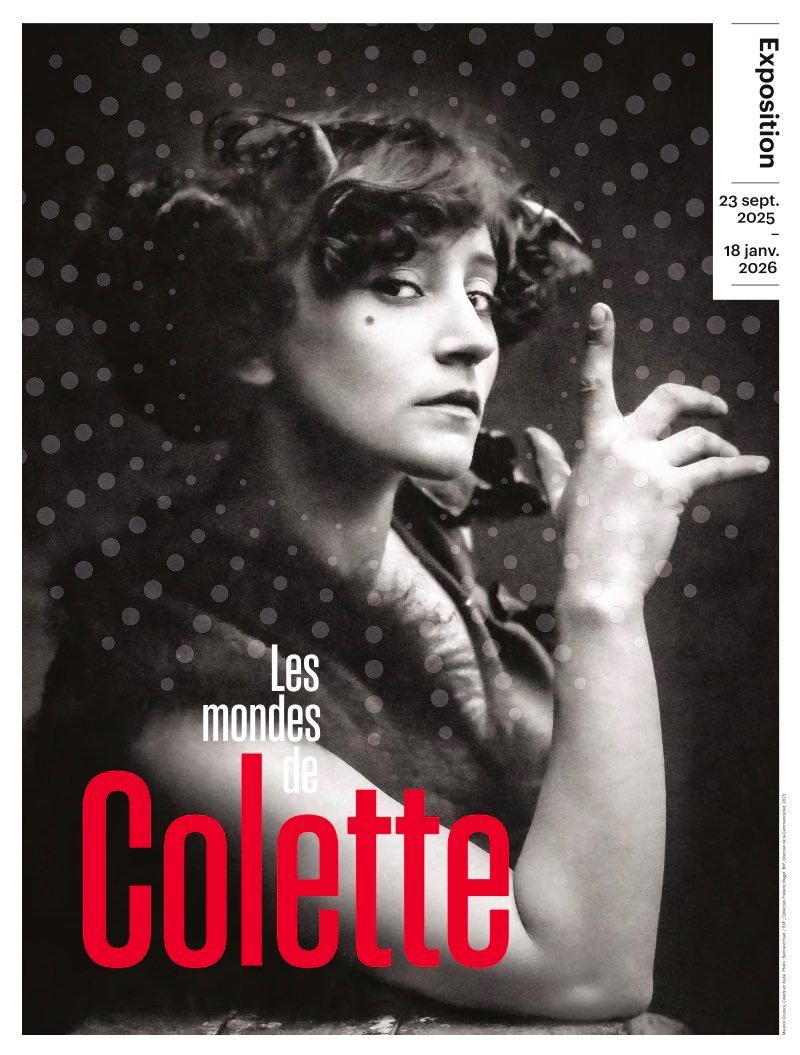

The Worlds of Colette

Bibliotheque National de France

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. In the week before I left Paris, I gorged on exhibitions, anticipating the famine that awaited me. One exhibition was at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), a mammoth structure that reads well in plan and in aerial views but which, when experienced ‘in real time’ is mostly a nightmare. A maze that gives you (me) very little sense of accomplishment once you (I) finally find the right path. Designed by Dominique Perrault, the library hails itself as “a bold statement of minimalism and urban integration.” Minimalism, that’s for sure, urban integration, hmmm. This building is everything Frank Gehry’s buildings are not. The Gehry designed Fondation Louis Vuitton has a playfulness and human scale that Perrault’s design sorely lacks. The world is a better place for having Frank Gehry buildings in it. RIP Frank Gehry. (Figs 1-3)

Figure 1. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Dominique Perrault (supposed to look like 4 open books)

Figure 2. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Dominique Perrault, Interior

Figure 3. Fondation Louis Vuitton, Frank Gehry

Fig. 3a. Ginevra and Nicolas with Frank Gehry’s Fred and Ginger building in Prague

Colette (1873-1954) should have triggered an exhibition or two a couple years ago. I guess the library had to choose between Colette and Proust (1871-1922). Or maybe everyone was just exhausted after the Proust exhibition since putting together an intellectually satisfying and visually engaging exhibition about a writer is never an easy task. For this exhibition, portraits of the American heiress Nathalie Clifford Barney and the American dancer/jazz singer Josephine Baker are here, as are paintings by Colette’s contemporaries, Jacqueline Marvel and Raoul Dufy. How do these people figure in Colette’s life and work? Here’s one clue, Barney was a lesbian and Colette and Baker were, too, at least some of the time! Marval painted the women Colette wrote about and Dufy illustrated one of Colette’s books. (Figs 4-6)

Figure 4. Nathalie Barney Clifford

Figure 5. Les Coquettes, Jacqueline Marval, 1903

Figure 6. Pour un herbier, Colette text, Raoul Dufy, watercolors, 1948

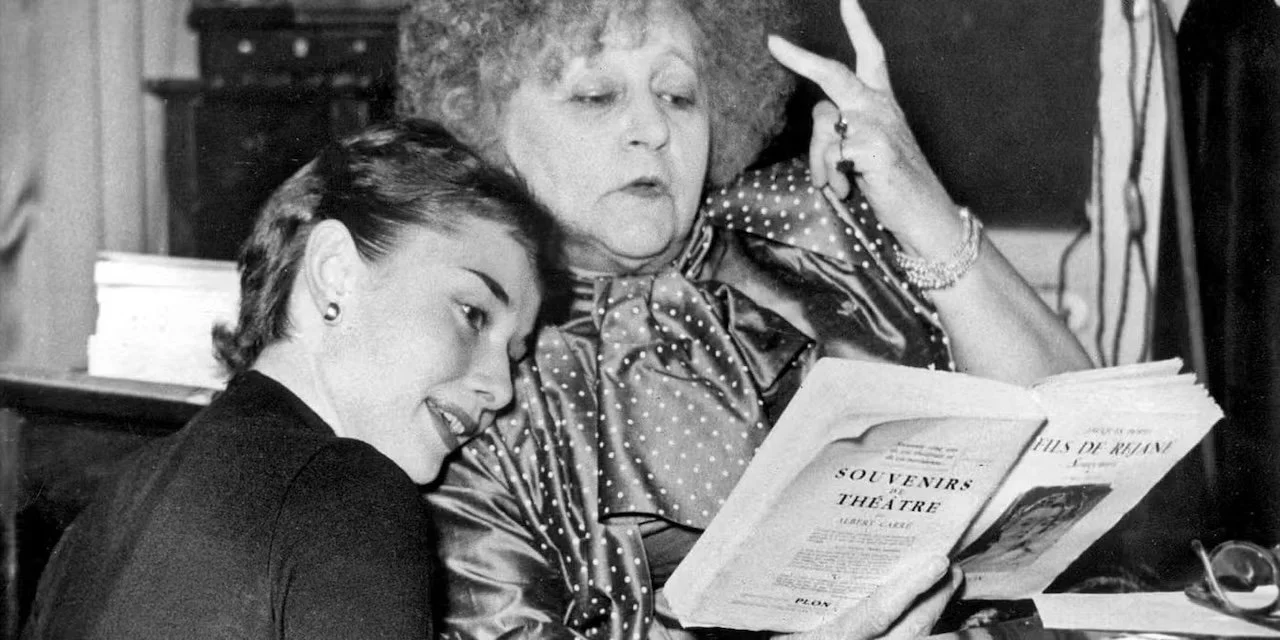

Everyone has heard of Colette or has seen an adaptation of her book, Gigi (1944). On Broadway, where Audrey Hepburn (discovered by Colette) played the title role or on film, where Leslie Caron did. Gigi is the story of a 16 year old girl who is learning her profession at the knees of her great aunt and grandmother, celebrated Parisian courtesans of the Belle Epoque. Their goal for Gigi is to find a wealthy lover and become his mistress. Gigi follows her own path instead, falls in love and gets married. (Fig 7)

Figure 7. Colette and Audrey Hepburn, 1951

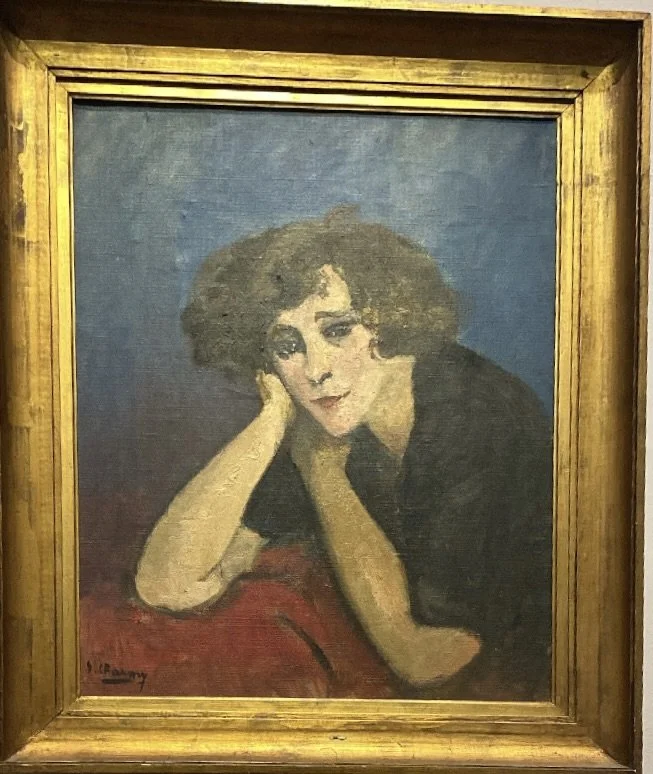

Colette was, as the curators tell us, “a 20th-century literary icon,” awarded the Légion d'Honneur and celebrated by a state funeral; read by the masses and respected by her peers. “In her texts, readers found an unembellished take on the human condition as it applied to a wide range of women. In her life, they saw an independent spirit navigating a century marked by violence against women in many forms.” (Figs 8-10) The curators contend that Colette is a woman for our own time, who considered “questions about identity, self-representation, desire, how we relate to the body, and to others.”

Figure 8. Portrait of Colette by Jacques Emile Blanche, 1905

Figure 9. Portrait of Colette by Emilie Charmy, 1921

Figure 10. Portrait of Colette, Emilie Charmy, 1921

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette was born in 1873, in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye - associated with her, as Nohant is with George Sand and Illiers-Combray is with Proust. Colette was the daughter of Captain Jules-Joseph Colette and Adèle Eugénie Sidonie, the daughter of a wealthy mulatto merchant from Martinique. So like the writer, Alexandre Dumas (The Count of Monte Cristo), Colette had both black and white ancestry.

Until she was 12, Colette and her family lived in a comfortable bourgeois home with a beautiful garden (since 2016 a museum). Colette’s mother had an inheritance from her first husband and Colette’s father, a war hero and disabled veteran, had a lucrative sinecure. Alas, through serious mismanagement, Colette’s father lost most of the family’s money. Forced to sell their home and its contents, the family moved to a nearby town in to a more modest home. As the exhibition shows again and again, the garden of her childhood home was never far from her thoughts. It was Colette’s paradise lost. Her love of flora and fauna and memories of her mother’s botanical knowledge wove their way through her works and her artistic collaborations for the rest of her life.

And maybe too, the kind of person she became was a result of having and then losing something as precious as her family’s home and garden. That sort of experience can leave you scarred and inclined either to take risks or avoid them. Being her father’s daughter, she took them. And was to live, with as many ups as downs.

In 1891 when Colette was 19, a man whose own father had been in the army with Colette’s, a Parisian named Henry Gauthier-Villars, paid a visit to the family. He was attracted by Colette’s beauty. She was attracted by the possibility of escaping the provinces and moving to Paris. They married in 1893. (Figs 11, 12)

Figure 11. Portrait of Colette and Willy, Eugène Pascau, 1903

Figure 12. Colette and Willy, Roger-Viollet, 1902

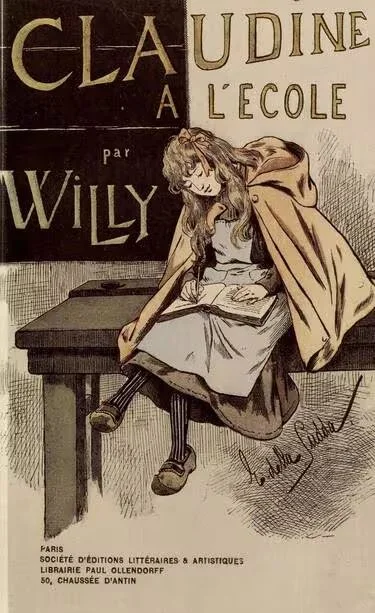

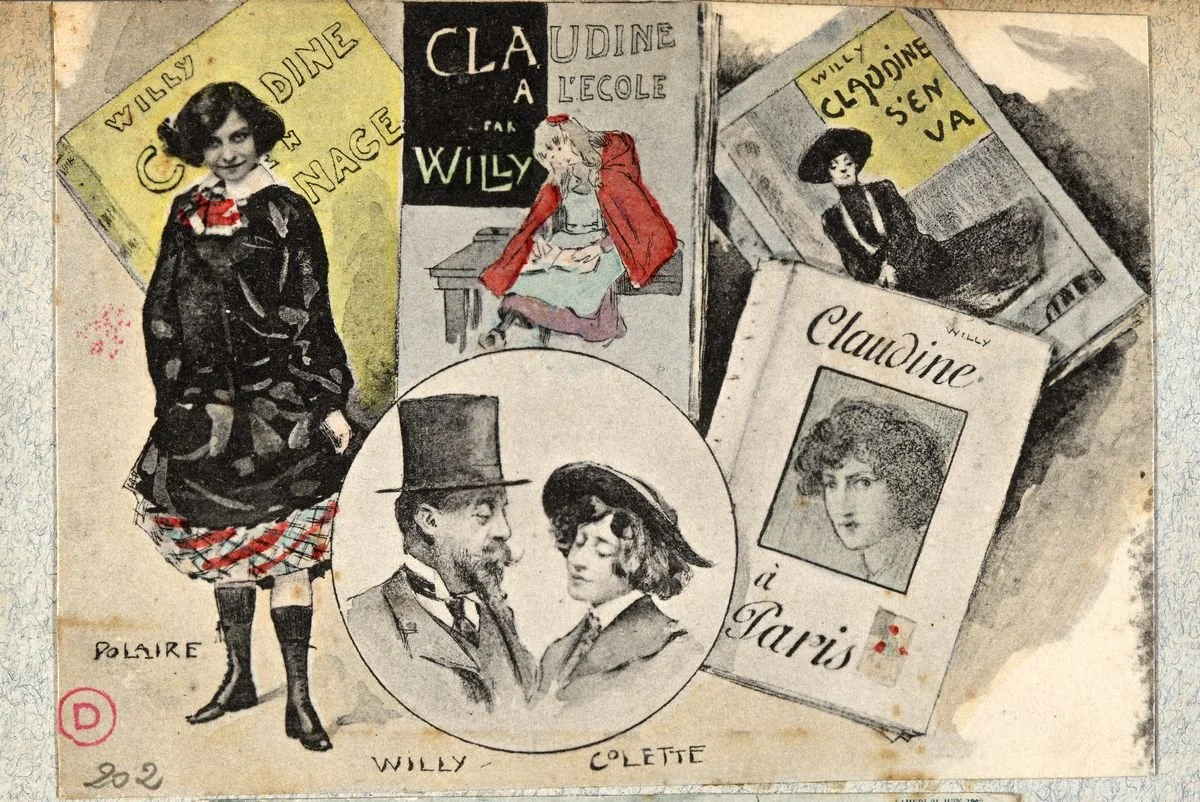

Colette’s husband, 14 years her senior, was an author who mostly signed work written by others and publisher and promoter whose pen name was Willy. Colette decided to become a writer, too. This is how Willy helped her achieve her goal. He locked her in a room until she wrote the requisite number of pages for that day. Alas, all of Willy’s maneuvers were not so benign. He also had her first four novels published under his name. Not theirs. His. Those novels are her four Claudine books which appeared, one a year, from 1900 to 1903. The narrative begins in a public (not Catholic) girls school, modeled on the one Colette attended from ages 6-17. The story is only semi-autobiographical. Willy had Colette spice her story up by infusing her memories with a Sapphic sensibility. Titillating, sensational stories always sell better. (Figs 13-15)

Figure 13. Claudine at School by Willy

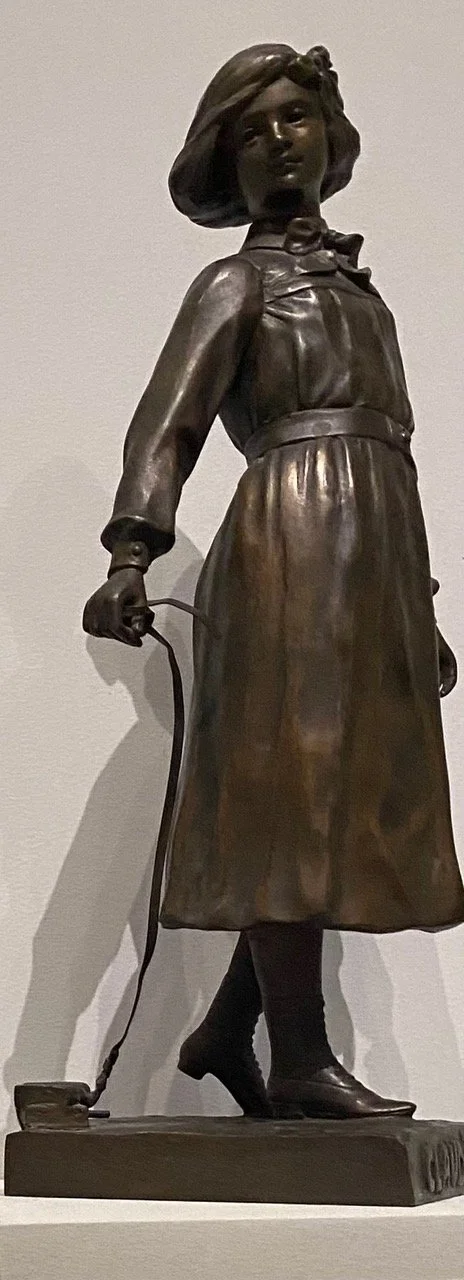

Figure 14. The four novels of Claudine with portraits of Willy & Colette

Figure 15. Claudine as school girl figurine, among the many items produced that capitalized on the novels’ popularity.

As it turns out, one thing that Claudine and Colette did have in common was that they were both married to libertines. Willy, in addition to introducing Colette to artists and intellectuals, encouraged her nascent lesbianism. During the decade they were together, Colette went from being jealous of Willy’s sexual dalliances to accepting them and finally to participating in them, at least with other women. In the fourth and final book in the series, Claudine leaves her libertine husband for another woman and so did Colette.

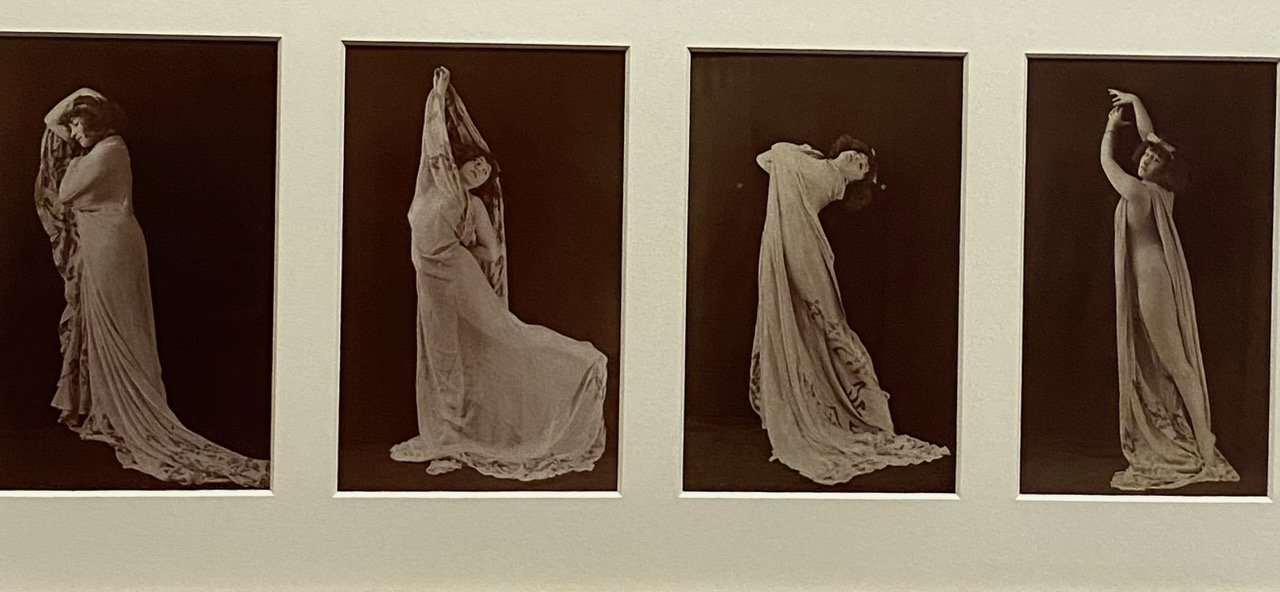

By the time she and Willy separated in 1906, Colette was in a relationship with the niece of Napoleon III, the Marquise de Belboeuf, called both Missy and Max (when she dressed like a man). When Colette left Willy, she also left her source of income, the royalties from the sales of her Claudine books. For the next 6 years, Colette earned a living by performing as a mime, dancer and gymnast, first in Paris and then in the provinces. She sometimes played Claudine and mostly earned barely enough to survive. The Marquise occasionally appeared on stage with Colette. Once, at the Moulin Rouge, they apparently misjudged the sophistication of their audience and shared an onstage kiss in a pantomime about Egypt. Colette was a scantily clad mummy and Max a male archeologist. Their kiss caused a near-riot, the police were called, the performance was shut down and Max’s parents stopped sending her money.(Figs 16-19)

Figure 16. Colette and Missy (Max) Marquise de Belboeuf on stage

Figure 17. Colette dancing

Figure 18. Colette’s poses

Figure 19. Colette and her training equipment

Colette recounted this period of her life in La Vagabonde (1910), in which she considers the price a woman, here called Renée, pays to maintain her independence in a male society. James Hopkin, on the 100th anniversary of the book’s publication waxed rhapsodic about Colette, calling her the “mistress of metaphor … with more punch than Proust..” With “descriptions that are often laugh out loud funny, at once cruel and compassionate, but usually followed swiftly by a warm, reflective melancholy….” When Renée's yearns “(for the countryside idyll of her childhood, for love, or to be free of love), she is always sure to pinch herself awake with wit…” (Guardian 2011)

Colette wrote another kind of book about her experiences as a performer, L'Envers du music-hall (The Underbelly of the Music Hall). The book is a series of scenes and portraits, which, like *La Vagabonde*, offers “an often poignant panorama of the lives of music hall artists,” describing both how they train their bodies and how precarious their lives were. Colette had begun taking photos and her photos of performers backstage “provide a rare visual record” of these people “who also populate the paintings of Kees van Dongen, a neighbor of hers and Marie Laurencin, a close friend.” (Figs 20, 21)

Figure 20, Nina at the Folies Bergère, Kees van Dongen, 1909

Figure 21. La Danseuse Couchée, Marie Laurencin

In 1912, Colette married Henri de Jouvenel, a diplomat and the editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper, Le Matin. Colette’s career as a journalist began, even as her career as an author continued. In her book Cheri, Colette considers the attraction between an older woman, in this case a wealthy courtesan, and a younger man. Colette had been publishing the book serially when, in 1920, she began an affair with her husband’s 16 year old son, Bertrand. Colette was 47 (her own daughter, with Bertrand’s father, was 7). Maybe Colette started the affair as a research project but when Colette’s husband learned of it in 1924, he found a suitable heiress for his son and ended his marriage to Colette. More fodder for the mill, Colette’s next novel, Le Blé en herbe was also about a sexual encounter between an older woman and a much younger man.

Colette may have lost her step-son, but her attraction to younger men didn’t disappear. A year after she and Henri Jouvenal divorced, Colette married her third husband, Maurice Goudeket, 16 years her junior. (Fig 22). More about him later.

Figure 22. L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, libretto Colette, music Ravel, 1919-1925, Little Boy in his Nursery

Colette lived almost all of her adult life in Paris, although for many years she also owned properties in the countryside. The first was a villa in Brittany, near Saint-Malo that the Marquise de Morny bought for them. Apparently, when Colette and the Marquise went to sign the deed of purchase, the notaire refused to let the Marquise sign. Why? She was dressed as a man. When Colette sold that property, she bought a villa on the Cote d’Azur, near Saint-Tropez. As the exhibition curators note, “These houses, nestled in their natural surroundings, are like echoes of her childhood home in Saint-Sauveur, while offering different views, flora, fauna, and friendships.”

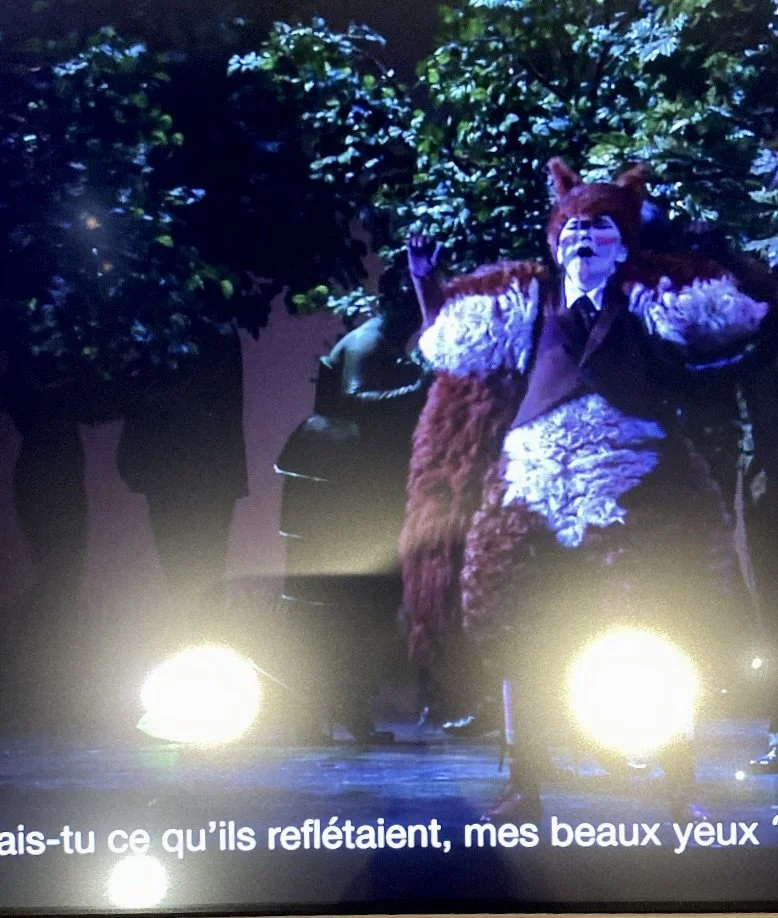

In 1915, Colette was commissioned to write a libretto for what ultimately became an opera with music by Maurice Ravel. Delayed by World War I, it eventually premiered in Monte Carlo, in 1925, choreographed by 21 year old George Balanchine. Written in eight days, “L'Enfant et les Sortilèges (The Child and the Spells)…explores “anger and cruelty ….tempered by humor and poetry …” Colette explained it this way, "If a child could tell about this childhood while he is passing through it,…his account would perhaps be nothing more than one of intimate dramas and disappointments.” In three acts, a little boy goes from being naughty to the toys in his bedroom to being naughty to the animals in his garden to finding grace when he bandages the paw of a wounded squirrel. The opera concludes with animals and toys joining the little boy as he calls out for his Maman. According to Margaret Reynolds (Guardian, 2012),“The ‘Maman’ that ends Colette's libretto is a cry of loss and pain: Colette's, when she wrote the text, Ravel's, when he came to compose the music. It was the cry of all those wounded soldiers that Colette saw at her hospital (during WWI), that Ravel saw at the front.…” The opera was performed in 2012 in Glyndebourne, in 2020 in L,A. and in 2025 in Monte Carlo.(F. 23-25)

Figure 23. L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, libretto Colette, music Ravel, 1919-1925, Little Boy in the Garden

Figure 24 L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, libretto Colette, music Ravel, 1919-1925, Monte Carlo, 2025

25. L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, libretto Colette, music Ravel, 1919-1925, Glynbourne Production, 2012

In 1928, after both her second marriage and affair with her step-son came to a tumultuous close, Colette wrote ‘La Naissance du jour,’ set in her villa in Saint Tropez. The book is “a lyrical and introspective work about a woman in her fifties reflecting on love, independence, and nature (in which) the narrator/author confesses that most of the prominent characters in her novels are avatars of herself.”

Claudine is the first avatar. In four novels, she goes from school girl to woman fleeing her husband. Renée, in La Vagabonde (1910) prefers independence on the road to being stuck in a conventional marriage. Léa in Chéri and The Last of Chéri, (1920, 1926), is a “sophisticated courtesan in her late 40s (who) is both lover and mentor to a much younger man. With Léa, Colette explores the taboo subject of older women. Claudine, Renée, Léa, Colette’s three ages of woman. According to Colette Fountain (Smithsonian Magazine, 2023), in Chéri and Gigi, Colette “explores the everyday issues that women face, from their relationships with men to their fears about aging and isolation….. Her subject is the full range of female desires, from men to sex to financial independence to general autonomy,… “ Her women, her avatars are “fully fleshed-out female characters.”

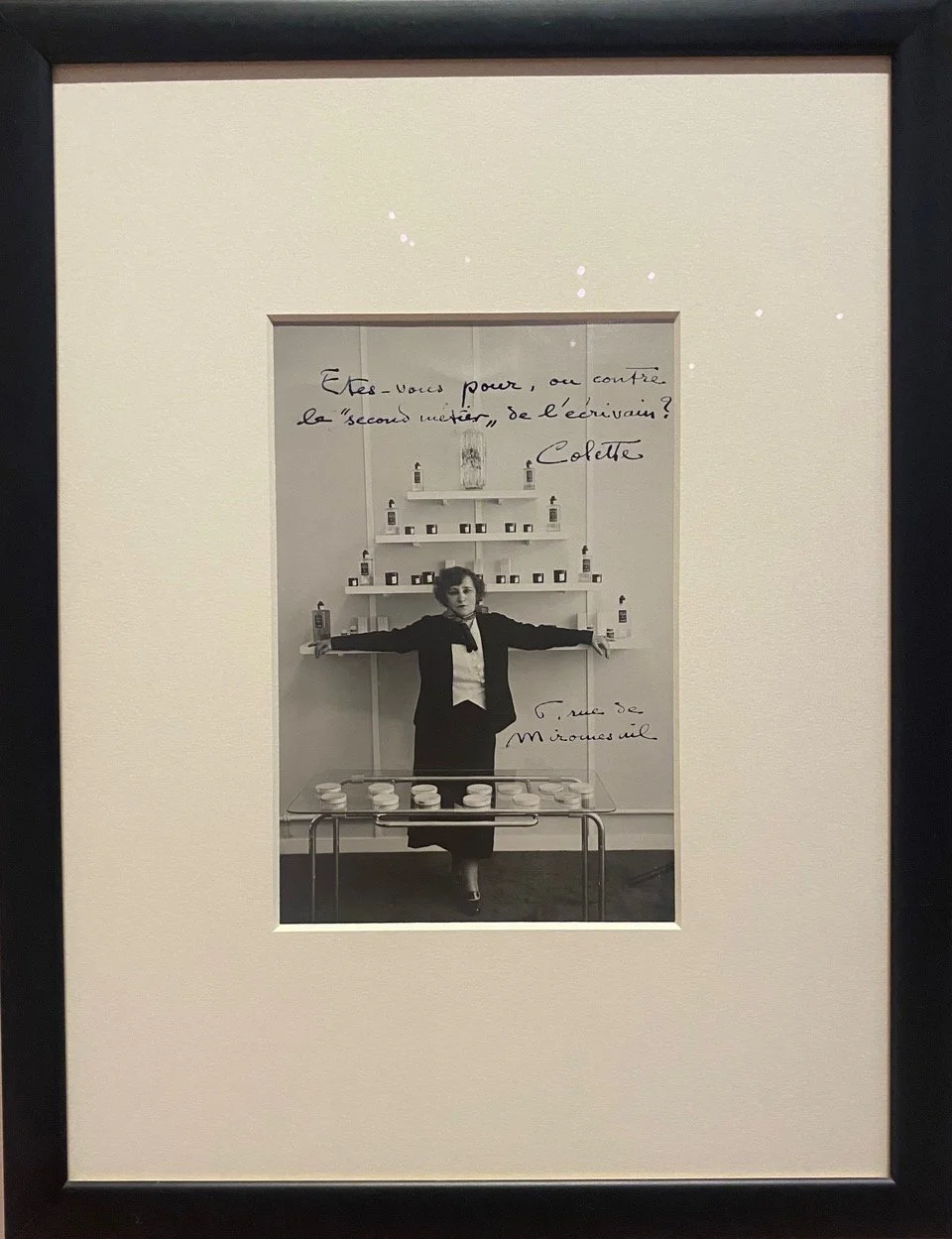

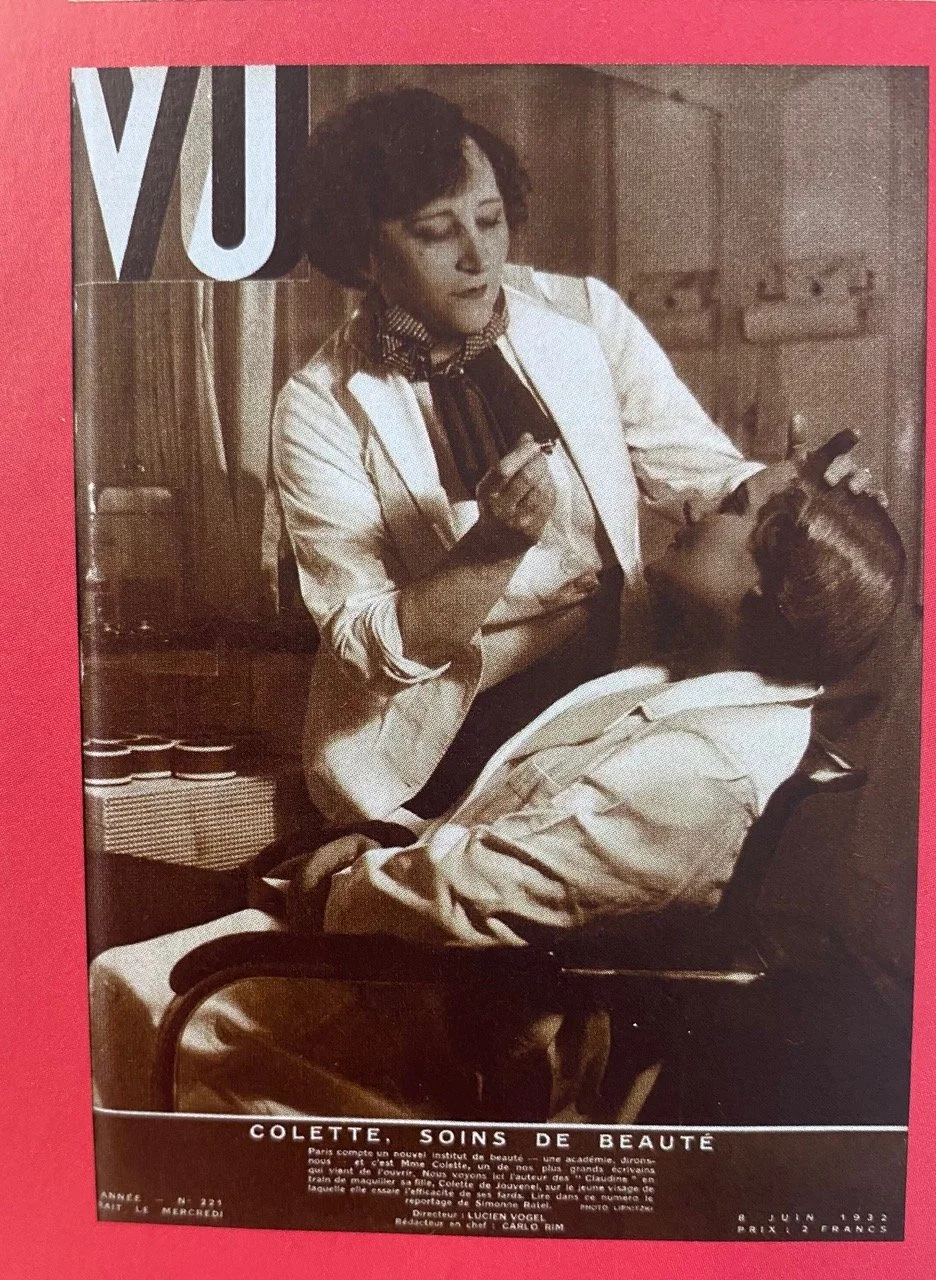

Following the financial crisis of 1929, Colette opened a beauty salon. “Are you for or against a writer having a second profession?” Is how she advertised her salon. “When you are a woman and you wish to be independent, you have to earn a living” is how she responded to criticism. Colette created her own perfumes and cosmetics. Colette’s beauty salon was a failure. According to Nathalie Barney, when women walked out of the salon, they looked 15 years older. The only kind of make-up Colette knew how to apply was the face paint actors wore on stage. (Figs 26-28)

Figure 26. Colette at her Beauty Salon

Figure 27. Colette in her Beauty Parlor applying makeup to a client

Figure 28. Colette’s Beauty Parlor products

Colette was 67 years old when Nazis occupied France. She remained in her apartment in the Palais-Royal with her Jewish husband. He was arrested by the Gestapo in December 1941 and although he was released 7 weeks later, a second arrest with worse consequences hung over them. Oddly (or maybe not - she was an anti-Dreyfusard), even as she hid her Jewish husband and worried about his safety, she wrote lifestyle articles for pro-Nazi newspapers and a novel Julie de Carneilhan, full of anti-Semitic slurs.

After the war, crippled by arthritis, cared for by her young husband and surrounded by her cats, she sat in her chair and then in her bed, by the window, looking at the beautiful Palais Royal garden beyond. (Figs 29, 30) And she continued to write.

Figure 29. Colette on the balcony of her apartment at the Palais Royal

Figure 30, Colette and Maurice Goudeket in her Palais Royal apartment, Lee Miller (photographer)

BONUS - THE PROUST CONNECTION (Figs 31-33)

Figure 31. Antoine Compagnon's (at Academie française induction) lecture on Proust & Colette

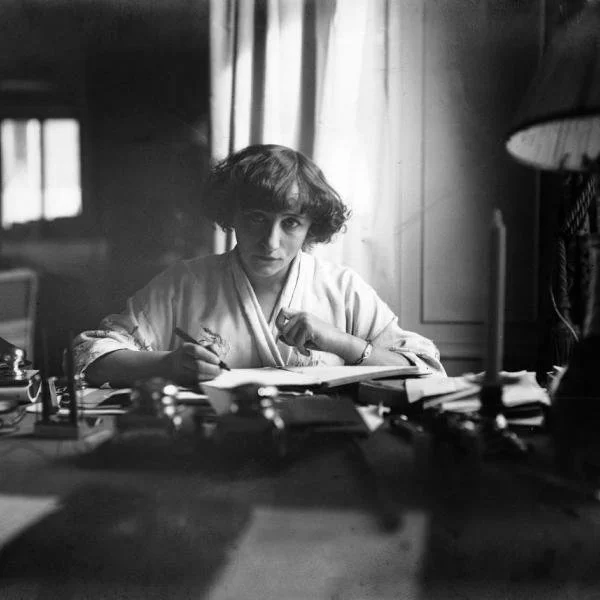

32. Colette Writing

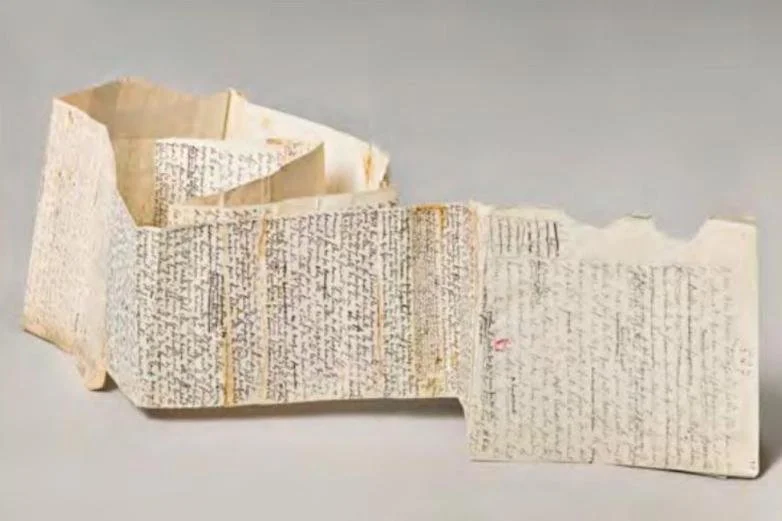

Figure 33. Proust’s paperoles, editing before word processors.

Proust’s name was not mentioned in this exhibition. But I knew there had to be a Proust connection. Proust and Colette were contemporaries after all. And then, before I could start poking around, looking for clues, I received a lovely email from Shiao-Ping, a new reader who lives in Brisbane, Australia. She had just read one of my pieces on Proust. She told me about a Proust Society in Connecticut. On their website I found a lecture by Antoine Compagnon, the Proust scholar who curated two of the Proust exhibitions in Paris a few years ago. His topic - Colette and Proust!

Here’s a bit of what I learned. When Colette moved to Paris with her first husband, Willy, she met Proust at the fashionable literary salon of Mme Arman de Caillavat. Who became Proust’s model for Mme Verdurin in Swann in Love. Proust and Colette were not simpatico. The reasons were many and varied. Among them - they were on opposite sides of the Dreyfus Affair; he was a wealthy Parisian, she was a country girl; Proust avoided scandals, Colette came to thrive on them; Proust’s ambition was always to be a writer, Colette was willing to earn money anyway she could - from writing books and newspaper articles to performing on stage and opening a beauty salon.

Compagnon referred to a short biography of Proust by Edmund White (1999). According to White, “The great Colette completely failed to sense his value when she first ran into Proust in 1894….” She recounted that first meeting this way, “I met Marcel Proust at Madame Arman de Caillavet's, and I didn't much care for his excessive politeness, the exaggerated attention he paid to those he spoke with, especially the women, an attention that too clearly emphasized the age difference between them and him. He seemed remarkably young, younger than all the men, younger than all the women. Large, dark, melancholic eyes, a rosy, sometimes pale complexion, an anxious gaze, his mouth, when silent, tight and closed as if for a kiss... Formal clothes and a disheveled lock of hair.”

Twenty years later, Colette’s opinion of Proust changed when she was given a copy of Swann’s Way. Proust’s description of Combray became her model for describing the village of her childhood. The way he wrote about his mother influenced how she would write about hers.

White described Proust’s appearance a few years before he died like this, “He was very ill, he weighed no more than one hundred pounds, and he seldom emerged from his cork-lined room. He had become a martyr to art…” Here is what Colette wrote about Proust near the end of her own life, “For many years, I stopped seeing him. He was already said to be very ill. And then, one day, Louis de Robert gave me "Swann's Way"... What a revelation! The labyrinth of childhood and adolescence reopened, explained, clear and breathtaking... Everything one would have wanted to write, everything one hadn't dared or known how to write, the reflection of the universe on the long, flowing stream, troubled by its own abundance….We exchanged letters, but I hardly saw him more than twice during the last ten years of his life. The last time, everything about him announced, with a kind of haste and exhilaration, his approaching end.

Around the middle of the night, in the lobby of the Ritz, deserted at that hour, he was receiving four or five friends. An open otter-fur coat revealed his frock coat and white shirt, his cambric cravat half-untied. He kept talking with effort, trying to appear cheerful. He wore on his head—because of the cold, and apologizing for it—his top hat, tilted back, and a lock of hair fanned out across his eyebrows. It was, in short, an everyday formal uniform, but disheveled as if by a furious wind that, having blown his hat onto the back of his neck, rumpled his shirt and the fluttering ends of his cravat, and filled the furrows of his cheeks, the hollows of his eye sockets, and his gasping mouth with black ash, had pursued this tottering young man, fifty years old, all the way to his death. (Vol. 3, Complete works of Colette, Robert Laffont Edition – collection Bouquins)

Colette did however take issue with the second half of the fourth volume of In Search of Lost Time, Sodom and Gomorrah. In her 1932 book, Le Pur et L’impur, which Colette wrote was, “the nearest I shall ever come to writing an autobiography,” …Proust appears in the first line of the chapter called Sodom. “Ever since Proust shed light on Sodom, we have had a feeling of respect for what he wrote, and would never dare, after him, to touch the subject of these hounded creatures, who are careful to blur their tracks and to propagate at every step their personal cloud, like a cuttlefish.

But- was he misled, or was he ignorant?- when he assembles a Gomorrah of inscrutable and depraved young girls, when he denounces an entente, a collectivity, a frenzy of bad angels, we are only diverted, indulgent, and a little bored, having lost the support of the dazzling light of truth that guides us through Sodom. This is because, with all due deference to the imagination or the error of Marcel Proust, there is no such thing as Gomorrah.”

It was Colette who wrote about women’s lives and female desire, because she knew it, because she lived it.

Proust and Colette had completely different writing styles. Her sentences are short, vibrant and lively. His are long, intricate and winding. But they have this in common: their interest in sensation rather than intellect. They both wrote what is now called Autofiction, a combination of autobiography and fiction. They are in their books, sometimes only lightly disguised. The characters around them are sometimes fictional and sometimes people they knew, also lightly disguised. At the end of his lecture, Professor Compagnon said that Proust was destined to write only one book. Colette who lived 30 years longer than Proust wrote many. She had a lifetime of different lives, all of which she recounted in her inimitable auto-fiction way. The Colette exhibition at the BnF is on through mid-January. If you’re in Paris now, you should definitely try to see it. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Thanks to everyone who has been leaving Comments, they are much, much appreciated

New comments on Handel’s Messiah: an uplifting and cautionary tale:

I learn something new every time I read one of your posts. I will be looking for your next “edition”on my Birthday! Happy, healthy New Year. Deedee, Baltimore

Hi Dr. B, so glad that I caught up with this post of yours. December is a favourite month of the year for me because I love all that festivity baking, cooking, family gathering, AND singing. Two years ago I sang Handel's Messiah with Queensland Choir and that was just so magical. For me, singing is better than exercise; it's both body and mind. Every two years Queensland Choir invites members of the public to sing with them (I am a member of the public; I love singing but I'm not very good at music). I am not religious but Handel's Messiah is very special. Shiao-Ping, Brisbane, Australia

I read and recommend Charles King's Every Valley, a rich contextual history of the making of the Messiah and a good exposition of Handel's career, in Germany and then England. And even at Trinity Church Wall Street's annual Messiahs (available on YouTube) there are always a few people who start to slip out of the pews after the Hallelujah chorus, wondering no doubt what's wrong with the rest of us. Bonne année from Maribeth, Brooklyn.

New comments on The Remembered Soldier:

Beverly, your review is a real declaration of love to the reading. It is an invitation to unplug to better connect to the essentials. It is rare that a criticism is itself a literary text. Thank you for this masterstroke. A real treat!! Gerard, Versailles

Hi Beverly, great review, i also loved this book. One of her other books is - i think - even better. In English the title is The song of the stork and the Dromedary. It is an amazing play on the Bronte sisters and their work. Breathtaking. Pieter, Amsterdam

Dear Beverly, Thank you for the lovely tribute to The Remembered Soldier. Delighted to learn how you savored this amazing novel. All the best, Michael Michael Z. Wise, Publisher New Vessel Press

New comment on Giovanni Boldini: The Master of Swish:

What beautiful women’s gowns, what lush colours and all. How different were they from the Jazz Age women’s dresses in the 1920s across the Atlantic! Women’s clothing has come a long way. I read that in the animal kingdom it is often the males who take the lead in wooing the opposite sex; humans, on the other hand, have traditionally had a different script. Thanks for all your write-ups - they are a treat to read over the holiday season! Shiao-Ping, Brisbane, Australia

New comment on Projet Proust: Or how I became a Proust-head:

It’s a dream to be able to read the French version of À la recherche du temps perdu. I imagine you would feel closer to Proust to read his books in French. The Greenwich-based Zoom book club that I belong to, reads about 120-130 pages every month and it takes 2 and a half years to complete all seven volumes. A new round will begin in July 2026. Shiao-Ping, Brisbane, Australia