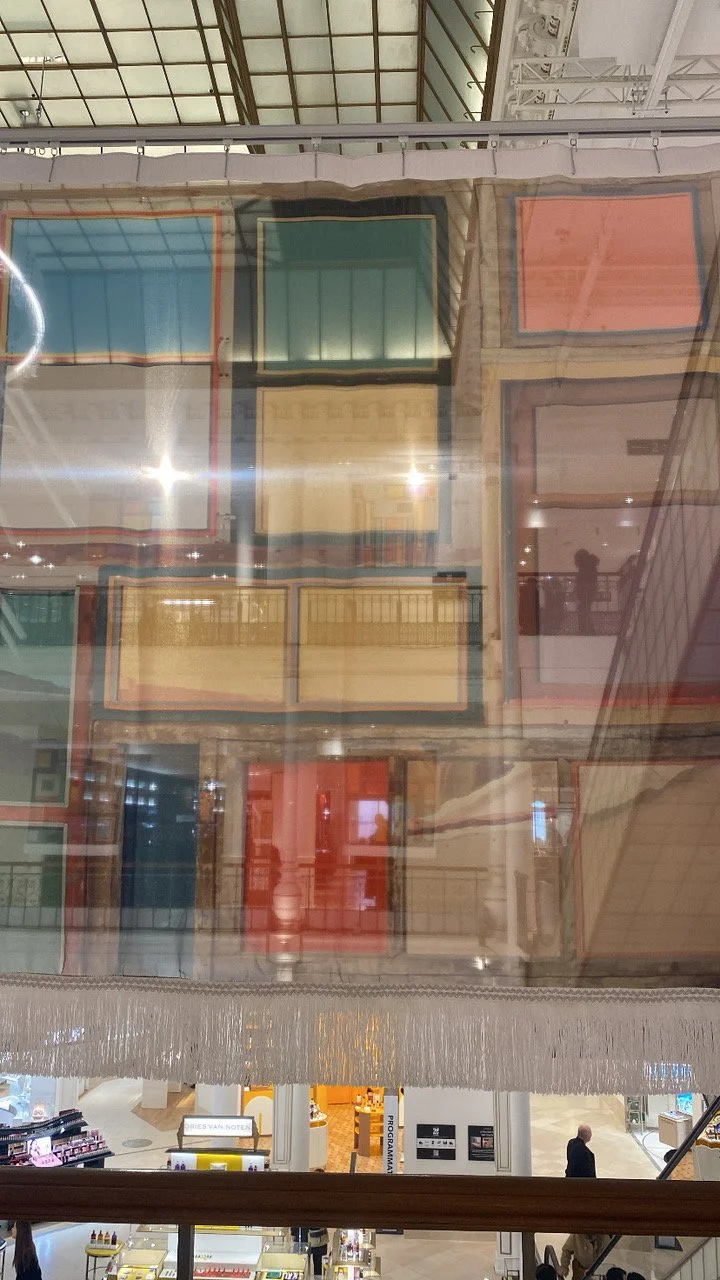

Diaphanous curtains, echoing the faux wooden doors and windows on the exterior, are hung around the atrium. They bring the outside, in and give us an opportunity to see the faux exterior walls in a different way, in a different material. (Fig 13)

Figure 13. Diaphanous curtains hung around the atrium, Song Dong (see also Figure 10)

On the second floor, are mirrored ‘fun houses’ which, according to the Pace Gallery which represents Song, “draw on the concept of mirrors in traditional Chinese feng shui while philosophically exploring the idea of ‘borrowing,’ prompting viewers to contemplate humanity’s transient existence on Earth. This immersive hall of mirrors, made of salvaged doors and windows, invites visitors to lose themselves in reflections, in houses illuminated by hundreds of lamps that blur the line between reality and illusion.” (Artthat, 09/2025).

Visitors are welcomed to enter both of these structures. One is more disorienting than the other. The walls and ceiling and floor are mirrors. I hesitated before stepping into the space, before walking onto the mirrored floor. Once inside, I had the sense that I was walking on a void, that nothing was holding me up. Hanging from the mirrored ceiling are lots of lamps. We see their reflections and our own on the mirrored walls. One reviewer noted a similarity between these mirrored spaces and Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms. I have been in quite a few of Kusama’s Infinity Rooms. In them I have experienced a sense of joy rather than disorientation. The second structure was much less disconcerting. Although the floor is mirrored, the walls are pierced by windows, from which you can look out and orient yourself in the reality of the store beyond. (Figs 14-18)

Figure 14. Looking across the mirrored structure

Figure 15. Me, finally inside the mirrored structure

Figure 16. The mirrored structure was filled with lamps

Figure 17. Song Dong in the Mirror structure

Figure 18. Infinity Room Yayoi Kusami

Now I want to give you a context for the objects in the vitrines that I discussed earlier. And for that, I must tell you a little about the artist and his family’s history. Song Dong was born in Beijing in 1966, the same year that China’s decade long Cultural Revolution began. The Cultural Revolution was launched by Mao Zedong with the goal of strengthening Chinese Communism by purging remnants of capitalism and traditional Chinese elements from society. The revolution was violent. There were massacres in Beijing, Yunnan, Hunan and elsewhere. Death toll estimates range from 1 to 2 million people. Much of the chaos and violence was perpetrated by the Red Guard, a student-led, paramilitary movement mobilized by Chairman Mao in 1966. Their mission was to destroy the Four Olds (old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits). As part of this purge, they destroyed historical artifacts and cultural and religious sites. Millions of Chinese people were persecuted for being members of the ‘Five Black Categories,’ which included landlords and rich farmers. Intellectuals and scientists were included in the Stinking Old Ninth and they, too (or especially) were subjected to condemnation, imprisonment and even execution. The country's schools and universities were closed, the National College Entrance Exams were cancelled. Over 10 million young people from urban areas were relocated to the countryside for re-education.

That was the China into which Song Dong was born. His mother’s family had been wealthy. They lost everything after one family member was jailed as an anti-Communist spy. Song Dong’s father Song Shiping was one of the millions of Chinese sent to re-education camps for supposedly being a "counter-revolutionary". He was held there for seven years during which time, Song Dong, his sister and his mother waited and worried.

Once Song’s father returned, both of his parents adhered to the Cultural Revolution’s insistence on frugality. Song’s mother took her vow of frugality to an extreme. She refused to throw anything away. Even as she accumulated new stuff, she did not dare to discard the old stuff. Everything she managed to obtain, she retained. Stuffing more and more stuff into their tiny Beijing house. Even after her children were grown, even after her husband died in 2002, Song’s mother continued to “obsessively bring more stuff home as if continuing to feather a nest for a now-absent family.”

Her hoarding reminded me of well known American hoarders, like the Collyer brothers and Jacqueline Kennedy’s cousins, Big Edie and Little Edie Beale of Grey Gardens. But those were wealthy people who became increasingly eccentric. Song Dong’s mother became a hoarder following traumatic upheavals in her life - her family’s loss of status and money, her husband’s incarceration. Holding onto stuff even after she no longer needed it, must have been a comfort. I was reminded of an interview I heard on NPR many years ago, with a wealthy woman who lived in Los Angeles. She told the interviewer that she always carried a sandwich in her purse. Because of the unbearable hunger she could never forget, the hunger she experienced as a young girl on a train taking her and her family to Auschwitz. Would that ever happen to her again? She didn’t know. But the sandwich in her purse was a talisman, insurance against that hunger.

Song Dong has explored questions of memory, time and consumption through everyday objects since the 1990s. I suppose living in a house crammed full of stuff could have made him into a minimalist but it didn’t. Stuff became the essence of his art. After his father died, Song was finally able to convince his mother to move into an apartment. He promised her that nothing she had saved would be discarded. That he would preserve everything and make it meaningful by making it into art. His mother agreed and with the help of his wife, also an artist and his sister, they emptied the family home.

In an exhibition space in Beijing in 2005, they sorted their home’s contents into groupings, stacks of neatly folded shirts, bottles and cans, stuffed animals, etc. which they arranged in and around a dismantled section of their original wooden house. Song had a neon sign made on which he wrote, ‘Dad, don’t worry, Mum and we are fine.’ In 2009, his mother died after she fell from a step ladder trying to save an injured bird in a tree in a park near her new home. Since then, Song Dong shows his filial piety with an updated neon sign, ‘Dad and Mom, Don't Worry About Us, We Are All Well.’

Song Dong called the exhibition ‘Waste Not,’ the title taken from the Chinese adage wù jìn qí yòng (物尽其用), which can be loosely translated to the English adage, "waste not, want not" but which is more literally translated as, "anything that can be somehow of use, should be used as much as possible”. Waste Not has traveled to museums around the world - New York, London, Dusseldorf and Sydney. In a museum, the objects are arranged in neat rows or piles, ordered by use and type. They become a miniature city for visitors to walk through. (Figs 19-20) At Le Bon Marché, we look into vitrines at groups of objects, it’s not the full experience, rather a taste of it.

Figure 19. Waste Not in Beijing, 2005

Figure 20. Waste Not, Carriageworks, Sydney, 2013

Song Dong continues to add onto his mother’s collection with stuff he finds on the streets of Beijing, discarded furniture, architectural elements, everyday objects, “remnants of people’s homes (that) carry with them the history of a city and the lives of its people,” Through a “veritable landscape of commodities,” Song’s Waste Not installation “evokes notions of home, belonging, security, and migration while exploring the relationships between memory and fact; humor and trauma.” ‘Waste Not’ is, according to Pace Gallery, the gallery that represents him, an act of physical and psychological unpacking.

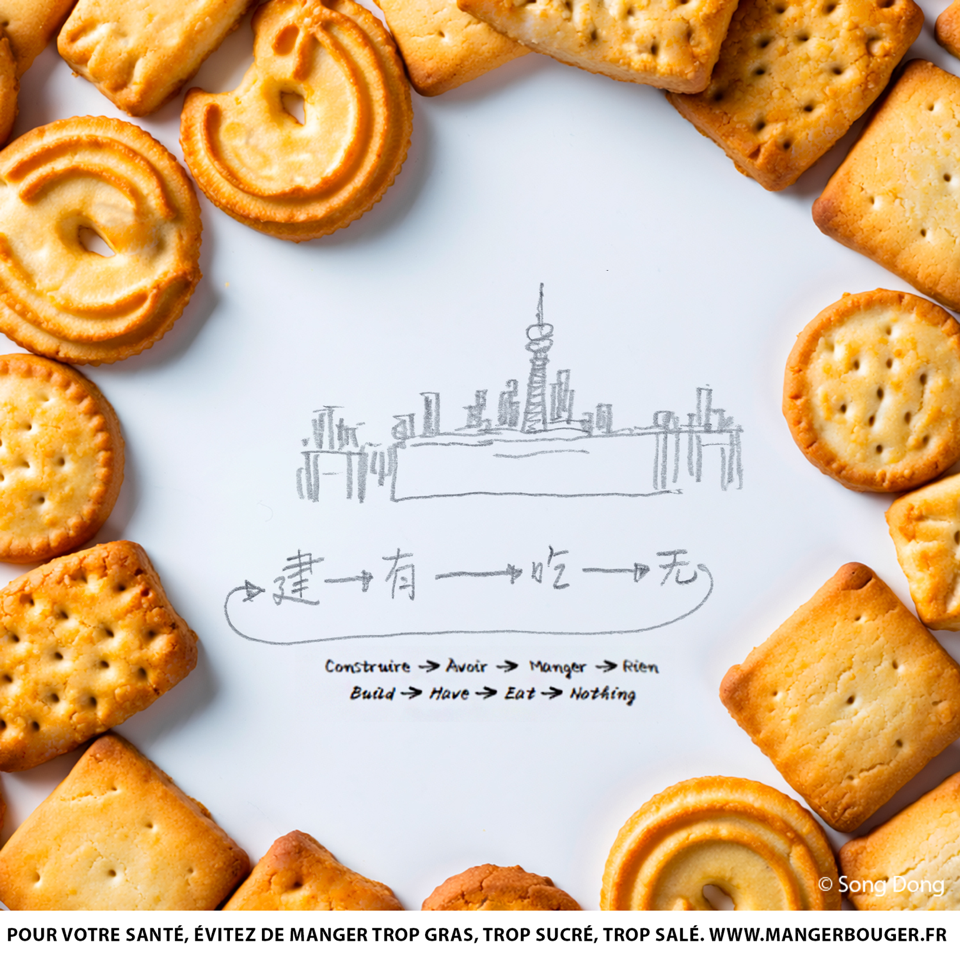

The final part of this temporary exhibition hasn’t started yet and when it does, it will be very temporary. Beginning on February 18 and for three days only, visitors can see, EATING THE CITY: EVERY DAY IS TOMORROW, “an imaginary metropolis made from cookies, sweets, and chocolates.” It’s an installation that will become performance art on February 21st at 17h00, when it will be destroyed, that is when it will be ‘eaten’ by everyone who pays to participate (which I have). We will “collectively destroy and consume” the biscuit / chocolate city, and as we do, we will “reflect on urban transformation and on our relationship with the ephemeral, creation, and destruction.” This performance piece has already been staged in Barcelona, Beijing, Hong Kong, London and Shanghai. According to the artist, the point “is for the city I build to be destroyed ... As cities in Asia grow, old buildings are knocked down and new ones built, almost every day ... My city [is] tempting and delicious. When we are eating the city we are using our desire to taste it, but at the same time we are demolishing the city and turning it into a ruin.” I’ll let you know how it goes next week. (Figs 21, 22)

Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 21. Eating the City

Figure 21. The Eating the City that I will participate in later this week. This disclaimer about eating wisely is on every advertisement for any kind of food sold in France.

BONUS:

Borrowed Light exhibition in Sao Paolo, 2025

Another exhibition by Song Dong in a museum with a lot more space for the mirror magic to happen