Les Parisiennes et les Parisiens d'antan

People of Paris 1926-1936, Musée Carnevalet

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. There were a few exhibitions in Paris that I saw just before I left that I haven’t had time to tell you about, busy as I was with telling you about so many others! Among those exhibitions was one on the painter Greuze, another on the painter Jacques Louis David and one at the Musée Carnevalet, on the Censuses of 1926, 1931 and 1936.

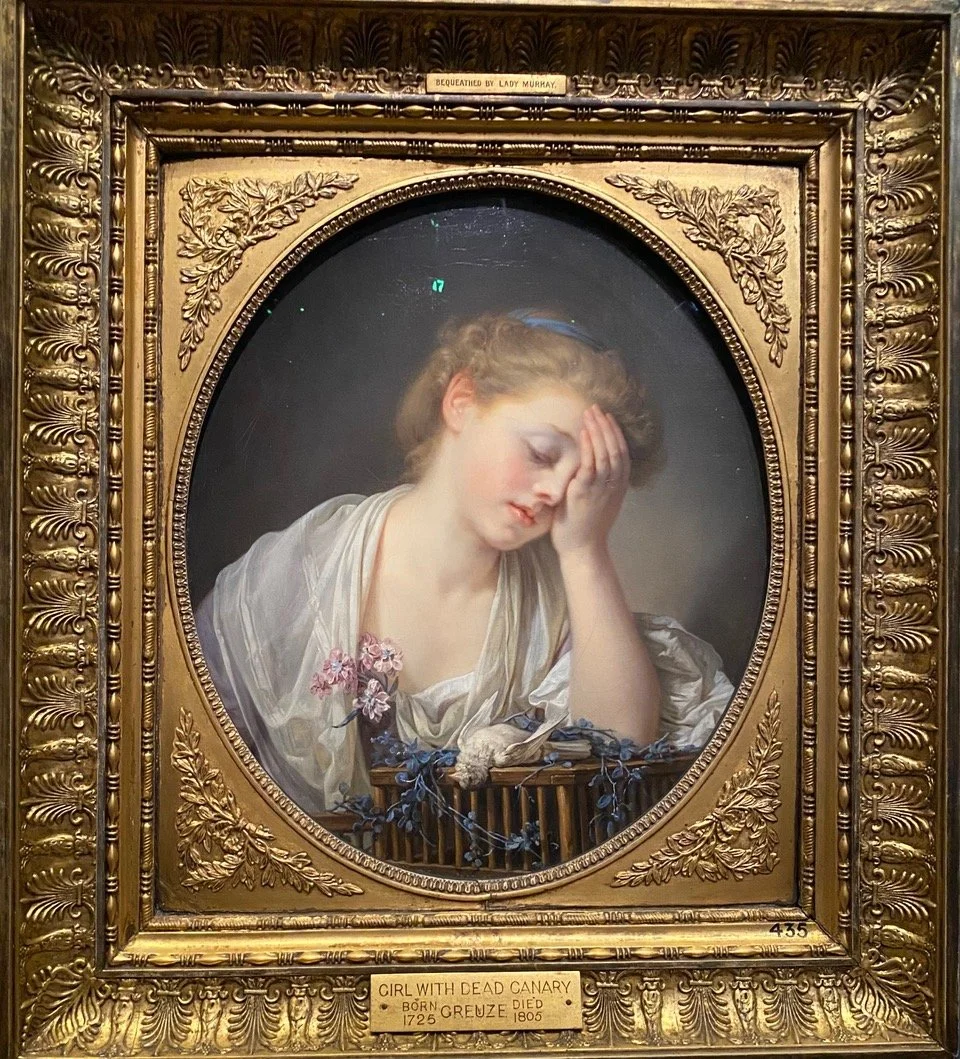

The exhibition on Greuze, called Childhood was the sort of art history exhibition that fans of Greuze in particular and 18th century French painting in general, would love. But it wasn’t all pretty pictures. It considered the paintings we associate with Greuze in the context of 18th century Enlightenment views about the importance of childhood. Greuze’s work is generally associated with paintings of young girls, sometimes sad, sometimes contemplative, usually mourning the death or escape of a bird or the mess that dropped eggs or spilled milk has created. All of these images are euphemisms for lost virginity. There were a lot of those paintings here, but there were other images, too, of happy mothers and smiling toddlers, respectful sons and ungrateful ones. All show childhood as a distinct moment in life and the joys of being a loving mother. (Figs 1-3)

Figure 1. Girl with Dead Canary, J.B. Greuze

Figure 2. Happy Mother, J.B. Greuze

Figure 3. Ungrateful Son Leaves Family, J.B. Greuze

The exhibition also discusses Greuze’s attempt to join the French Academy of Painters as a history painter, the most prestigious category of painting. To become a member, an artist submitted a painting, called a ‘reception piece.’ Greuze knew what he wanted to submit but he kept dragging his feet. Finally, after 13 years, Greuze presented ‘Septimius Severus and Caracalla’. A subject taken from ancient history. But his attempt to gain recognition as a history painter failed. The Academy accepted him as a member, but as a genre painter, a category only marginally more prestigious than flower painter. To make the sting worse, the Academy declared that Septimius Severus was a painting "of the greatest mediocrity". (Fig 4) As the curators note, “with this judgement, they refused to acknowledge the painting's pioneering aesthetic,” that it foreshadowed the neoclassical art of Jacques-Louis David, that it’s moralizing story was meant “as a criticism against princes who put their personal interests over those of the nation.” Humiliated, Greuze stopped showing his work at the Salons. He exhibited his paintings in his own studio. He was successful for a very long time, until that is, taste changed. (Fig 5)

Figure 4. Septimius Severus and Caracalla, J.B. Greuze, 1769

Figure 5. Another young girl, another dead bird, J.B. Greuze

Greuze, was, according to the curators “an audacious, free-spirited figure.” His wife, Anne-Gabrielle Babuty was, too. At the turn of the 1780s, when Greuze was in his 50s, when his work had fallen out of favor, his relationship with his wife reached the breaking point. Greuze accused her of embezzling money he made from the sale of engravings after his work. He accused her of cheating on him with multiple lovers. He accused her of neglecting their daughters's education. We don’t know in what ways she found him lacking, but we do know that they separated in 1785 and divorced in 1793. Twelve years later (1805), he died, poor and forgotten but with his daughters close by.

An exhibition at the Louvre was another first rate review of the work and times of an important French artist of the 18th/19th century - Jacques-Louis David. What a relief to be at a relatively empty exhibition - so unlike the Jacquemart-André where one can barely move in the cramped spaces filled with visitors and their guides. Or the John Singer Sargent exhibition that was also crammed full of people the day we were there. But alas, what could have been a delight was a disaster. A mother with a screaming child who careened dangerously close to the huge paintings. A child who could not be controlled by any of the three adults she was with (mother, grandmother, nanny). The guards did nothing. They were probably afraid to be labelled anti-family or worse. If I was more confident of my French, I would have told the mother that her inability to rein in her toddler was ruining the experience for her and for all of us. But I didn’t. The exhibition was a wonderful survey of David’s work, from Neoclassical paintings to paintings for the French Revolution and then for Napoleon. And portraits painted during his banishment from France. His life, in art and politics, was very well documented. (Figs 6-8)

Figure 6. Belisarius Begging for Alms, J. L. David

Figure 7. Oath of the Tennis Court, J.L. David

Figure 8. Napoleon at St. Bernard’s Pass, J.L. David

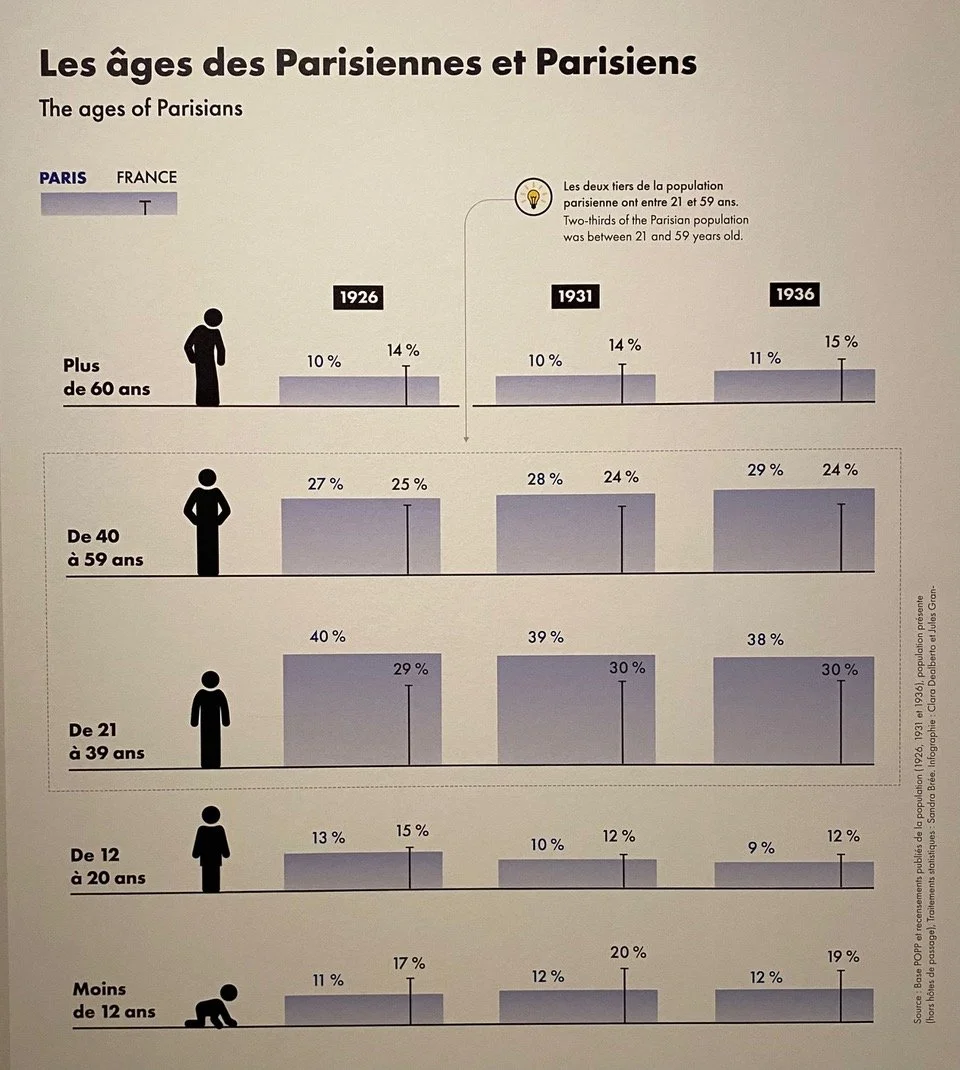

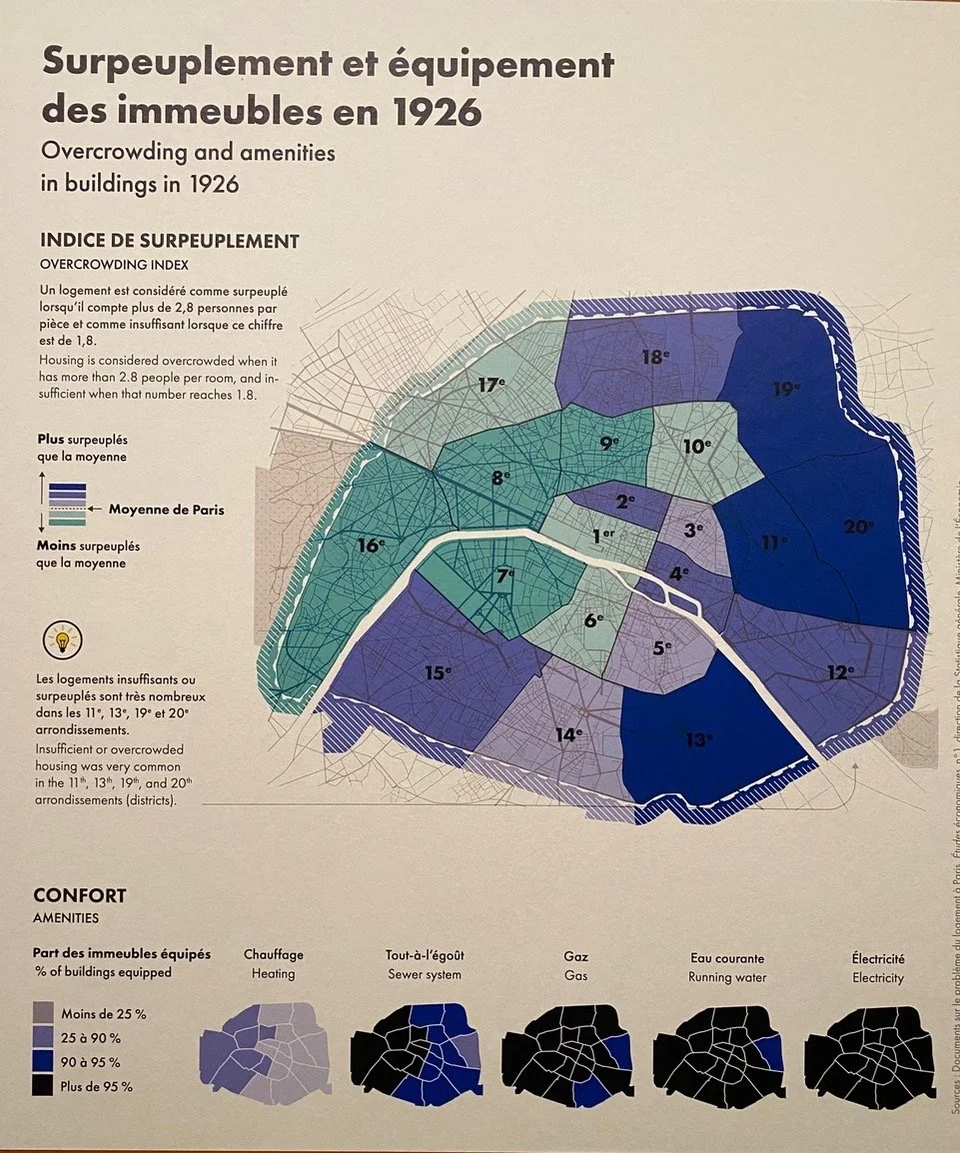

Last week, I discussed an exhibition organized around a single subject for which the curators’ task was to find examples and then organize those examples into categories, themes. This exhibition, Les gens de Paris 1926-1936, at the Carnevalet, has, as its subject, the Censuses of 1926, 1931 and 1936. Lots of categories for the curators to work with: names and surnames, years of birth, places of birth, citizenship, marital status and professions of every individual living in Paris on the day each census was taken. The curators task here was to find compelling stories and tell them through images and objects, augmented, of course, by charts and graphs. (Figs 9, 10)

Figure 9. Ages of Parisians in 1926, 1931, 1936

Figure 10. Apartment buildings, too many people, too few amenities, 1926

The exhibition has an interactive component. If you have ancestors who lived in Paris a century ago or you’re curious about a famous person who was in Paris in 1926 or 1931 or 1936, or if you live or rent a place in Paris that is at least 90 years old, you can learn about them, at the exhibition and online. Because the census registers have been digitized and can be searched, thanks to an historical demographic database created with the help of new Al tools. All you need is a surname or an address.

During the interwar years, Paris was densely populated.There were lots of young adults, although because of the First World War, there were fewer men than women. And there weren’t a lot of children or older people, either. What kept the population high was the number of people who emigrated to the city. People from all over France and Algeria, from France’s colonies and protectorates and from foreign countries, too. Something that we should all be keeping in mind as so many people’s lives unravel around us.

The exhibition walls are filled with paintings and photographs of people, some famous, some not so famous, some not famous at all, but all of whom had one thing in common, they lived in Paris at some time between 1926 and 1936. I recognized plenty of the people, their names and faces have popped up in exhibitions about them and/or others. Like Natalie Clifford Barney and Josephine Baker (Colette exhibition), Suzi Solidor (Tamara Lempicka exhibition), Kiki de Montparnasse (exhibition on Man Ray) and Gertrude Stein (exhibition on Stein and Picasso). And many others, too. (Figs 11-14)

Figure 11. Paintings of people who lived in Paris during the first third of 20th century

Figure 12. Top, Natalie Clifford Barney by Romaine Brooks (left), Suzi Solidor (right) by Pierre Sichel

Figure 13. Josephine Baker, Limot

Figure 14. Kiki de Montparnasse with a few friends, Brassai

There was a documentary from 1926, called Voici, produced when documentaries were growing in popularity and Paris was becoming an open-air movie set. The film was like strolling through Paris, from the busy streets of the Grands Boulevards to the well manicured Tuileries Gardens and the dignified Avenue du Bois. We learned about the daily newspapers that proliferated. And from 1931 on, the screening rooms called ‘Cinéac,’ which showed newsreel footage. All of which led to a 1935 law recognizing the profession of journalist.

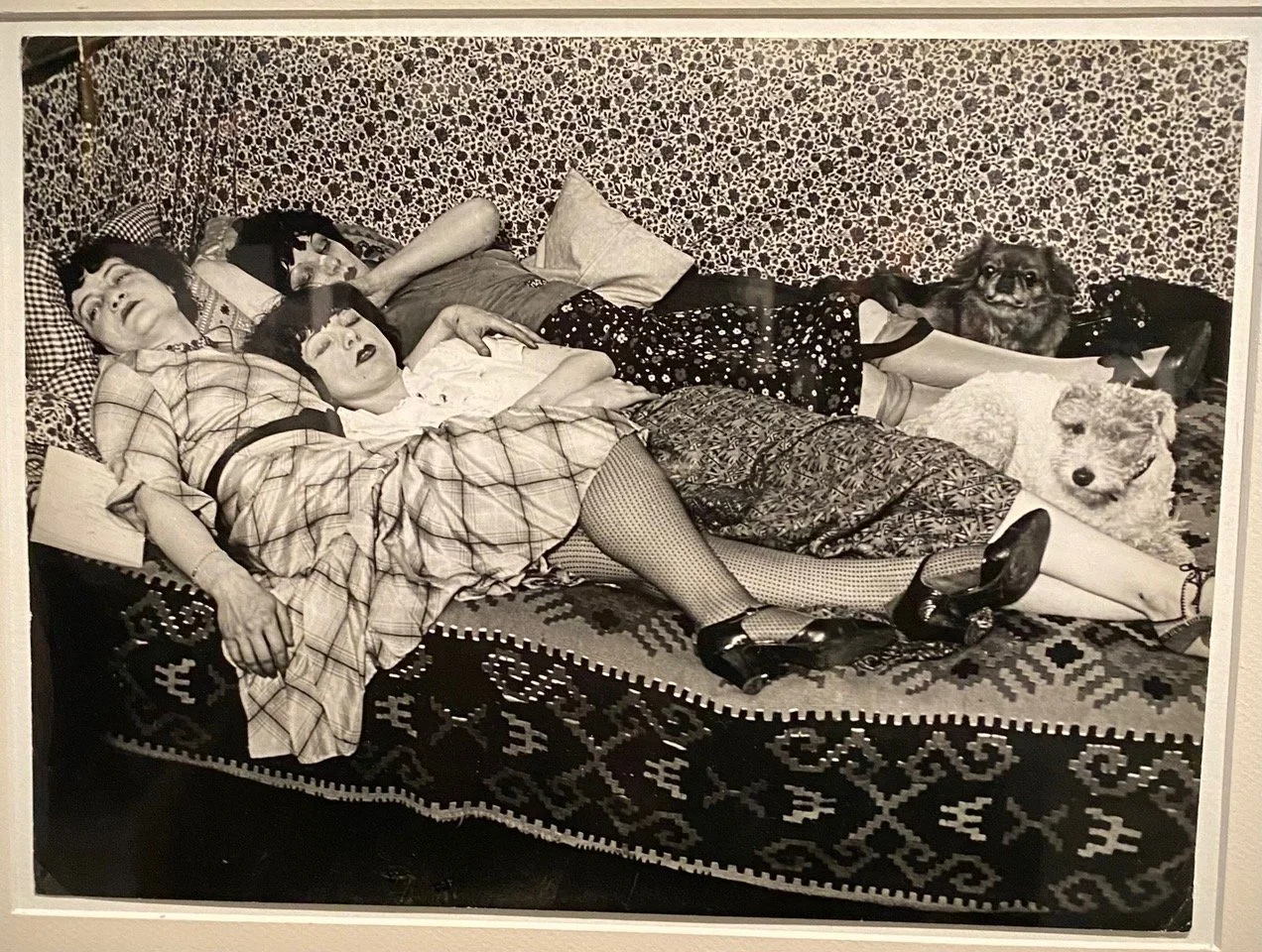

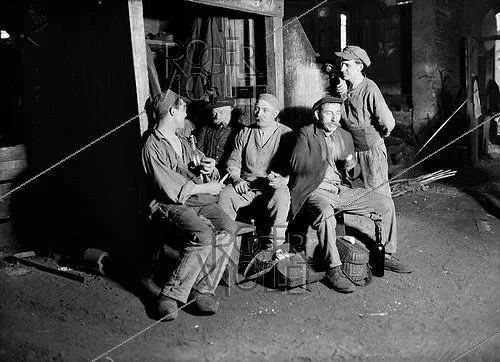

Magazines were much in evidence at the exhibition because they were filled with photographs - it was the beginning of photojournalism. Photos included those by some of the greatest photographers of the time, among them three Hungarians, André Kertész, Brassai (Fig 14) and François Kollar, whose photographs in ‘France Works’ (1931 - 1934) “established (him) as one of the greatest industrial reporters of the time.” (Figs 15, 16)

Figure 15. Eiffel Tower, André Kertész

Figure 16. Iron Industry Workers, François Kollar

Using the data supplied by the censuses, the curators investigated the stereotype of Paris as the "City of Love.” Paris got that title, according to the curators, because nearly 30% of the people over 15 living in Paris were single. They were in Paris because they needed a job. But they were also there to enjoy life - which they did in dance halls, at balls and in salons. Day and night, “crowds flocked to the many venues in Pigalle and Montparnasse, where musicians and music hall stars, like Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, or Suzy Delair, performed.”

The exhibition taught me about a tradition and a nickname for fashionable young women. The tradition, Catherinettes, stems from the middle ages. It began as a way for young, single women to find a husband. Each year, (until they got married) on November 25, the feast day of St. Catherine of Alexandria, the patron saint of unmarried women, they placed a hat on her statue. By 1926, the tradition had metamorphosed. Every November 25, single women who were 25 years old and who worked in the fashion industry, would celebrate by wearing elaborate hats and participating in processions and festive gatherings. The tradition evolved, according to the curators, from a prayer for husbands to a creative display of independence. The term, Midinettes is another reference to young Parisian women, often seamstresses or shopgirls. Midinette is a blend of midi + dinette (light meal). Because these stylish young women were so busy that they only had time for a quick, light lunch at noon. (Figs 16, 17)

Figure 16. Marche of the Catherinettes and one of the dresses worn

Figure 17. Midinette journal

According to the data, lots of men and women lived together without ‘benefit of marriage’ although those who wanted children, eventually did marry. And yet the statistics show that half of the married couples living in Paris had no children. In 1924, the National Alliance for Population Growth, stated, "We need to have more births." French family policies promoted natality and supported large families. Simultaneously penalties for abortion were tightened and information about contraception was banned.

There’s a photo of the Guillemin family who was awarded the Cognacq-Jay Prize in 1936. This prize, created in 1922, was awarded to one family in each department that had at least 9 children. I remember reading about how the childless founders of La Samaritan Department Store supported their employees and their families.

The 1936 census provides details about the prize-winning family: the father, Jules Guillemin, aged 42, was a foundry worker. The mother, Juliette, aged 38, was listed as having no gainful employment. Are you kidding - she was working, she just wasn’t getting paid. They lived with Juliette's mother (thank goodness), and their 9 children. (Fig 18)

Figure 18. Guillemin Family, winner of 1936 Cognacq-Jay Prize

This seems like a good time to talk about work. Over 85% of men aged 15 - 64 worked and 50% of women did too. Although more women may have worked but did not wish to share that information in the census (maybe they or their husbands were ashamed that they needed to work). In 1926, 37% of Parisian men and 30% of Parisian women worked in the industrial sector; 27% of men and 19% of women worked in sales; and 31% of women and 5% of men worked in caregiving. In the 1930s, a variety of things happened that both worsened and ameliorated working people’s situations. The economic crisis of the 1930s, brought mass unemployment. For those lucky enough to have a job in 1936, the legal number of working hours per week dropped from 48 to 40 hours and paid leave was instituted. And the minimum age for children to legally work became 14.

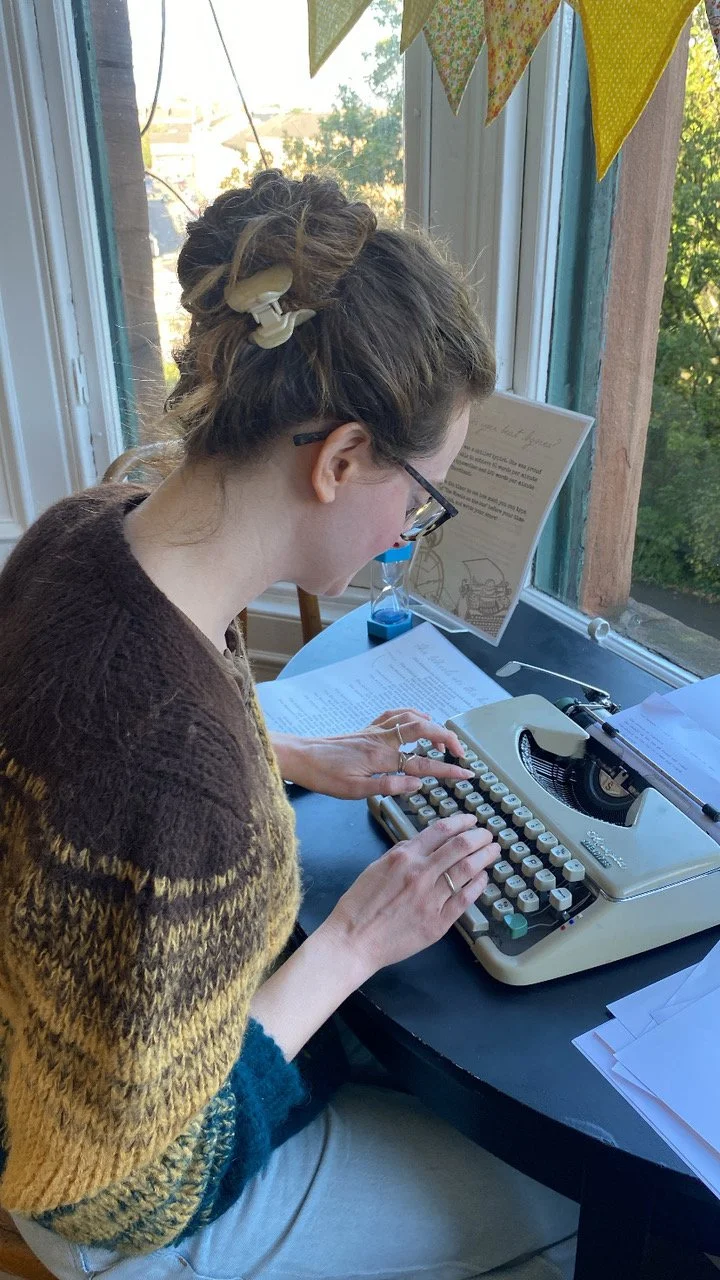

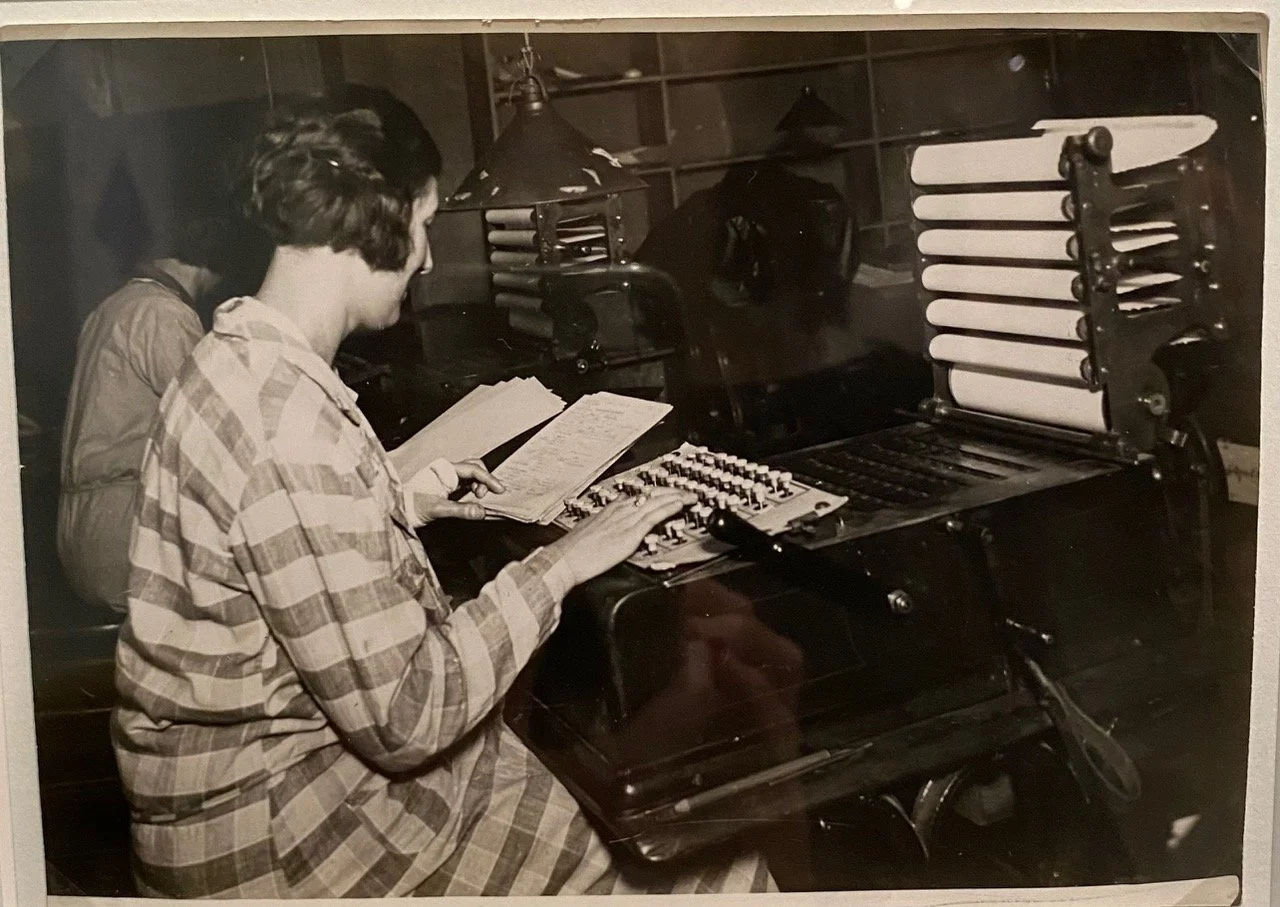

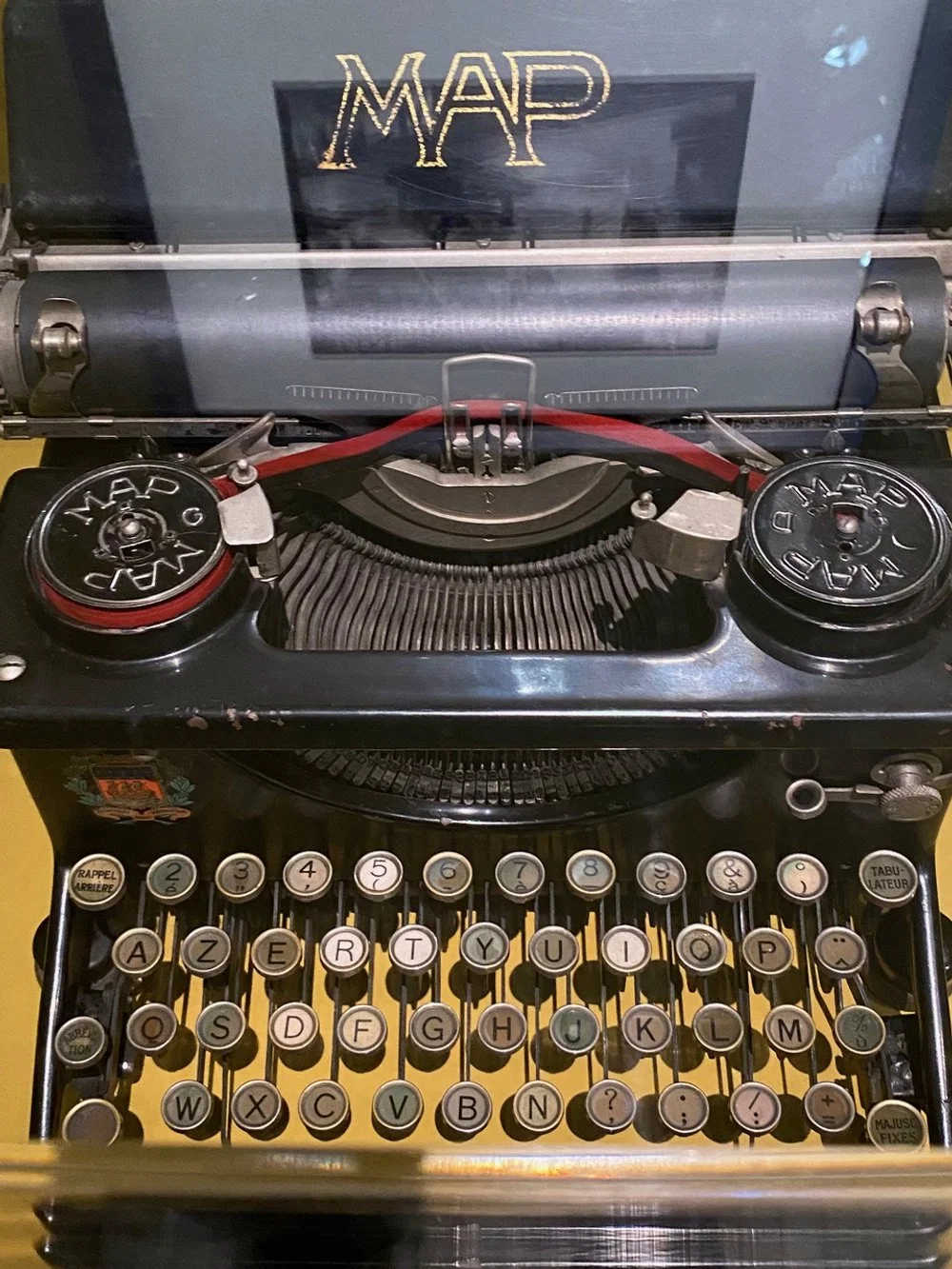

At the Tenement House exhibition in Glasgow this summer, I learned that secretarial work, which had been a male occupation, became one of the most popular jobs for women. Because of the typewriter which was considered best suited for smaller fingers. The curators at this exhibition made the same point as they noted that typists, stenographers and telephone operators came to exemplify the new model of active, salaried women, the archetype of the modern female employee. (Figs 19-21)

Figure 19. Ginevra typing at the Tenement House, Glasgow

Figure 20. Woman tabulating Census statistics

Figure 21. 1920s typewriter

Women were also seamstresses, because of the expansion of haute couture - from 20 fashion houses in 1914 to over 200 in 1929. Of course, most women worked in the domestic sector. The job of concierge (in America the building “Super”) was women’s work during the interwar years. There were roughly 52,000 concierges. According to the curators, their salaries were low and they relied on tips and holiday bonuses to get by. And also I’m guessing then as now, their lodgings (ground floor loges) were included.

There was lots of information about overpopulation and abandoned children and homelessness and health and sanitation. Many buildings were outdated, unsanitary, or, in the case of slums, unlivable. An area would be declared uninhabitable if there was a high number of tuberculosis-related deaths in the building. When 17 blocks were classified as unlivable and the buildings marked for demolition, tenants were evicted. But they had nowhere to go. To address problems like these, affordable housing was built for both poor and middle class people. Yet even many apartment buildings that were not condemned had no sanitation facilities, so neighborhood public bath houses were opened. (Fig 22)

Figure 22. Public Bath, Baubourg Bain-douch St. Merri, 4ieme arrondissement

Furnished hotels were popular places for people who came to Paris in search of work. One furnished hotel that was inspected in 1934, was home to about 100 laborers. Rooms for 4 people were between 10 to 15 square meters (sqm) in size. Dormitory rooms were double that size, with 9 beds. The few single rooms were about 5 sqm. For 100 men, there was one water supply point and 4 toilets.

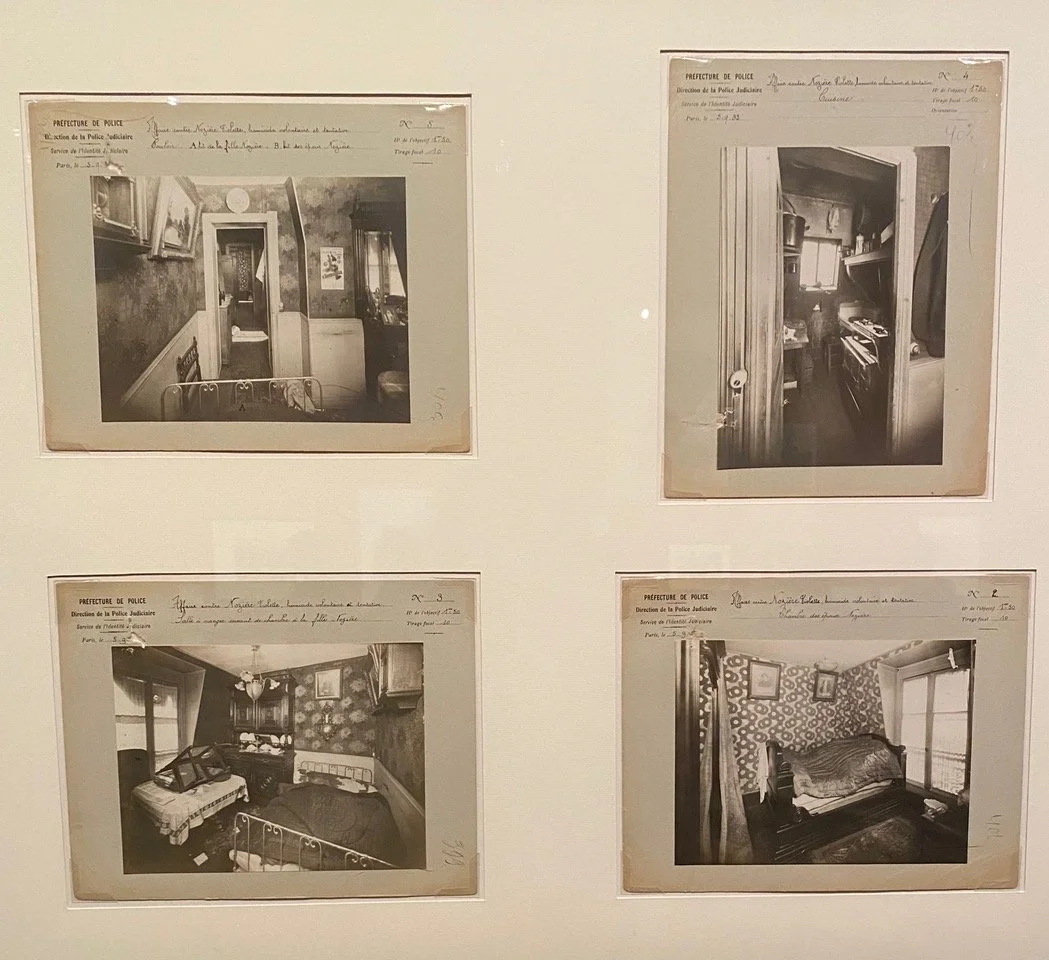

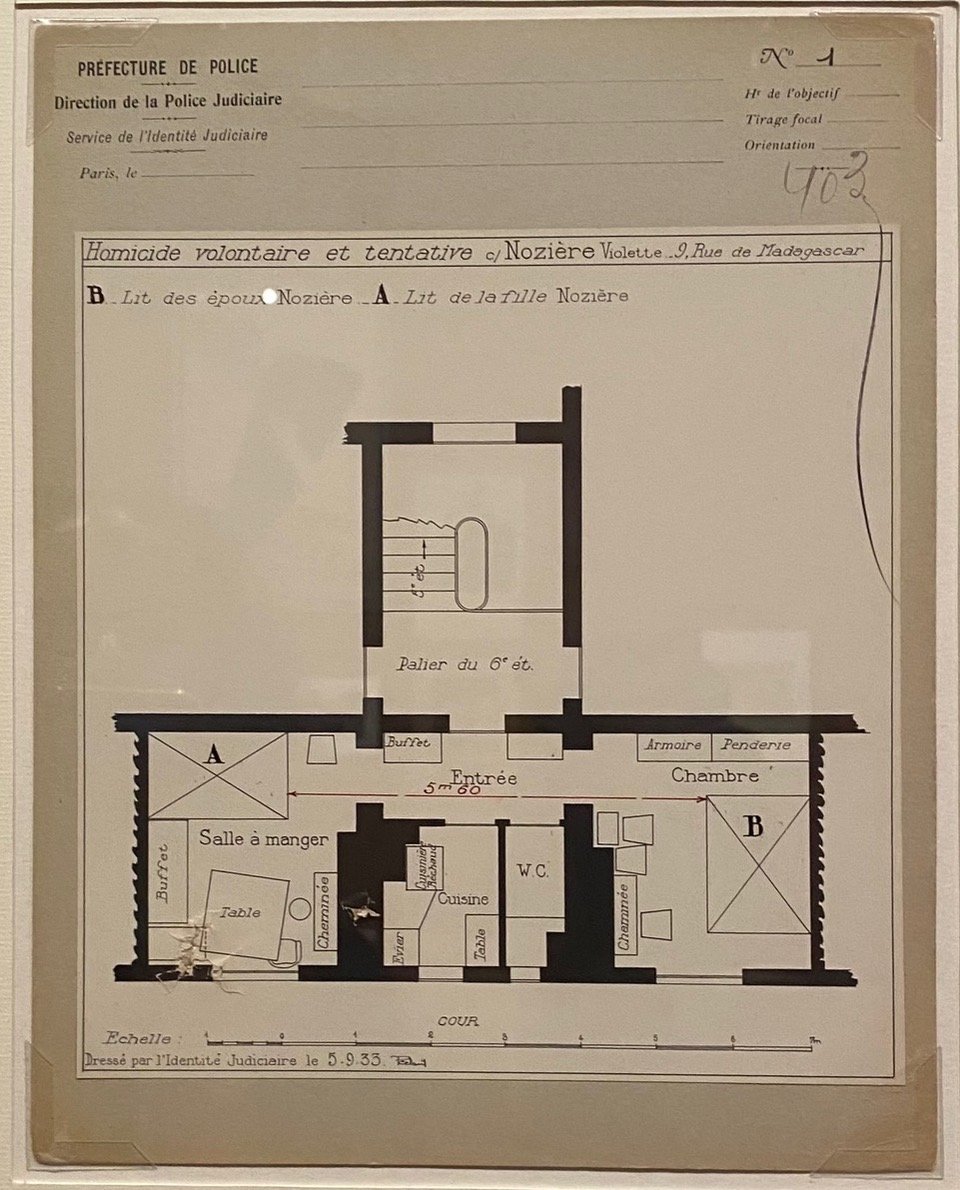

I have already mentioned the Tenement House exhibition in Glasgow in connection with the feminization of secretarial work. I was reminded of it again when I read about the Violette Nozière case. In Glasgow I learned how a middle class person lived during the first half of the 20th century because I could wander around the unchanged apartment of a middle class person. The way I learned about how a middle class family lived in Paris at about the same time was because of a crime that was committed in a middle class apartment and the photographs that were taken of that apartment.

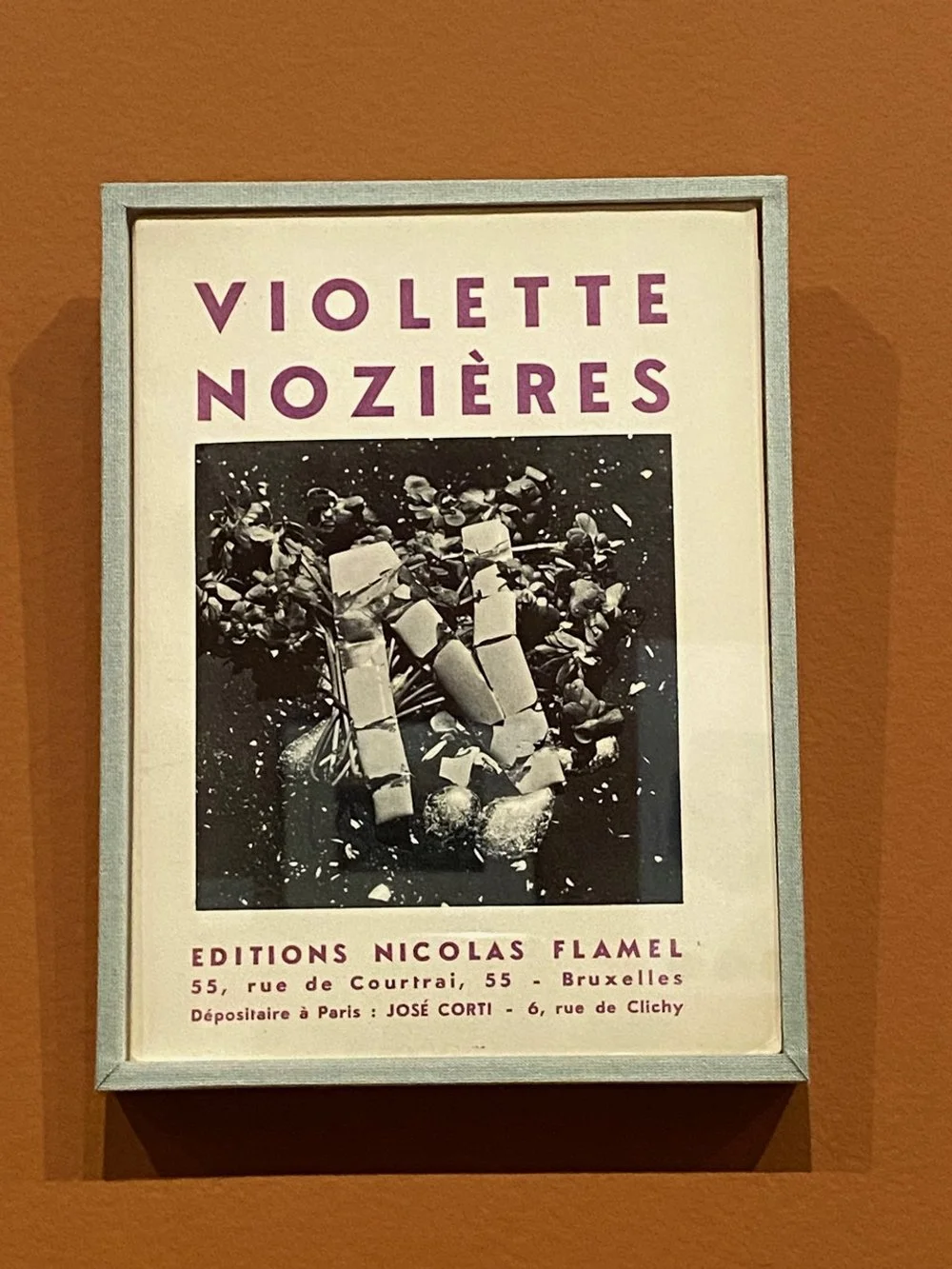

Here’s what happened, on 21 August 1933, Violette Nozière poisoned her parents in their home at number 9, Rue de Madagascar, in the 12th arrondissement. The mother, survived, the father, died. The story of Violette Nozière, aged 18 in 1933, combined two taboos: parricide and incest. Violette Nozière explained that she had resorted to killing her parents because her father was raping her and presumably her mother was doing nothing to help her daughter. Rather than feeling sympathy for her plight, popular opinion and the law turned against Violette. What she suffered had, according to the curators, “exacerbated the heinousness of her actions in the eyes of her contemporaries.” She was sentenced to death. Her sentence was commuted to hard labor for life. After 12 years, she was released. Among the documents from the crime are photographs of the apartment in which this family lived. It was a one-bedroom flat, cramped but comfortable, with gas, water and separate toilet, meant for couples with only one child. It was about the same size as the middle class apartment in Glasgow at the same time. (Figs 23-26)

Figure 23. Photograph of Violette Nozière

Figure 24, Rooms in the Nozière apartment

Figure 25. Floor Plan of Nozière apartment

Figure 26. Book about the Violette Nozière patricide

One final image at the exhibition dealt with the social realities of the 1930s. It was a reproduction of a mural that was created for the 1936 Household Arts Fair, by interior designer and architect Charlotte Perriand. At the fair, she exhibited a living room she had designed for an HBM (Habitation à Bon Marché low-cost housing). “As a committed theorist of the art of living, she coupled this interior design with a critique of urban squalor in the form of a monumental photomontage: The Great Misery of Paris.” (Fig 27) Photos and drawings reference unemployment - people stand in line waiting for money, people stand in line waiting for food. The plight of unmarried foreigners looking for work was highlighted. Upon arrival, they were sent back to their home countries. And so it goes. See this exhibition if you can, you’ll be glad you did! Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 27. The Great Misery of Paris (detail) Charlotte Perriand, 1936

Thanks for the Comments on Empire of Sleep, they were much appreciated.

New comment on The Empire of Sleep:

What a fascinating theme to explore through art! Roughly 20 years ago I was on my own in London, and stumbled on the Wellcome Collection, a museum of health and medical objects inspired by the collection of Henry Wellcome. At the time they had a wonderful exhibition on sleep, exploring the topic through objects, art, videos, etc.Sleep/Welcome Collection https://share.google/Kh0bb5tSwVx8r01l4, It was very thought-provoking: what are the lines between sleep, comas, and death? What is the actual difference between consciousness and unconsciousness? What actually HAPPENS during sleep? What happens when you do not sleep? Thank you for sharing these beautiful images; you have triggered fond memories and expanded my understanding! --Bonnie in Rhinebeck, NY

Hi Beverly, I’ve been out of touch for quite a while but this last article you wrote is really terrific for me particularly since I don’t see so good anymore. it allows me to enjoy an exhibition that otherwise I probably could not go to or at least wouldn’t enjoy because when they’re crowded , ill-lit and I can’t get close enough — actually I can never read the labels no matter how close I am — but I can’t get close enough to really look at the pictures either, when you write about it , I can just enlarge the pictures on my screen and enjoy your comments about them. so thanks again. Another good job Julia, Valluris, FR

This is a great article providing even more context for a wonderful exhibition. Reading this I was reminded of two other depictions of sleep, one I saw recently at the de Young Museum for the Manga exhibit where the graphics follow a man trying to sleep who counts sheep and then the sheep trying to sleep who count him. The other is a piece I saw at the National Portrait Gallery in London many years ago but which made a lasting impression: it a portrait by the great Artist/Photographer Sam Taylor-Johnson of David Beckham --- sleeping! It is a black and white video of the great footballer taking a snooze and remains one of my favorite portraits to this day. I enjoyed reading this to remind me of the exhibit and other works of art that float about in my mind. xx, Ginevra Artist/Designer/Napper, San Francisco

New Comments on Colette:

A little late thanking you for the piece about Colette. Am now 2/3 through The Vagabond, the first piece I have ever read by her. A lifetime ago I designed and built costumes for professional theatres, and although my experience is absolutely nothing like working the musical halls in Paris, I find her tale mesmerizing. I keep needing to stop reading and do something else but just keep reading. I may have to try reading the story in French.

Thank you for opening yet another window! Cheers and all the best for 2026. Peg