On top of Auld Reekie, Part II

Georgian Edinburgh

We’re back in Edinburgh this week. And I think Ginevra and I will be returning to Edinburgh soon. It is the perfect mix of culture and nature. It’s a good place to be. Like the people we met along the West Highland Way, the people we met in Edinburgh (and Glasgow) were welcoming. And unlike most of the meals we ate along the Way (and in Glasgow) the meals we ate (and ingredients we bought) in Edinburgh were delicious!

Our second day in Edinburgh was a full one. After immersing ourselves in Old Town the first day, Ginevra wanted to concentrate on New Town, aka Georgian, Edinburgh. Calling buildings that date from the middle ages to the 17th century ‘Old Town’ seems right. Calling the 18th century buildings that make up the next wave of planning and construction, the New Town, is, for an American, delightful. I came across the idea that buildings from the 18th century could be called New when I first visited Rocamadour, in the south of France. It tickled me then and it tickles me still.

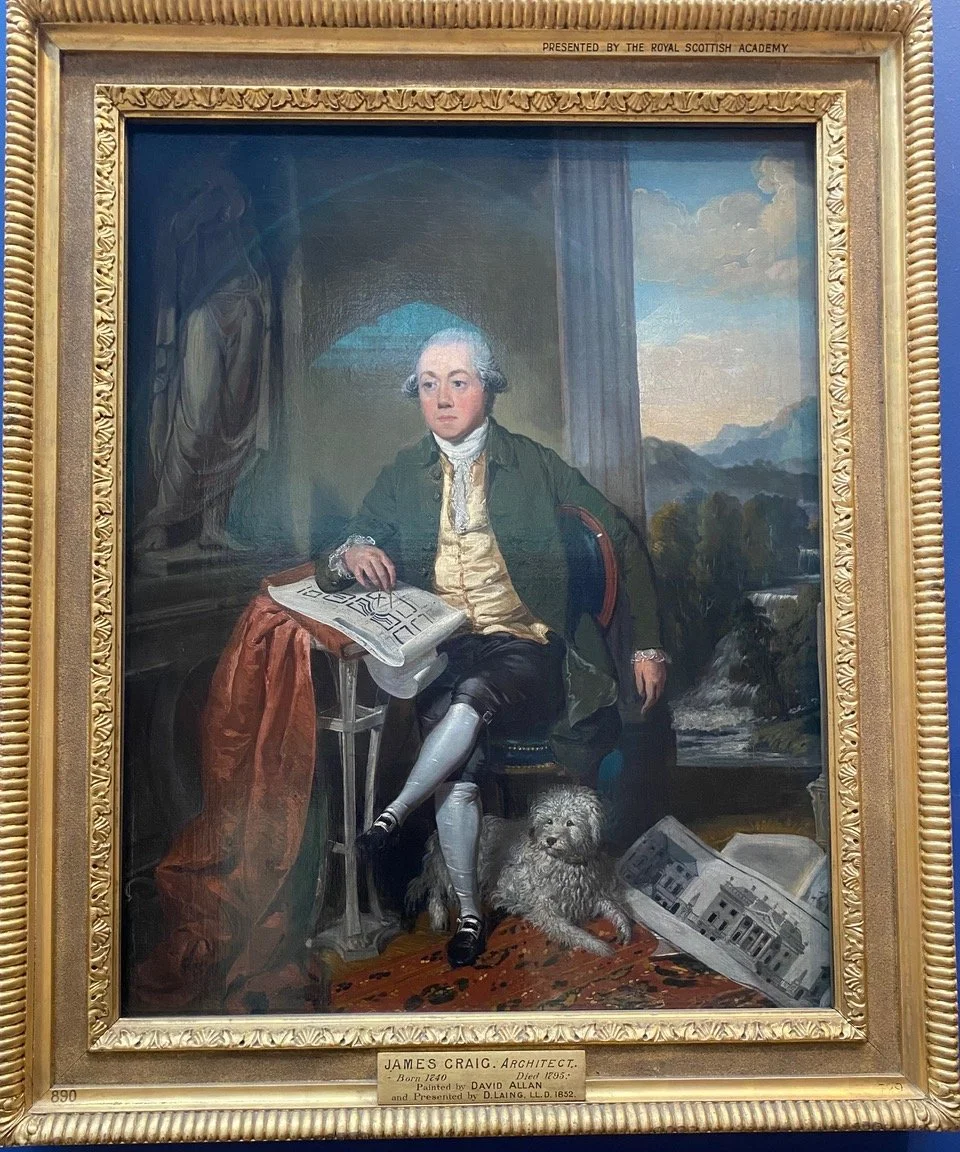

Here’s how Georgian Edinburgh came into being. By the mid-18th century, Edinburgh was extremely overcrowded. Everyone - rich and poor and middling alike - lived in the densely populated tenements of Old Town. In 1766, a young, unknown architect named James Craig won the competition to design a layout for Edinburgh's first New Town. It was intended as a residential development for wealthy people only. A place where they could escape the squalor of Old Town. Craig's design was a grid plan. Grid plans have been around for centuries. The Romans standardized it. Philadelphia was built on a grid plan in the 17th century and the planned town of Washington, D.C. is a grid plan from the following century. Grid plans can be pretty boring, at least until the towns grow into themselves, which when I lived in Canberra, Australia, hadn’t happened yet.

Craig’s design included gated gardens. Of course it did, how else to keep the riffraff out. One year, Ginevra attended a masters program on historic preservation in London. The building where classes were held faced a gated garden. How fun it was to get the key and have lunch in a (more or less) private garden.

Craig's grid worked but his designs for the facades of buildings didn’t. Critics complained that the buildings were too plain, that they lacked architectural interest. So in 1791, Scotland’s foremost architect, Robert Adam came to the rescue. He drew up elevations for Charlotte Square giving New Town some grandeur and elegance. The first houses were ready for occupants by the mid-1790s. One of the houses, 7 Charlotte Square, is now a museum operated by the National Trust for Scotland. Called Georgian House (not too inventive), it was obviously the place to start our day - poking into the lives of the rich and the lot of their servants in 18th and early 19th century Edinburgh.

The first occupant of Georgian House was John Lamont who bought the mansion in 1796 as an in-town residence for his family to stay during the social season. As the eldest son, Lamont had inherited a title and an estate, the rents from which were his main source of income. Along with title and estate, Lamont inherited debt. Which didn’t stop him from living beyond his means and accruing more debt. (Let the next generation worry about it, I can hear him saying to himself and anyone who would listen.) Alas, his debts caught up with him before his death did and he was forced to sell this house and move back to his estate in 1815. He died a year later.

The fifth and final private owner of No. 7 Charlotte Square was the Marquess of Bute. The 4th marquess owned Nos. 5 and 6 when he bought No. 7. With this purchase, the entire middle section of Robert Adam's 'palace front' design became his. He talked the owners of the properties on either side of his to restore their facades as he was doing. To strip away as much of the Victorian additions as possible, to make the facades look as much like Adam's original design as possible. At the death of the 5th Marquess of Bute in 1956, his successor was obliged to use the three adjoining mansions as partial death duty payments. Which is how the National Trust for Scotland became the owner.

The entire property, all five floors, was rented out when the National Trust took it over. The basement, ground floor and first floors to one occupant, the second and third floors to another. The basement, ground floor and first floor were vacated first. And those three floors have been restored to reflect how the Lamont family and the next family, and their servants lived from 1760 to 1830. Most of the furnishings and fittings date from that period. The second and third floors have only recently been vacated and they are, at least for now, mostly empty. There was a film on the second floor, about New Town and what life was like for those lucky enough to live here and those who found employment here around the year 1810. At one moment in the film, a maid opens a window, shouts something and then empties a pot onto the street below. Was it cooking water, bath water? Actually no, she emptied a chamber pot onto the street. And what she shouted was, “Gardez l'eau!” (In FRENCH) to, as my source notes, “warn pedestrians of the impending urine shower.”

After watching the film, we walked downstairs to the first floor, to the Drawing Room and Parlor. There are no guided tours but there are guides in each room who can answer your questions and give you insights you didn’t know you needed. As you will see in a moment. The Drawing Room is at the front of the house overlooking Charlotte Square. It is the full width of the house and would have been where the family entertained large groups. Behind the Drawing Room is the Parlor where the family gathered more casually. And where tea would have been served. The walls are the same color in both rooms so that on evenings when both rooms were filled with guests, they would have made a harmonious whole.

There are two rooms on the Ground Floor, too. The Dining Room is at the front of the house, the street side. The Master Bedroom is at the rear of the house, just below the Parlor and just above the kitchen. The occupants of the master bedroom were assured a good night sleep - removed from the noise of the street and warmed by the stove in the kitchen below. Who cares if the children froze to death on the second floor. (Figs 1-8)

Figure 1. Grid Plan, New Town, Edinburgh, James Craig, 1766

Figure 2. Georgian Edinburgh

Figure 3. Georgian House Facade, 7 Charlotte Square

Figure 4. Drawing Room, Georgian House

Figure 5. Parlor, Georgian House

Figure 6. Bedroom, Georgian House

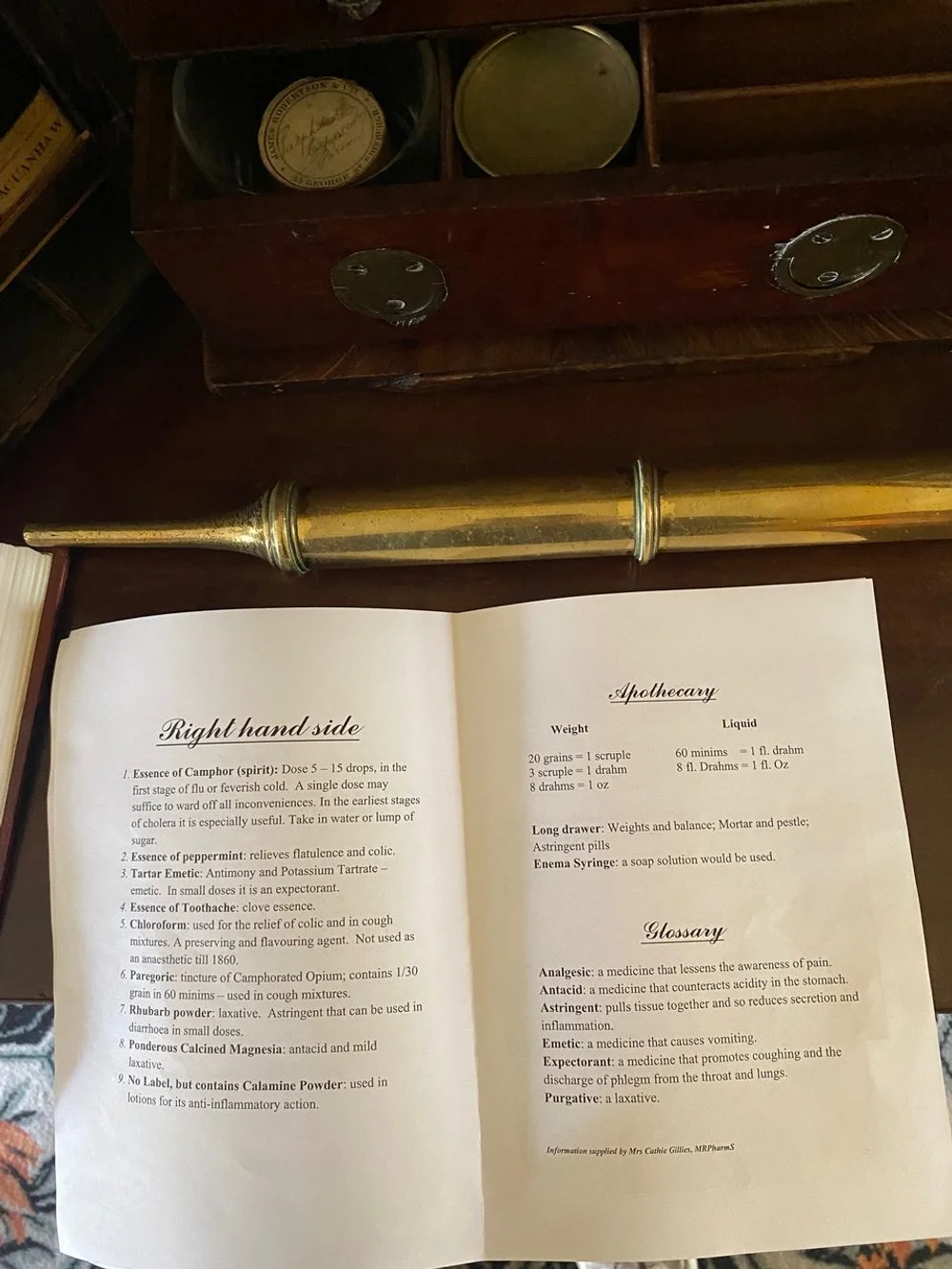

Figure 7. Medicine Chest, Georgian House

Figure 8. For the chemist of the house, Georgian House

But it wasn’t the dining room or master bedroom that interested me on the ground floor but the narrow passageway between the two. In that space was a flushing toilet installed around 1805. The room guide explained that after dinner, when the women adjourned, the men would sit around the table and smoke and drink. And when the need to relieve themselves arose, they would simply get up, walk over to the porcelain basin and pee. And sometimes they would continue talking while they peed. And what did the women do if they had to pee, I asked.They simply walked over to the basin, sat down and peed. During dinner.

As I listened to the guide, I was reminded of my visit this past summer to the Chateau de Vandeuvre in Normandie. I was there for the gardens but since a few rooms in the chateau were open to visitors, I checked them out, too. In the bedroom, tons of stuff were on display, a few items were described. One of the items was a covered porcelain vessel which looked like a gravy boat, which seemed a strange thing to have in a bedroom. And then I read a description of the vessel’s actual purpose. Called a Bourdaloue, it was named after Louis Bourdaloue (1632-1704), a priest whose oratorical skills were such that nobody wanted to miss a single word of his sermons. Even to go to the bathroom. And since he was so long winded, that sometimes happened. And when it did, the female congregants were prepared. They had bourdaloues under their dresses, so they could relieve themselves without missing a word. As one source notes, these ‘porta potties’ “were ergonomically designed to accommodate the female body. A slightly raised lip at one end and a handle at the other allowed the woman to relieve herself from a squatting or standing position.“ So, I hear you asking, did a woman just sit there with a pot full of pee between her legs. No, of course not. Her maid would come and take the pee pot from her mistress and empty it. And presumably return it discretely, it might be needed again. Did the woman pee as she sat in her pew, or did she move to a more discrete place in the church, Nobody seems to know. However, another source suggests that the word ‘loo’ might be an abbreviation of Bourdaloue. Bourdaloues were used throughout the 18th and for most of the 19th century. When water closets became common features in homes, starting with the homes of the wealthiest, of course, chamber pots were put away or another use was found for them (gravy boats maybe?). (Figs 9-13)

Figure 9. Passage Way Toilet, Georgian House, Edinburgh

Figure 10. Apres-Diner des Anglais..(The man on the left is missing the target) French, 1814

Figure 11. Bourdaloue, chamber pots, (Sevres, Meissener and others, 18th century

Figure 12. La Toilette intime (Une Femme qui pisse), Francois Boucher, 1760.

Figure 13. Bourdaloue with a lid but without a head, 18th century

All of which got me to thinking about where and how people relieved themselves over the centuries. Privacy and modesty are relatively recent requirements, it seems. As I read more, I saw more images - of group toilets and the ubiquitous pissoirs that used to dot the streets of Paris and which have now made a comeback, although a little more discretely. Urinals, I learned, came to Paris in 1839, when Claude-Philibert de Rambuteau was Préfet de la Seine (and thus de facto mayor of Paris). By 1843 the city had over 400 “colonnes Rambuteau” as Parisians called them. Not surprisingly, Rambuteau was not pleased with having his name associated with a pissoir so he started calling them “colonne vespasienne,” a reference to the Roman emperor Vespasian who, in the 70s A.D. had clay pots dispersed around the city to be used as urinals. People call the urinals in Paris lots of things but they don’t call them Rambuteau (although there is a street in the Marais that is named after him). Too bad the préfet who followed Rambuteau by some 50 years, Eugène Poubelle, didn’t try harder to keep his name from being associated with the public convenience he introduced to Paris and all of France - garbage cans. I guess the same can be said for Thomas Crapper and flush toilets. (Figs 14-16)

Figure 14. A group toilet in ancient city of Ephesus, Turkey

Figure 15. Colonne Rambuteau. Apparently when men first began to use them, they peed on the sides, rather than inside, following the tradition of male dogs, rather than common sense

Figure 16. A newer version, called Colonne Vespasienne

At the Georgian House, the kitchen is what you would expect. It’s at the rear and has an adjoining scullery. There’s also a servants room, wine cellar and china closet, the latter two of which were locked and only the housekeeper had a key. In one dark passage (no reason to waste candles on staff) is a long strip of the bells which would have been connected via wires throughout the property to summon servants to wherever and to whomever they were needed (to empty a chamber pot, perhaps). (Figs 17-18)

Figure 17. Kitchen, Georgian House, Edinburgh

Figure 18. Bells to ring the servants, Georgian House, Edinburgh

We worked up quite an appetite touring and conveniently, it was time for lunch. Ginevra wanted to eat at Dishoom, a restaurant she remembered fondly from living in London. But at 2:00, the line was long and we were too hungry to wait. We ate at the nearby Wagamama, another restaurant from Ginevra’s London days. It was a good choice. Generous portions, excellent taste, professional service.

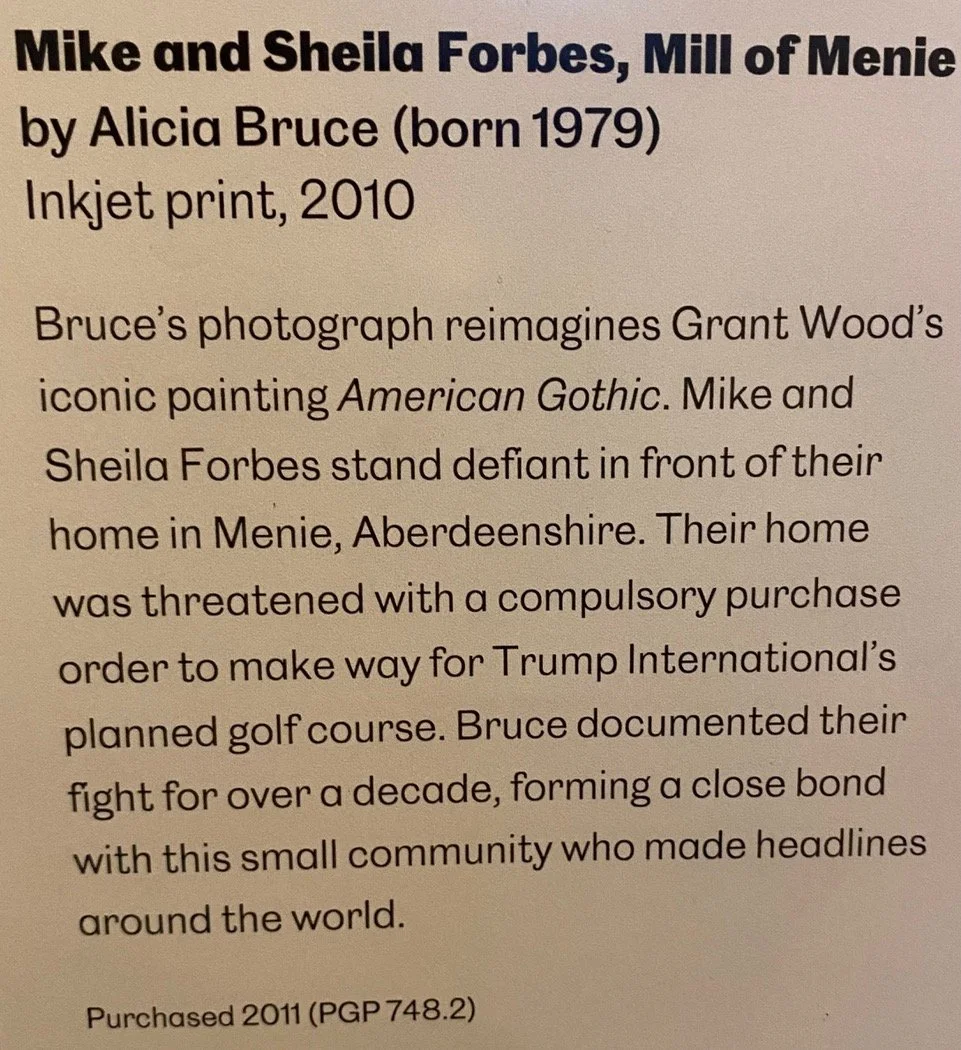

After lunch we walked over to the National Portrait Gallery and saw some of the people we had learned about at the Georgian House, like James Adam, Robert Adam’s brother and James Craig. The portraits are arranged chronologically and thematically and provide an excellent introduction to Scottish history. As we were chatting with one of the guards, and once she confirmed that we didn’t have MAGA sympathies (the tip off was us inquiring about the Mapplethorpe Gallery), she told us to be on the lookout for a photograph of the couple who had refused to sell their land to Trump International. We found the photograph and enjoyed reading about the couple. Without her telling us to look for it, we probably would have missed it. (Figs 19-24)

Figure 19. James Craig, architect who designed New Town when he was young and unknown

Figure 20. James Adam, Robert Adam’s brother, part of the architectural dynasty.

Figure 21. Fourth Earl of Dunmore by Joshua Reynolds

Figure 22. Earl of Eglinton, John Singleton Copley (American artist). (Notice matching socks with fig. 19)

Figure 23. Couple who refused to sell their land to Trump International.

23a. Text for the photograph

Figure 24. American Gothic, painting by Grant Wood (1930) upon which Fig 21 based

On our third and final day in Edinburgh, we first went to the boulangerie on Portobello High Street that we had walked by every evening after it had closed. Twelve Triangles was worth starting our day a little later. We bought a baguette and a tart and two very plump scones. I noticed cheese in the fridge from I J Melles, the cheese shop where we bought cheese our first day in Edinburgh, so we bought a piece of cheddar, too.

When we got to Edinburgh, our first stop was the Scottish National Gallery. We were interested in the permanent collection because it always seems that any temporary exhibition we go to, one or more paintings will be on loan from the National Gallery of Scotland. We were expecting to see major masterpieces by major artists and we did. And we saw paintings by (mostly unknown to us) Scottish artists, too. (Figs 25-30)

Figure 25. Twelve Triangles, Boulangerie and Patisserie in Portobello, Edinburgh

Figure 26. Three Graces with paintings by Reynolds and Gainsborough on left, National Gallery, Edinburgh

Figure 27. Ladies Waldegrave, Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1780, National Gallery, Edinburgh

Figure 28. Skating Minister, Henry Raeburn, 1795, National Gallery, Edinburgh

Figure 29. Lady Agnew, John Singer Sargent, National Gallery, Edinburgh

Figure 30. Lord Ribbesdale, John Singer Sargent, National Gallery, Edinburgh

And then we went to lunch. To Dishoom where, as their website says, “you’ll find the food of all Bombay – its cafés, grills, street stalls, homes and everything delicious in between.” We ate a wonderful mix of beautifully fresh and well prepared food. I didn’t really fall in love with Indian food until we lived in Australia. There are tons of restaurants serving Indian food. And when people invited us over for dinner, they often prepared Indian meals. When we first got back to San Francisco, I continued making Indian food. But it’s labor intensive, there’s a lot of cutting and chopping. You really need a staff for that kind of cooking. And I didn’t have one. As we ate at Dishoom, I realized how much I miss eating good Indian food. (Figs 31, 32)

Figure 31. Ginevra getting ready to eat at Dishoom, Edinburgh

Figure 32. Not any longer. Everything was delicious. Dishoom, Edinburgh

After lunch, as we walked along the mostly uniform facades of Georgian Edinburgh, we happened upon Stockbridge. Which was built in the early 1800s as stables and carriage houses for the nearby grand homes of New Town. The main road through Stockbridge, Raeburn Place, named after the Scottish painter, Henry Raeburn, has lots of small shops, among them Rare Birds, a book shop that sells books written by women. Ginevra bought Persuasion, the only Jane Austen novel that she didn’t already own. On a nearby street was an outpost of I J Melles cheese shop, so we bought a bit more of the blue cheese we had liked so much the first day. We wandered along cobbled lanes with terraced houses overflowing with flowers and ivy. We happened upon a private garden where a woman was holding open the door and people were walking in. So we went in, too. After a while, we realized that without a key, we couldn’t get out. Even after all the challenges of the West Highland Way, I didn’t fancy catapulting over the gate. So Ginevra went off in search of the woman with the key, who graciously let us out! (Figs 33-37)

Figure 33. Ginevra in front of Rare Birds Book Store, Stockbridge, Edinburgh

Figure 34. Ginevra wandering around Stockbridge with her Rare Birds Book Store bag

35. Wedding couple in Stockbridge

Figure 36. Beverly in Gated Garden, Stockbridge

Figure 37. Ginevra and me just before we realized that we couldn’t get out of this beautiful gated garden

You may be familiar with Stockbridge even if you’ve never been there. It’s been used as a location in various films and television dramas, from the Prime of Miss Jean Brody to Rebus. And it’s definitely where we’re staying the next time we’re in Edinburgh which I hope will be soon, Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Thanks to everyone who sent a Comment about last week’s post on Edinburgh. As always your comments are much appreciated.

New comments on On top of Auld Reekie:

Dear Beverly and Ginevra, thanks to you both, Scotland is a dream destination... I love everything you both do with such talent... I can't wait to discover your new adventures… Gérard, Paris

Quite a few years ago when I visited the city with a companion on our brisk tour of

the UK [I had rented a car at the Manchester, UK]. With my Scottish DNA we did tour

the castle and strolled down the Royal Mile. Although I think, based on your walk, that

the retail sector has multiplied dramatically as my recall is that we were disappointed in the Royal Mile. Loved the offerings of the cheese shop….and a French baguette….plus

croissants ! Bill, Ohio

Thank you, Beverly, for reporting your visit to Edinburgh & Portobello. By the look of the bagpipe player, not everything has changed in Edinburgh since I studied divinity in New College 60 years ago! Morris, N. Carolina