Revenge may be Sweet but Success is Sweeter

Artemisia Heroine de l’art

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, a review of an exhibition about one of my favorite artists, Artemisia Gentileschi which is at one of my favorite museums, the Jacquemart-André. One thing I appreciate about the museum is its history. Edouard André’s nephews didn’t want to take care of their Uncle Edouard once syphilis began to take its toll, so, clever lads, they convinced the painter, Nélie Jacquemart, a woman of modest means, to marry him. That was in 1881. He was 48, she was 40. For the next 13 years, they traveled extensively and purchased exuberantly. Before he met Nélie, André collected mostly French art. With Nélie, his art horizons expanded. The pair often traveled to Italy where they amassed a collection of Renaissance art by masters only then becoming appreciated in France.

Edouard André died in 1894. The will he wrote under his nephews’ influence gave all of his wealth and property back to his family upon his death. His final will named Nélie his sole heir. The family took her to court, they lost. She inherited everything. For the next 18 years, until her own death, Nélie continued to travel and buy art. And she purchased a 12th C abbey she knew as a child. In her will, she donated her art collection, Paris mansion and 12th century abbey to the Institut de France and the French people. (Fig 1)

Figure 1. Nélie Jacquemart-André, self portrait 1880

The most recent exhibition about Artemisia before this one was in 2022, at the National Gallery in London. It was postponed for six months because of Covid. Lots of exhibitions were scrapped at the time but with this exhibition, there was an unflagging determination to ‘go on with the show.’ And that’s because, as Sheila McTighe (Artherstory) noted in her review of the exhibition, it was "the National Gallery’s first major exhibition devoted to a woman in its nearly 200-year history…” A painting by Artemisia, St. Catherine of Alexandria (1613), (Fig 2) acquired for the museum’s permanent collection in 2018 was the 21st painting by a woman in a collection that contains 2800 paintings by men. With that purchase and this exhibition McTighe contends that one “could claim some progress toward understanding the significance of women’s careers in the .. arts.”

Figure 2. Artemisia Gentileschi as St. Catherine of Alexandria, 1613 (National Gallery, London)

While Ms McTighe celebrated the arrival (finally!) of an exhibition about a female artist into the hallowed spaces of the National Gallery, Wilson Tarbox, in his review of the Jacquemart-André exhibition (Art News, 2025) asks if, “a private institution like the Jacquemart-André, steeped in bourgeois refinement, (can) do justice to a figure as uncompromising as Artemisia?” Tarbox obviously doesn’t know this museum’s history.

The (mostly) female art historians who began writing about Artemisia in the 1980s privileged her biography. They contended that the subjects Artemisia chose to paint and the way in which she chose to paint them, had as their source the traumas she suffered as a girl. More recently there’s been an effort to shift from biography to art history, to contextualizing her work within the framework of other artists active when she was. And yet, to ignore Artemisia’s biography seems wrong. When other female artists were painting mostly still lifes and portraits, Artemisia was painting historical and biblical and mythological scenes, like the guys. So, let’s start with her biography,

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in 1593 in Rome, the eldest child of the painter Orazio Gentileschi. Artemisia’s mother gave birth to 3 sons before she died in childbirth, in 1605, at the age of 30. Artemisia, then 12, was the only female in the family and so it fell upon her to take care of the household and her younger brothers.

In the 17th century, the only way a girl could study painting seriously was if her father was an artist. Luckily for Artemisia, Orazio encouraged her. Her male contemporaries could travel the city, studying classical statues and works by other artists, Artemisia had to stay at home. Learning to paint by copying her father’s painting, learning about anatomy by recording what she saw in the mirror. Artemisia stayed at home because it was too dangerous to be out on the streets of Rome unescorted, unchaperoned. Alas, what her father feared would happen if Artemisia ventured outside, did happen, in their home.

One day in May, 1611 Artemisia was raped by her father’s friend and colleague, the painter Agostino Tassi. He went to the studio when Orazio was out, ostensibly to give Artemisia lessons in painting perspective. After Tasso raped her, he promised to marry her so she continued to have sexual relations with him for 8 more months. When it was clear that Tasso wasn’t going to marry her, couldn’t marry her because he was already married and might have tried to kill his wife and definitely did have sex with his wife’s sister, Orazio took Tassi to court. Not for raping Artemisia but for violating the Gentileschi family’s honor. The trial began in March and lasted through November, 1612.

The trial proceedings have been preserved. Artemisia’s testimony is graphic. Here’s an example of what she told the court, “He then threw me on to the edge of the bed, pushing me with a hand on my breast, and he put a knee between my thighs to prevent me from closing them. Lifting my clothes, he placed a hand with a handkerchief on my mouth to keep me from screaming.” She tried to protect herself by scratching his face and pulling his hair but she couldn’t stop him. Afterwards, she got a knife out of a drawer and threw it at him but he moved out of the way and wasn’t injured.

As we all know only too well, in rape cases, it is the victim who is on trial. During the trial, Artemisia was tortured with a 'sibille' (thumbscrew) to make sure she was telling the truth. As the cords were pulled tighter around her fingers, she screamed, “It is true, it is true, it is true.” Looking at Tassi she said: "This is the ring that you give me and these are your promises.” Tassi was found guilty and exiled from Rome, but he was back in a few months. Because the Pope liked him.

After the trial and with Artemisia now identified all over Rome as ‘spoiled goods,’ Orazio had to find her a husband and get her out of town. Which he did by marrying her off to a modest Florentine painter. Artemisia and her husband lived in Florence for the next 7 years. During which time she gave birth to five babies and although she must have been pregnant most of the time and caring for a newborn, too, she kept painting. Her career flourished, she was the first women to become a member of the Accademia di Arte del Disegno (Academy of Fine Arts) in Florence. She received commissions from the Grand Duke Cosimo II and other members of the Medici clan. She met and became friends with Galileo. She finally learned to read and write. She tried her hand at poetry and learned to play the lute. (Fig 3) She even had time for a lover, as recently discovered letters confirm. The letters she wrote to her Florentine nobleman lover are filled with passion, humor and grammatical errors! In one letter she refers to a self portrait that she gave him and warns him not to masturbate in front of it. In the same letter, she tells him that she is happy that he hasn’t taken any lovers other than his ‘right hand.’ Artemisia’s husband was not cuckolded. His letters to her lover, which have also recently been found, confirm this. He was a pragmatic man, happy that someone was helping his wife get commissions, preferring a wife who was earning money to one who was being faithful.

Figure 3. The Lute Player, self portrait, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1615

But Artemisia and her husband were spending money faster than she could make it. Threatened by creditors, they fled Florence for Rome. Within three years, her husband had disappeared and the fourth of her 5 children had died at age 5. (Fig 4) Those losses, perhaps coupled with the memory of her own mother’s death in childbirth, must have weighed as heavily on her psyche as her rape. Alone with her daughter, Artemisia moved to Venice where she lived from 1626 to 1630. Here she had poems dedicated to her by Venetian authors and was linked to a circle of aristocrats, writers and intellectuals.

Figure 4. Sleeping Putto, Allegory of Death, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1620

When Artemisia left Venice in 1630 for Naples, she was probably fleeing the plague. Naples was where she stayed for the rest of her life, except for four years (1638 to 1642), when she went to England to help her father complete a commission for Charles I’s wife, Queen Henrietta. She stayed to complete commissions she received. Mostly, though Artemisia was in Naples. Which is where she probably died in 1656, at the age of 62, a victim of the plague that swept through the city, killing 150,000 people, half the city’s population and an entire generation of Neapolitan artists.

In the 1990s, I began teaching a course I called “Women as Artists / Women as Art.” It was an introduction to art herstory. For my lectures on Artemisia, I assigned John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972). Among the many chestnuts in this book, are these: Men act and women appear. A man's presence suggests what he is capable of doing to you or for you. A woman's presence … defines what can and cannot be done to her.’ ‘Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.’ About the female nude in European oil painting, he wrote: “the painters and spectator-owners were usually men and the persons treated as objects, usually women…The implication (is) that the subject (a woman) is aware of being seen by a spectator. Often - as with the subject of Susannah and the Elders - this is the actual theme of the picture. We join the Elders to spy on Susannah taking her bath.” She is depicted either looking at herself (in a mirror) or looking at us looking at her.

Artemisia’s first major painting, from 1610, is her version of this Old Testament story. She painted it one year before she was raped by Tassi. But surely not before she had begun to experience unwanted looks from the men in her father’s studio. (Fig 5)

Figure 5. Susannah and the Elders, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1610

In Artemisia’s depiction, Susannah’s expression is tormented, her gesture is defensive. She tries to shield herself from her intruders. The story is this, two old guys surprise Susannah in her garden, at her bath. They tell her that unless she has sex with them, they will tell her husband that they saw her committing adultery, a crime punishable by death. She refuses to have sex with them. She is brought to court where the wise judge Daniel questions the men separately. The inconsistencies of their story are revealed. Susannah is exonerated.

By looking at how male artists treated this theme, we can see that Artemisia is coming at the story from another place, a female place. Mary Garrard noted in her 1989 monograph on Artemisia, that Artemisia’s version is the first in which sexual predation is depicted from the point of view of the victim and not the predators. (Figs 6 - 9) “With this painting, and with many other works that followed, Artemisia claimed women’s resistance to sexual oppression as a legitimate subject of art.” According to the curators, she demonstrates a particular sensitivity to the plight of vulnerable women. (Figs 10, 11)

Figure 7. Susannah and the Elders, Tintoretto - Susannah opens her legs for the viewer & admires herself in a mirror

Figure 8. Susannah and the Elders, Guido Reni, a compressed space but Susannah is not particularly distressed

Figure 9. Another version of Susannah and the Elders by Tintoretto. She looks out at the viewer while her maids prepare her body and the Elders look on, more like Peeping Toms than tormentors

Figure 10. Susannah and the Elders, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1640 when she was in England for Queen Henrietta. The scene is frontal although Susannah hides herself from the viewer. She is less tormented but still disturbed

Figure 11. Susannah and the Elders, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1660. This is the last known painting by Artemisia. Susannah is fully clothed here and her gesture rebukes the Elders under an ominous sky.

Although Artemisia’s paintings of women have been described as self-portraits, [her hair color (auburn) facial features (round cheeks) and body type (full)] Letizia Treves, the curator of the National Gallery show believes that Artemisia’s understanding of the female body is more important. That it is what separates her female nudes from those of her male colleagues. One look at Michelangelo’s female nudes proves her point. (Fig 12)

Figure 12. Notte, Michelangelo, Medici Tomb, Florence

Here’s one of Treves’ examples, Artemisia’s 1612 miniature on copper, “Danaë,” (Fig 13) a delicate nude who lies upon a bed as Zeus impregnates her with a shower of gold. “Creases around the figure’s armpits and swells in the stomach reveal an awareness of the way a woman’s flesh settles and subsides.” By contrast, her father’s “Danaë” (early 1620s) features breasts that “defy gravity with an almost comical perkiness.” (Fig 14)

Figure 13. Danaë, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1612

Figure 14. Orazio Gentileschi, Danaë. The bedsheets are as convincing as Artemisia’s but the breasts - no so much!

Artemisia’s depictions of the Old Testament story, Judith and Holofernes has long been interpreted along biographical lines. It’s what a woman who has been wronged by a man would like to do to that man. Artemisia depicts Judith either hacking off Holofernes’ head or carrying his head in a basket. (The story is that the brave widow Judith, aided by her maidservant, kills the Assyrian enemy general Holofernes to save Israel.) A comparison of Artemisia’s versions of those scenes with ones by male artists shows how charged Artemisia’s choices are. To me, the enthusiasm with which Judith hacks off the head of Holofernes can be compared with how David goes about the same task with Goliath in paintings by Caravaggio. His life story perhaps informing his own visceral response to a weak boy threatened by a much bigger, stronger man. (Figs. 15-17)

Figure 15. Judith and Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi. Both Judith and her servant show strength & determination

Figure 16. Judith and Holofernes. Caravaggio. Judith delicately saws Holofernes head off. He seems surprised rather than flighting for his life.

Figure 17. David with the head of Goliath, Caravaggio

In this exhibition Artemisia’s painting of Judith with her Maid servant is juxtaposed with Orazio’s painting of the same scene. His was Artemisia’s source. Yes, but …her compositional changes make her telling of the story much more compelling. (Figs 18-21)

Figure 18. Judith and her Servant after they have cut off Holofernes head, they hear something, will they be found?

Figure 19. Judith and her Servant, Orazio Gentileschi (Artemisia’s model)

Figure 20. Judith and her servant with the head of Holofernes, Botticelli - what a beautiful elegant warrior

Figure 21. Judith and her servant with head of Holofernes and body of Holofernes in bed on right. Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel

The feminist art historian Griselda Pollock suggests that rather than seeing these Judith paintings as revenge images, we should celebrate them as images of political courage. The collaboration of Judith and her maid servant during war time interpreted as an act of ‘daring political murder.’ As Pollock argues, we know that Artemisia achieved success during her career, in the various places that she lived and worked. So it is only reasonable to assume that she produced paintings for patrons of subjects they selected. These subjects were ones that reflected contemporary tastes for dramatic depictions of biblical, historical and classical heroines. Rebecca Mead concurs, it’s just possible that “the fact of having been raped was less significant to Artemisia’s sense of self than some of her modern champions have suggested.”

As Judith Mann wrote in a review of an exhibition on Artemisia (Rome in 2001), the stereotypes of Artemisia that preceded our own era was of a sexually immoral woman who had cuckolded her husband. That was replaced by the stereotype of Artemisia as the wronged young woman. Exchanging one stereotype for another does a disservice to the artist by suggesting that unlike her male contemporaries, the only prism through which Artemisia’s art can be viewed is biographical. According to Mann, “Without denying that sex and gender can offer valid interpretive strategies for the investigation of Artemisia's art, we may wonder whether the application of gendered readings has created too narrow an expectation.”

Of course it has, expectations are like blinders. We expect Artemisia to depict strong, assertive women. We are not prepared to appreciate her depictions of the Virgin Annunciate or the Madonna and Child. As Mann notes, “this stereotype has had the doubly restricting effect of causing scholars to question the attribution of pictures that do not conform to the model, and to value less highly those that do not fit the mold.” In this exhibition there are paintings by Artemisia that don’t fit the mold, like a Madonna and Child in which we marvel at the naturalism of a mother offering her nipple to her infant and her infant lovingly reaching for his mother. (Fig 22)

Figure 22. Madonna and Child, Artemisia Gentileschi

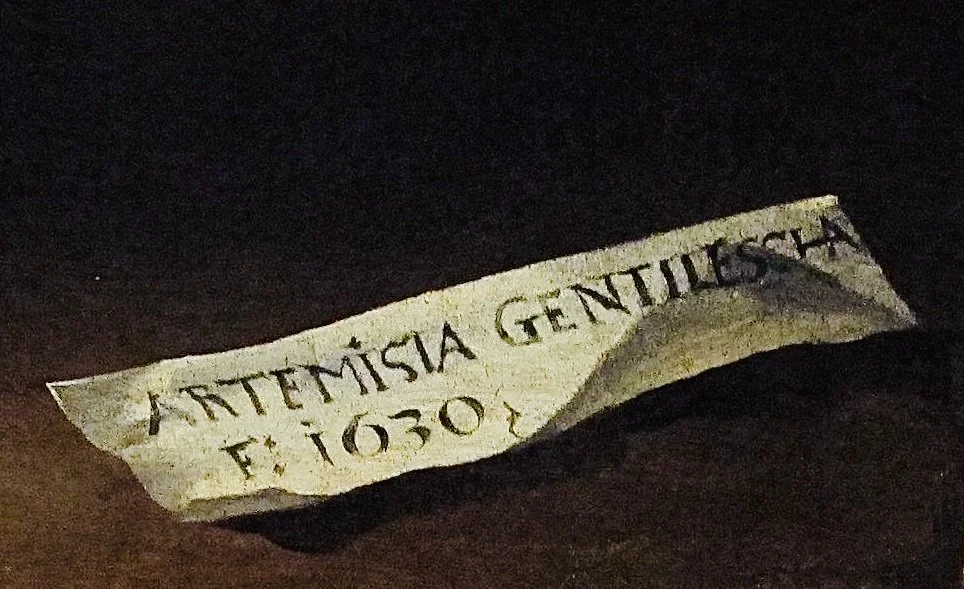

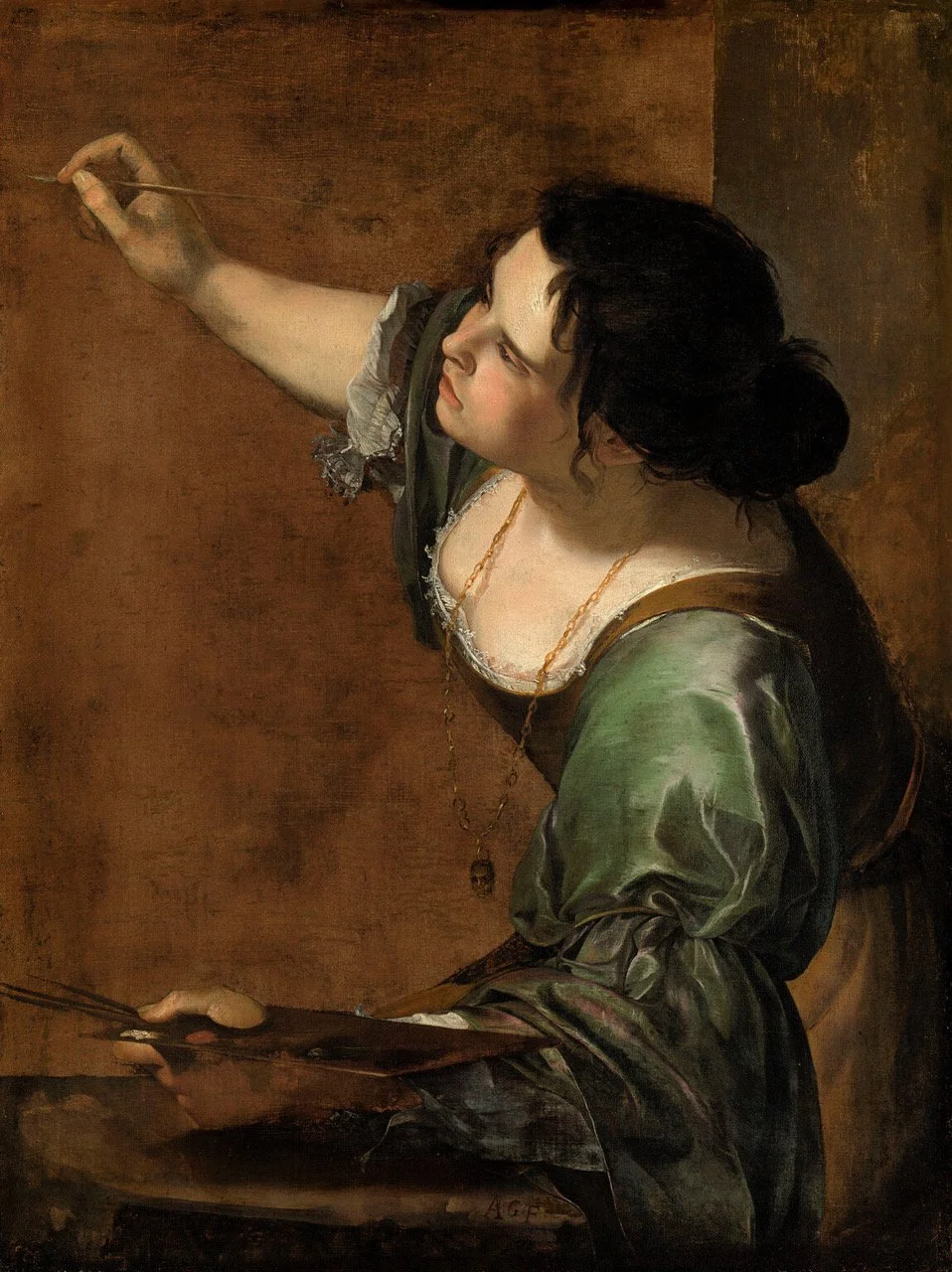

When Artemisia was in England, she painted “Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting,” (La Pittura) (Figs 23, 24) In self-portraits, the artist/sitter normally looks at the viewer, at the mirror. In this image, the sitter concentrates on the canvas, poised to begin painting, a brush in one hand, her palette in the other. The neckless she wears the same as the one worn by the Allegory of Painting in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia. She’s not posing, she’s working. It’s a conceit only available to a female artist because only a female artist can paint herself as herself and as an allegorical representation of her profession. As the curators of this exhibition tell us - Artemisia’s paintings speak to us through their audacity, singularity, and power. Indeed. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 23. Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, “La Pittura” 1540

Figure 24. La Pittura, Iconologia, Cesare Ripa - they both wear the same necklace