Matisse and Marguerite: Through Her Father’s Eyes

This is the second, maybe the first, well anyhow, the other exhibition currently at MAM. A friend who saw the exhibition before I did told me he thought it was a bit ‘thin.’ I don’t agree. Especially if you come to it, as I did, as many of us do, with at least a few of Matisse’s portraits of his daughter swimming around in our heads. Besides being a feast for the eyes (which Matisse’s paintings, sculptures and cut-outs are for me), the exhibition explains why Matisse depicted his daughter Marguerite so often.

There are more than 110 works - paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures and ceramics – by Matisse in this exhibition, nearly all feature Marguerite. At the end, a video of archival photographs traces Marguerite's life alongside her father's. As one of the curators noted, “We think we know all there is to know about Matisse, but here we have an image of him that is completely unknown to the public.”

The first thing we learn is that Marguerite was Henri Matisse’s daughter, but she was not Matisse’s wife’s daughter. Matisse fathered Marguerite in 1894, soon after he moved to Paris to study painting. Her mother was Caroline Joblaud, a model. They were together for a few years but never married. When Marguerite was 2, Matisse officially recognized her. By the time she was 4, Matisse was married to Amélie Parayre. Who offered to raise Marguerite as her own. Marguerite got on well with her adoptive mother and her two half brothers, Jean and Pierre. "We are like the five fingers of one hand," was how she once described her close-knit family. (Fig 1)

Figure 1. Matisse Family, 1911, Marguerite between her 2 half-brothers. Painting behind, ‘Large Nude’

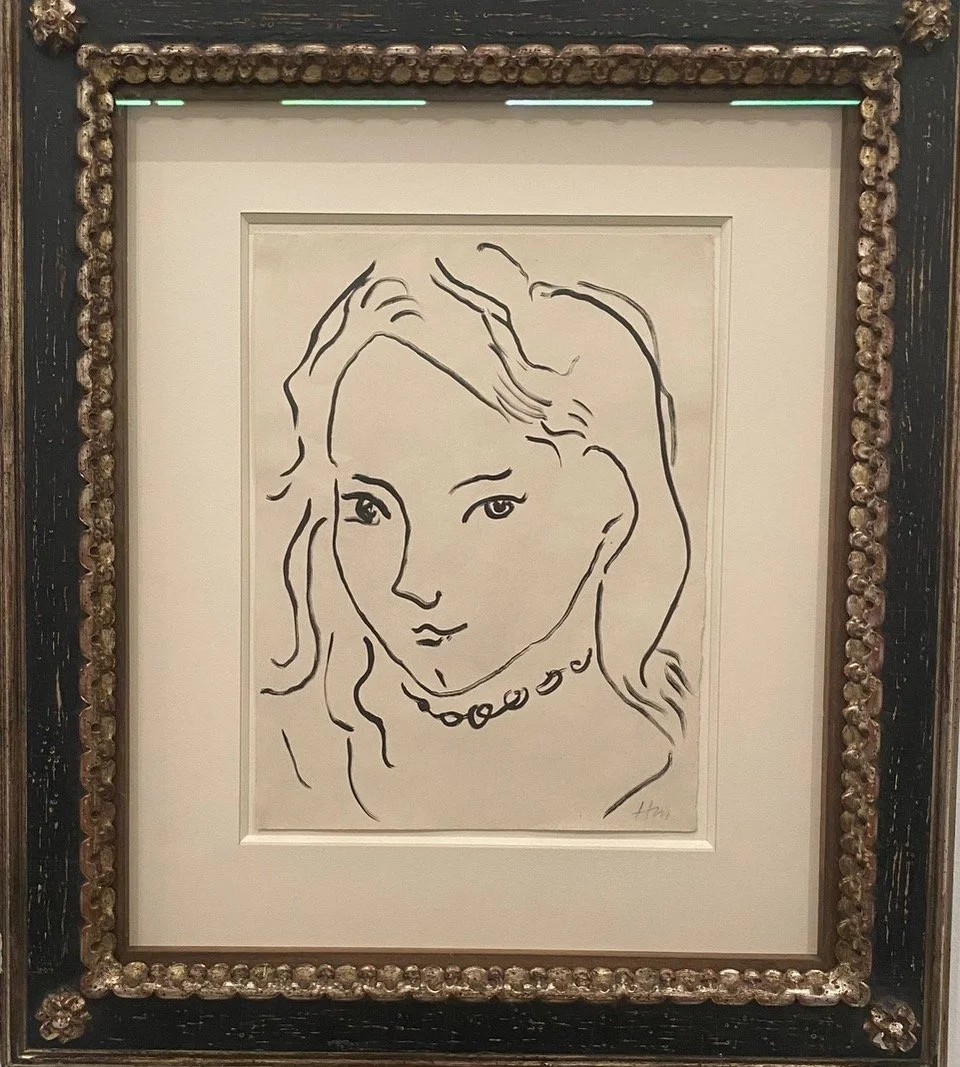

Matisse depicted Marguerite more than any other model. He depicted her alone as she grew up and with other, professional models, when she was older. ‘She was essential to Matisse’s work,’ according to Charlotte Barat-Mabille, one of the three co-curators of the exhibition but ‘nobody really knows anything about her.’ (Fig 2).

Figure 2 Marguerite, Matisse, black ink on paper, 1906-07

Have you noticed that in Matisse’s portraits of Marguerite, she has a ribbon around her neck? I used to think of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, The Velvet Ribbon, each time I saw one of those portraits. But now I know why she wore that ribbon. In 1901, when Marguerite was 7, she caught diphtheria. Diphtheria, according to the Institut Pasteur, “typically manifests as a respiratory infection that causes impairment of the central nervous system, the throat and other organs…” People in the United States and Western Europe don’t get diphtheria now because children are vaccinated against it. Diphtheria is still common in developing countries and will become common again in the United States if the current Secretary of Health and Human Services and anti-vaccine activist, gets his way. In the past, a large number of people died from diphtheria in the U.S. and it may become a convenient way of culling the population once again.

Marguerite didn’t wear the ribbon around her neck because of the diphtheria but because of what happened afterwards. One day, all of the sudden, she couldn’t breathe, she started to suffocate. With her father holding her down on the kitchen table, an emergency tracheotomy was performed. The operation left a scar on Marguerite’s neck. Which she always hid - sometimes under a high collared blouse or dress and sometimes with a black ribbon. In Matisse’s portraits of her, it is the ribbon especially, that became her attribute, occasionally embellished with a sparkling pendentif. (Fig 3) So there she was, with a damaged larynx and a scar on her throat, constant infections and chronic fatigue. She was too sickly to go to school. But she did have a stay at home dad in whose studio she could hang out.

Figure 3. Marguerite in blue polka dot dress and elegant green hat, Matisse, 1906

Matisse depicted Marguerite reading or writing or just looking right back at her father and us. Marguerite’s visage can be found in all of her father’s color and compositional experiments. The 1905 painting ‘Intérieur à la fillette’ depicts Marguerite (age 11) sitting on a chair, at a table. (Fig 4) One hand holds up her forehead, the other holds down the page of the book she is reading, (which is propped up by a larger volume). While she calmly concentrates on her book, a riot of colors swirls around her - identifying her person and the objects and space that surrounds her.

Figure 4. Intérieur à la fillette, Matisse, 1905

The painting caused a scandal at the 1905 Salon d'Automne. The critic Louis Vauxcelles disparaged Matisse’s paintings and those of the artist Derain, calling both artists fauves (wild beasts). And just like that the name of an art movement was born - Fauvism. Fauvist paintings can be identified by wild brush strokes and strong, sometimes strident colors. Fauves simplified and abstracted their subject matter in contrast to the more representational canvases of their impressionist predecessors. Fauvism as a style began in 1904 and lasted through 1908. BTW - Vauxcelles also gave another art movement its name - Cubism. That wasn’t meant as a compliment either.

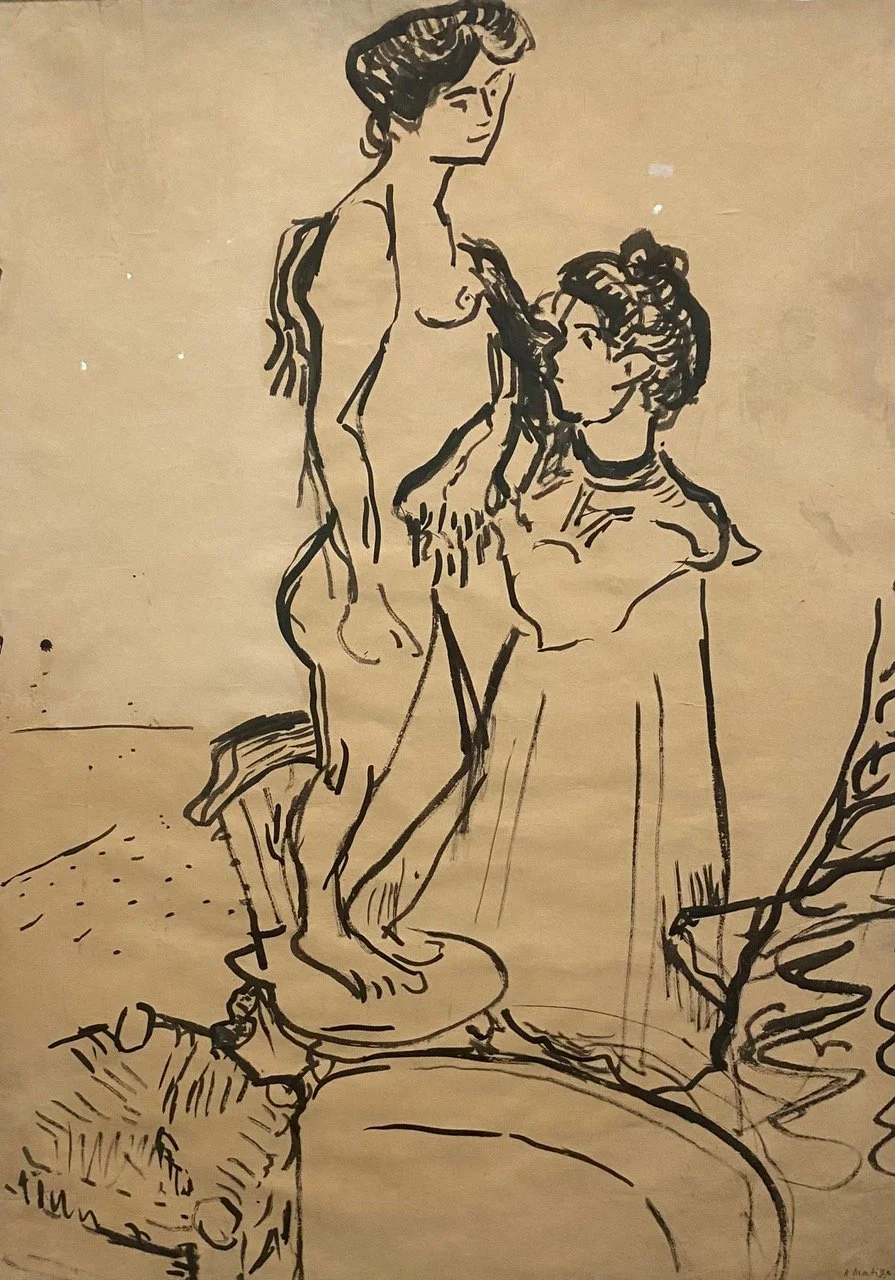

There’s another work, an ink drawing called La Toilette, (Fig 5) from 1905-06 which shows just how comfortable Marguerite was with traditional studio practice. In this drawing, we see Marguerite (black ribbon around her neck) handing a towel to a nude model who stands on a chair near the tub in which she has just bathed. Like other artists, Matisse drew and painted nudes from live models. The close proximity of the two figures suggests that Marguerite was at ease with this very common studio practice.

Figure 5. La Toilette, black ink drawing, Matisse, 1905-06

In the summer of 1906, the Matisse family traveled to Collioure (where Matisse had been the year before and where he would return in years to come) a modest fishing village located on the Mediterranean coast. It was in Collioure that Matisse made his first major series of works featuring Marguerite. Then twelve years old, Marguerite was everywhere in her father’s work - paintings, drawings, sculpture, even a ceramic plate. (Fig 6) In one painting, Marguerite looks straight ahead. At the top of the canvas, Matisse wrote Marguerite’s name, in script that imitates a child’s handwriting. (Fig 7) A “thick black line defines the figure and frames the whole composition.” While some of Matisse’s contemporaries “made fun of its rudimentary and naive appearance,” the painting “fascinated Picasso, who traded it for a Cubist still life and kept it until the end of his life.”

Figure 6. Marguerite with a rose, Matisse, 1906

Figure 7. Marguerite, 1906/07, Matisse

Another painting, ‘Marguerite lisant,’ (Fig 8) which Matisse exhibited at the Salon d'Automne of 1906, became “one of Matisse's most emblematic paintings.” It seems a distillation of the painting of Marguerite Reading from the previous year. Marguerite has grown up a bit and her father has eliminated all the extraneous elements of the earlier painting. But here, Matisse’s approach has changed. “The fragmented brushstrokes have given way to a calmer, more collected technique.”

Figure 8. Marguerite lisant, Matisse 1906 - her blue polka dot dress in Fig. 3 has become red polka dot here

Matisse painted ‘Marguerite au chat noir’ in 1910. (Fig 9) He must have been very happy about it because he exhibited it at the Berlin Secession Exhibition in 1910, the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London in 1912, and in all three venues of the famous Armory Show in 1913 (New York, Chicago, and Boston).

Figure 9. Marguerite au chat noir, Matisse, 1910

There was one painting that I was relieved not to find here. It wasn’t even alluded to, thank goodness. The painting, from 1911, is a full length reclining nude which art historian and brother of Adam, Blake Gopnik contends is Marguerite. (Fig 10) She was 17 years old in 1911. As you can see, she isn’t wearing anything, not even the tell-tale ribbon around her neck. But daisies, (marguerites in French) swirl around the nude’s body. The painting is prominently displayed in another painting by Matisse, also from 1911, The Red Studio. (Fig. 11 about which I have written here: (Red Hot Matisse) The Red Studio was intended as a companion piece to a third painting from 1911. Of Matisse’s family. (Fig 12) In this painting, Marguerite sits on a sofa, a black ribbon around her neck and wearing a dress covered with daisies. The Red Studio and The Painter’s Family were intended for Matisse’s most important patron, the Russian businessman and art collector, Sergei Shchukin. He bought the Painter’s Family (it’s now at the Hermitage) but refused The Red Studio (which is now at MoMA).

Figure 10. Photo of Large Nude (which is behind Matisse family in Fig. 1) Matisse, 1911, now destroyed

Figure 11. The Red Studio, Matisse, 1911 (Large Nude on left)

Figure 12. Painter’s Family (girl on sofa at left is Marguerite wearing a dress decorated with daisies) Matisse 1911

Gopnik suggests that what might have troubled Shchukin about The Red Studio was the placement of the chair on the right side of the canvas, directly opposite the painting of the nude. Placed just so the businessman could sit and stare at the nude body (of Marguerite?) as long as he wished. The Large Nude (FIg. 10) was destroyed by Matisse’s family after his death. Why did the family destroy the painting? Marguerite, according to Gopnik, claimed that her father did not consider the painting finished. But, again according to Gopnik, records show that Matisse tried to sell it more than once. And the family happily posed in front of it (Fig 1). Claiming that they destroyed the painting because it wasn’t finished is not credible. Lots of unfinished paintings survive, along with drawings and sketches. So, we still don’t know who the nude was or why the painting was destroyed.

In late 1912, Marguerite left for Corsica, hoping to study for a teacher’s certificate with her aunt, her step-mother’s sister, who directed a Teachers' College. It was too challenging and after a little more than a year, Marguerite returned to her parents’ home. It was a new home and studio in Issy-les-Moulineaux, the purchase of which was made possible by the support of Matisse’s Russian patron, Sergei Shchukin.

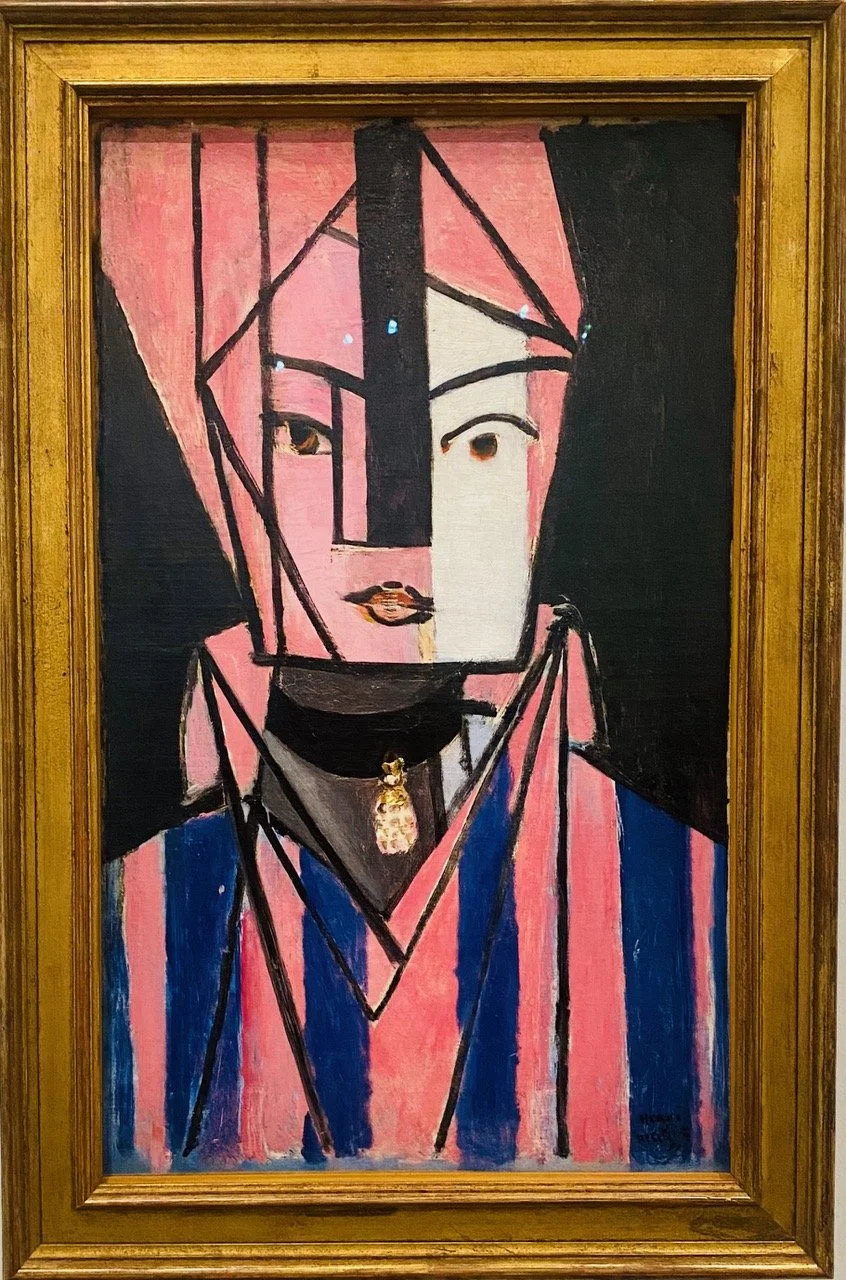

One of the portraits for which Marguerite sat when she returned, was ‘White and Pink Head’. (Fig 13) This is Matisse’s foray into Cubism. Marguerite's head is a rectangle, within a series of overlapping black lines. Her nose is a solid black rectangle that starts at the tip of her head. Half of her face is white, perhaps suggesting sunlight. Her striped hat is pink and the black stripes on her pink jacket are independent of the black stripes that extend from the jacket’s collar. The black ribbon is still there and so is the pendant.

Figure 13. White and Pink Head, Matisse, 1914

In early 1918, Marguerite visited her father in Nice. She posed on the balcony, in a fabulous plaid coat by Paul Poiret. Her hands in her lap, her book on her knees, her gaze far off. The thin bars of the balustrade open onto the blue Mediterranean Sea. (Fig 14)

Figure 14. Marguerite in Nice, Matisse, 1918

Back in Paris that autumn, Matisse riffed on his portraits of Marguerite in Nice. In one, her pose is similar to the balcony portrait and she wears the same hat. (Fig 15) A gorgeous brown wool and fur coat envelops her but virtually all other details have disappeared. In 1920, a Japanese museum wanted to buy it but Matisse hesitated. Marguerite convinced her father to sell the painting: "I'm asking you to think it over but not let yourself get caught up in the question of feelings, for example, not wanting to sell it because it's my portrait. [...] You'll be able to work with me again and it's more important for you to be represented in a museum.” He did, it’s still in Japan.

Figure 15. Marguerite, Matisse, 1918

In the summer 1919, Marguerite sat for a monumental painting in the garden at Issy-les-Moulineaux. Called Le Thé, (Fig 16) it’s the first time Matisse paired Marguerite with another female model. Marguerite turns her head towards us. She shares the foreground with her dog, Lili. Marguerite’s face, flattened and geometric, recalls Matisse’s earlier experiment with Cubism. The cat, barely visible on Marguerite’s lap, reminds us of the 1910 painting of Marguerite with a Black Cat.

Figure 16. Le Thé, Matisse, 1919

It wasn’t until 1920, 19 years after her emergency tracheotomy that the hole in Marguerite’s neck finally healed. The medical advances that led to Marguerite’s successful treatment was probably the only good thing that came out of WW I. All those wounded soldiers needing all that medical intervention led to breakthroughs that civilian populations eventually benefited from. Matisse’s portraits of Marguerite in Étratat (Normandy) show an exhausted convalescent. (Figs 17, 18) But, finally, she could take off the ribbon and choose a dress that didn’t have a high collar.

Figure 17. Marguerite Asleep, 1920, Matisse - Marguerite sleeps after operation, we see her neck uncovered

Figure 18. Marguerite at Etretat (as above) relaxing after her operation, Matisse 1920

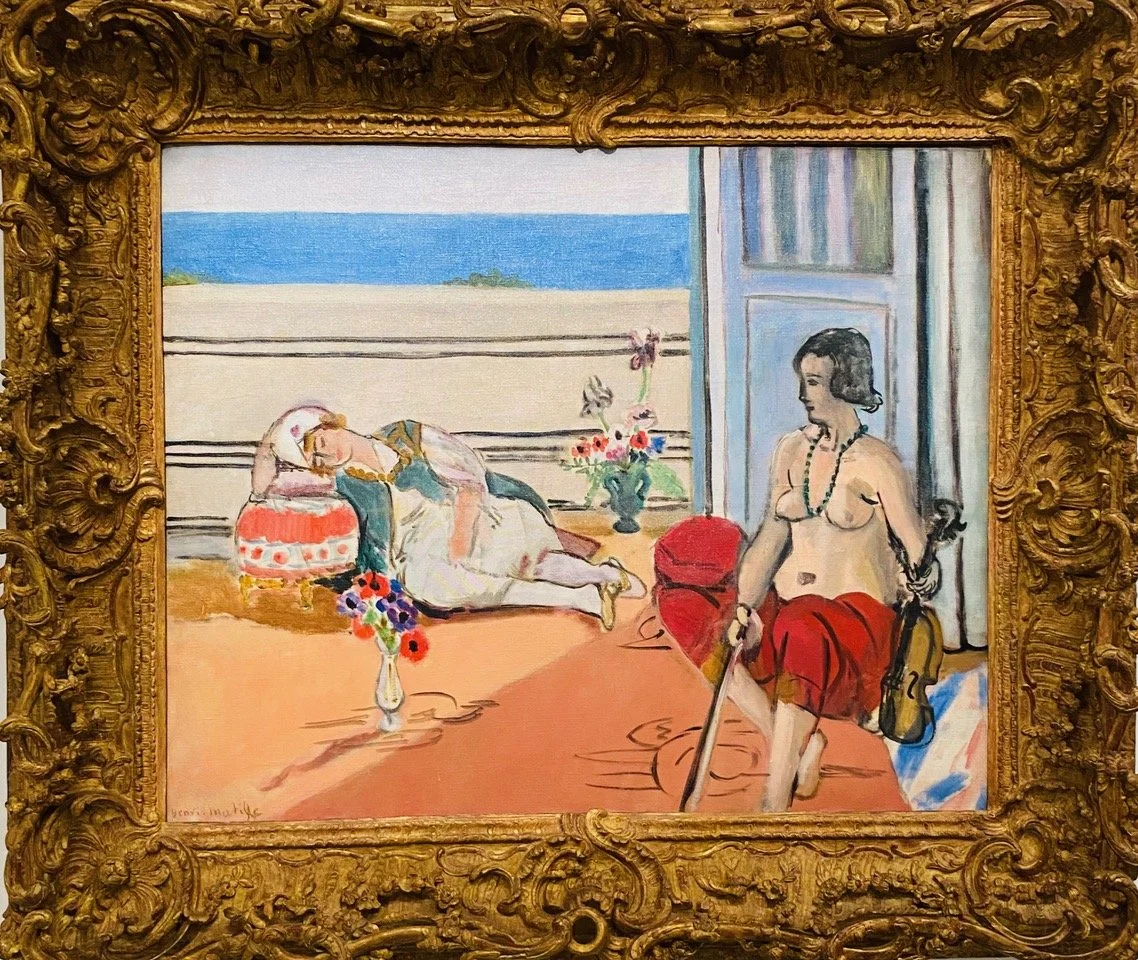

Marguerite continued to pose for her father in the early 1920s, although now always accompanied by another model. And something else has changed, too. Like Thé, the paintings are no longer portraits. And without her black ribbon, we can only identify Marguerite by her hair, which is lighter than the model her father paired her with. The women pose indoors and seem to be having fun playing dress up, wearing costumes in spaces filled with sumptuous fabrics and colors. (Figs 19-21)

Figure 19. Le Boudoir, Matisse, 1921

Figure 20. The Balcony, Matisse, 1921 - Marguerite rests her head against the poof

Figure 21. The Moorish screen, Matisse, 1921

They pose outdoors, too, on the balcony of the Hotel de la Méditerranée. (Figs 22, 23) Matisse shows the two young women enjoying their bird’s eye view of the Festival of Flowers, a grand parade of flower-covered floats, introduced during the Belle Epoque. In both paintings, the elegantly dressed young women observe the activities on the Promenade des Anglais beneath them

Figure 22. Festival of Flowers, Matisse, 1921

Figure 23. Fete des Fleurs, Matisse, 1921 - which one is Marguerite? Both have light hair

In 1923, Marguerite married the writer and art critic Georges Duthuit. She stopped posing for her father but she continued to play a role in his career. She acted as intermediary between him, now separated from his wife and living in Nice, and the collectors, historians, curators and art dealers who contacted him. She supervised the printing of his engravings in Paris. She oversaw exhibitions in Berlin and London. And with her husband, she began the catalogue raisonné of his work.

I had assumed that except for that horrific illness from which she suffered from the age of 7 to 27, that Marguerite’s life had been a comfortable one. Then I read that in 1940, she sent her only son Claude to New York to be with relatives during the war. Why would she do that I wondered, why would he have been in harm's way anymore than she or her husband. Then I read that when her son was safely out of the country, and when she was nearly 50 years old, Marguerite joined the French Resistance. She became a liaison agent for the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP) stating that "we cannot nor should we lose interest in the era in which we are living —in those who are suffering, who are dying." An informant identified her. She was arrested and tortured by the Gestapo, imprisoned and deported to Germany. Miraculously, she was freed in Switzerland just before reaching the German border. Matisse was in Vence and ill. He knew nothing of Marguerite's bravery and suffering. They were finally reunited in January 1945. Matisse drew two portraits of her. (Fig 24) There were to be no more.

Figure 24. Marguerite at Vence, 1945

The last room of the exhibition includes examples of Marguerite’s own forays into painting and fashion. Perhaps it proved too overwhelming to be an artist or a couturier if your father’s name was Henri Matisse. Or perhaps running his ‘shop’ while he was alive and protecting his legacy when he was not, was more than enough for a full life. Here are a few examples of Marguerite’s work. (Figs 25-27) Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 25. Self-Portrait, Marguerite Matisse, 1915 - the pendant on her cord she always wore

Figure 26. Amelie in the Garden, Marguerite Matisse, 1916

Figure 27. Dress designed by Marguerite Matisse, 1935

Thanks to those of you who have taken the time to send Comments, they are truly appreciated.

New comment on “Modern art on trial under the Nazis”:

I love your take on Musk--what disgusting excuse for a human being, so much like Trump. Keep up the good work, there is so much to be told, and your words should fall on many American ears. Vincent

New comment on Gabriele Münter: Leaping Suddenly into Deep Waters:

Thank you, Beverly, I really enjoyed reading this! I have become very interested in the stories of female artists of the past, or lack of their stories. This was a wonderful presentation of one of them! Sydney, Portland, OR

Oh, dear Beverly. I just took your introductory through advanced class on an artist I did not know - Gabriele Munter - and am astonished by her work and my own ignorance. Merci mille fois for the course and your copious illustrations. Melinda, San Francisco & Paris

New comment on Agnès Varda: inspiration, creation and sharing:

Wonderful article again. I will be in Paris in June with my chorus and will have time to see the show after our concerts. Merci, Susanne

Beverly, I think I already mentioned my love for Varda and the Carnavalet expo which I saw the day before we left Paris. Faces Places remains my favorite documentaries of all time. Another of hers I recommend, if you’ve not seen it, is Rue Daguerre, We lived for 6 months (almost 30 years ago!) very near that street and it remains significant to us. But, of course, it's a fine film if you’ve never even heard of Paris. Melinda, San Francisco & Paris