The Little Gallerist Who Could

Berthe Weill at the Musée de l’Orangerie

Ginevra enjoying herself in front of a painting by Raoul Dufy, 30 ans ou la Vie en rose, 1931

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week: one of the exhibitions Ginevra and I saw before she returned to San Francisco, where I’m headed. As I write this, the government shutdown and the FAA reduction of air traffic doesn’t affect international flights - unless of course there’s no flight controllers at the airports helping pilots land!

The exhibition that is at the Musée de l’Orangerie until the end of January was one that I was particularly looking forward to seeing. On the gallerist Berthe Weill. I wrote about Weill in March, 2021. I called my piece, ‘A Little Gallerist with Big Ideas and subtitled it, Berthe Weill and Avant-Garde Art:.’ My subtitle is the title of this exhibition.

When I wrote about Weill that first time, it wasn’t in connection with an exhibition. The pandemic had begun a year earlier and museums were still closed. I was writing about the artists and collectors and gallerists who made Paris their home. And because of whose largesse (and France’s draconian death taxes) the country, especially its capitol, has so many museums. I first learned of Weill because her name kept popping up in conjunction with artists like Picasso, Modigliani, Diego Rivera.

Ginevra at the entrance to the Berthe Weill exhibition, Musée de l’Orangerie

Here’s how I happened to write about Weill. I was talking with Camille Roux dit Buisson, Director of the Jacqueline Marval Committee. We were discussing the article I was writing about Jacqueline Marval. And I mentioned my interest in Berthe Weill. She put me in touch with Marianne Le Morvan, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Weill. And then, clever woman, simultaneously found her calling and a job - founding director of the Berthe Weill Archives. She’s the co-curator of this exhibition at the Orangerie, which opened first at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Montreal, then moved to the Gray Gallery at New York University before coming to Paris, to the place where it happened. I spoke to Marianne when I began doing research for my article on Weill. As my research progressed, she graciously answered my questions. She even reviewed my article before I sent it out into the ethers. I corrected or clarified most of the points she raised.

For example, I suggested that the business partnership Weill had with the Spanish art dealer, Père Manach, (a friend of Picasso’s) may have ended so abruptly because a jealous wife at home in Spain insisted that Manach return. Marianne told me that I was pursuing a false line of inquiry. Weill did not fancy men. I left it in anyhow. I later learned that Manǎch was labeled an anarchist by the French authorities and that’s probably why he left France so abruptly.

I also wrote that Gertrude Stein waited to buy paintings by Matisse until he had left Berthe Weill’s gallery because she didn’t like Berthe Weill. I speculated that it was because they were both short, strong willed, Jewish women. Turns out they had something else in common, they were both lesbians. Maybe Weill had rejected Stein’s advances or maybe they were both in love with the same woman, Alice, perhaps.

Weill’s antagonisms with Stein and her friendship with Picasso fed into the narrative that I was developing in my head about both of them. As I learn more about Stein, I liked her less. What’s there to like about someone who translates Nazi propaganda into English for her German officer friend so that she and Alice could stay in Paris. She did this as Nazis rounded up Jews, artists and collectors and gallerists among them, and deported them to concentration camps.

As I learned more about Picasso’s personal life and I mean more than his misogynistic tendencies, I began to appreciate him. Even though he was a person of interest to the French authorities throughout the war and could have deported to Spain where he surely would have been murdered by Franco, he tried to help his Jewish friends like Otto Freundlich and Max Jacob avoid the Nazis. Perhaps that’s why, I credited him with organizing an auction after World War II, of work by artists, like himself, who had been championed by Berthe Weill. The proceeds from which enabled Weill, destitute after the war, to live out her old age in dignity. The exhibition talks about a committee that was arranged to hold the auction, Picasso wasn’t mentioned. And as I reread my own article, I see that I didn’t propose it either. I must have read it it elsewhere, maybe in conjunction with the exhibition on Picasso that was held at the Musée d’Immigration a while later. I’ll have to check.

But then, It was only when I was at this exhibition that I began to wonder where and how Weill had lived, in hiding, in Paris, during the Nazi Occupation. The curators clearly state that Weill laid low in Émilie Charmy’s studio. I assumed that meant that Charmy and Weill were a couple. But, unless Charmy was bi-sexual or became a lesbian after she married and gave birth to her son, I don’t know, well at least I don’t know yet.

This exhibition, like the Paul Poiret exhibition at the Musée des Arts Decoratif, and the exhibition I saw at the Bibliotheque National de France just before I left Paris, on the writer, Colette, features paintings by the female artists that Weill championed. Weill, it turns out, was a champion of women artists. Like Jacqueline Marval (about whom I have written here) and Suzanne Valadon (about whom I have written here) and Marie Laurencin, whose name most French people of a certain age know because of a song that was popular during the 1970s which mentions her name. And whose name I know because she was Apollinaire’s muse and lover. And Émilie Charmy, whose works I think I first began to take serious notice of at an exhibition about Modigliani that I saw at the Barberini Museum in Potsdam, Germany last year. And now, she has been popping up in all the exhibitions I have been seeing. While I’m in San Francisco, experiencing withdrawal symptoms from the museums and galleries that keep me going when I’m in Paris, I will have to learn more about Émilie Charmy - her life and her art. And of course, share it with you!

The exhibition at the Orangerie is filled with paintings by the artists whose works Weill championed, portraits and caricatures of Weill by those and other artists, gallery programs for the exhibitions held at her gallery, archival photographs of her studio and the events that that took place there. Scattered throughout are quotations from Weill’s 1933 autobiography, entitled, Pan!…dans l’oeil.. (“Pow… right in the eye) The subtitle is:. “… or thirty years behind the scenes of contemporary painting 1900-1930”.

Actually, I’ll tell you about the exhibition next time. Your homework this week is to read the article I wrote about Weill almost six years ago. So that we’re all on the same page for the next article. To whet your appetite, here are a few of the paintings I just saw at the Berthe Weill exhibition in Paris. (Figs 1-6) And here is the link to A Little Gallerist with Big Ideas: Berthe Weill. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

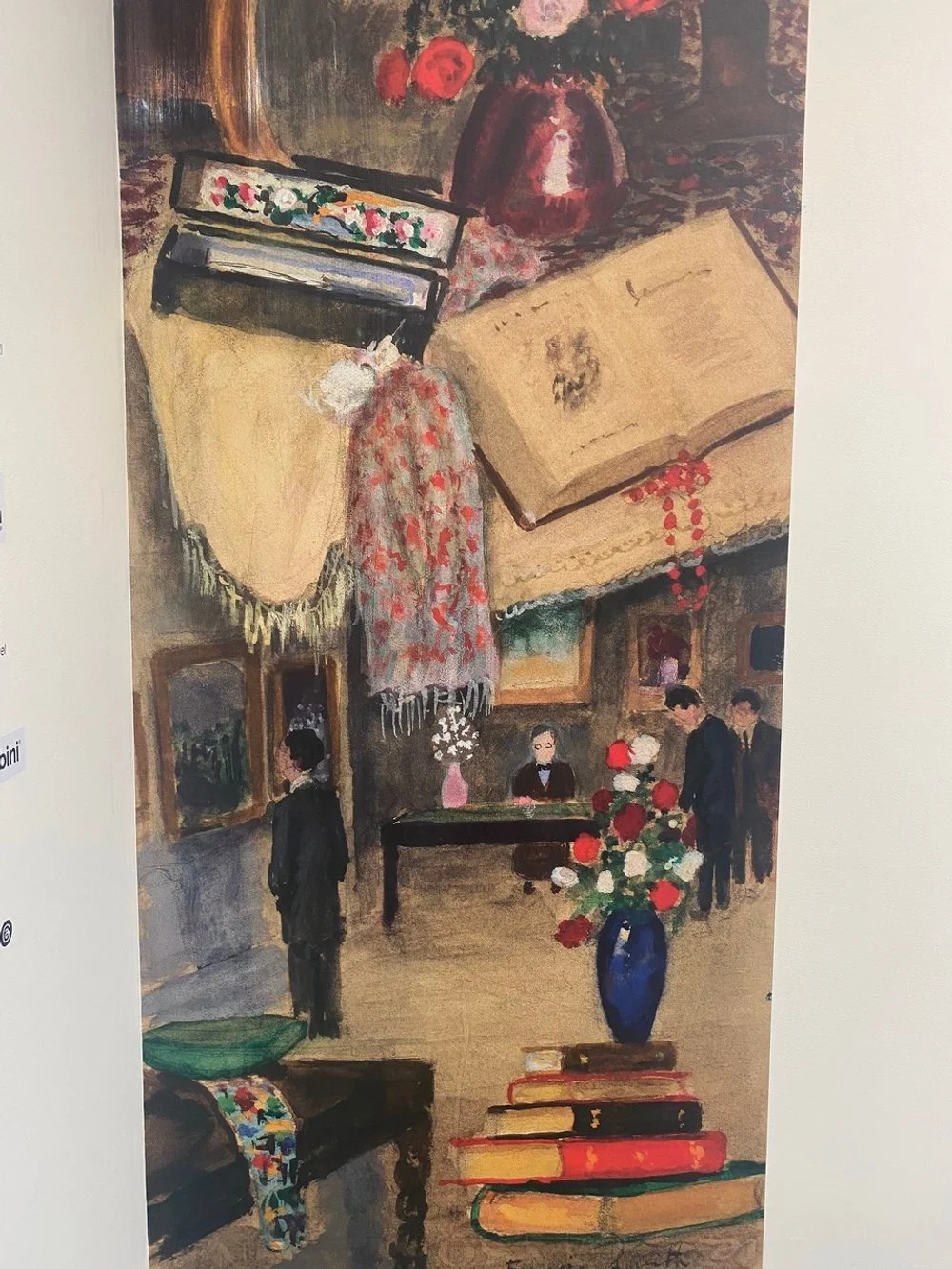

Figure 1. Detail of painting in Berthe Weill’s gallery, she is the tiny figure in black seated at the back

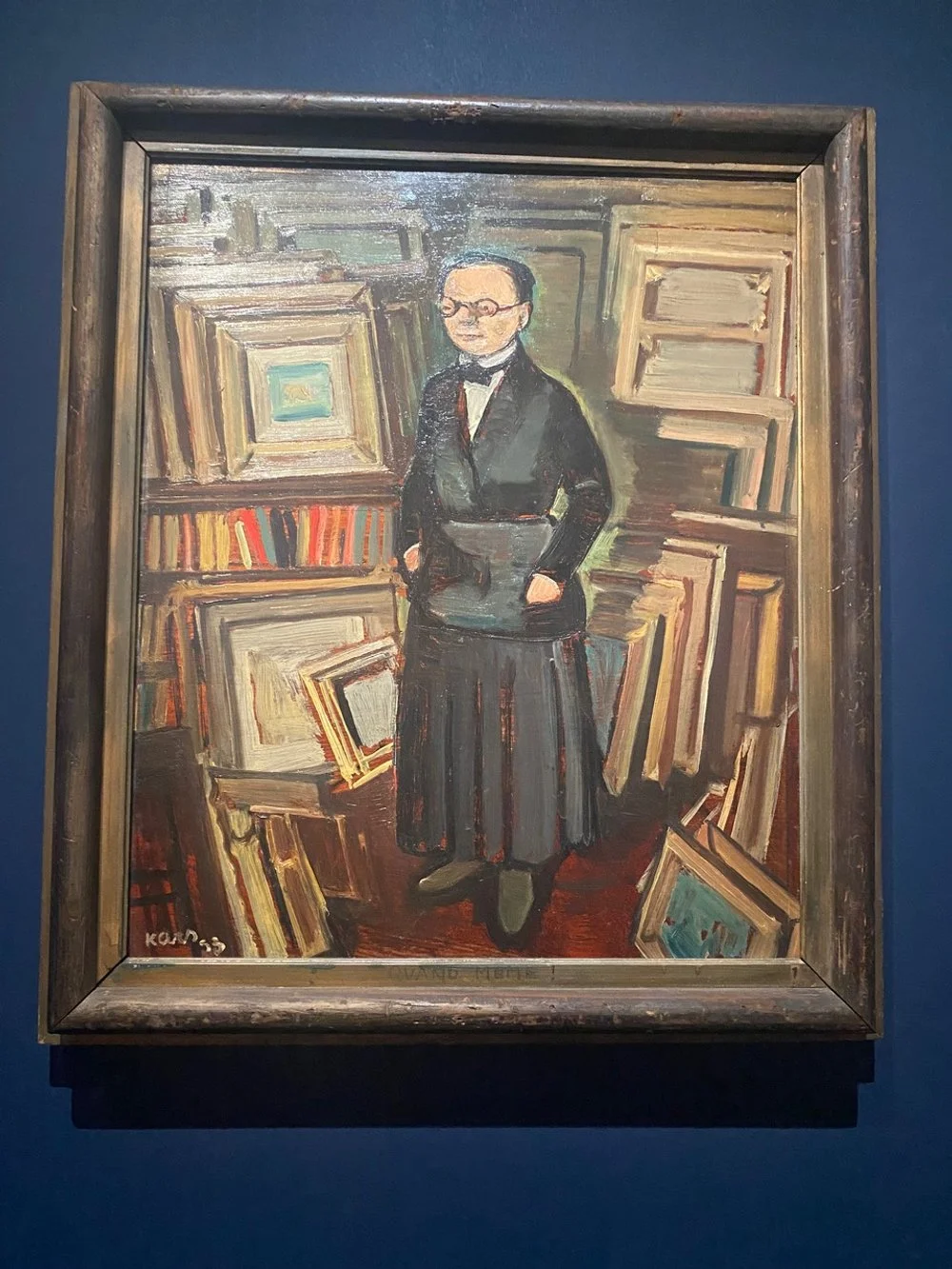

Figure 2. Berthe Weill, Georges Kars, 1933

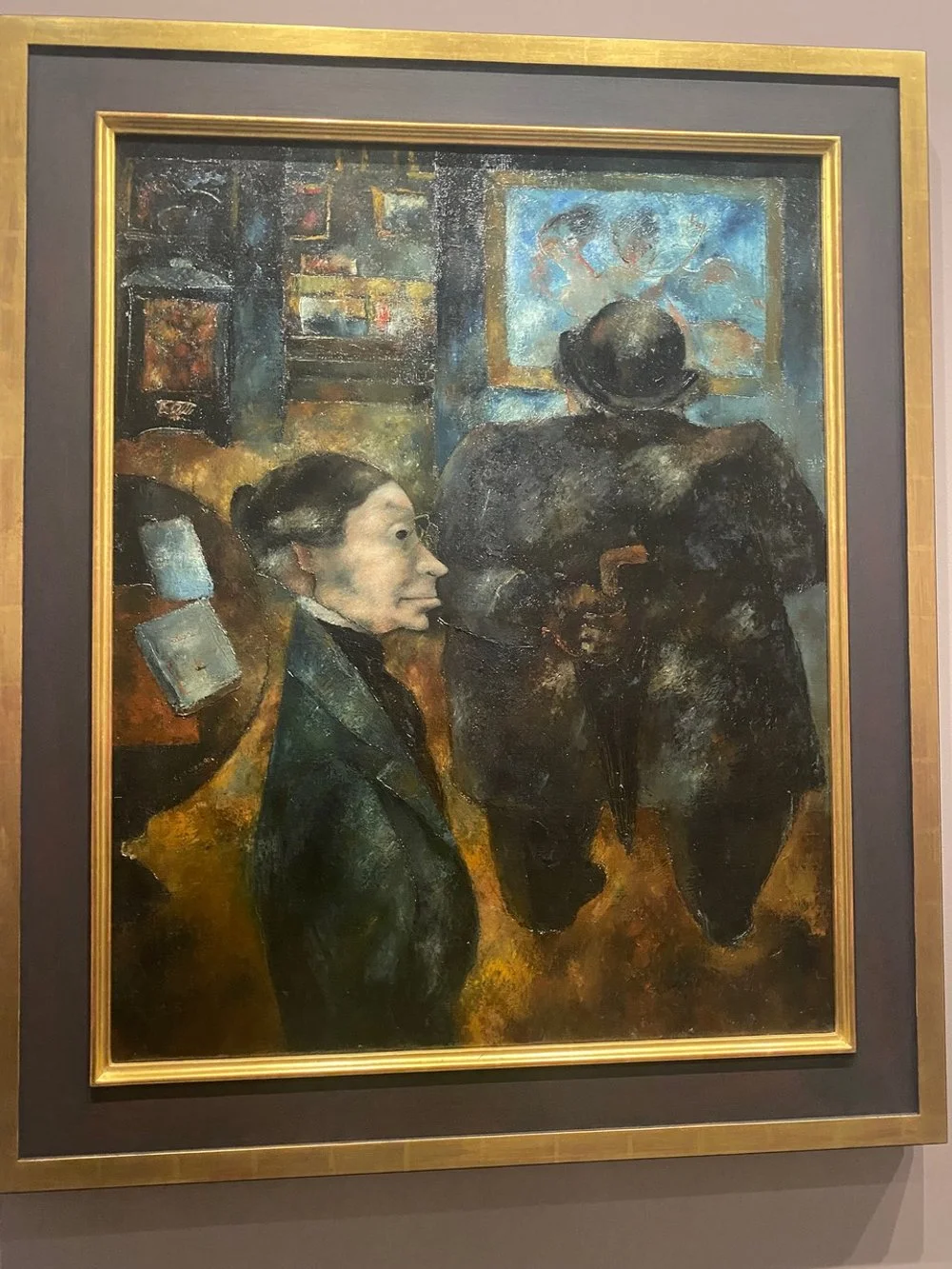

Figure 3. Berthe Weill, Edouard Goerg, 1926

Figure 4. Berthe Weill, Émilie Charmy, 1910-14

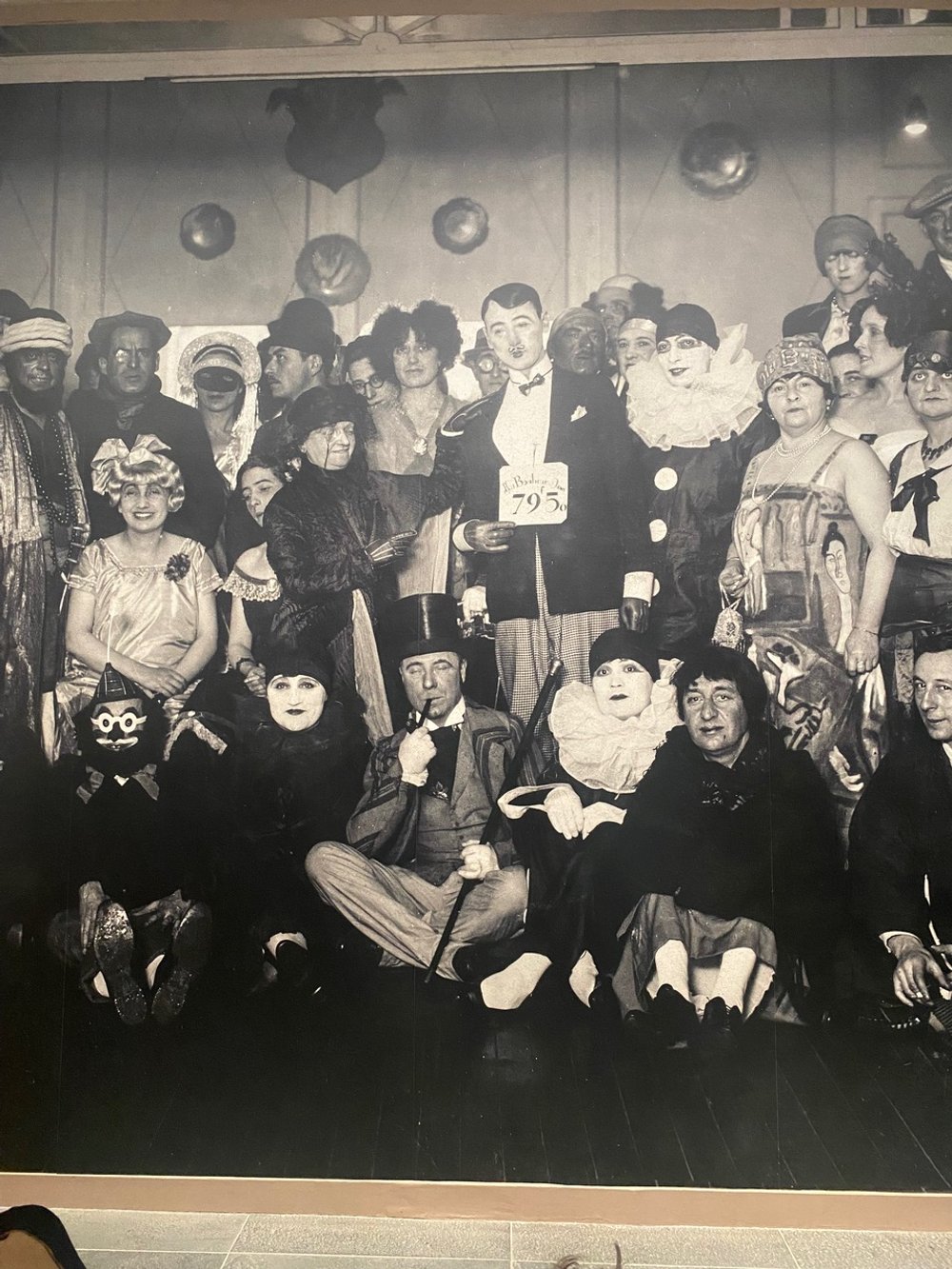

Figure 5. Costume Party at Berthe Weill gallery. She is the only one not dressed up!

Figure 6. Weill’s autobiography, published in 1933

And here is the link to A Little Gallerist with Big Ideas: Berthe Weill. (again, just in case :)