Petit Prince + Marcel Proust = David Hockney

David Hockney 25 FLV

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. We’re back at the FLV for one more look at the work of David Hockney. If you are wondering whether I am the only person locked in superlatives about this artist and this exhibition, herewith a sampling of what others have written. Jonathan Jones (Guardian, April 2025) wrote, “Hockney is as reliable as…daffodils, returning at 87 as he did at 82 to show us how beautiful the world is in spite of those who try so hard to ruin it.” Emily LaFarge (NYT, April 2025) wrote, “It’s a joyful vision, and a record, of a life in art lived with passionate curiosity, attention to the human condition and reverence for the natural world.” Cecelia Rodriguez (Forbes, April 2025) wrote that Hockney’s “…explosion of colorful, relatable, joyful and immersive works …communicat(e) the artist’s joie de vivre and bring(s) smiles of delight - and sometimes even gasps - to observers.” Finally, Jackie Wullschläger (Financial Times, April 2025) wrote, “Youth and age, memory and desire, time lost and regained, are the threads uniting a very diverse show; in the superb catalogue co-curator Suzanne Pagé notes that if Hockney expresses the childlike wonder of The Little Prince, he is also a devotee of Proust.”

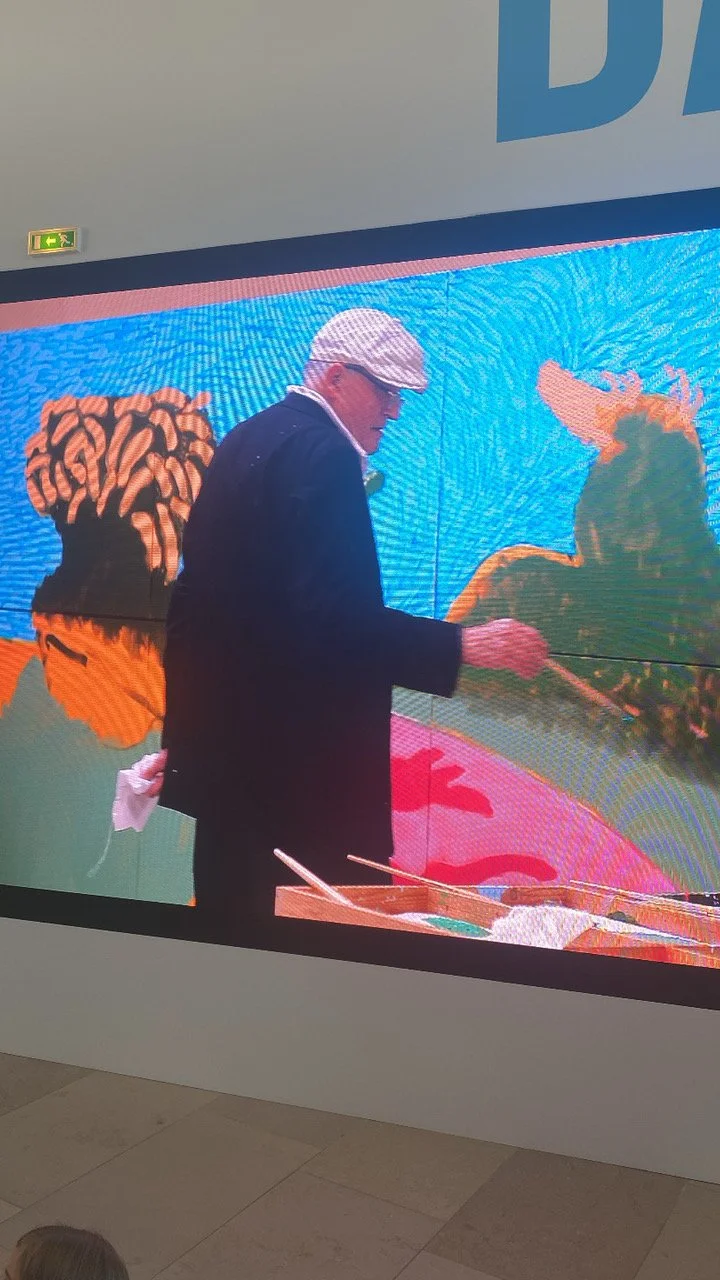

Images of David Hockney painting pop up everywhere in the corridors of the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Here he is painting ‘Winter Timber’ 2009, oil on 15 canvases

Here he is painting May Blossom on Roman Road, 2009, oil on 8 canvases

I was going to dedicate this missive entirely to Hockney and Proust but there were too many other things I want to tell you about, like his mise en abyme (pictures within pictures), his riffs on works by Cézanne, Munch and Hogarth and finally, his set designs and costume designs for the opera. We’ll start with Proust, of course.

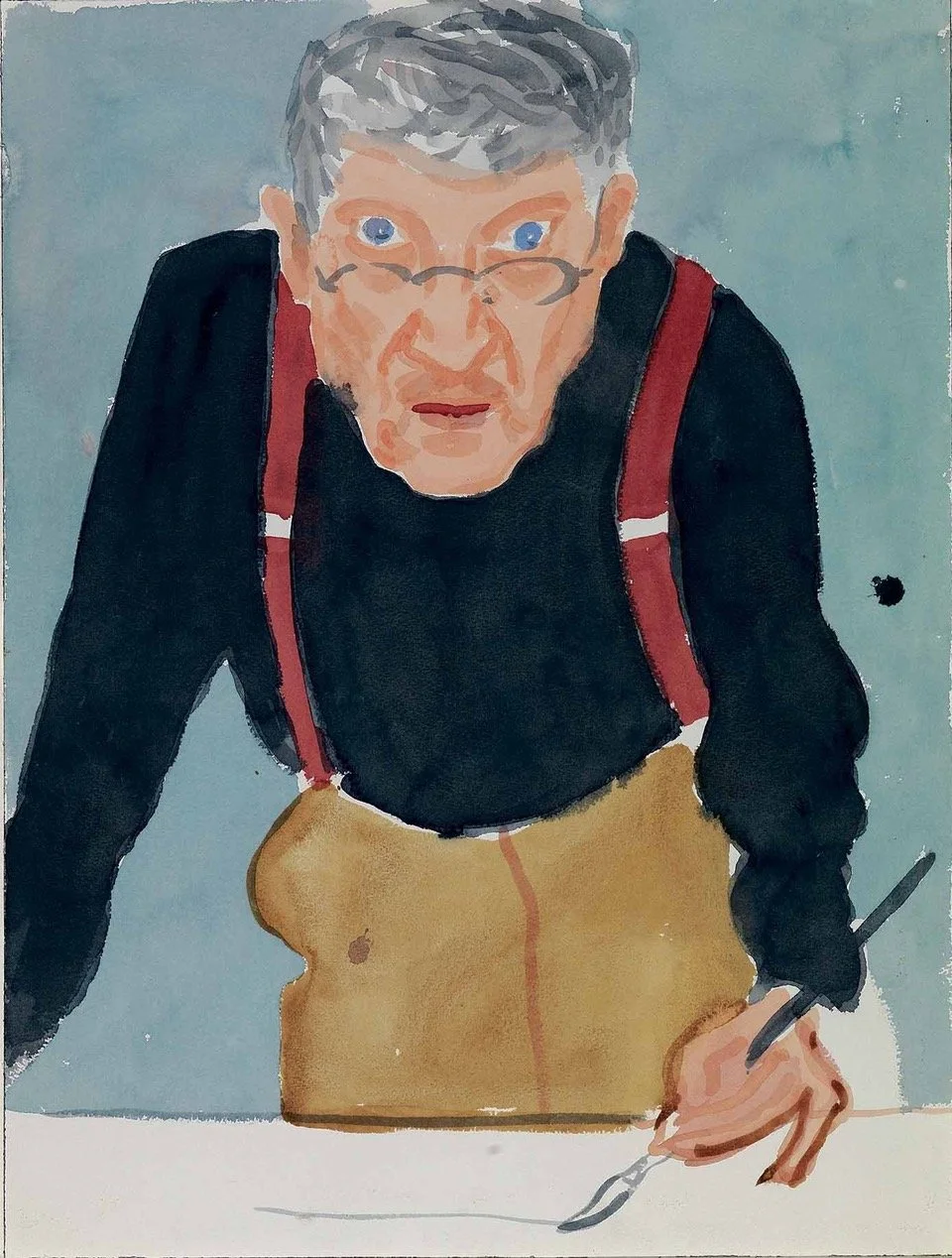

David Hockney, “Self Portrait with Red Braces,” 2003.

For those of you who have successfully or not, read all or portions of In Search of Lost Time, you know that Proust takes a long time to get to his point, if there is a point. Descriptions are long, sentences are longer. You can’t hurry Proust (kind of like what Diana Ross and the Supremes told you about love). I think since very early on in his career, Hockney has sought to incorporate time into his images. He wants people to linger as they look and so he has devised methodologies, sometimes using the most modern technologies like iPads, sometimes the most ancient ones, like Chinese scrolls and the Bayeux Tapestry, to produce works that require continued looking.

David Hockney was 21 when he first read In Search of Lost Time. As Nicolas Ragonneau (Proustonomics, April 2025) writes, when Hockney first read Proust, “his background was far removed from the Proustian world: he had never seen asparagus and knew nothing about society dinners with duchesses. Yet he was struck by the ‘wonderfully visual’ quality of In Search of Lost Time, retaining the memory of the pages Proust devoted to a curtain swaying in the breeze.” I can imagine that Hockney didn’t have much experience with society dinners with duchesses, how many of us do? But asparagus? Even if fresh vegetables were hard to find in post war England, surely art student Hockney knew Manet’s paintings of asparagus. They were my ‘way in’ to Proust.

Proust was on Hockney’s mind in 1976, 1977 when he painted two double portraits of his parents seated, separated by a table on the bottom shelf of which, in both portraits, are several volumes of Scott Moncrieff’s English translation of Proust. (Figs 1, 2)

Figure 1. 'My parents' 1976.

Self portrait in the mirror, Moncrieff’s English translation of Proust stacked upright on the table between them, 1976 (all images by Hockney unless otherwise noted)

Figure 2. My parents, 1977.

Mother’s pose slightly different, her chair now matches her husband’s. Hockney's father is actively reading rather than pensively sitting with his hands in his lap. There’s a different bouquet on the table, 5 volumes of Proust are now stacked upright on mother’s side. The drapery above Hockney’s parents’ heads is gone and so is Hockney’s self portrait in the mirror. Instead, in the mirror is the reflection of the drapery and a postcard (?) of Piero della Francesco’s Baptism of Christ. (Fig 3)

Figure 3. The Baptism of Christ, Piero della Francesca which you can see in the mirror in Figure 2

By 1983, Hockney had read Proust a second time as reported by a journalist who interviewed him in London that year (‘Shapers of the 80s’). “Few of us have read Proust’s 20th-century masterwork, A la recherche du temps perdu… It is impressive but by now unsurprising to hear that Hockney has read the epic twice.” The journalist continued, “I find myself in the midst of an exhilarating tutorial from Hockney… He has always been an explainer about how we use our eyes, about the act of looking, and what he has recognized in Proust is his technique for showing the reader around his world, like a tour guide whose detailed descriptions legendarily go on for page after page…Hockney makes the observation, self-evident only with hindsight, that the act of looking around Proust’s world takes time – that spending time with Proust is about duration.”

According to Laurette Long, “Proust’s ideas about time, perspective and the observer, greatly influenced (Hockney) as did his theories about the role of art”. Proust wrote, “Only through art (by which he meant painting, literature, music) can we get outside of ourselves and know what another person sees of this universe which is not the same as ours…Thanks to art, instead of seeing a single world, ours, we see it multiplied …” In his 1993 book, ‘That’s the way I see it,’ Hockney, channeling Proust, wrote, ‘My duty as an artist is to overcome and alleviate the sterility of despair…new ways of seeing mean new ways of feeling.’”

And when did Hockney read Proust for a third time? During the pandemic, of course! Adam Watt, in his 2021 TLS review of Hockney’s book ’Spring Cannot be Cancelled, David Hockney in Normandy, 2021’ writes that Hockney’s work has many Proustian qualities. Like Proust (who characterized Normandy apple trees in blossom as standing …dressed for a ball with their feet in the mud), Hockney “lives an intense connection to his surroundings and their interaction with the weather, every breath and whisper, shadow and sparkle observed, appraised and enjoyed.”

Hockney sees connections between Proust’s descriptions, the passage of time and Cubist paintings. It’s complicated and fascinating and I’ll tell you about it one day. Because as so often happens to me, one artist, whose work I admire and ‘get’ becomes my ‘conduit’ into the work of artists whose works don’t immediately call out to me.

Let’s see, what else? The mise en abyme paintings, the picture within a picture paintings, of course. In one room there are 20 flowers portraits painted by Hockney between January and April 2021. When it was too cold to work outside in Normandy - a problem he would not have encountered had he gone to L.A. Just saying. Here’s how Hockney explained it, “I was just sitting at the table in our house, and I caught sight of some flowers in a vase on the table. A few days later I started another from the same position with the same ceramic vase. This took longer to do. I then realized if I put the flowers in a glass vase the sun would catch the water, and painting glass would be a more interesting thing to do. So then I was off.”

Some of the flowers are local and seasonal, others are exotic. Each bouquet is in a modest container, nothing fancy - vase or jug, ceramic or glass - mostly on a blue, sometimes on a red gingham (vichy) checked tablecloth. All of the flower paintings are set against the same burgundy wall of the dining room of Hockney’s house in Normandy. Hockney composed these still lifes on his iPad. Later he had them framed in ornately carved wooden frames. Hockney explained the juxtaposition of frames and prints this way, "They look startling because the frames are very hand-done in an old way and my pictures are also hand-done in a new way: the iPad.” (Figs 4-6)

Figure 4. Flowers in a vase in Normandy, iPad painting printed on paper, 21st April 2021

Figure 5. Flowers in a vase in Normandy, iPad painting printed on paper, 19th March 2021

Figure 6. Flowers in Vases in Normandy, iPad painting printed on paper, 2021

One year later, in a painting called “25th June 2022, Looking at the Flowers (Framed)” the iPad bouquets are all together, as if for their final bow. The sapphire blue wall against which they are arranged has been replicated at the FLV. David Hockney is also in this painting, twice, looking at the flower portraits just as we are. The exhibition catalogue calls the painting “a surprising self-portrait: the artist and his double comfortably seated in an armchair, contemplating their finished work.” But which one is the ‘real’ David Hockney and which one is the double? (Fig 7)

Figure 7. 25th June 2022, Looking at the Flowers (Framed) , 2022

The Hockneys are not mirror images of each other. They are dressed identically, that’s true, although a puff of cigarette smoke emanates only near the Hockney on our left. The chairs upon which each Hockney sits are different as are the low tables closest to them. The left side Hockney sits on a period chair next to a small wooden table upon which a 21st flower portrait makes an appearance. The right side Hockney sits on a wicker chair. (I have one like that from Ikea). On the low wicker table next to him are two packs of Camel cigarettes (one for each Hockney?) a bottle of Evian (large enough for two Hockneys) one ash tray and alas, only one glass.

Hockney calls the technique he used to compose this self portrait, "photo-graphic drawings.” He photographed each element from all angles. The different points of view were then computer-manipulated and assembled into a single space, where the fourth dimension - time - is introduced: according to Hockney, the eye must observe each element separately, "unlike an ordinary photograph which you see all at once.”

The flower paintings were first published in a special edition of the German daily, Die Welt. In this painting, three neatly folded issues of that newspaper sit on the lower shelf of the table on the right. (Fig 8)

Figure 8. Die Welt, one of flower paintings by Hockney (Figure 5 above)

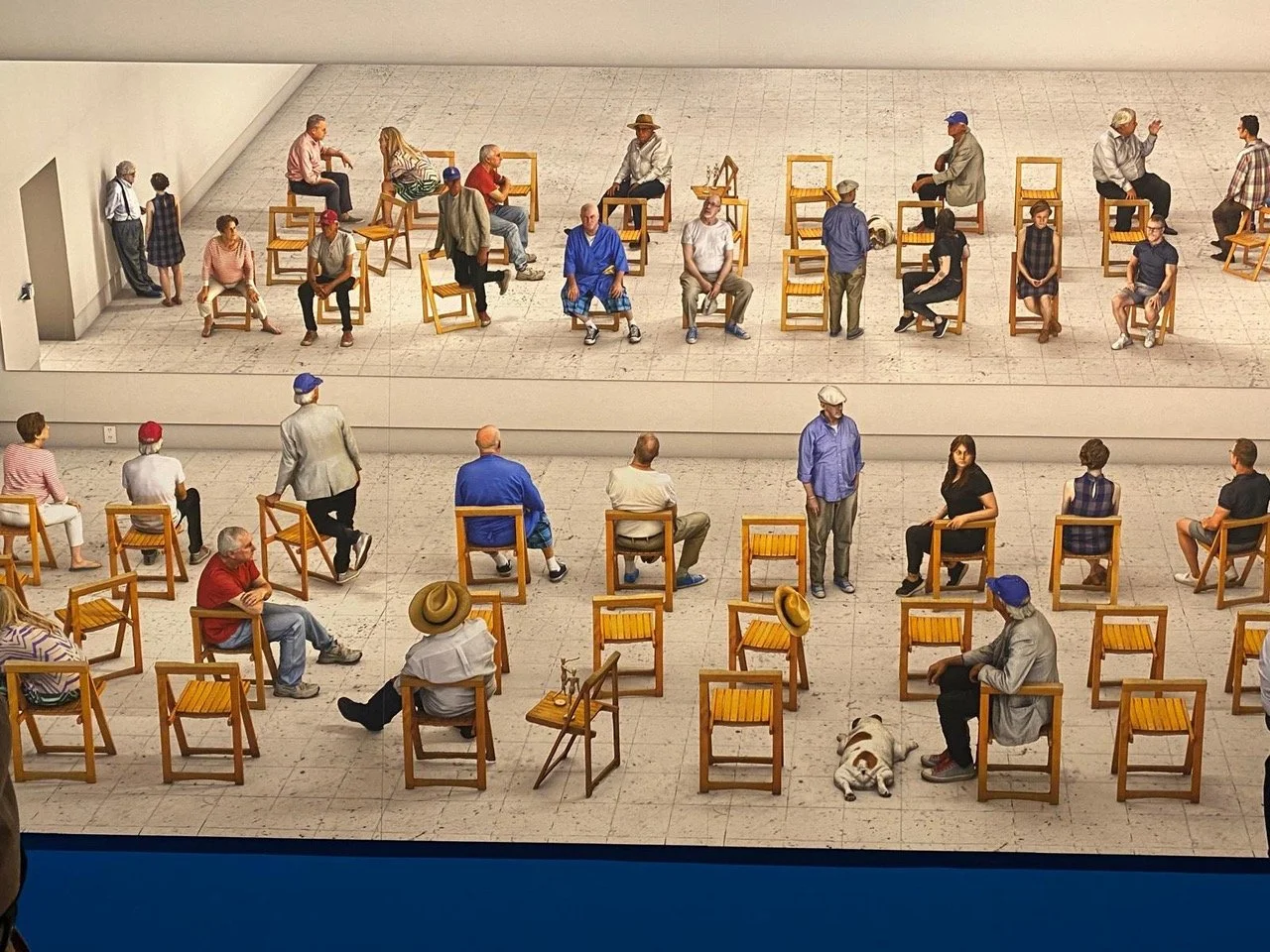

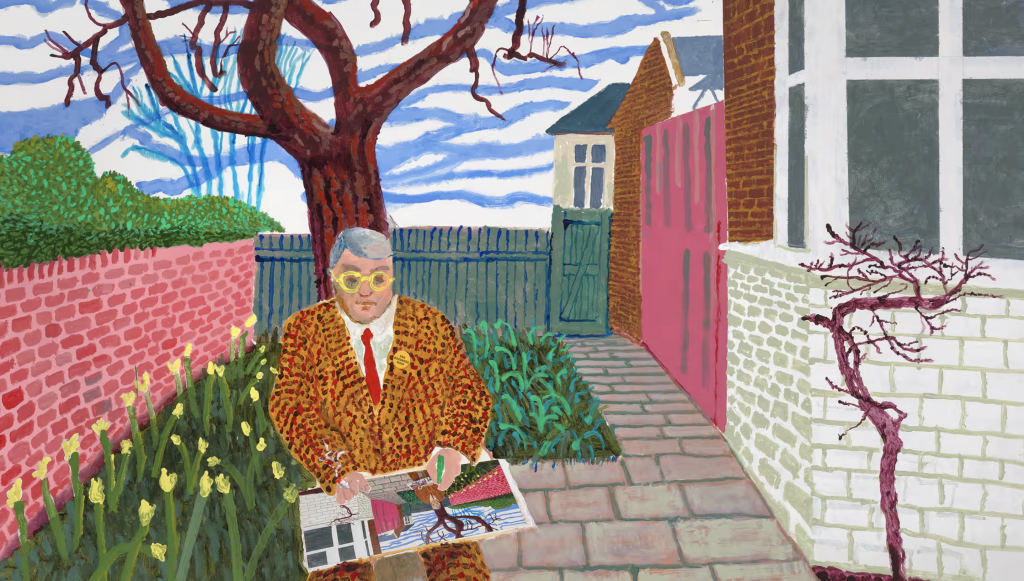

In another room, holding its own alongside two huge works filled with people looking at their reflections in a mirror in a space that isn’t real and who were not in the same room at the same time (Figs 9) (it’s complicated, trust me) hangs his most recent self-portrait, called “Play within a Play within a Play and Me with a Cigarette”. (Fig 10) Hockney has depicted himself nattily dressed in a tweed suit, sitting in his garden, with wild daffodils announcing the arrival of spring. On his lap is a painting he’s working on. Which is the painting we are looking at! Hockney doesn’t call his painting a picture within a picture but a play within a play - a reference to literature in general and maybe Shakespeare in particular, a master of the play within a play genre. On Hockney’s lapel is the button I mentioned in an earlier post, ‘Stop Bossiness Soon.’ The button wasn’t Hockney’s first foray into slogan making. His friend Henry Geldzahler, whose portrait by Hockney we saw last week, “claim(ed) that one of (Hockney’s) favorite phrases was “I know I’m right”. Hockney was so amused by Geldzahler’s comment that he had tee shirts printed with the slogan, “I know I’m Right! D Hockney”. (M Gayford, Guardian, 2024)

Figure 9. Pictured Gathering with Mirror, 2018

Figure 10. Play within a play within a play and me with a cigarette

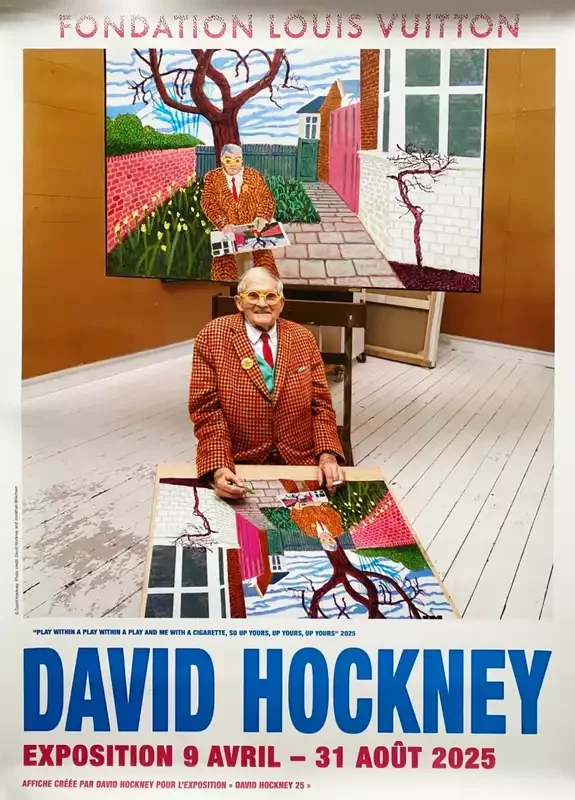

Hockney’s idea for the poster to plaster in Paris metros to advertise his exhibition was this: a photo of himself sitting on a chair in the corner of a room (his studio?) holding the painting he is holding in the painting we have just been discussing. (Fig 11) And the painting itself is just behind him, propped up, maybe on shipping crates. Talk about Meta. But it was not to be. According to the The Independent, (April 2, 2025) lawyers for the Paris transportation system contacted Hockney “to inform him that a photograph showing him sitting alongside a new self-portrait cannot be used to advertise the show.” Why? Because Hockney is holding a cigarette in the photograph, of course. They didn’t object to the paintings of Hockney smoking, only the photograph. Hockney fumed to The Independent,’The bossiness of those in charge of our lives knows no limits. To hear from a lawyer from the Metro banning an image is bad enough but for them to cite a difference between a photograph and a painting seems, to me, complete madness.”

Figure 11. Play within a play within a play and me with a cigarette within a play, 2025

Figure 11a. Pattern Play with a Cig.

Hockney, who has been demonstrating for years that photography, with the assistance of technology, when manipulated artistically, becomes art, was quite naturally, furious. It reminded me of the customs officials in the United States who taxed Brancusi’s sculpture Bird in Space at the high rate applied to ‘domestic utensils' rather than the low rate applied to art because Brancusi’s sculpture didn’t look like art to them, it looked like a utensil. (Fig 12). A (very amusing) court case followed. Brancusi won.

Figure 12. Bird in Space, Constantin Brancusi

I would love to tell you about Hockney’s riffs on and conversations with artists from the past, like Fra Angelico and Claude Lorraine; William Blake and Edvard Munch; Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. (Figs 13-20) But that will have to wait until another time. I’ll finish my review with a look at how Hockney was inspired by the 18th century English artist - William Hogarth.

Figure 13. Annunciation after Fra Angelico

Figure 14. Annunciation, Fra Angelico, San Marco, Florence

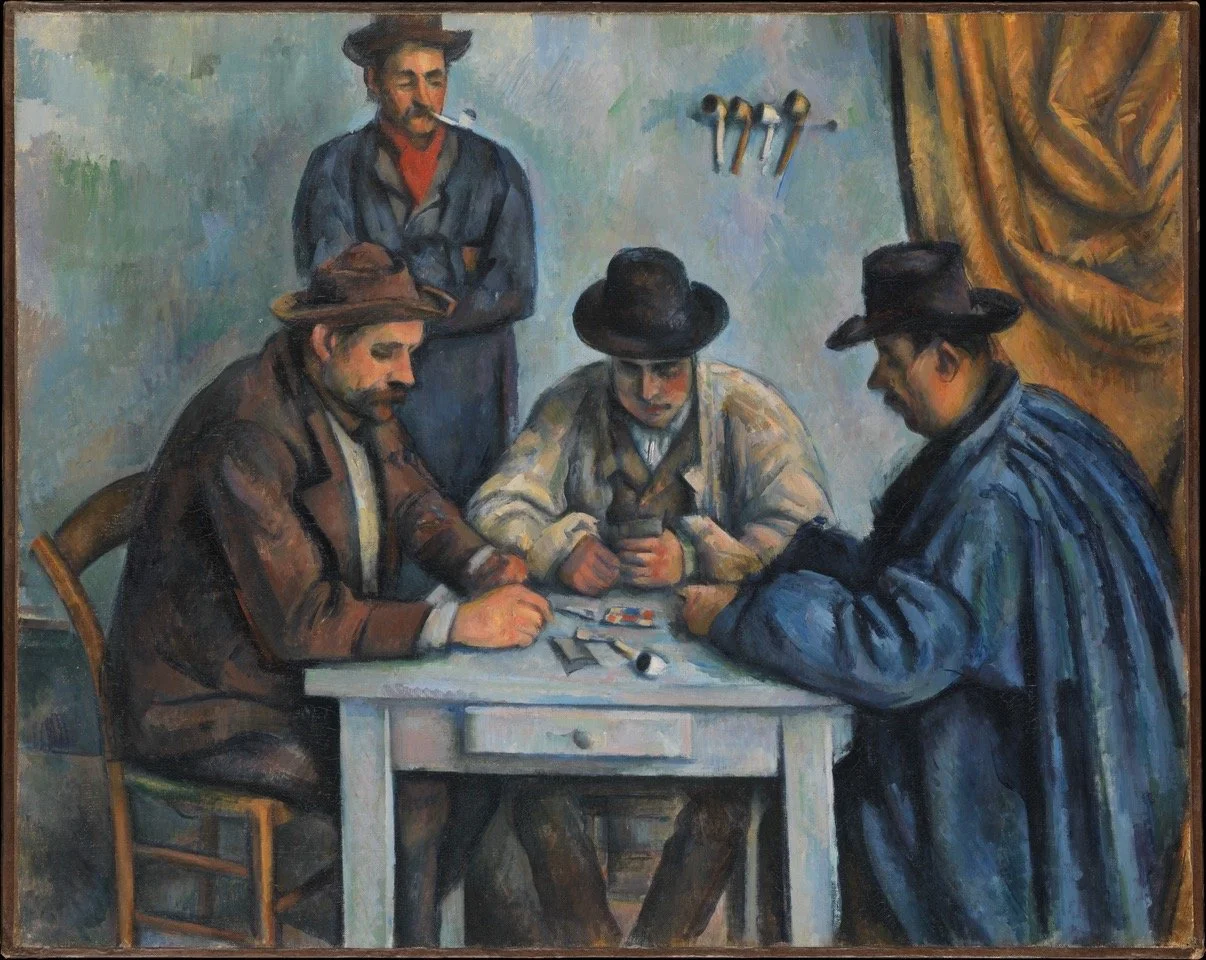

Figure 15. Card Players after Paul Cezanne

Figure 16. Card Players, Paul Cezanne - this image, with the standing figure on left is closer to the painting of Card Players on the top left of Figure 15.

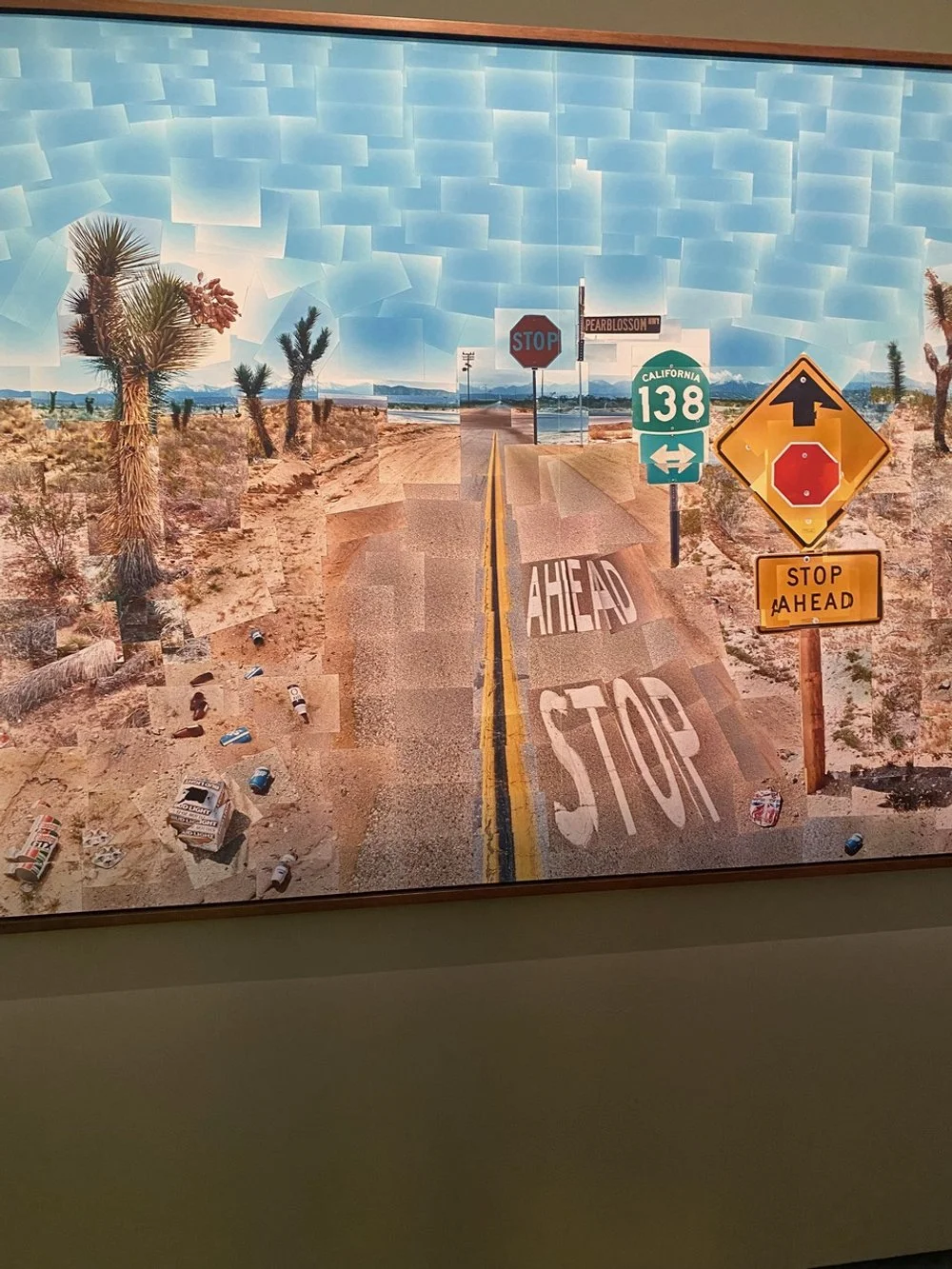

Figure 17. Pearblossom Highway, collage composed of over 700 photographs, 1986

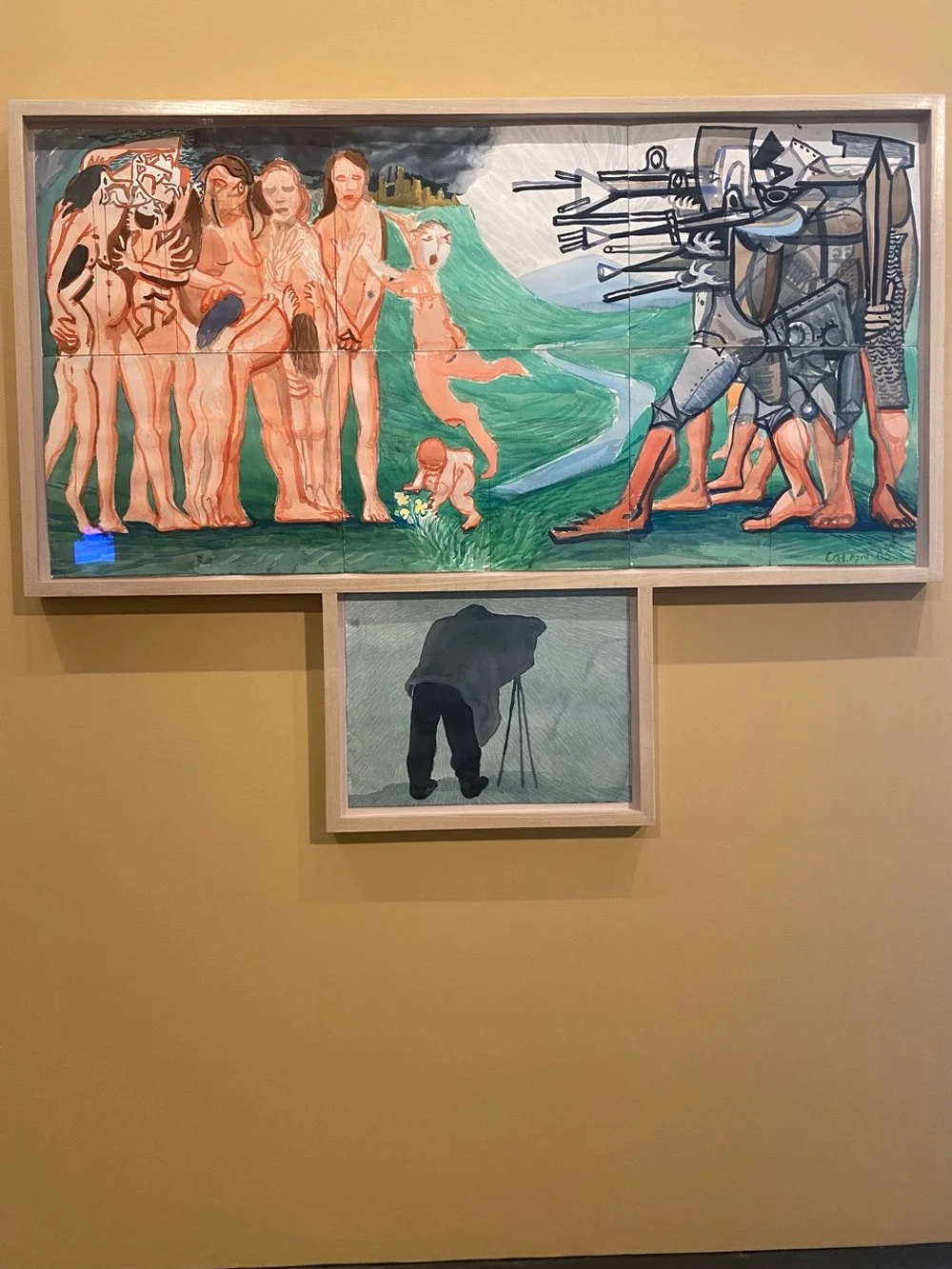

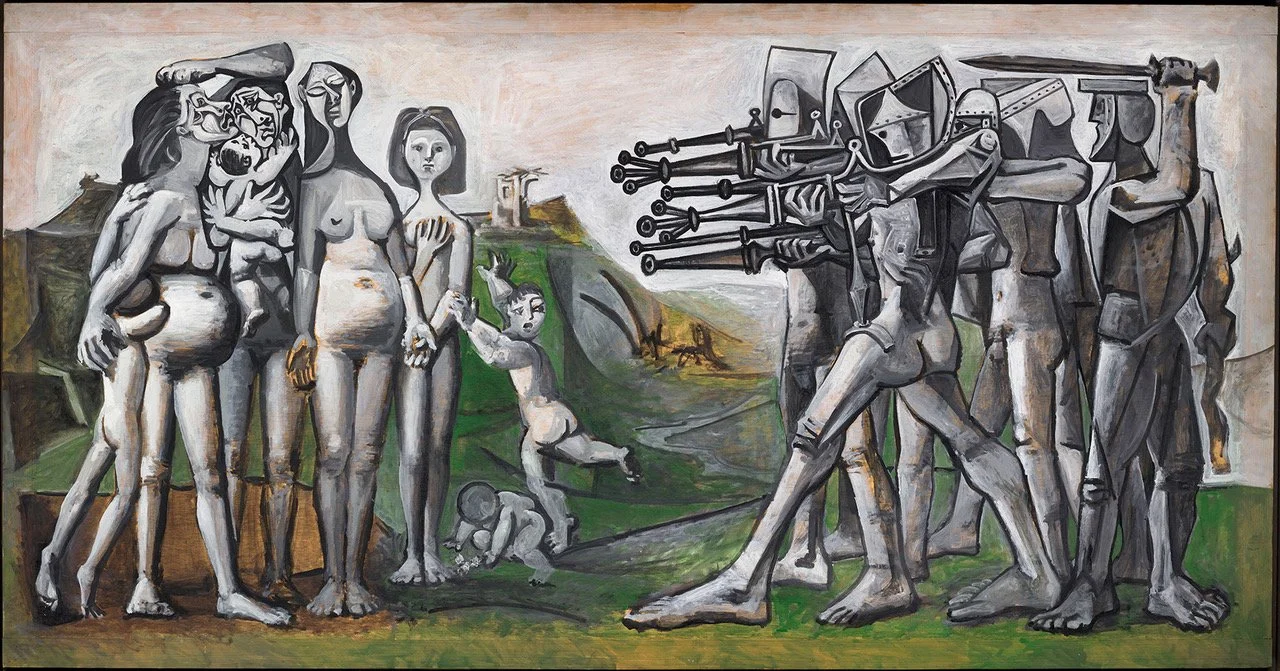

Figure 18. The Massacre and the Problems of Depiction, 2003. After Picasso’s Massacre en Corée, a photographer below group, a reference to photojournalism or posed portraiture

Figure 19. Massacre en Corée,Pablo Picasso, 1951

Figure 20. The Third of May, 1808, Massacre of Spanish by French soldiers, Francisco Goya, 1814, upon which Picasso’s Massacre in Korea is based which is the inspiration for Hockney’s The Problems of Depiction

Hogarth’s Rakes Progress started out as a series of 8 paintings (1732-33). From which the artist made an engraved version three years later. It’s a cautionary tale of a young man with a modest inheritance who spends it all on alcohol, gambling and prostitutes and who ends up in an insane asylum. The engraved series is better known, probably because the story is more easily grasped in black and white and shades of gray. (Figs 21-22)

Figure 21. A Rake’s Progress, Tavern Scene, William Hogarth, 1732

Figure 22. A Rake’s Progress, Asylum Scene, engraving, William Hogarth, 1735

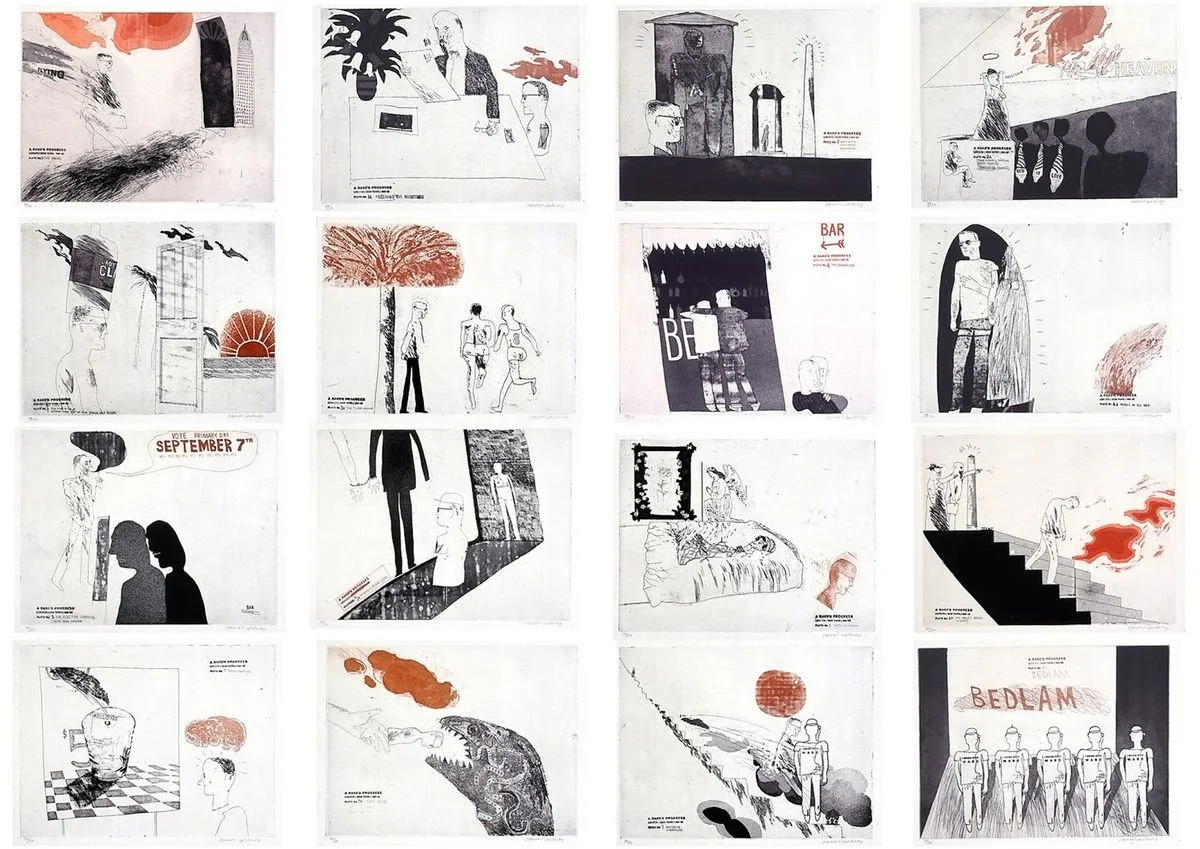

Hockney created his own series of two tone etchings in the early 1960s, entitled A Rakes Progress and loosely inspired by Hogarth’s moralizing tale. Through his etchings, Hockney processed his experiences of coming to the United States for the first time, in the early 1960s, as a young, gay man. Hockney's hero has Hockney’s physiognomy and wears Hockney’s glasses. (Figs 23, 24)

Figure 23. A Rake’s Progress, etching. Arrival in New York, 1961

Figure 24. A Rake’s Progress, etching. All 16 scenes - beginning with Arrival in New York, ending with Bedlam

In 1975, Hockney painted his version of Hogarth’s 1754 engraving, ‘Satire on False Perspective,’ which Hogarth produced to illustrate his friend Joshua Kirby’s pamphlet on linear perspective. The caption under the engraving reads: “Whoever makes a Design without the Knowledge of Perspective will be liable to such Absurdities as are shewn in this Frontispiece.” Hogarth’s engraving warned about what can go wrong if perspective isn’t understood and followed, Hockney, who has always battled against the strictures imposed by such a limited way of seeing and reproducing ‘reality’ surely delighted in the possibilities. Both engraving and painting are filled with humor as planes merge and the placement of the figures, objects, and landscape details obey a logic that defies ‘reality’. Nothing we think we see is actually possible. (Figs 25, 26)

Figure 25. Satire on False Perspective, William Hogarth engraving, 1754

Figure 26. Kerby (after Hogarth) Useful Knowledge, 1975

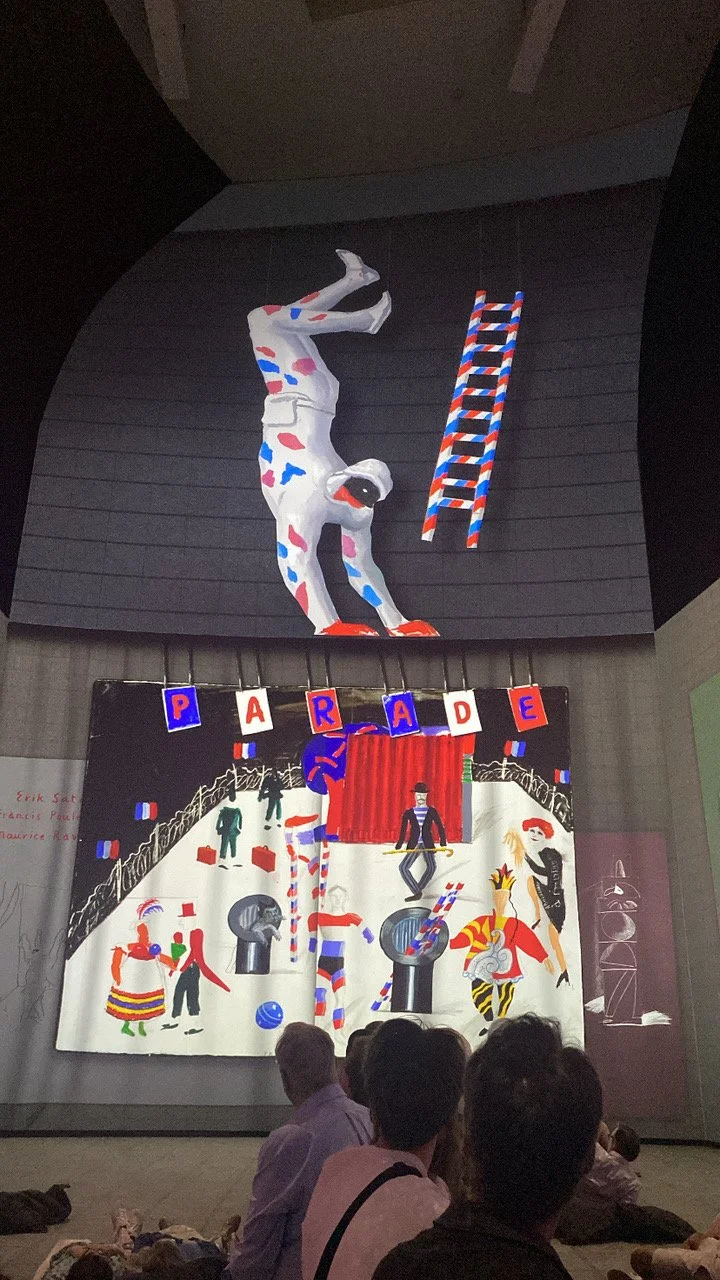

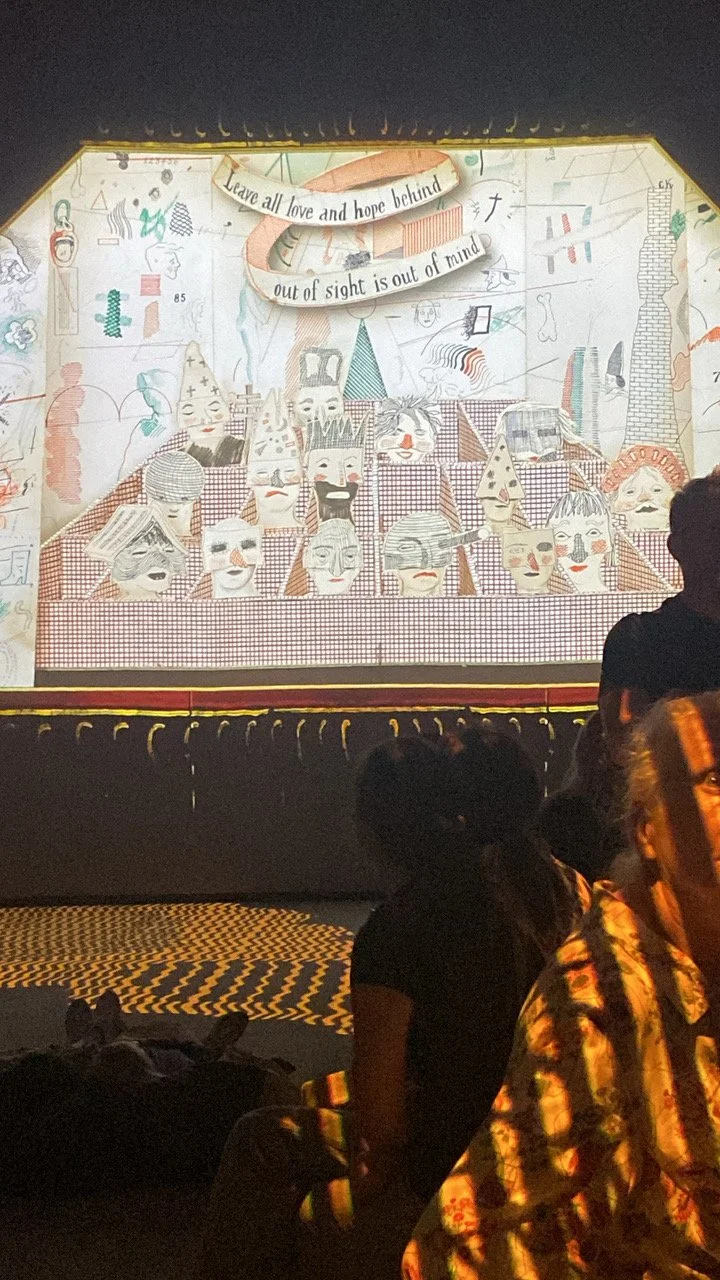

The last room in this extravaganza of an exhibition is called ‘Hockney Paints the Stage.’ It is a musical and visual reworking of Hockney’s drawings and sets and costumes for various operas. The room is dark, there are benches and poofs scattered around the carpeted space to relax upon. The experience is immersive as images emerge from behind, alongside and in front of you. Images that take you into the world of Hockney operas, not clips from actual operas but visuals designed for this space. (Figs 27, 28)

Figure 27. The immersive room at the FLV in which we sat on poofs, listened to opera music and watched the cavalcade of Hockney’s Opera designs unfold around us. Sublime? You Bet!

Figure 28. Another opera arrives!

As we listened to the music and watched the cavalcade of the 11 operas Hockney created during the 17 years for which he created stage sets, scenery, costumes and posters move around us, we hear Hockney discussing his experiences designing for the opera. Three things stuck out in my mind. The opera doesn’t pay very well. Collaborating means compromising and he doesn’t much like compromising. And this: “We need more of the opera. It is bigger than life.” As I heard that, I was reminded of the first opera I saw in Paris after I moved here. It was at the gorgeous Opera Garnier. I had a box seat, which was also gorgeous. The opera’s scenery was minimalist, no make that stark, singers wore white sheets as they sang in front of a metal frame. There should have been warnings about the sole source of visual interest, the incessant flashing probe lights. After a few minutes, I fainted and missed the entire thing. Thanks goodness.

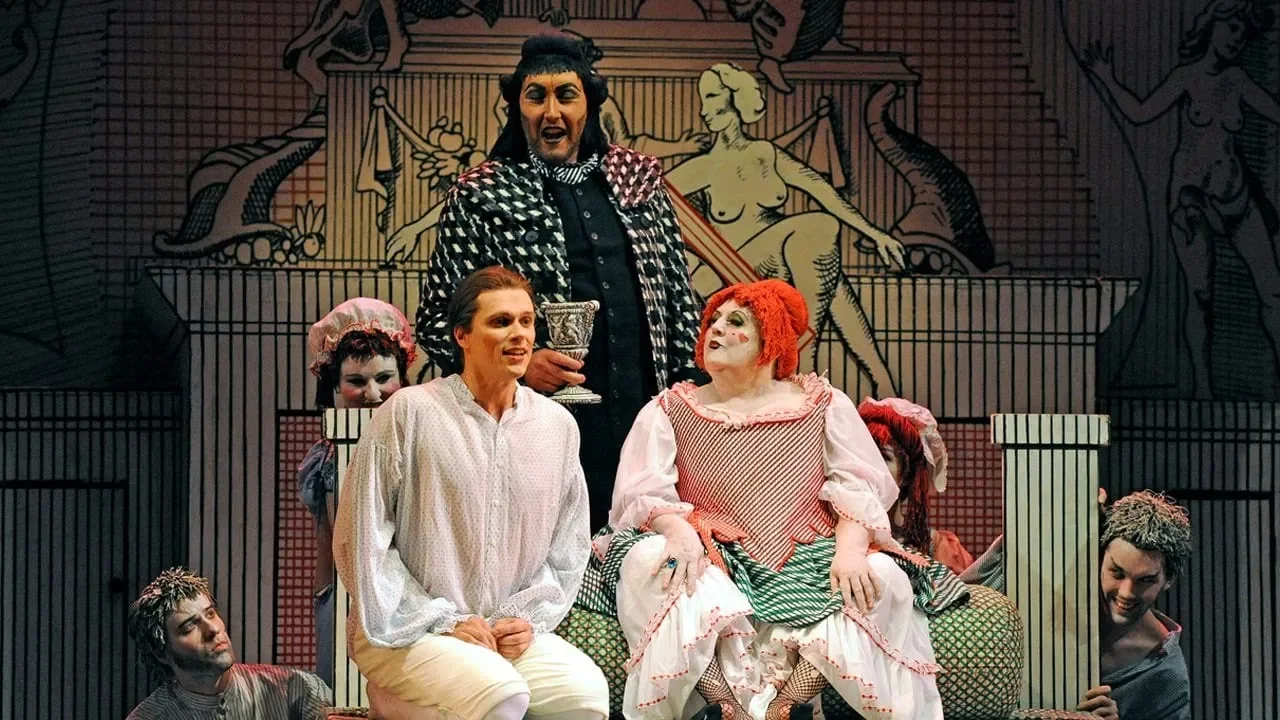

In 1975, Hockney received his first commission from the Glyndebourne Festival Opera to design the stage sets and costumes for The Rake's Progress. Igor Stravinsky, who wrote the opera was, had been, like Hockney, inspired by Hogarth. Hockney’s decision to base his work on Hogarth’s engraved version of A Rake’s Progress was a brilliant one - especially his use of engraving techniques like cross-hatching and parallel lines. With its muted color palette, it’s like watching Hogarth’s engravings come to life. Hockney said: “The Rake’s Progress came at a good time for me because it was a period when I was trying to figure out what to do in painting. So when this came along in 1974 it ended something for me and took me into something else.” In her review of an exhibition on Hockney’s stage sets ( Walker Art Center, 1984) Sarah Fox Pitt wrote (Artforum, April 1984) that “no single artist has made such an impact on the world of the stage since the productions of Sergei Diaghilev and Les Ballets Russes.” (Figs 29-30). Hockney went on to design the sets, costumes and posters for 11 operas during the next 17 years.

Figure 29. A Rake’s Progress, Hockney’s first opera design, stage set

Figure 30. A Rake’s Progress, Hockney’s first opera design

The exhibition in 1984 was called Hockney Paints the Stage, and that’s the title of this portion of this massive exhibition, too. Jonathan Jones summed up the experience of being in the opera room this way, “(Y)ou realize how deep and sustaining a love for life this man feels and can communicate…I had tears in my eyes. Life is a dream, I finally understood, and Hockney dreams it well.”

I was moved to tears too by the generosity and abundance of this exhibition. It definitely is what the world needs now, especially now. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Thanks to everyone who sent a Comment, they are much, much appreciated.

New comment on “I have this urge, this compulsion, to share my enjoyment…” Ma Normandie. :

Dear Beverly,

You have opened my eyes to David Hockney after reading the current and previous postings. Although I knew his name, remember seeing at the de Young in San Francisco his The Bigger Exhibition, 2014, your many descriptions and interpretations of his work has been a wonderful discovery. This is true also of all I read about the Bayeux Tapestry which I saw many years ago in Normandy.

I now wish I had made time while I was in Paris recently to see the show at the FLV. I did catch online under the CULTURE THING a detailed view of it, however.

Sad to learn about Hockney's declining health. "Do remember they can't cancel spring."

Susanne

Great posting, and Hockney’s works glow like jewels. Thank you for bringing them to our attention. As for the female figure in the Bayeux Tapestry identified therein as Aelfgyva, she is not being punched but is having her face fondled, an image connoting sexuality and sexual harassment – see for example the twelfth-century Herod and Salome capital at the Musée des Augustins, Toulouse, reproduced here: https://www.wga.hu/html_m/zgothic/1romanes/cap-12c1/09f_1101.html Diane Wolfthal’s Images of Rape: The “Heroic” Tradition and Its Alternatives (Cambridge, 1999) discusses that motif among others, while M. W. Campbell discusses the likely candidates in his article “Aelfgyva : The Mysterious Lady of the Bayeux Tapestry,” able to be read here (although the mystery remains) https://www.persee.fr/docannor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_2_5553

Continue your fine work (and comments on contemporary events) – they make my Sunday afternoons! Lorraine, Worcester MA

Dear Lorraine, Thanks SO much for this treasure trove of information. I’m off to Bayeux soon and will look at this scene with much better informed eyes. Beverly

Dear Beverly, I just read today’s Musings and am bursting to tell you how much I loved reading and SEEING your blog. I had cataract surgery Thursday and it is the first astonishing look at how the world might be brightening (at least for me). I love Hockney but was gobsmacked, knocked out, almost turned into an optimist by his vision of a place where anyone would be happy to live. Perhaps the last time I felt that way was sitting in the middle of a room at the de Young surrounded by his video of the changing seasons in Yorkshire. I went back a few times because I couldn’t get enough in only one long viewing. (I’d still be returning if only it were a permanent installation.) Melinda, S.F. & Paris

Beverly,This is wonderful. You've captured the beauty of Hockney's work, and the pleasure of the changing seasons, and the delight of being in France.Kaaren.

Thank you for this, Beverly! I love reading about Hockney and seeing his work through your sharing it with us. AND I love seeing your photos showing the likeness between Ma Normandie and Petit Rousset. I have never been to the one and have fond memories of the other. Plus, of course, Hockney's homage to Monet - wonderful! Sydney, Portland, OR

Thank you for another rich post Beverly. There's always something to learn ans you celebrate the riches so beautifully. Kathy, Oxford, England

Thank you Dr B! Your writing runs around in beautiful, distinct cycles just like the seasons too! Anne. Sydney Australia

Excellent piece and extra credit for the Perigord inclusion.Martin, Perigord

Hi, Dr. B — I saw the Hockney exhibition at the Vuitton Foundation and have always enjoyed seeing the Bayeaux Tapestry. Also recently saw a program on Youtube about Hockney's long-standing interest in optics and the Hockney-Falco theory. Have long enjoyed much of Hockney's work but your two recent columns have helped me to understand and appreciate his body of work much more. They, plus the program about his interest in optics as used in painting during the Renaissance, have also enabled me to embrace Hockney's use of technology (that I-pad), at least to some extent. Thanks again for your column. Peg