Leaping Suddenly into Deep Waters

Today’s subject - two exhibitions - one on Henri Matisse’s paintings of his daughter, Marguerite and the other a retrospective of the artist, Gabriele Munter. I was assuming that Munter’s story would be more compelling because, well, really how interesting can the life of the daughter of a famous artist be, turns out very. Stay tuned.

In poking around the internet I discovered that, counting the exhibition I will be talking about today, over the past 30 years, there have been six major exhibitions about Gabriele Munter in W. Europe and N. America. At the fabulous museum outside Denmark, the Louisiana and at the magnificent Thyssen-Boernimsiza in Barcelona; at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, at the Milwaukee and Virginia Museums of Art, and coming in November 2025, an exhibition on Munter, will be held at the Guggenheim, in NYC.

So, even if Munter is not a household name, she is not unknown. The exhibition I saw was at MAM, the abbreviation for the Musée d’Arte Moderne de Paris. Not to be confused with the Centre Pompidou, the more famous modern art museum in Paris. MAM is hoping that its name will become as easily recognizable as that other modern art museum which goes by its initials, MoMA. People love acronyms so maybe it will work.

The first thing I thought when I entered the exhibition was why wasn’t Münter, a German Expressionist, in the Degenerate Art exhibition at the Musée Picasso. I hoped that the exhibition would explain how Münter escaped the wrath of the Nazis. It did.

You may have heard of Gabriele Münter as one of the women associated with German Expressionism or as a footnote in a discussion of her lover, Wassily Kandinsky. (Figs 1, 2) The justification for an exhibition on Munter at MAM has nothing to do with Kandinsky, it is because she fits within “MAM’s policy of presenting major female figures in modern art with close ties to France's capital.” And she did. Münter began her career in Paris in the early 1900s, exhibited her work for the first time in Paris (in 1907), and spent considerable time here between the wars and afterwards, too. (Fig 3)

Figure 1. Portrait of Wassily Kandinsky by Gabriele Münter, Linotype, 1906

Figure 2. Portrait of Gabriele Münter, Wassily Kandinsky, 1905

Figure 3. St Cloud, Gabriele Münter, drawing, 1906

I thought it would be interesting to read what Roberta Smith (NYT art critic) wrote about the first of the exhibitions I found, the one held in 1998 at the Milwaukee Museum of Art. Why, I wondered was an exhibition about Munter held at that museum and why then. Turns out, Milwaukee has more paintings by Munter than any museum outside of Germany. And the exhibition was timed to coincide with the publication of a book about Munter written by R Heller, curator of the exhibition and Prof at U of Chicago. (Fig 4)

Figure 4. Boating, Gabriele Münter. Kandinsky stands, Münter rows, 1910 (Milwaukee Museum of Art)

I read Roberta Smith’s review of that exhibition. I was particularly interested to see if or how the rhetoric about female artists has changed in the past quarter century. Smith’s article, called “ART; Lost in the Glow of the Man at Her Side,” begins with a list of artist couples. The well known male artist and his lesser known (sometimes unknown) female companion. The man inevitably celebrated as the genius, the woman as his inferior helpmeet. Throughout the article there are (I’m going to say, well deserved) digs about Kandinsky who was as misogynistic as Picasso, except with fewer victims. From 1904 until about 1917, Munter and Kandinsky were a couple. So it would be difficult to write about Munter without mentioning Kandinsky. Except would it? Lots of people have heard of Kandinsky, but how many of them know about the role, artistic and personal, that Munter played in his life? So maybe the lament is really about how the female half of artist couples is perceived and described by critics. (Figs 5, 6)

Figure 5. Interior at Murnau. 1910, recalls Van Gogh's painting of his bedroom. Münter’s stuff and Kandinsky’s, litter the floor. Their work hangs on the walls, they painted the furniture. He is in bed in the left hand corner.

Figure 6. The room Münter might have been thinking about when she painted her room (see above Fig. 5), Van Gogh

Ten years later, Cody Delistraty (Paris Review) begins his review of the Munter exhibition at the Louisiana Museum this way, “.. Before you’re able to focus on her aesthetic breakthroughs—on the way in which she positioned and profiled and photographed women…social conditioning dictates that you look first at the shadow of her long-term lover, the better-known Wassily Kandinsky. History, of course, tends to take for granted that women have been influenced by the men in their lives while the very same men aren’t seen as having been influenced by these women. Viewing art has tended toward the same effect: lonely men are “lone geniuses” while lonely women, those who devote themselves to their art at the expense of love or family, are ‘art monsters.’”

As Delistraty notes and the curator of the Louisiana Museum confirms, “The idea behind the career-spanning exhibition of Gabriele Münter at the Louisiana (was) to … break her free from Kandinsky” “by unfolding and opening up new aspects of her many-faceted work, …to highlight its stylistic complexity and artistic independence….”

Likewise, in the exhibition at MAM, Kandinsky is mentioned but he isn’t the focus. He appears in her life but he doesn’t define her work. So, while these museum exhibitions try to get beyond Kandinsky, it’s the reviewers who can’t, or don’t, or won’t.

Let’s start this review where MAM does, before Munter met Kandinsky. Munter was born in 1877, in Berlin, into an upper-middle class family. Drawing came naturally to her and her parents encouraged her inclinations with private tutors. She was 9 when her father died, 20 when her mother died. In 1898, Gabriele and her sister Emmy found themselves alone in the world, with a lot of money and nothing to do. Road Trip!

At the invitation of relatives living in the United States, the Munter sisters packed their bags and left for America. They stayed for 2 years. Where they went wouldn’t have been my choice and maybe wasn’t theirs, either. But it was where their family lived - Texas, Arkansas and Missouri. Munter filled 6 sketchbooks with drawings of people and places. And from February 1900 until they returned to Germany, she took hundreds of photos with a Kodak camera she bought in Abilene, Texas. It was lightweight and portable, ideal for capturing scenes from everyday life.

Through the camera’s lens, Münter explored photography’s possibilities. Subjects that would reappear in her paintings and prints - landscapes, children, people working, people at leisure, portraits. Among her photographs are several documenting the Juneteenth festivities of 1900. June 19th is the date in 1865 that African Americans were emancipated. The date was celebrated in the 19th century, mostly forgotten in the 20th and established as a national holiday in 2021. Will it be celebrated this year? Another photograph shows a woman with an umbrella in the countryside, reminiscent of Monet. And another of a young woman reading that echoes Fragonard’s La Liseuse. (Figs 7-12)

Figure 7. Kodak Camera like the one that Gabriele Münter bought in Abilene, Texas, 1900

Figure 8. Juneteenth celebration, Gabriele Münter, June 19, 1900

Figure 9. Woman with an Umbrella, along the Mississippi in St. Louis, Missouri, 1900

Figure 10. Madame Monet and son, Claude Monet, 1875

Figure 11, The Reader, Gabriele Münter, 1900

Figure 12, The Young Reader, Jean-Honore Fragonard, 1769

When the Munter sisters returned from their travels, Gabriele resumed her art studies. She went to Munich, where, because women were not permitted to take art classes with men, her choice was to either go to a ‘ladies art academy,’ or take private classes taught by male artists. Then she discovered the Phalanx School, founded by a group of artists opposed to traditional, conservative art practices. This experimental, short-lived school did permit women to take classes alongside men. The founding members of Phalanx included Wassily Kandinsky from whom Munter took drawing classes. Münter fell in love with his mind before she fell in love with him. Kandinsky, unlike her previous instructors, took her seriously. He, she said, "regarded me as a consciously striving human being." Which must have been a strong aphrodisiac for a serious young artist. He asked her to join him for a summer painting program in the Alps and she agreed.

Their relationship was tumultuous and fraught. He was her teacher, he was 11 years her senior, he was married. But he promised to divorce his wife and so she became his mistress. Sometimes telling people they were engaged, sometimes using his surname to sign her paintings. It must have been difficult for a young woman of her background to find herself the ‘kept woman’ of a married man. Maybe even worse for a serious young artist to find herself in that predicament.

And yet, among Munter’s recollections are these. “At first I experienced great difficulty with my brushwork… So Kandinsky taught me how to achieve the effects that I wanted with a palette knife... My main difficulty was I could not paint fast enough.… When I begin to paint, it's like leaping suddenly into deep waters, and I never know beforehand whether I will be able to swim. Well, it was Kandinsky who taught me the technique of swimming. I mean that he has taught me to work fast enough, and with enough self-assurance, to be able to achieve this kind of rapid and spontaneous recording of moments of life.”

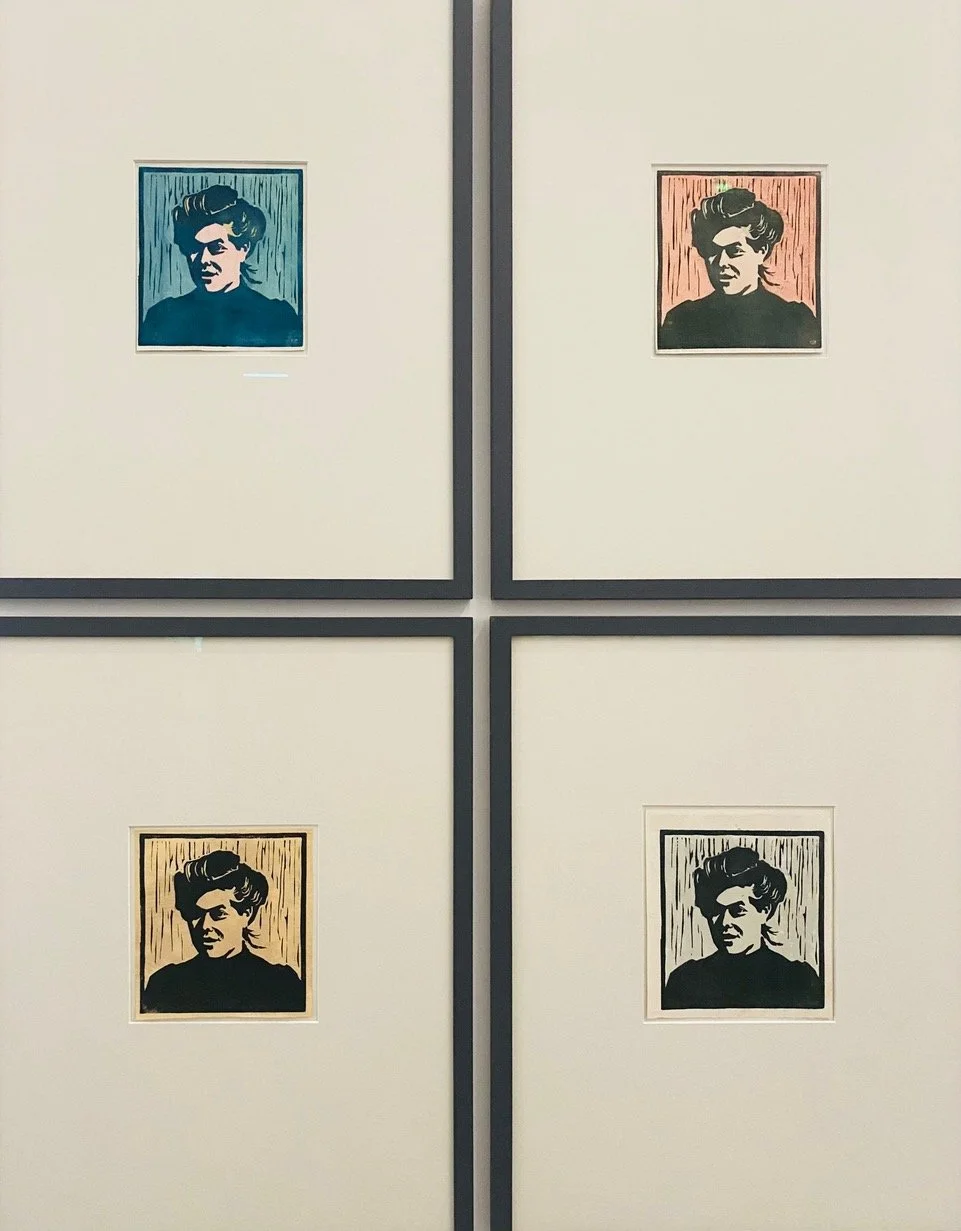

Munter and Kandinsky traveled extensively. On one trip they went from Holland to Italy to Tunisia. The first time they traveled to Paris was 1906. They returned the following year in May and stayed for 14 months. When Kandinsky left for a few months at the end of 1906, Munter rented a room in the same building in which Gertrude Stein’s brother Michael and his wife Sarah, collectors of Matisse, lived. One of the engravings Münter made while there, is a portrait of her landlady, Mrs Vernot. In the background, Mme Vernot’s maid, Aurelie, works in the kitchen. Münter also learned linocutting in Paris. It’s a technique derived from woodcutting which has the advantages of spontaneity and simplicity. Münter composed some linotypes as different colored series, like the four portraits of Aurélie, each a different color, each perhaps a different sensibility.(Figs 13, 14)

Figure 13. Portrait of Mme Vernot with Aurelie working in the background, Gabriele Münter, engraving, Paris, 1906

Figure 14. Aurelie in four different colored backgrounds, Gabriele Münter, Linotype, Paris, 1906

At the Salon des Indépendants in 1907, Münter exhibited six paintings and six engravings. One painting is a winter view from her window in Sevres, a suburb of Paris. A tree with naked branches stands in the middle ground, stopping the viewer from entering and simultaneously leading the viewer’s eye into the scene. (Fig 15)

Figure 15. Scene from window in Sevres, Gabriele Münter, Paris 1906

In 1908, Münter returned to Munich. She painted portraits of her friends and neighbors. Among them is a portrait of her landlord and a portrait of her neighbor’s son. In these portraits we can detect a French Fauvist influence in the colors she uses, vibrant and independent of factual representation. Her work resonated with her German contemporaries who were looking to convey feelings rather than facts. (Figs 16, 17)

Figure 16. Mr. Miller, the landlord, Gabriele Münter, Munich, 1908

Figure 17. Willi Blab, neighbor’s son, Gabriele Münter, Munich, 19098

That summer, Munter spent time in Murnau, a village an hour by train from Munich. Descriptions of Murnau and Munter’s paintings of the village, remind me of Burano, the island off Venice where the flat facades of the houses are all painted different colors. It was a particularly good place for Munter as she continued to follow the French Fauves playbook, separating color from context. (Figs 18-19)

Figure 18. A Street in Murnau, Gabriele Münter, Murnau, 1908

Figure 19. A street in Burano, Italy

When Munter bought a house in Murnau, she and Kandinsky mostly lived there, although they remained active members of Munich’s art scene. In 1911, they were founding members of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) along with Franz Marc, August Macke and Paul Klee, Both Münter and Kandinsky participated in that group’s exhibitions and the publication of its Almanac, a theoretical work that laid the foundations of an international, multidisciplinary avant-garde.

One key element of Munter’s work separates her from her fellow German Expressionists. The absence of angst. The people she portrays aren’t worried or nervous, her landscapes aren’t threatening, there is no sense of foreboding. For her, Fauvism didn’t lead to social satire (Kirchner) or intellectual rumination (Kandinsky). As Smith notes, Munter, like Matisse “painted for the sake of painting, for the pleasure of recording her perceptions of the visible world in such a way that the colors and forms on the canvas took precedence, but without obliterating that world.” (Figs. 20-24)

Figure 20. Listening (Portrait of Jawlensky), Gabriele Münter, 1909. This artist's work was condemned as degenerate because he continued to paint after he began suffering from crippling arthritis. To the Nazis, his work was a bad example, it had to be censored.

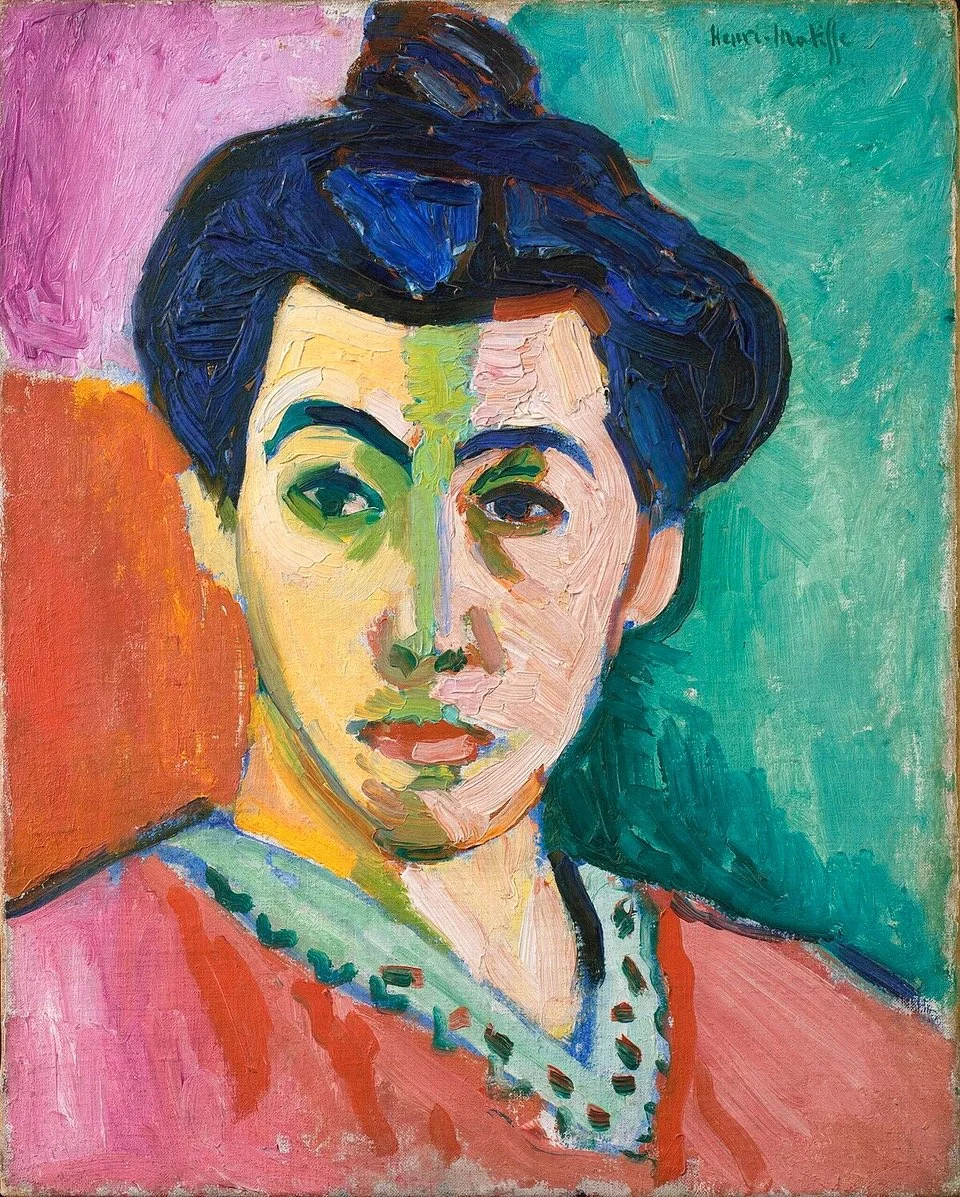

Figure 21. Marianna von Werefkin, Woman in Hat. 1909; She was the companion of Jawlensky (Fig 20). She stands in front of Munter’s house in Murnau. This painting recalls Matisse’s painting The Green Stripe from 1905 which Munter may have seen in Gertrude’s Stein’s house

Figure 22. Mme Matisse, Henri Matisse, 1905

Figure 23. Portrait of a young girl, Gabriele Münter, 1908

Figure 24. Marguerite, Henri Matisse, 1906

In 1915 Munter and Kandinsky moved to Scandinavia. He soon left for Russia where he stayed until the end of the Great War. While he was there, Kandinsky finally obtained a divorce. But wouldn’t you know it, he married another woman. Munter only learned of his betrayal when he sent a lawyer around to her house to collect his paintings.

How difficult it must have been after all those years of being Kandinsky’s mistress to learn that she would never be his wife. (Figs 25, 26) For a while she didn’t paint and then in 1927, she met Johannes Eichner, an art historian 9 years her junior. They married and while they both knew that Kandinsky had been the great love of her life, theirs was a partnership that endured until his death, four years before her own.

Figure 25. The Thinker (Gertrude Holz) 1917. Münter painted this woman’s portrait several times when she was in Stockholm. This work was exhibited in 1918 in Copenhagen, during the largest solo exhibition of her work held during her lifetime.

Figure 26. Stenographer, 1929, Dressed in fashionable light trousers, taking notes. Without any contextualization, the focal point is the act of writing itself. More symbol than portrait. Here Münter bears witness to the emancipation of women through work. The "new woman" (Neue Frau) in Germany, the flapper in America and the garçonne in France.

By 1931, Münter was living permanently in Murnau, although she continued to make trips, within Germany and to Paris. (Figs 27-32) She kept painting but at her husband’s urging, she kept a low profile. What about the question I asked at the outset of this piece. What did Munter do during the war? Where was she when Nazis ransacked museums looking for degenerate art, when they were condemning degenerate artists? Well, luckily for her, I suppose, her paintings weren’t in any art museums so they weren’t dragged off any museum walls and she wasn’t condemned. But she did hide her own paintings and those by Kandinsky and other members of the Blue Rider in the basement of her Murnau house. Although the house was searched several times and hiding them involved considerable risk, the Nazis never found them. In 1957, on her 80th birthday, Münter donated them to the Lenbachhaus in Munich. Below some beautiful paintings by Munter, from the 1930s until nearly the end of her life. Enjoy!

Figure 27. Breakfast with the Birds, 1934. Murnau. Symbolic self-portrait as she was turning 60. The viewer can identify with the figure represented from behind, as if they were sitting at table and like her, watching the birds in the trees of the garden through the window of her house.

Figure 28. The Letter, Gabriele Münter, 1930. The bedridden model is Lou Albert-Lasard

Figure 29. Still life with red serving spoons, Gabriele Münter, 1930. Münter painted this still life during her second stay in Paris. The close-up view of this corner of the table is reminiscent of a photographic zoom.

Figure 30. Scaffolding, Gabriele Münter, 1930

Figure 31. Principle Street, Murnau, Gabriele Münter, 1936

Figure 32. Blue Lake, Gabriele Munter, 1954

Matisse and his daughter, Marguerite

Once again, I’ve run out of space, I’ll tell you about Marguerite next time, about, among other things, why she wore a ribbon around her neck for 15 years (no, it has nothing to do with Edgar Allan Poe’s short story of the Velvet Ribbon) and why she sent her only son, her only child, to America in 1940. I’ll tell you about how brave she was and finally how tirelessly she worked to preserve and protect her father’s legacy. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

For further reading about Gabriele Münter, you can start with these three articles:

Cody Delistraty, When Female Artists Stop Being Seen as Muses, July 2018, The Paris Review https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/07/06/when-female-artists-stop-being-seen-as-muses/ (about exhibition at the Louisiana Museum, Denmark)

Anna McNay, Painting to the Point, Studio International, 26/12/2018 .https://www.studiointernational.com/gabriele-munter-painting-to-the-point-review-museum-ludwig-cologne (about exhibition at Museum Ludwig, Cologne)

https://www.museothyssen.org/en/exhibitions/gabriele-munter

Roberta Smith, ART; Lost in the Glow of the Man at Her Side, New York Times, Aug. 1998. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/08/16/arts/art-lost-in-the-glow-of-the-man-at-her-side.html