The Empire of Sleep

Musée Marmottan-Monet

"To die, to sleep; / To sleep, perchance to dream…; / For in that sleep of death what dreams may come / When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, / Must give us pause” (Hamlet contemplating suicide)

Me with St. Peter Sleeping behind me

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. The exhibition at the Musée Marmottan-Monet (M-M) called Empire of Sleep is one of my favorite kinds of exhibitions. Here’s how you do it. 1. pick a topic, 2. find works of art that relate to that topic. 3. like a game of Gin Rummy or Connections (NYT) connect the images in ways that make sense to you and 4. expound upon those connections with pertinent and (hopefully) fascinating commentary.

Guest curators at art museums are usually art historians. For this exhibition, the guest curator is a neurologist, Laura Bossi. Since the late 1980s, she has been curating museum exhibitions that link art history to the history of science and the history of ideas. For example, a major exhibition she co-curated was at the Musée d’Orsay, (2020-21) “The Origins of the World. The Invention of Nature in the 19th century.” It linked the history of science with the history of art. That year she also curated an exhibition for the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alghieri, author of The Divine Comedy. That exhibition focused on images of Hell from the Middle Ages to present. This time, it’s sleep.

As the introduction to this exhibition notes, although probably unnecessarily, everyone sleeps, even insomniacs. We sleep to survive. And, except for infants and babies (who need a lot more), we should all be spending one third of our lives asleep. Sleeping “is a necessity, but also a great joy.” Some people fall asleep easily while others lie awake unable to sleep, and still others are awakened by troubling dreams, nightmares.

According to the curators, this exhibition, made up of 130 works of art, “explores, for the first time in France, the various representations of sleep and its mysteries, focusing on the long 19th century, from the Enlightenment to the Great War.” Older works are here too, as are works from the 20th century “to demonstrate the extraordinary richness of this subject with its recurring iconographic themes.”

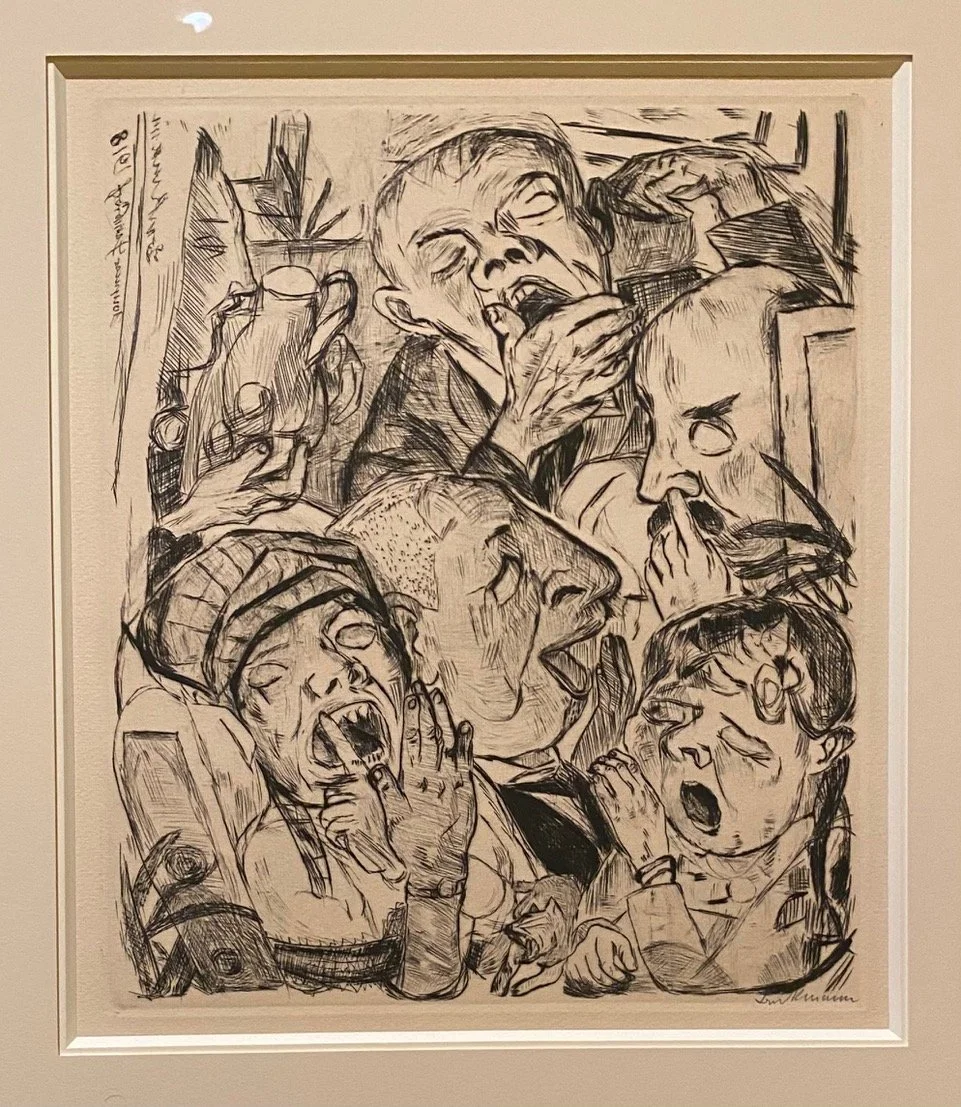

Perhaps this exhibition was the first in France to take sleep as it subject, but as we wandered around trying to stay awake - looking at people sleeping is a bit like watching people yawn, you feel like joining in (Fig 1) - Ginevra reminded me that we had seen an exhibition on Sleep at the National Gallery in London. (Fig 2) For that exhibition, the curators found, mostly in the museum’s own vast collection, 30 paintings of people sleeping. When I got back to San Francisco for Thanksgiving, Ginevra had the little brochure from that exhibition waiting for me. It was nearly 30 years old! We had brought it home with us in 1997, after a summer in the Dordogne followed by a week in London. How it survived is anyone’s guess since I am a purger, not a hoarder and we have moved twice in San Francisco since 1997. The Sleep exhibition at the National Gallery was aimed at encouraging visitors to look at familiar images in new ways. The paintings for the exhibition were divided into 6 themes: death, sloth, vulnerability, peace, dreams and sex.

Figure 1. The Yawners, Max Beckmann, 1918

Fig. 2. Sleep Themes and Variations, 16 July-14 September 1997, The National Gallery, London

The categories for the exhibition at the M-M are a little different and veer towards the scientific, not unexpectedly given the guest curator’s areas of expertise. Among the themes: Innocence of Slumber, Eroticism of Slumber, Boundary between Sleep and Death, Dreams, Nightmares, Sleep Disorders and the Bedroom.

One commentator noted that this exhibition gave the museums to which the M-M appealed for loans, a chance to explore their reserves, to find lesser known paintings by major artists and first rate paintings by lesser known ones that had as their subject, sleep and which could be, without too much trouble, packed up and sent to Paris. One of the joys of this kind of exhibition for both curator and visitor alike, is to see a lot of paintings, some familiar, some not, arranged (sometimes it’s a stretch) around a unifying theme.

The exhibition at the National Gallery said it this way, “Sleeping tends to be done in private and the only people most of us are used to seeing asleep are our families and loved ones. Watching a sleeping person is often an intimate experience and one which conjures up a particular atmosphere of hushed voices and tip toes, of tenderness and vulnerability. Paintings of sleeping figures invite us to look at the sleeper, and often exploit this aura of intimacy.” Or as the M-M curators write, “It is perhaps the sleep of the innocent - newborn babies, children, pets, cats, dogs - which best expresses how we abandon ourselves to the joy of the unconscious. But sleep also displays an ambiguous aspect, evoking death, vulnerability and the dispossession of the self; it forces us to relinquish our vigilance, to accept oblivion, to lower our guard …” (Figs 3, 4)

Figure 3. Nude Woman on a Chair, Felix Vallotton, 1897

Figure 4. Young Girl Sleeping, Bastien-Lepage, 1880

The M-M exhibition begins with Sleep in the Bible. Adam was asleep when God created Eve from one of his ribs. Some anesthesia. Noah on the other hand, fell asleep because he got drunk. He was naked when his sons saw him. Which was embarrassing. Much more troubling was what the daughters of Lot did when their father was asleep. Thinking that they were the only humans alive, they conceived of a way to preserve humanity. They got their father drunk and once he had passed out, they managed to get themselves impregnated by him. No questions please. (Figs 5, 6)

Figure 5. The Drunkeness of Noah, Giovanni Bellini, 1515

Figure 6. Lot and his Daughters, Abraham Bloemaert, 1624

There are lots of depictions of sleep in the New Testament, too. There’s Lazarus who Christ awakened from the dead, the same miracle he performed for the daughter of Jairus. Those images remind the faithful that Christ has the ultimate power over death, that death is nothing more than temporary sleep. John fell asleep during the Last Supper which the curators tell us is “an expression of trust in God.” The apostles who were with Christ as he prayed in the Garden of Gethsemane, kept nodding off. The National Gallery curators contend that this falling asleep was a display weakness, while Matthew, Mark and Luke write that it was a response to sorrow, fatigue and confusion. (Figs 7, 8)

Figure 7. Last Supper with St. John asleep on Christ’s shoulder, Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1480

Figure 8. Agony in the Garden, Andrea Mantegna, 1455

For me, the most poignant images of sleep in the New Testament are those showing the Virgin Mary with the sleeping Christ Child on her lap. On one level, the images speak of a mother’s tender love for her child. More profoundly, the images allude to Christ’s Passion. When we look at the Virgin looking at her sleeping Child, we expect her to be happy, but she’s not. The sleeping Child is a prefiguration of the dead Christ. As the curators at the National Gallery write about Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna of the Meadow “the pose, position and pallor of the Child all echo images of the Pieta, the images of the dead Christ on His mother’s lap after the crucifixion.” (Figs 9, 10)

Figure 9. Madonna the Meadow, Giovanni Bellini, 1500

9a. Pieta, Michelangelo 1499

Figure 10. Sleeping Christ Child with instruments of the passion

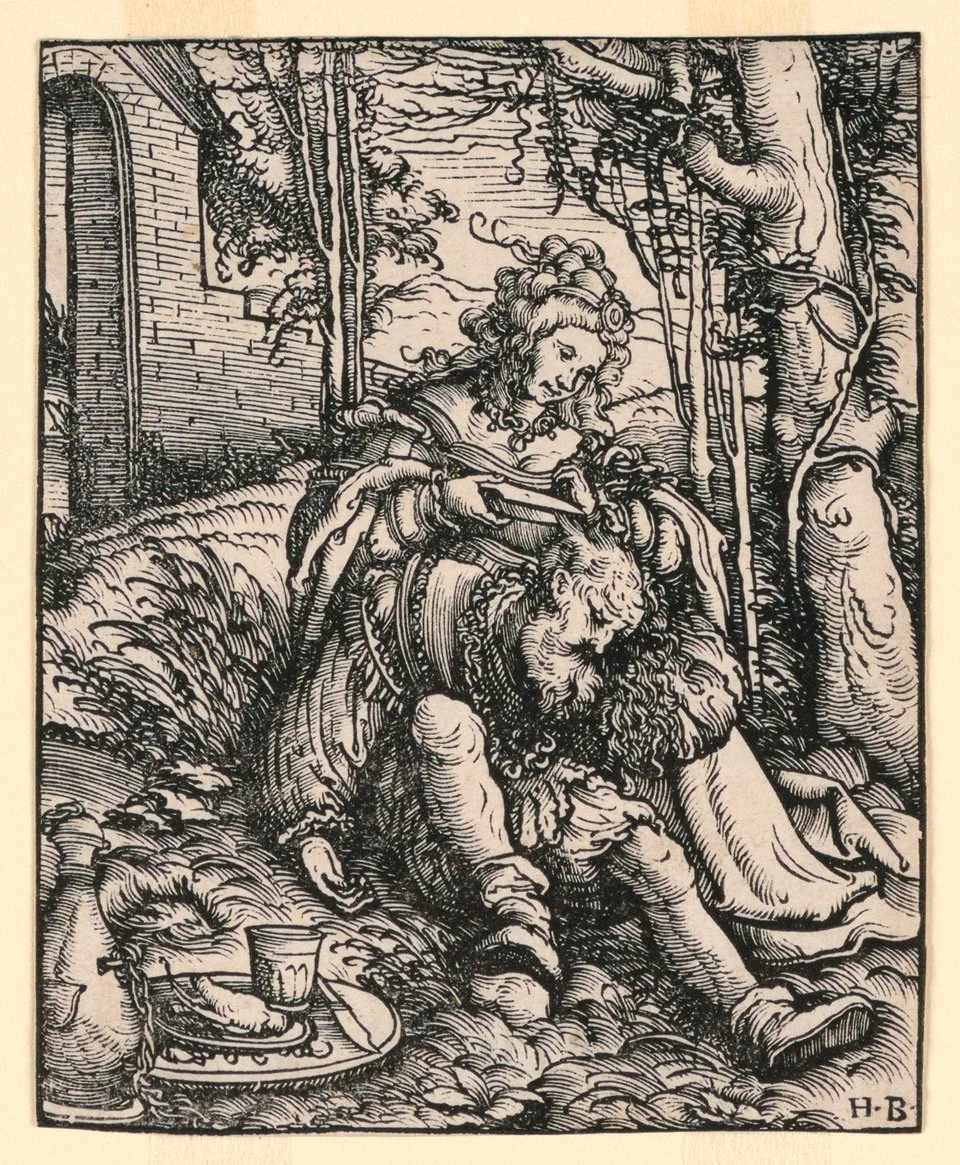

We’ve already seen a few images of men sleeping in the Old Testament and none of those images show the men to best advantage. But it gets worse, there’s Delilah cutting off Samson’s hair as he sleeps. He’ll be much the worse for it when he awakes. But Holofernes won’t be waking up at all, after the Old Testament heroine Judith hacks off his head. The sleeping Sisera into whose head Jael hammers a tent peg is also a goner. (Figs 11-13)

Figure 11. Delilah cutting off Samson’s hair

Figure 12. Judith Beheading Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi

Figure 13. Jael hammering a tent peg into the head of Sisera, Artemisia Gentileschi

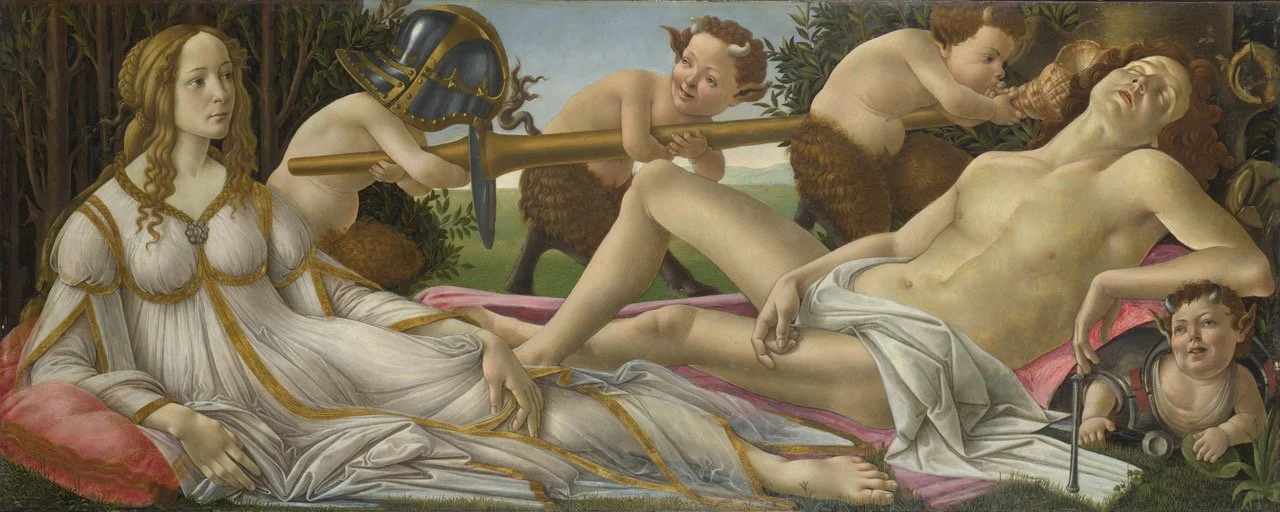

There’s one more image that we can place into the category of alert woman and sleeping man. It’s not from the Bible and it doesn’t show or imply brute force. Instead the subject is sexual conquest. Botticelli’s painting, Venus and Mars shows an alert and fully dressed Venus, amused at the condition of her companion, a nearly nude, sleeping Mars, who has been reduced to a state of ‘limp defenselessness.” Renaissance theory posited that sexual intercourse exhausted men and invigorated women. (Fig 14)

Figure 14. Venus and Mars, Sandro Botticelli, 1485

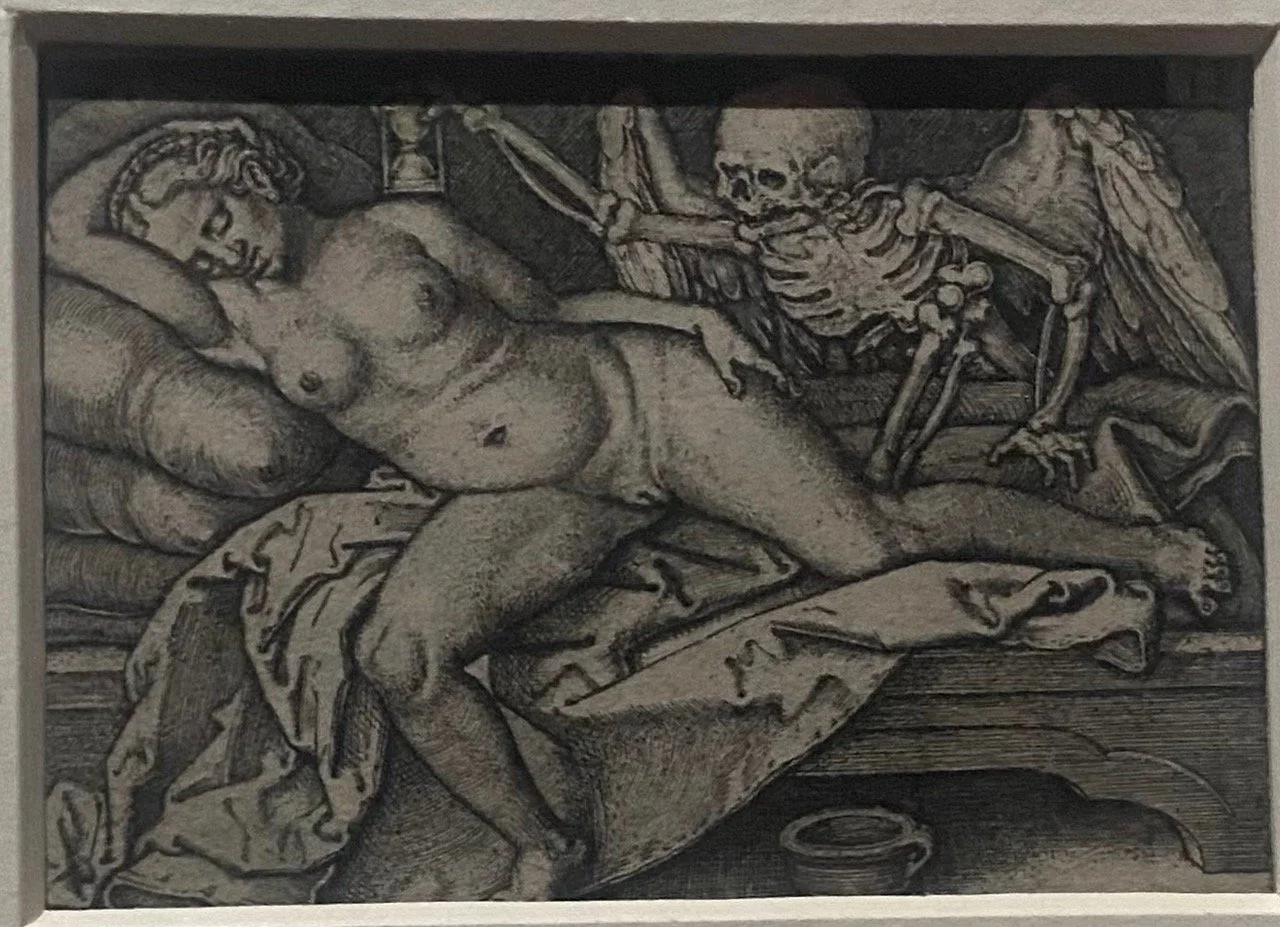

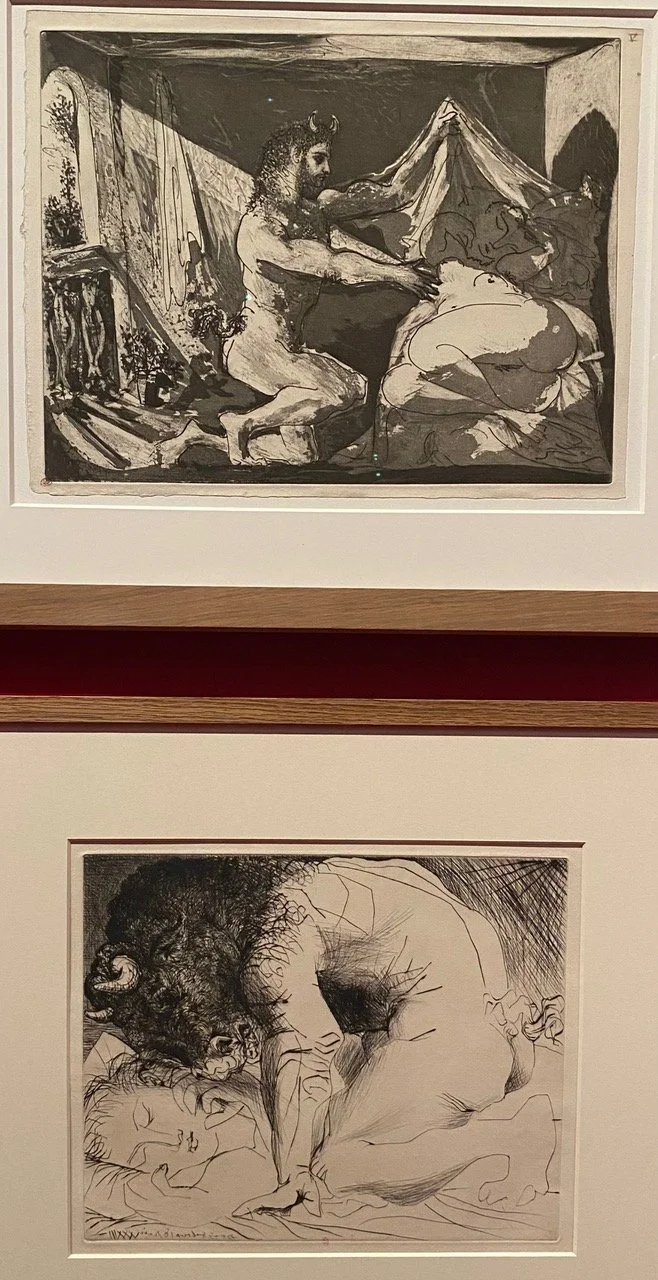

When the roles are reversed, that is, when the sleeper is a woman, the male is usually spying and the woman is more often than not, naked and vulnerable - to both the male gazing at her and to us, the viewer. I am sure that you are now asking yourself this question: when we see a prone female body in a painting, print or sculpture, how are we to know whether she is dead or asleep. In Greek and Roman sculpture and Renaissance and later paintings and prints that followed, the sleeping figure has one arm raised, bent at the elbow with hand mostly hidden behind her neck/head. (Figs 15 - 18)

Figure 15. Death and the Maiden, Hans Sebald Beham, 1548

Figure 16. Jupiter and Antiope, top Edouard Manet, 1856 after Titian (1551), bottom J.A.D. Ingres, 1851

Figure 17. Jupiter and Antiope, Picasso Top, after Rembrandt, 1936 bottom Minotaur caressing woman, 1933

Figure 18. Antiope with Jupiter as a satyr, Rembrandt, 1659

In Christian theology, the Resurrection confirms the connection between sleep and death. In Greek mythology, it is Night that brings Sleep and Death. The curator of the exhibition offers a scientific explanation, it was “probably inspired by atonia, the loss of muscular tonus during sleep and the external resemblance of death and sleep.”

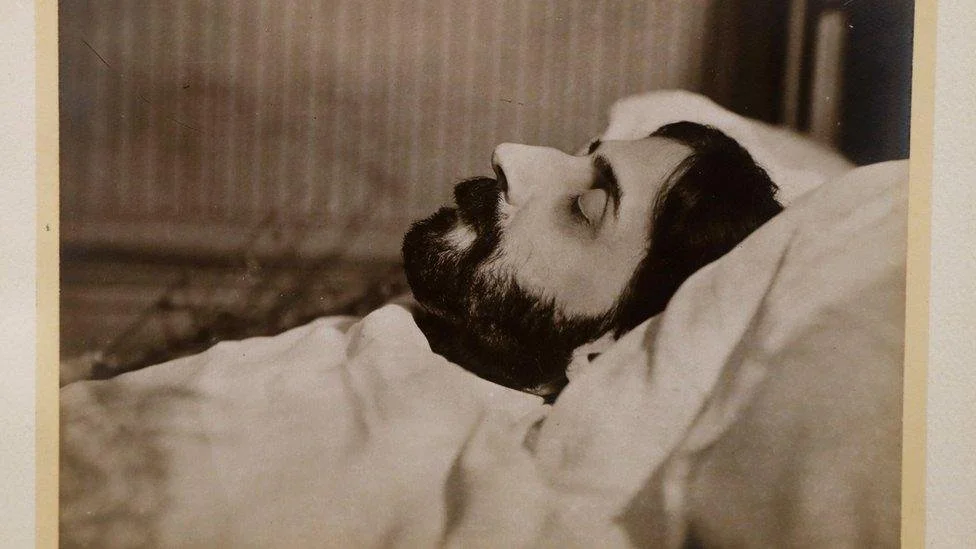

In the 19th century, paintings and photographs of people on their death beds were reminders of the “proximity of eternal rest to daily sleep.” Nadar photographed Victor Hugo on his deathbed and Man Ray photographed Marcel Proust in bed, two days after he died. (Figs 19, 20) Proust and sleep could have been an entire exhibition. As a child, the narrator of A la recherche du temps perdu, dreaded banishment to his bedroom, away from his beloved maman. Even as he waited for her final good night kiss, he agonized, knowing that the kiss would be followed by her departure and he would be plunged into loneliness and despair. Proust was an insomniac. Finally rather than trying to sleep, he lay awake all night, in his bed, in his cork lined room, writing.

Figure 19. Victor Hugo on his deathbed, Nadar, 1885

Figure 20. Proust on his deathbed, Man Ray, 1922

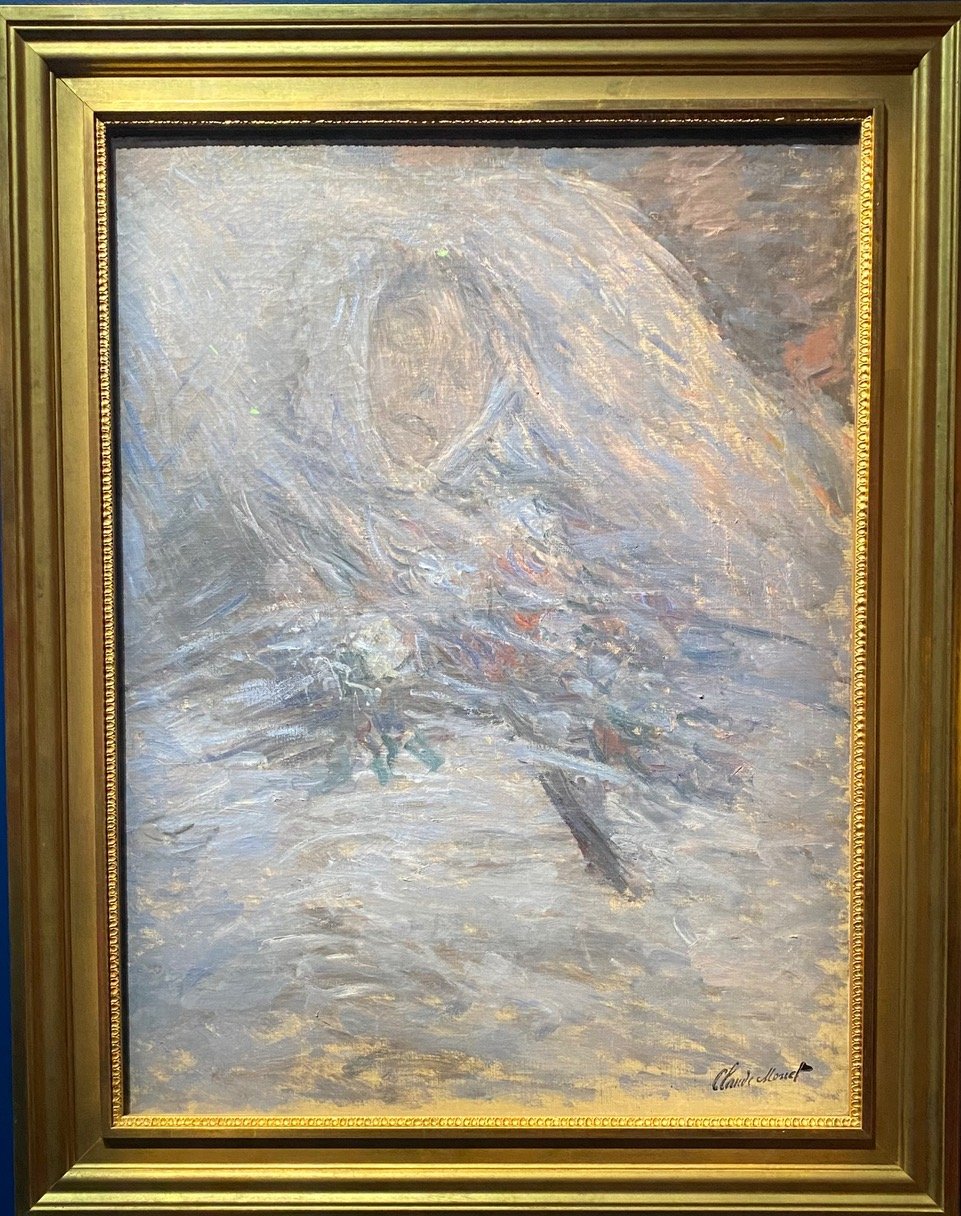

Claude Monet painted his wife Camille, dead. But it’s to the painter Ferdinand Hodler that the prize for obsessively documenting death must go. In 120 paintings and drawings, executed over two years (1913-1915) he chronicled the physical toll that cancer took on his mistress Valentine Godé-Darel. His images show him as a painter “torn between the desire to immortalize the memory of his beloved and a macabre impulse to capture death directly.” Godé-Darel died in January 1915. For the next 3 years, Hodler, suffering from chronic lung disease, got weaker and weaker. From his bed, it wasn’t self portraits that he painted but scenes of Mont Blanc, from his window. (Figs 21, 22)

Figure 21. Camille, dead, Claude Monet, 1879

Figure 22. Valentine Godé-Darel dying, Ferdinand Hodler, 1914

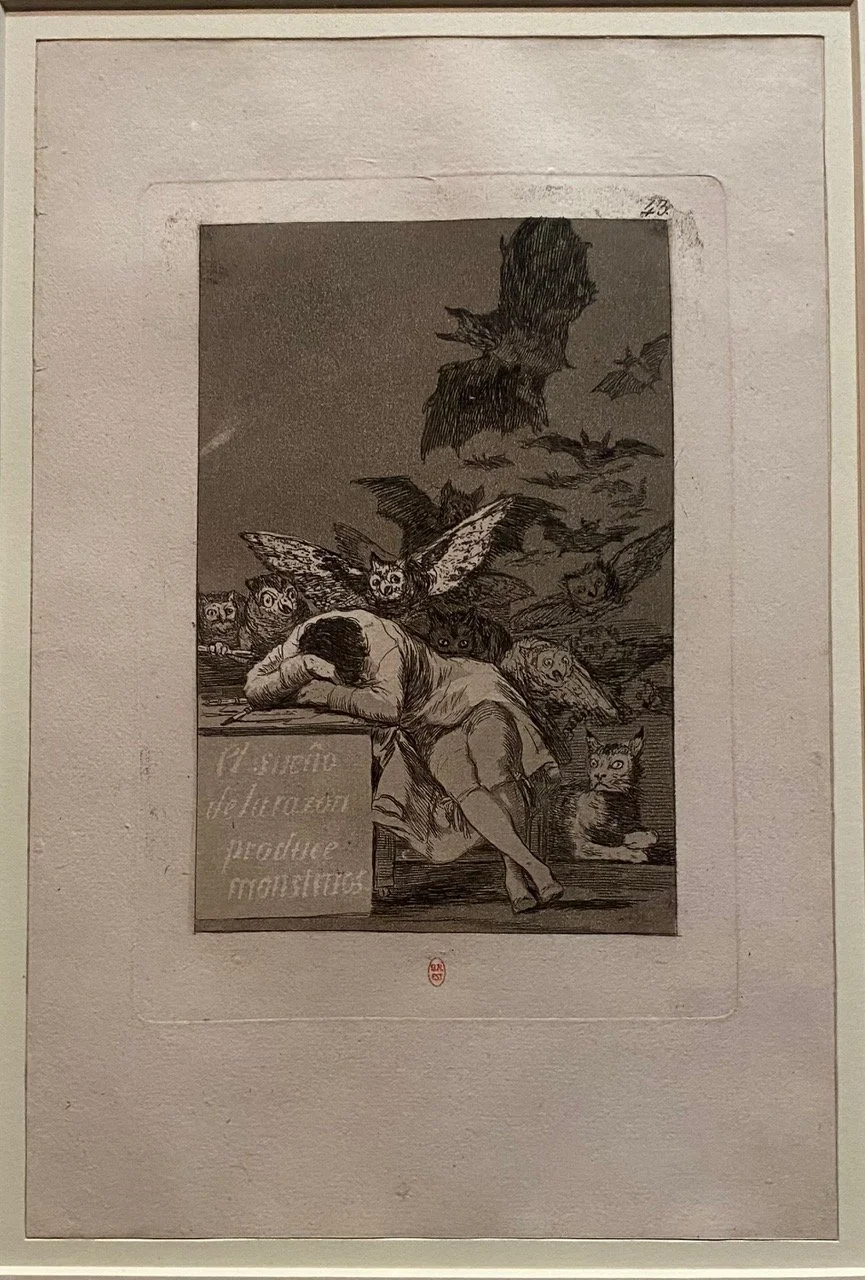

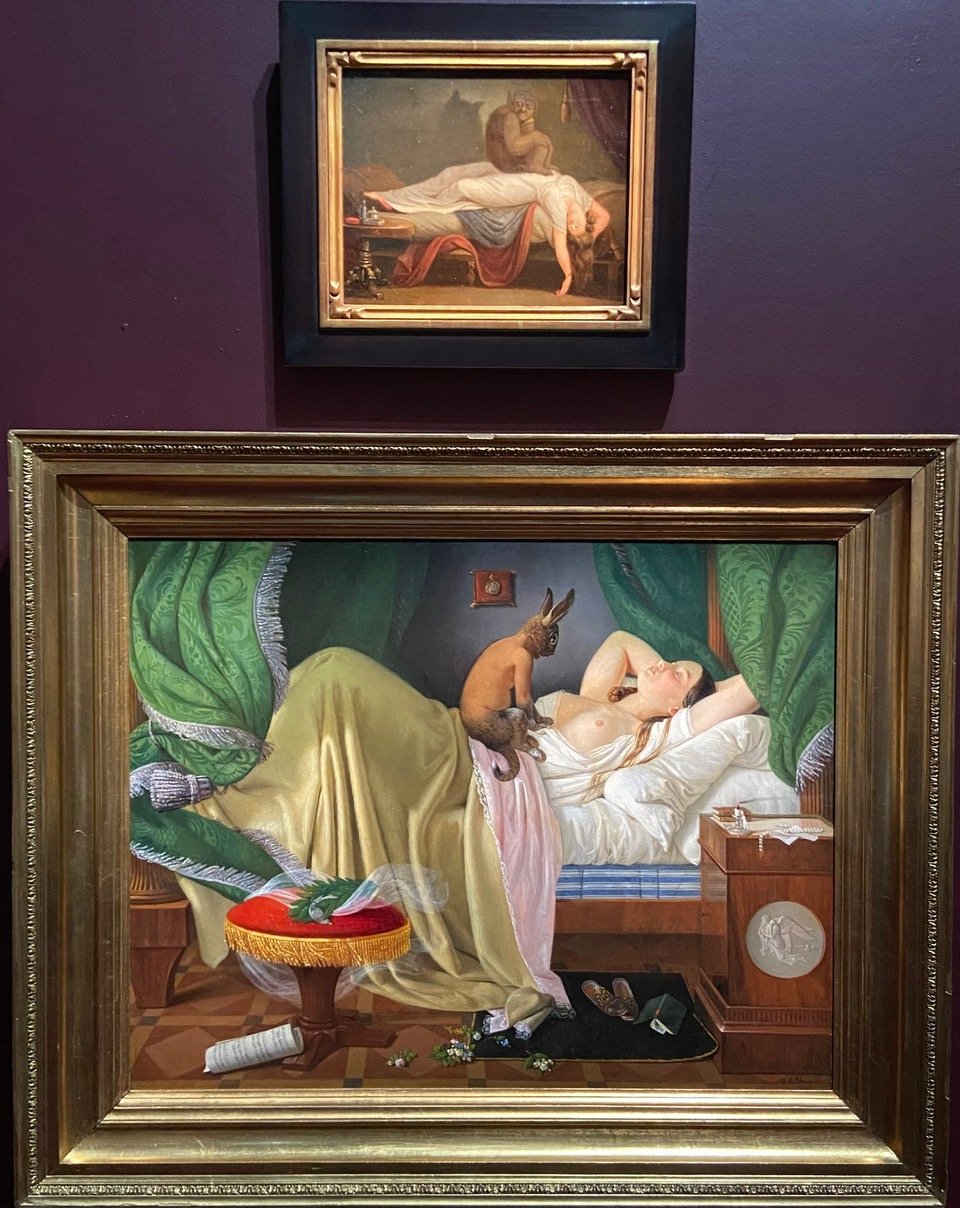

Sleeping is the gateway to dreams. From Homer’s time until Freud’s, people interpreted dreams by asking, “What do they portend, what do they mean for the future.” With Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), dreams metamorphosed. They were no longer prophetic but reflective. Dreams became the road “to the unconscious mind, functioning primarily as disguised fulfillments of repressed wishes, often sexual or aggressive, that are unacceptable to the conscious mind. Freud believed dreams offer a coded message about our deepest, often uncomfortable, truths.” Which make dreams not so different from nightmares. Which are fun to depict, if the number of paintings of disturbed sleep is any indication. (Figs 23, 24)

Figure 23. The Sleep of Reason produces monsters, Goya, 1799

Figure 24. Top, The Nightmare, Von Max (after Henry Fuseli), 1860; Bottom, The Nightmare, Ditty Blunck, 1846

Finding sleep, staying asleep is every tired person’s goal. But insomnia seems to plague more and more of us these days. How could it be otherwise, with artificial light, computer screens and cell phones beckoning, even when we know we should turn them off and try to get to sleep. “Blocked on all sides, sleep has become an object of desire, which we attempt to obtain by every means possible.” Back in the old days, there was opium and laudanum and hashish. Now sleeping pills are a massive global industry. Cures for sleeplessness are not going to be found anytime soon, not when treating insomnia is so profitable.

The final section in the exhibition is called ‘To Bed’ which made me smile because when parents in France want their children to go to their bedrooms NOW, they will say in a very loud voice, in a very insistent way - AU LIT!!! And that’s the name of this final section. The wall text tells us that the word 'chamber' (bedroom) comes from the Greek (kamara), and the "civilization of the bed" is Roman. And that the bed has always been an important item of furniture. For the poor, who mostly slept together and for the rich whose beds were in the living room. For we modern day folk, the bed, almost always in a separate room, is a ‘refuge and haven,’ with pillows and covers, it’s warm and cosy.

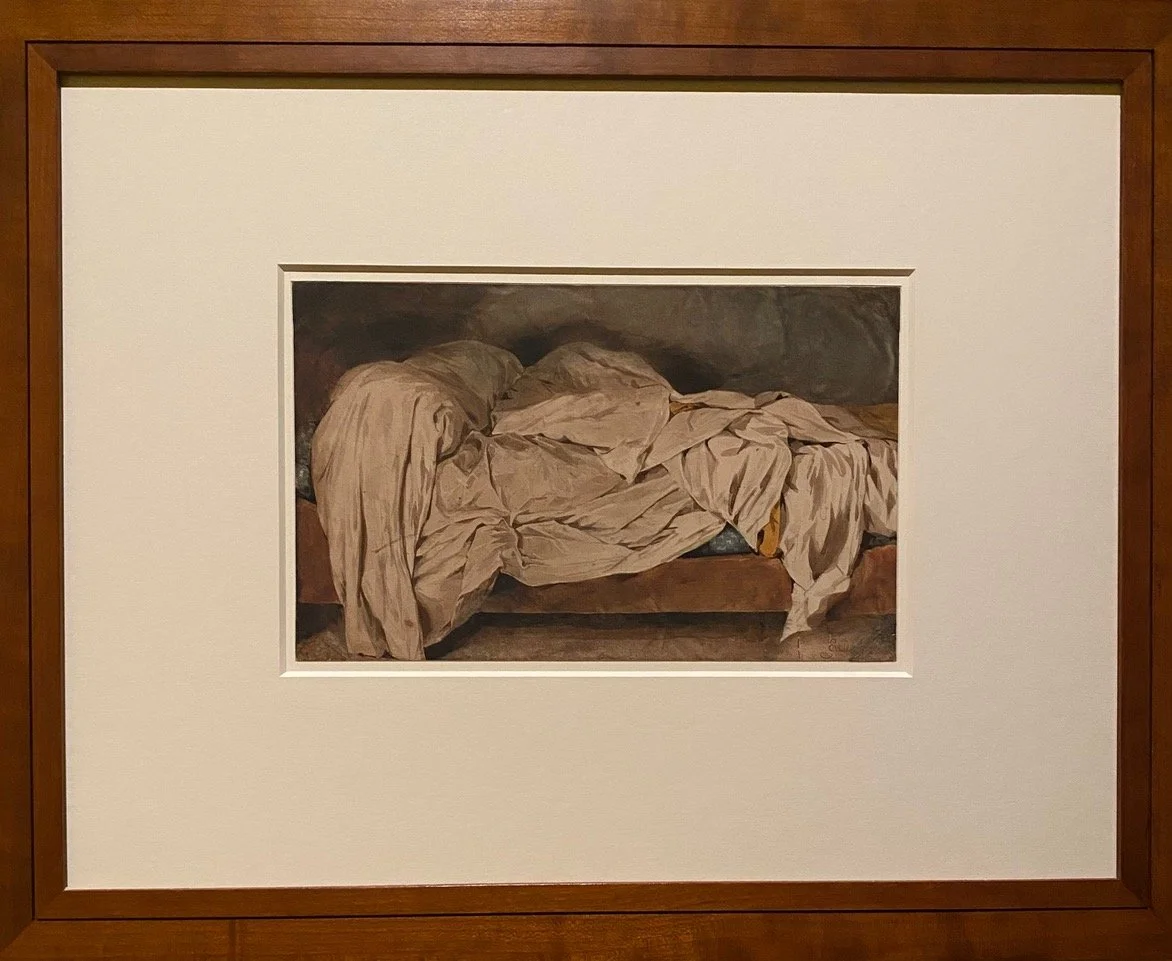

In times past, the bed was “the place of birth, of love, of illness and of death.” It currently retains (if the occupants are lucky) only one of these functions, beyond sleeping. The others have been relegated to the hospital bed. When the bed is a place of passion, the wall text tells us, it is simultaneously strange and familiar, a place of intimacy and a place of abandon. The images in this section include an unmade bed by Delacroix (1824) which the curators liked so much they chose it for the exhibition catalogue cover. To Bossi, the drapery evokes “something troubling, a restlessness.” (Fig 25)

Figure 25. Unmade Bed, Eugene Delacrois, 1824

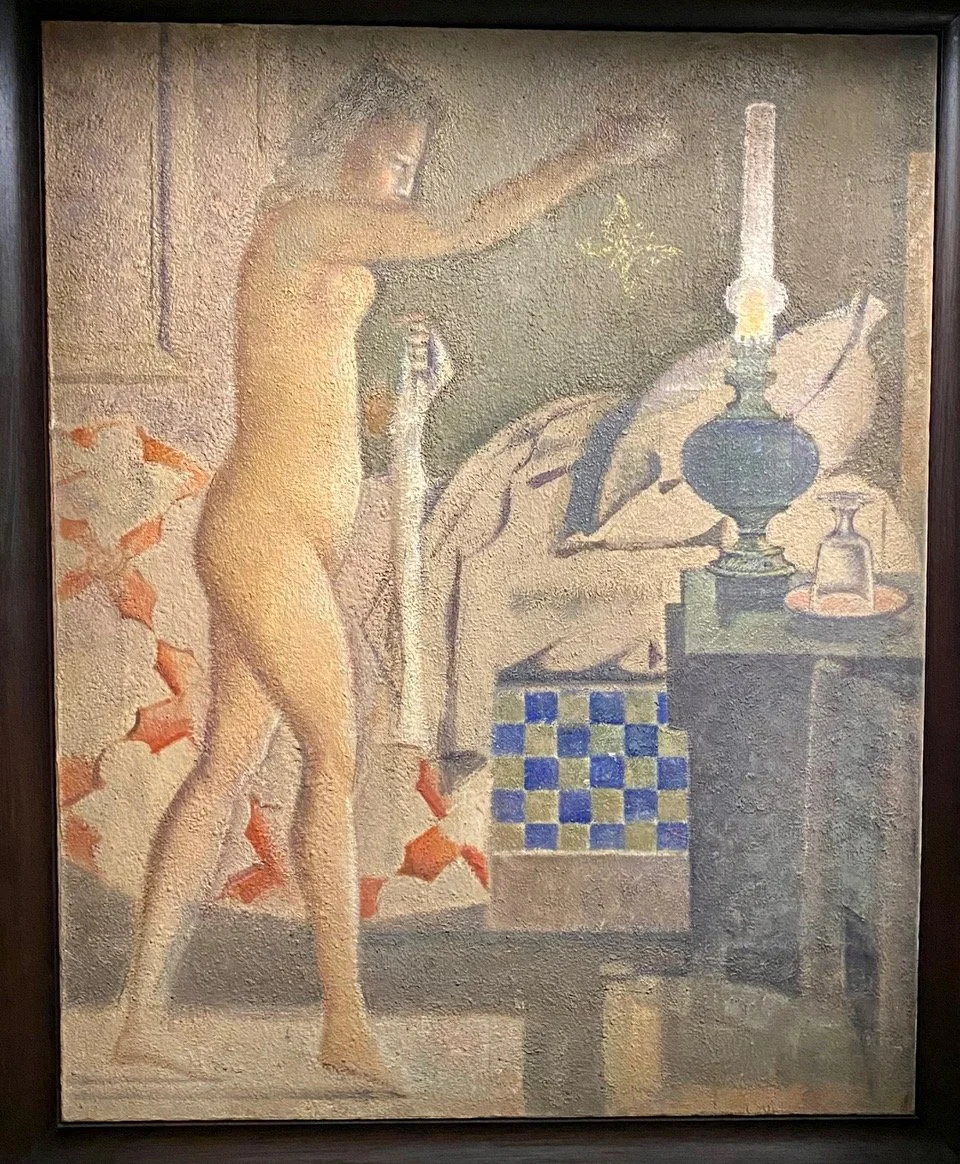

There is also a Balthus here, called La Phalène, The painting shows a young woman, nude, next to her bed, about to turn off her oil lamp. There’s an oversized moth next to the lamp, drawn to the light. Balthus’ use of casein tempera gives the scene a sense that we are seeing it through a veil. “Is this a real scene or just a dream, or the recollection of a dream?” The curators think that Balthus was evoking The Butterfly Dream by the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi. Briefly, "One day, Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering around, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable Zhuang Zhou. But he didn't know if he was Zhuang Zhou who had dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuang Zhou.” This painting is the last image in the exhibition but it was the first work that Bossi borrowed for it! (Fig 26)

Figure 26. La Phalène (Moth), Balthus, 1959

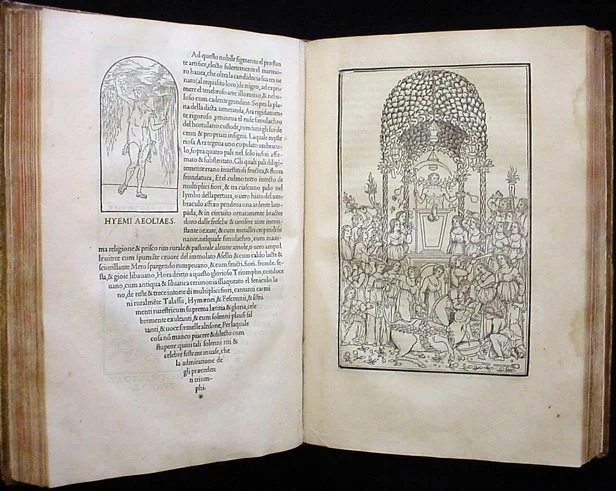

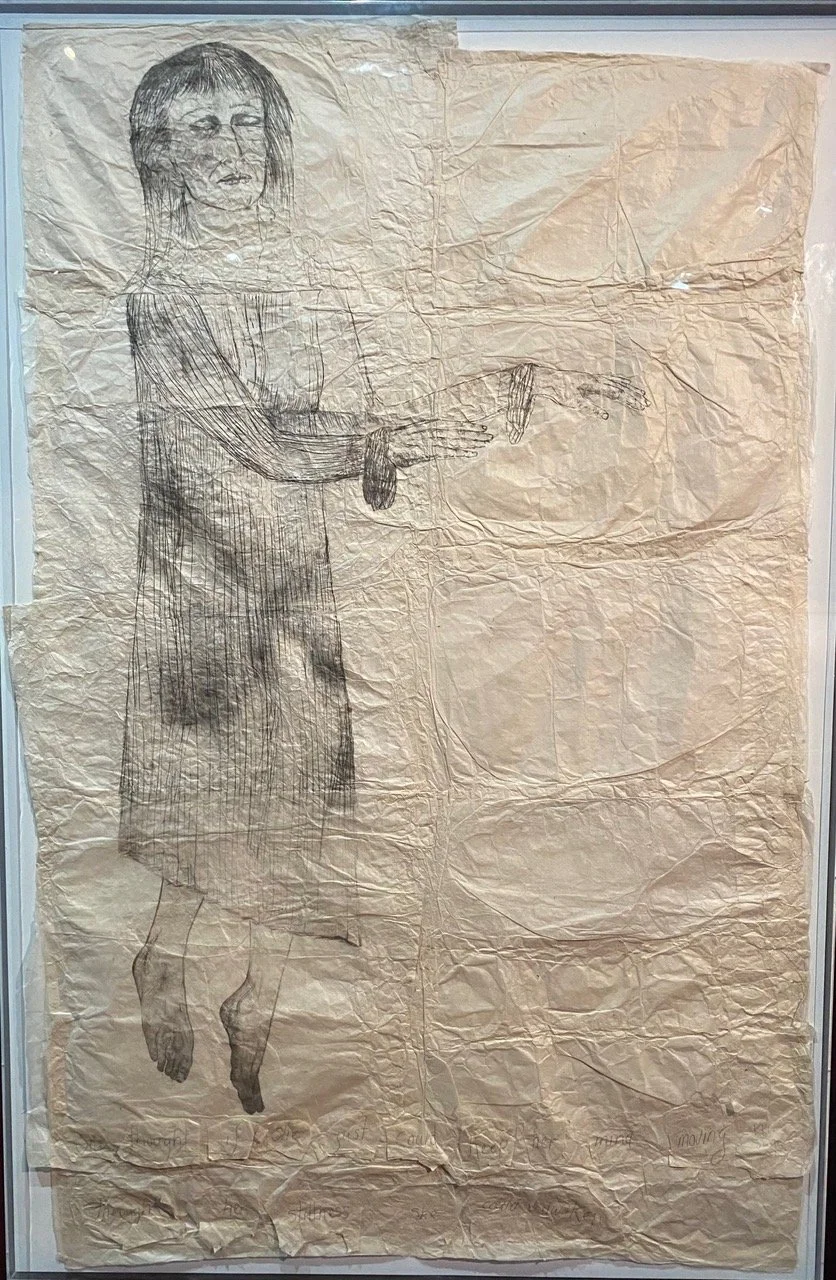

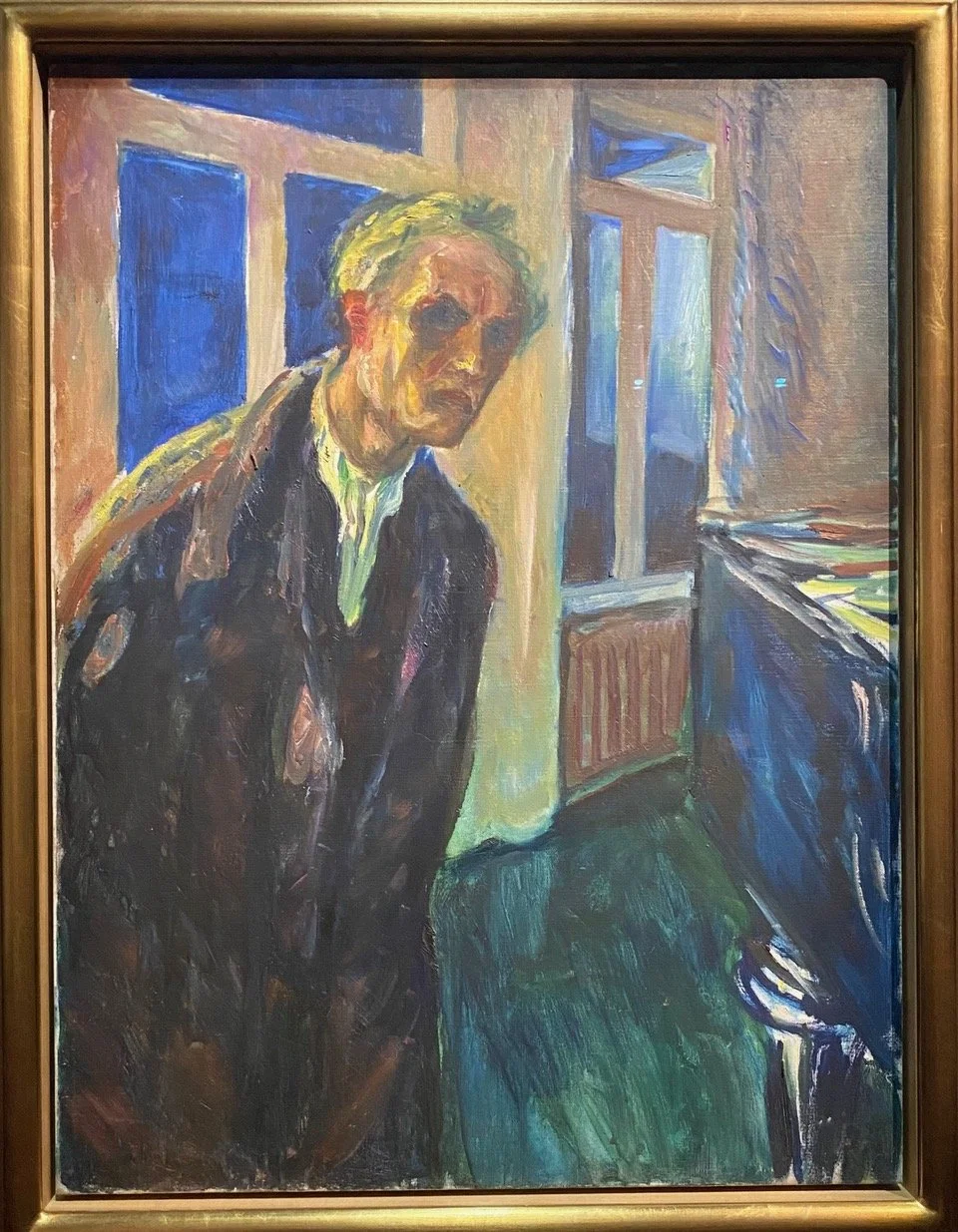

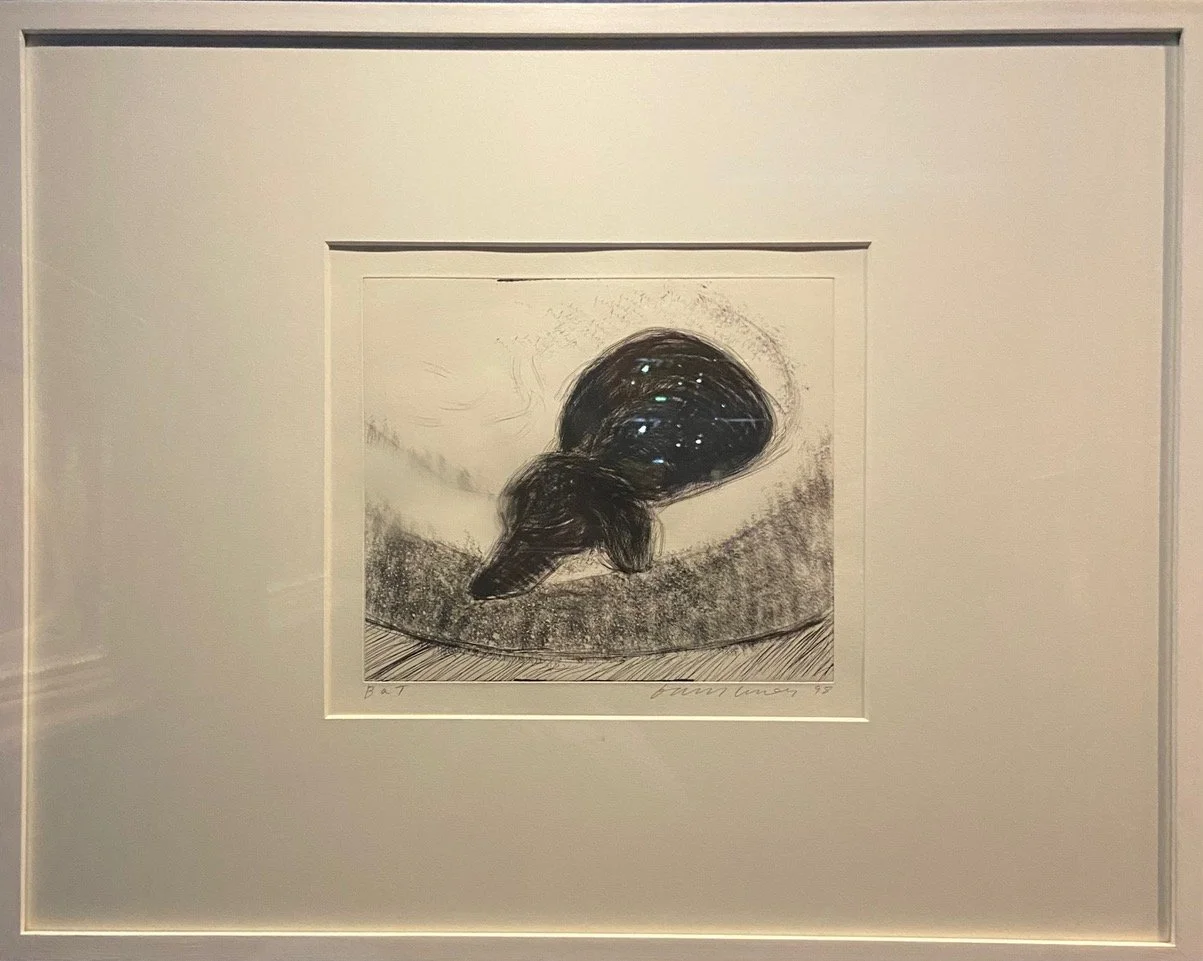

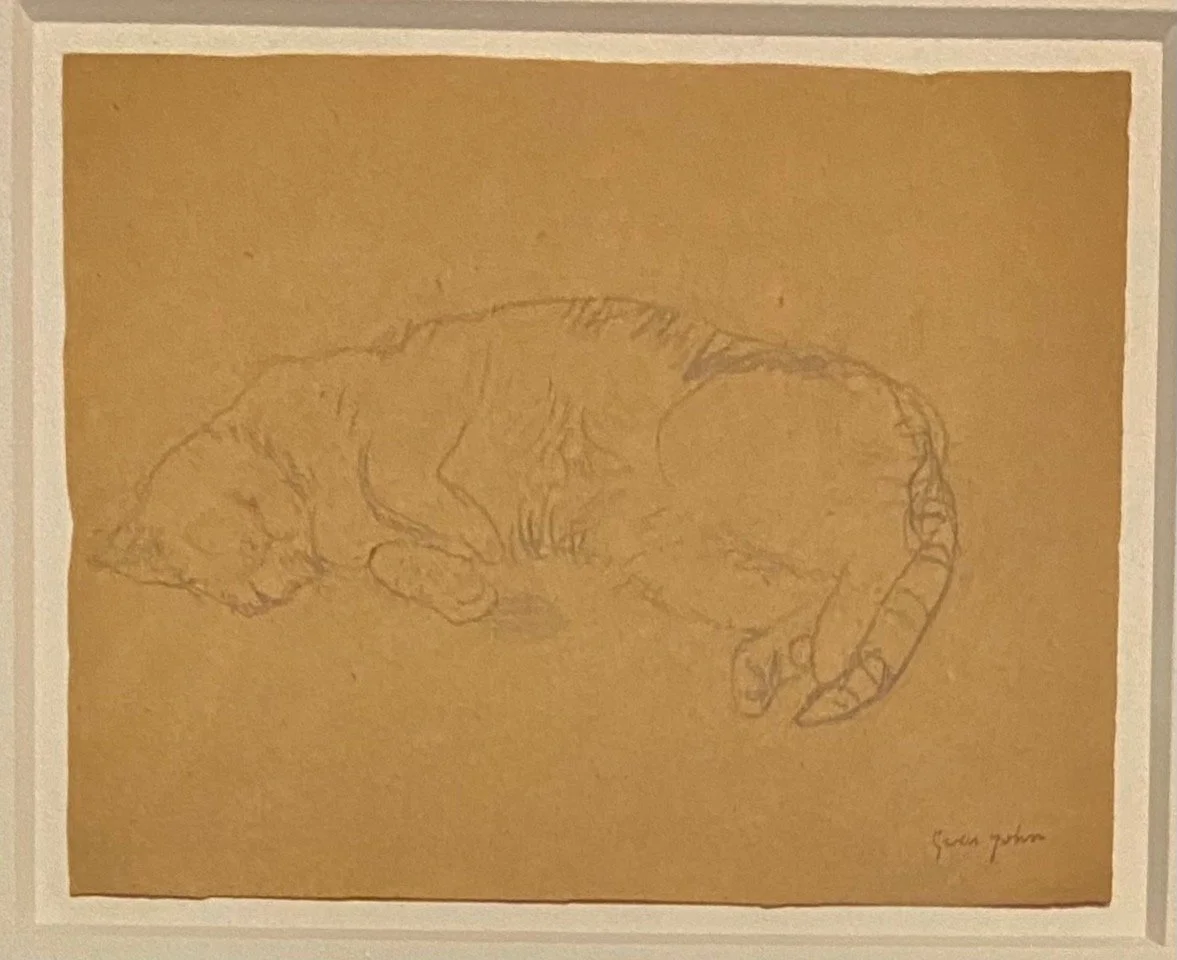

The exhibition is an eclectic mix of works by artists that you have never heard of and works by artists that you would never imagine seeing in an exhibition about sleep. A book from the Italian Renaissance which meant a lot to me a long time ago was here. The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, (1499) is a treatise by Francesco Colonna on gardens and dreams. A painting by Edouard Vuillard, shows his sister in bed, their mother by her side. His sister suffered a miscarriage and has come home to her mother to be soothed. There’s a painting by an artist I didn’t know, Charles Matton. It’s a cluttered art collector’s bedroom with hardly enough room for his bed. There’s a portrait of Monet’s infant son sleeping and another of a very sexy guy by Carolus-Duran, also sleeping. There’s a drawing of a sleep walker by a favorite artist of mine, Kiki Smith. And another sleepwalker by another artist whose name I didn’t know, Maximillian Pirner. There’s a self portrait by Edvard Munch as an insomniac, which he was. And finally, to lighten the mood, a drawing by another of my favorite artists, David Hockney. It’s one of his pooches, sleeping. (Figs 27-35) The exhibition is on through February, so go see it! Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 27. Hypnerotomachia Polipholi, Francesco Colonna, 1499

Figure 28. The Lullaby, Edouard Vuillard, 1893

Figure 29. The Art Collector’s Bedroom, Charles Matton

Figure 30. Jean Monet Sleeping, Claude Monet, 1868

Figure 31. Man Sleeping, Carolus-Duran, 1861

Figure 32. Sleepwalker, Kiki Smith 2001

Figure 33. Sleepwalker, Maximilian Pirner, 1878

Figure 34. Self portrait as an Insomniac, Edvard Munch, 1923

Figure 35. Sleeping dog, David Hockney, 1998

Figure 35a. Sleeping cat, Gwen John

Thanks for your Comments on The Worlds of Colette, about whom I have also become obsessed, expect to be hearing more about her in an upcoming post.

New comment on The Worlds of Colette:

Whether it’s painting or literature, you’re basically a genius at everything. Honestly, it’s getting a bit exhausting for the rest of us mortals to keep up with you! Your articles are a serious hazard to my ego! I dive in feeling like an expert, and by the end, I’m questioning if I even know the difference between a paintbrush and a toothbrush. It’s borderline illegal to have that kind of talent! Gerard, Versailles

Brilliant synthesis of Colette's many lives and how she transformed each into literature. The autofiction angle is particularly sharp, how both she and Proust treated their real lives as raw material for their novels but filtered through fiction's lens. I've been trying to track down a copy of Le Pur et L'impur after reading this (that critique of Proust's Gomorrah feels kinda necessary) since lived experience trumps imagination when writing desire.