inspiration, creation and sharing

Le Paris d’Agnès Varda de-ci, de-la. Musée Carnavalet

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week: the Angès Varda exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet. Before this exhibition, I knew very little about Agnès Varda. About a decade ago, when Nicolas was taking a film class at art school, we watched ‘Cléo from 5-7’ together. I had never taken a film class, so his syllabus was a good introduction for me. But since I hadn’t attended the lectures, I watched the film without knowing why it was important or what it was about.

I don’t think I heard Varda’s name mentioned again until 2022, three years after her death. The Cannes Film Festival honored her by changing the name of one of their screening rooms to Salle Agnès Varda. Maybe hearing isn’t the right word, listening is more like it. It was because JR, the photographer and street artist about whom I have written, seemed to be everywhere at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival. Because, as it turns out, in 2017, JR and Varda, 55 years his senior and 89 years old at the time, took a road trip through rural France and made a film documenting the people they met, in the way JR always does, by taking photos, blowing them up and plastering them on buildings all over town. Also in 2022, the one television show I watch in Paris, Quotidien, dipped into their archives and featured a few of the segments on which Varda appeared. Like when she showed up with her honorary Oscar wrapped in a kitchen towel. And yet, in 2023, I missed her retrospective at La Cinémathèque française in Paris. I have no excuse.

Then just this year, my friend L. John Harris included a long excursus on Varda’s film, ‘The Gleaners and I’ in his memoir, which I reviewed a few weeks ago.

Although this exhibition ostensibly focuses on Varda’s career as a photographer, the curators concede that Varda’s three interconnecting careers: photographer, filmmaker, and visual artist, cannot be separated. Since the exhibition is at the museum dedicated to the history of Paris, the focus is on the ties Varda forged with Paris (mostly).

Varda was not a Parisian by birth, she wasn’t even French. She was Belgian, born in Brussels in 1928. In 1940, when the Germans invaded Belgium, the Varda family joined millions of others and fled to the unoccupied South of France. They settled in a small seaside town, called Sète. Here Agnès Varda formed two critical connections that set the direction of her personal and professional life. One was to the place, Sete, the subject of her first film, “La Pointe Courte, (1954)“ The other was to the Schlegel family. Agnès became romantically involved with her classmate, Valentine Schlegel and professionally involved with Valentine’s brother-in-law and Sète native, Jean Vilar.

But that was in still in the future. In 1942, when all of France fell to the Nazis, the Vardas moved to Paris. Two years later, after the Liberation, Varda enrolled at the École du Louvre. She studied art history, archeology, painting, philosophy and literature. She was planning on becoming a museum curator. But she changed her mind and her direction when she began taking photography classes at night. With a second hand Rolleiflex that her mother bought her, she decided that photography would allow her to combine her intellectual interests with a manual activity. She decided to become a photographer.

In 1948, six years after Varda left Sète, Jean Vilar, by then a prominent theatre director, invited Agnès to help him with his new theatre festival, in Avignon. She became the Festival’s unofficial photographer. Three years later, Vilar became head of the Théâtre National Populaire, in Paris. He hired Varda to be that theater’s photographer, too.

Unlike photo-reporters who go on assignments all over the world, Varda photographed artists when they came to Paris. She devised and discovered many quirky settings. Her photos are mostly humorous and strange, sometimes also a little dark. A photograph of the photographer Brassai shows him in front of a decrepit wall. When Federico Fellini was in Paris to promote his film La Strada, Varda took him to a demolition site near her home and photographed him, ‘half-hidden in trenches of stone debris.’ As for her photograph of the sculptor, Alexander Calder, she had him crossing the street in front of her studio, carrying a mobile, laughing. (Figs 1-5)

Figure 1. Brassai, 1954

Figure 2. Federico Fellini, 1956

Figure 3. Fellini back left, guy doing what guys do when they see a wall, near right, 1956

Figure 4. Alexander Calder walking across the street holding one of his mobiles, laughing, 1952

Figure 5. Agnès’s niece wearing angel wings, walking around Paris, 1955

Paris was Varda’s crucible and incubator. Much of her work was done in a single space where neighbors and family; friends and fellow artists, crossed paths. Where her clients called and her children played. For 70 years, from 1951 until her death in 2019, Varda lived at #86 rue Daguerre. Varda said: "I don't live in Paris, I live in the 14th arrondissement of Paris." Rue Daguerre was the perfect address for her, named as it was after Louis Daguerre, the inventor of the Daguerreotype, the first publicly available photographic process, used in the 1840s and 1850s. (Figs 6-7)

Figure 6. Agnès Varda’s home/workshop/studio, 86 rue Daguerre, Paris

Figure 7. Agnès Varda in courtyard of her home, 86 rue Daguerre

This is how Varda came to live and work on rue Daguerre. In 1950, Varda’s engineer father had a financial windfall. He bought each of his 5 children an apartment. Agnès didn’t want an apartment. She wanted, according to her daughter, ‘a workshop, laboratory, studio for her photographic practice.” And that’s what she created at 86 Rue Daguerre, an impasse near Montparnasse. Agnès’s gift from her father was two adjacent empty shops, one an abandoned grocery store and the other, a derelict framer’s shop, with an empty gilding workshop upstairs. Between them was a courtyard-alley with a doorway opening onto the street. The shops were rundown, there was no indoor toilet. She and Valentine Schlegel moved into the former grocery store. The framing workshop became Valentine’s ceramics studio. When she left in 1957, Agnès transformed it into a photographic laboratory. The gilding workshop became Agnès’s studio. Its glass roof provided the natural light Agnès preferred. Here, she photographed friends and family and eventually, actors who wanted a different kind of professional portrait, one with natural light and without sophisticated poses and makeup. (Fig 8)

Figure 8. Recreation of Varda’s studio in which there was a bench, a stool, a Calder mobile and a pair of gilded angel wings

The surprising and unexpected were leitmotifs of Varda’s life and oeuvre. Surrealism and chance were her touchstones. The exhibition begins with an opened notebook on which Agnès wrote the names of métro stations. Circled letters form new words. (Fig 9) The curators write that ‘the result is often unexpected, funny, and even poetic’. When I saw it, I was reminded of a poetry course I took at the U of Pennsylvania, called Modern Poetry. (ModPo) One week we studied aleatory poems, poems that are created by chance. For example a poem created by deleting every second word from a random text or from cutting up a text and putting the words together randomly. For me, the exhibition opened on a felicitous note. I was happy with my memory and happy to see how Agnès transformed names of metro stops into poetry.

Figure 9. Handwritten list of métro names with parts of words circled to create new words

When Agnès was 25, having seen (according to her) fewer than 25 films, she decided to make a movie. It was called and was about “La Pointe Courte,” a fishing village in Sète, where her family lived when they first moved to France. The project was almost entirely self-financed. The actors Philippe Noiret and Sylvia Monfort worked for free and Alain Resnais, who directed ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour,’ edited the film for her. (Figs 10, 11) He also introduced her to some of his friends, like Jean-Luc Goddard and François Truffaut. Although the film was not commercially released, screenings of it brought Agnes to the attention of other film makers. Carrie Rickey, the author of a 2024 biography of Varda contends that it “failed to be acknowledged as the first film of the New Wave, only because Varda was too far ahead of (the New Wave). Other aspiring young French filmmakers, including her new friends, weren’t ready to follow in her footsteps…. When she knew the men a little better she realized that ‘their influences were movies.’ Hers were ‘paintings, books . . . life.’” FYI: New Wave is a film movement that emerged in the late 1950s. It was characterized by a rejection of traditional filmmaking conventions in favor of experimentation in editing, style and narrative. The New Wave filmmakers also engaged with the social and political upheavals of their era.

Figure 10. Agnès filming La Pointe Courte

Figure 11. Poster for La Pointe Courte with Philippe Noiret & Silvia Montfort who worked for free

In 1961, Varda made her second feature film, “Cléo from 5 to 7.” She had wanted to shoot it in color and film it on location in France and Italy. But her producer told her to “make a little film in black-and-white.” So she did. Filmed only in Paris and mostly in places within walking distance of her home, her cast included friends (Godard and Anna Karina) and sort-of family, the father of her first child, Antoine Bourseiller, whom she left when she was pregnant. The movie is about a young woman, Cléo, a singer who wanders through Paris from 5 to 7, waiting for test results to see if she has cancer. In France, "cinq a sept," (5 to 7), has a specific meaning - it’s when Frenchmen traditionally saw their mistresses, after work and before heading home for dinner with their families. The film starts on rue de Rivoli then moves to the crowded Left Bank. Cléo stops for a drink at Le Dôme and ends up in the Parc Montsouris, both in the 14th. (Figs 12-14)

Figure 12. Scene from Cléo from 5 - 7

Figure 13. Map in the exhibition showing various places in Paris where Cléo de 5 à 7 was filmed

Figure 14. Poster for Cléo de 5 à 7

Towards the end of ‘Cléo from 5-7,’ Varda inserted a little silent film, The Lovers of MacDonald Bridge,’ (Fig 15) shot at the Canal de l'Ourca, which I know because Nicolas and I go there to check out the graffiti. When Agnès made her film, it was more industrial with boats and bridges, quays and warehouses. Here’s a synopsis: For a young man (Godard) life is dark when he wears sunglasses. When he takes them off, things improve.

Figure 15. The Lovers of MacDonald Bridge with Jean-Luc Godard wearing sunglasses

‘Cléo from 5 to 7’ was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It provided the impetus for Agnès to write other films featuring women. Among them, ‘One Sings, the Other doesn’t,’ from 1977, about two women whose lives intersect before and after decisions each makes about men and children and careers. In 1985, ‘Vagabond' reveals, through a series flashbacks, the life of a woman found dead in a ditch in the French countryside. She had abandoned her quotidian life in Paris to wander around the countryside. Her life became increasingly difficult and finally she was too weak to get out of the ditch into which she had fallen and in which she died. The film won a Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for four César awards.

Not long after ‘Cléo from 5-7,’ Agnès was asked to take part in a fashion shoot for which Frank Horvat, about whom I have written, was the photographer. For an issue of Harper's Bazaar, she was one of four women selected to represent Parisian elegance. Each woman posed next to a model wearing haute couture. Rather than play into the idea, Agnès played against it. (Fig 16) She posed crouching, almost hidden by the model.

Figure 16. Agnès Varga crouching behind a model, Frank Horvat

Through the 1960s, Agnès made her living taking photographs for weddings, christenings and bar mitzvahs and of actors and artists. When she could, she photographed people who were down and out or sometimes just poor and mostly, well at least to everyone but Agnès, invisible. Based upon photographs she had taken a year earlier, her short film ‘L’Opéra-Mouffe’ (1958) centers on rue Mouffetard, not the charming street it is now, but as it was back then. According to one critic, her photos of the market establish a parallel between the food stalls and her round belly, “between a desperate population and the hope that comes with bringing a child into the world.” (Figs 17-19)

Figure 17. Opéra-Mouffe, rue Mouffetard, Paris, 1958

Figure 18. Opéra Mouffe, rue Mouffetard, Paris, 1958

Figure 19. Clochards (homeless men) 1958

Choosing the rue Mouffetard was not an anomaly. Picturesque Paris never tempted Agnès. In 1984, her short film, ‘Les Dites Cariatides,’ took as its subject, the caryatids that still adorn so many of the Haussmannian facades of buildings in Paris. Cleverly, she contrasts the caryatids, female figures who effortlessly support balconies, with their male counterparts, Atlantes, whose straining muscles show just how hard the same job is for them. According to one critic, in this film, Varda ’deconstructs gender in architecture.’ (Figs 20-22)

Figure 20. Angel on the facade of a building on rue Turbigo which Agnès Varda enlisted people to help clean, 1984

Figure 21. Les dites Cariatides, 1984

Figure 22. Straining Atlantes and elegant Caryatids on same facade, rue Montmartre, Paris

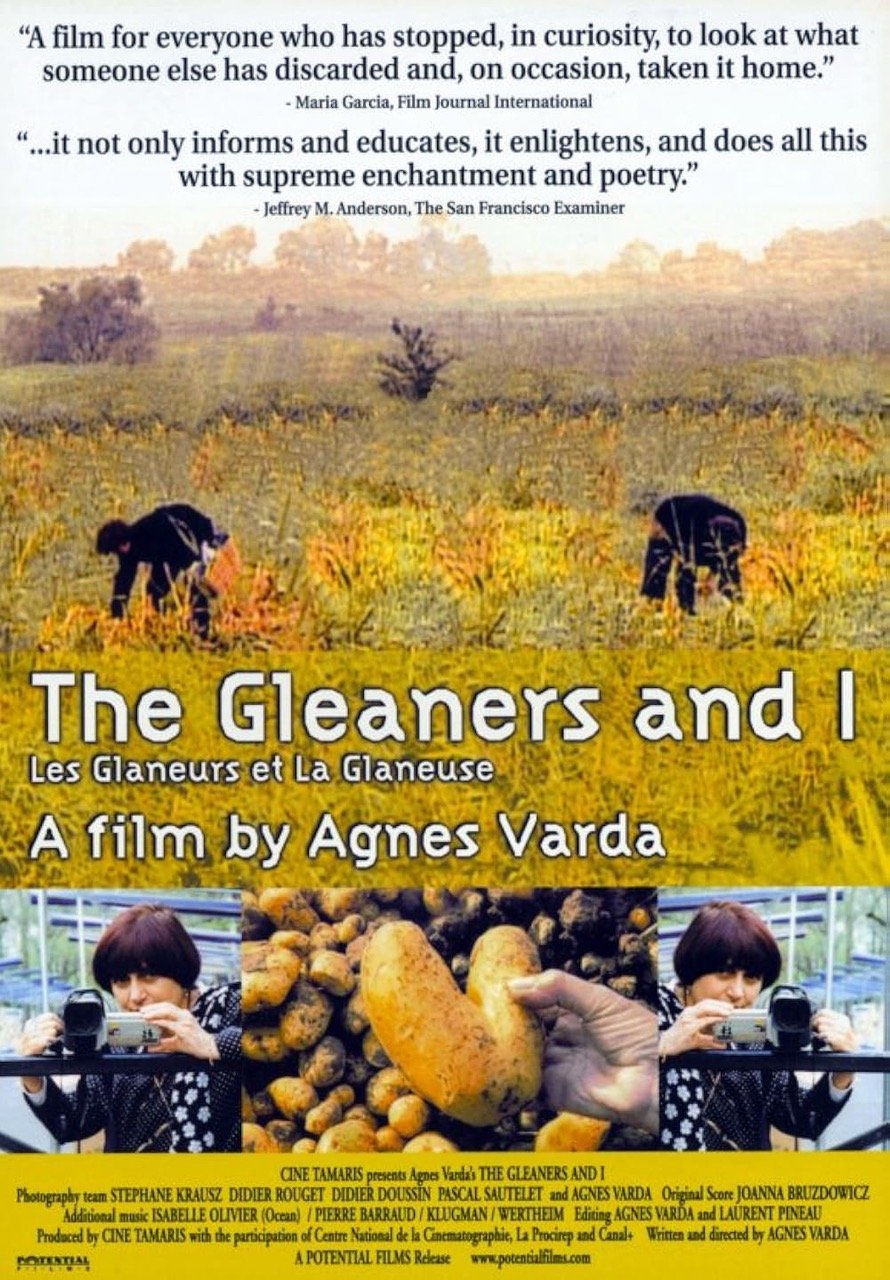

In 1999, when they were in China, her son showed her a digital camera. She used one for the first time in her 2000 film, ‘The Gleaners and I.’ The film is about the act of collecting what is left behind after the harvest. The focus is on potatoes gleaned from a newly dug-up field. She offers an historical context, juxtaposing her own footage with depiction by artists like Millet and van Gogh. She adds modern forms of gleaning, foraging (dumpster diving) in bins and crates, behind shops and on city streets, particularly after the marches close and before fruit and vegetables are cleared away. (Figs 23-27)

Figure 23. The Gleaners and I, with a few reviews above, 2000

Figure 24. Agnès Varda as Gleaner

Figure 25. Gleaners by Jules Breton

Figure 26. Chiffonier, Eugène Atget

Figure 27. Urban Gleaners, organizations fighting food waste and insecurity

In 2008, Varda created an “auto-documentary" film, ‘The Beaches of Agnès.’ In it she revisits places from her past, reminisces about life and celebrates her 80th birthday. True to the film’s title, she transformed her street into a beach by borrowing 72 tons of sand from the 2007 Paris Plage (the artificial beaches the City has installed along the banks of the Seine every summer since 2002). Although in the film she posits that this film will be her last, there were two more, ‘Faces/Places’ (2017) and ‘Varda by Agnes’ (2019). (Fig 28)

Figure 28. The Beaches of Agnès, 2008

In 2017, she and JR made the film ‘Faces/Places.’ It was a road trip through the French countryside. Over the course of their travels, the artists get to know each other and become friends. Despite both a generational gap and a cultural one, Varda’s daughter notes, "They spoke the same language; it was a bit like an old married couple, with a lot of teasing.” During the film, Varda talks about "Les fiancés du pont MacDonald", the short film she inserted in her 1961 film 'Cléo from 5 - 7.' Like JR, the young man in the film, played by Jean-Luc Godard, always wears dark glasses. Varda and JR decide visit Godard in Switzerland. When they get to his house, he refuses to see them. Varda begins to cry. To soothe her, JR takes off his own sunglasses. We see his face through her eyes, but she is losing her sight, his face is blurred. (Figs 29-32)

Figure 29. Faces / Places, Varda & JR

Figure 30. JR plastering blown-up photographs of people that he & Varda met who became Faces/Places

Figure 31. Agnès Varda & JR on Quotidian in 2017, talking about Faces / Places

Figure 32. Rosalie (Agnès’s daughter) Agnès (wearing Gucci) and JR at the Oscars

The last of Varda’s films, ‘Varda by Agnes’ was completed in 2019, just months before she died. In it Varda reflects on the things she loves, like cats and beaches and heart-shaped potatoes. And her husband, Jacques Demy, next to whom she is buried.

At age 89, after the success of her film ‘Faces/Places,’ she said: “I think I’m lucky because I didn’t lose the curiosity, the desire, the energy, and the need to express myself.” In her final film, Agnès picked out three words that had motivated her: inspiration, creation, and sharing. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Old Agnès thumbing her nose, young Agnès looking as if she is part of a procession of clerics. Agnès wore her hair this way her entire life, but it didn’t mean that she couldn’t have fun with it - she did!